Critical Success Factors for Implementation of Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Change at Universities. Volume

Frank Schröder (Hg.) Schröder Frank Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde 4 Higher Education in Africa and Southeast Asia Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde SUPPORTED BY Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences, 2019 Terms of use: Postfach 1940, 49009 Osnabrück This document is made available under a CC BY Licence (Attribution). For more Information see: www.hs-osnabrueck.de https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 www.international-deans-course.org [email protected] Concept: wbv Media GmbH & Co. KG, Bielefeld wbv.de Printed in Germany Cover: istockphoto/Pavel_R Order number: 6004703 ISBN: 978-3-7639-6033-0 (Print) DOI: 10.3278/6004703w Inhalt Preface ............................................................. 7 Marc Wilde and Tobias Wolf Innovative, Dynamic and Cooperative – 10 years of the International Deans’ Course Africa/Southeast Asia .......................................... 9 Bassey E. Antia The International Deans’ Course (Africa): Responding to the Challenges and Opportunities of Expansion in the African University Landscape ............. 17 Bello Mukhtar Developing a Research Management Strategy for the Faculty of Engineering, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria ................................. 31 Johnny Ogunji Developing Sustainable Research Structure and Culture in Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike Ebonyi State Nigeria ....................... 47 Joseph Sungau A Strategy to Promote Research and Consultancy Assignments in the Faculty .. 59 Enitome Bafor Introduction of an annual research day program in the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Nigeria ........................................... 79 Gratien G. Atindogbe Research management in Cameroon Higher Education: Data sharing and reuse as an asset to quality assurance ................................... -

BFA Recipient Organizations in Africa by Country

BFA Recipient Organizations in Africa by Country Algeria University d’Oran Angola Save the Children Botswana BA ISAGO University College Golden Sun Services Botswana Book Project Cameroon ASEC-NW Cameroon Association of Journalists National Book Development Council The Presbytery of St. Andrew Cape Verde American Embassy of Cape Verde Chad United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees/Chad Congo Association AZUR Developpement Eritrea ACORD Asmara University Eritrian Relief Committee Ethiopia Abay Health College Addis Ababa College of Technology and Commerce Admas University College Amhara Development Association American Embassy Association For Children & Youth Cheha Wudma Devlopment Association CODE-Ethiopia Episcopal Conference Ethiopia Knowledge & Technology Transfer Society (EKTTS) Ethiopian Library & Information Foundation For Education Ethiopian Community Development Council Ethiopia Reads Horn Aid UK NIGAT Rotary Club of Addis Ababa SOS Children’s Fund The Gimbie SDA School The Love for Children Organization The Relief Society of Tigray Tigray Development Association YMCA-Ethiopia The Gambia Ministry of Education Rotary Club of Fajara United Kingdom’s Medical Reasearch Council Laboratories YMCA-The Gambia Ghana Action Child Mobilization Assasan Community Schools BRIDGE, Inc. Ghana Book Trust Ghana Institute of Engineers Ghana Institute of Linguistics Kpamba Scholarship Foundation Michael Lapsley Foundation Musab Aid Organization Namalteng Integrated Development Programme Peace Corps-Ghana Prometra Ghana Regent University College -

Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: a Webometric Study

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2020 Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study Samuel Oluranti Oladipupo Mr University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Oladipupo, Samuel Oluranti Mr, "Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study" (2020). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 4549. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4549 Evaluation of Nigeria Universities Websites Using Alexa Internet Tool: A Webometric Study Samuel Oluranti, Oladipupo1 Africa Regional Centre for Information Science, University of Ibadan, Nigeria E-mail:[email protected] Abstract This paper seeks to evaluate the Nigeria Universities websites using the most well-known tool for evaluating websites “Alexa Internet” a subsidiary company of Amazon.com which provides commercial web traffic data. The present study has been done by using webometric methods. The top 20 Nigeria Universities websites were taken for assessment. Each University website was searched in Alexa databank and relevant data including links, pages viewed, speed, bounce percentage, time on site, search percentage, traffic rank, and percentage of Nigerian/foreign users were collected and these data were tabulated and analysed using Microsoft Excel worksheet. The results of this study reveal that Adekunle Ajasin University has the highest number of links and Ladoke Akintola University of Technology with the highest number of average pages viewed by users per day. Covenant University has the highest traffic rank in Nigeria while University of Lagos has the highest traffic rank globally. -

Consortium of Universities for Global Health Annual Report 2017-2019

Consortium of Universities for Global Health Annual Report 2017-2019 (Courtesy of UK Department for International Development) 1608 Rhode Island Ave., Suite 240 Washington, DC 20036 Page 1 Letter from the Chair of the Board and the Executive Director Dear Colleague, During these tumultuous times, the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) continues to grow, diversify, and expand its activities. This may reflect global health’s capacity to be the interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral platform needed to address the complex challenges the world faces. Non-communicable diseases, environmental degradation, climate change, new and old infectious diseases, weak governance, technology, inequality and demographic changes pose deep challenges to achieving a sustainable future for all. Over the last two years we secured four important grants which have strengthened our political engagement and training activities. Our committees and working groups continue to convene experts across the global health enterprise to address numerous challenges. We were very pleased to complete our Capacity Building Platform, an online portal which helps to connect institutions in low resource countries with trainers they may be seeking; we also built an open access, crowd sourcing site that connects research questions with researchers; we created new working groups on Planetary Health-One Health-Environmental Health; Palliative Care; Equity; and Humanities; and we collaborated with our members to hold global health events outside the US (our first was with American University in Beirut). Significantly, we changed our mission statement to reflect our collective efforts to improve the health of people and the planet. Our membership continues to grow, with new members joining CUGH from every region of the world. -

Saharan Africa? a Bibliometric Analysis

Published in: Learned Publishing, v24, n4, October 2011, pp.287-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1087/20110406 Do discounted journal access programs help researchers in sub-Saharan Africa? A bibliometric analysis Philip M. Davis, Research Associate, Department of Communication, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 ([email protected]) Published in: Learned Publishing, v24, n4, October 2011, pp.287-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1087/20110406 Published in: Learned Publishing, v24, n4, October 2011, pp.287-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1087/20110406 Abstract Prior research has suggested that providing free and discounted access to the scientific literature to researchers in low-income countries increases article production and citation. Using traditional bibliometric indicators for institutions in sub-Saharan Africa, we analyze whether institutional access to TEEAL (a digital collection of journal articles in agriculture and allied subjects) increases: 1) article production; 2) reference length; and 3) number of citations to journals included in the TEEAL collection. Our analysis is based on nearly 20,000 articles—containing half a million references—published between 1988 and 2009 at 70 institutions in 11 African countries. We report that access to TEEAL does not appear to result in higher article production, although it does lead to longer reference lists (an additional 2.6 references per paper) and a greater frequency of citations to TEEAL journals (an additional 0.4 references per paper), compared to non-subscribing institutions. We discuss how traditional bibliometric indicators may not provide a full picture of the effectiveness of free and discounted literature programs. Keywords: sub-Saharan Africa, libraries, information transfer, citation analysis Published in: Learned Publishing, v24, n4, October 2011, pp.287-298. -

Management of Records in University Libraries in the South-South Zone of Nigeria

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 12-2011 Management of Records in University Libraries in the South-South Zone of Nigeria Blessing Amina Akporhonor Delta State University Library , Abraka, Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Akporhonor, Blessing Amina, "Management of Records in University Libraries in the South-South Zone of Nigeria" (2011). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 671. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/671 http://unllib.unl.edu/LPP/ Library Philosophy and Practice 2011 ISSN 1522-0222 Management of Records in University Libraries in the South-South Zone of Nigeria Akporhonor Blessings Amina Department of Library and Information Science Delta State University Abraka, Delta State, Nigeria Introduction Universities the world over are centres for academic pursuits as well as place where learning is sought at its maximum level. A university library, be it federal or state owned, is part of a university set up. Accordingly, it seeks to advance the functions of the institution (Kumar, 1987) by generating and transacting information in form of records for teaching, learning, research and for administration in the course of its daily activities (Akporhonor and Iwhiwhu, 2007). In other words, records are created and used in the operation of a university and its library. For a university library to function effectively and carry on with its services, there are usually one form of record or the other. Records are synonymous with human activities and have existed for centuries (Esse, 2000). -

Provision of Security Facilities and Security Personnel Service Delivery in Universities in Cross River State, Nigeria

International Education Studies; Vol. 13, No. 5; 2020 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Provision of Security Facilities and Security Personnel Service Delivery in Universities in Cross River State, Nigeria Comfort R. Etor1, Eno Etudor-Eyo2 & Godfrey E. Ukpabio1 1 Department of Educational Administration and Planning, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria 2 Department of Curriculum Studies and Educational Management, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria Correspondence: Eno Etudor-Eyo, Department of Curriculum Studies and Educational Management, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria. Received: November 9, 2019 Accepted: December 22, 2019 Online Published: April 18, 2020 doi:10.5539/ies.v13n5p125 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v13n5p125 Abstract The study examined provision of security facilities and security personnel service delivery in Universities in Cross River State, Nigeria. Three research questions and one hypothesis guided the study. The ex-post facto design was adopted for the study. The population of the study comprised 440 security personnel while the sample size was 400 security personnel. Two researchers developed and validated instruments entitled “Provision of Facilities Questionnaire (POFQ) and Security Personnel Service Delivery Questionnaire (SPSDQ) were used for data collection. The reliability estimates of the instrument were determined using Cronbach Alpha Analysis and the coefficients of 0.80 and 0.83 were obtained. Descriptive statistics was used to answer the research questions while Pearson Product Moment Correlation was used to test the hypothesis at 0.05 level of significance. The finding of the study showed that there exist a disparity in the provision of security facilities in the institutions with the minimum provision of 11.10 and maximum of 26.00 facilities by State and Federal Universities respectively. -

List of Reviewers (As Per the Published Articles) Year: 2019

List of Reviewers (as per the published articles) Year: 2019 Asian Food Science Journal ISSN: 2581-7752 2019 - Volume 6 [Issue 1] Molecular Characterisation of Bacteria Isolated from Various Part of Chicken (Gallus gallus domestica) Meat DOI: 10.9734/AFSJ/2019/45411 (1) Slim Smaoui, Centre de Biotechnologie de Sfax, Tunisa. (2) Wafaa Abd El-Ghany Abd El_Ghany, Cairo University, Egypt. (3) Krešimir Mastanjević, University of Osijek, Croatia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27719 Microbiological Quality and Sensory Properties of Tarhanas Produced by Addition Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Sourdough as Starter Culture after Different Fermentation Periods DOI: 10.9734/AFSJ/2019/45492 (1) R. Prabha, Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University, India. (2) Chin-Fa Hwang, Hungkuang University, Taiwan. (3) Rosendo Balois Morales, Universidad Autonoma de Nayarit, Mexico. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27759 Determination of Optimum Processing Conditions for the Proximate Composition and Pasting Characteristics of Flour Made from Parboiled Cassava Chips: A Response Surface Analysis DOI: 10.9734/AFSJ/2019/44825 (1) Idakwoji Precious Adejoh, Kogi State University, Nigeria. (2) Patrícia Matos Scheuer, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil. (3) F. A. Bello, University of Uyo, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27768 Nutritional, Elemental and Amino Acid Profile Analyses of the Seeds of Aspilia africana: A Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS) DOI: 10.9734/AFSJ/2019/45776 (1) Takeshi Nagai, Graduate School of Yamagata University, Japan. (2) Sahore Drogba Alexis, Université Nangui Abrogoua d’Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27792 Physicochemical Properties and Mycological Quality of Wheat Flours Consumed in Calabar, Nigeria DOI: 10.9734/AFSJ/2019/45641 (1) Chibor, Bariwere Samuel, Rivers State University, Nigeria. -

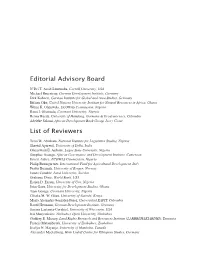

Editorial Advisory Board List of Reviewers

Editorial Advisory Board N’Dri T. Assié-Lumumba, Cornell University, USA Michael Bruentrup, German Development Institute, Germany Dirk Kohnert, German Institute for Global and Area Studies, Germany Effiom Oku, United Nations University Institute for Natural Resources in Africa, Ghana Wumi K. Olayiwola, ECOWAS Commission, Nigeria Ranti I. Olurinola, Covenant University, Nigeria Renny Rueda, University of Hamburg, Germany & Ecodemocracy, Colombia Adeleke Salami, African Development Bank Group, Ivory Coast List of Reviewers Terfa W. Abraham, National Institute for Legislative Studies, Nigeria Sheetal Agarwal, University of Delhi, India Olanrewaju E. Ajiboye, Lagos State University, Nigeria Simplice Asongu, African Governance and Development Institute, Cameroon Ernest Aubee, ECOWAS Commission, Nigeria Philip Baumgartner, International Fund for Agricultural Development, Italy Festus Boamah, University of Bergen, Norway James Conable, Lund University, Sweden Grahame Dixie, World Bank, USA Essien D. Essien, University of Uyo, Nigeria John Gasu, University for Development Studies, Ghana Tayo George, Covenant University, Nigeria Ciliaka M. W. Gitau, University of Nairobi, Kenya Maria Alejandra Gonzalez-Perez, Universidad EAFIT, Colombia Raoul Hermann, German Development Institute, Germany Susana Lastarria-Cornhiel, University of Wisconsin, USA Itai Manyanhaire, Zimbabwe Open University, Zimbabwe Godfrey E. Massay, Land Rights Research and Resources Institute (LARRRI/HAKIARDHI), Tanzania Francis Matambirofa, University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Evelyn -

Innovations in Nigerian Universities: Perspectives of an Insider from a “Fourth Generation” University

www.sciedupress.com/ijhe International Journal of Higher Education Vol. 4, No. 3; 2015 Innovations in Nigerian Universities: Perspectives of An Insider from A “Fourth Generation” University Prof. (Mrs.) Grace Koko Etuk1 1 Department of Curriculum Studies and Educational Management, University of Uyo, P.M.B. 1017, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria Correspondence: Prof. (Mrs.) Grace Koko Etuk, Department of Curriculum Studies and Educational Management, University of Uyo, P.M.B. 1017, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Tel: 234-80-2329-7073. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 5, 2015 Accepted: April 28, 2015 Online Published: August 18, 2015 doi:10.5430/ijhe.v4n3p218 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v4n3p218 Abstract This paper elaborates on innovations which have been effected in universities in Nigeria, using a somewhat young university as a paradigm. The innovations discussed include private ownership of universities, innovative funding strategies and innovative quality assurance practices. These include innovative planning (strategic planning); innovative programme contents; innovations in human and material resources development; innovative admission procedures; innovative carrying-capacity regulations; and innovative programme appraisal procedures and standards. The paper concludes by maintaining that innovation augurs well by improving programme standards and quality of products. Keywords: Innovations, Quality assurance, Strategic planning, Accreditation, Funding, Marketing 1. Introduction Federal universities in Nigeria are often categorized on the basis of the years that they were founded. This gives rise to first, second, third, fourth and so on, generation of Federal universities in Nigeria. Those that were established in the 1960s are often referred to as the first generation universities. -

STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES in AFRICA a Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps

STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES IN AFRICA A Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps JOHN SSEBUWUFU, TERALYNN LUDWICK AND MARGAUX BÉLAND Funded by the Canadian Government through CIDA Canadian International Agence canadienne de Development Agency développement international STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES IN AFRICA: A Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps Prof. John Ssebuwufu Director, Research & Programmes Association of African Universities (AAU) Teralynn Ludwick Research Officer AAU Research and Programmes Department / AUCC Partnership Programmes Margaux Béland Director, Partnership Programmes Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) Currently on secondment to the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE) Strengthening University-Industry Linkages in Africa: A Study of Institutional Capacities and Gaps @ 2012 Association of African Universities (AAU) All rights reserved Printed in Ghana Association of African Universities (AAU) 11 Aviation Road Extension P.O. Box 5744 Accra-North Ghana Tel: +233 (0) 302 774495/761588 Fax: +233 (0) 302 774821 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web site: http://www.aau.org This study was undertaken by the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) as part of the project, Strengthening Higher Education Stakeholder Relations in Africa (SHESRA). The project is generously funded by Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). The views and opinions -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY