Quantification and the Count-Mass Distinction in Mandarin Chinese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi Smriti Singh1, Om P. Damani2, Vaijayanthi M. Sarma2 (1) Insideview Technologies (India) Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad (2) Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We present algorithms for identifying Hindi Noun Groups and Verb Groups in a given text by using morphotactical constraints and sequencing that apply to the constituents of these groups. We provide a detailed repertoire of the grammatical categories and their markers and an account of their arrangement. The main motivation behind this work on word group identification is to improve the Hindi POS Tagger’s performance by including strictly contextual rules. Our experiments show that the introduction of group identification rules results in improved accuracy of the tagger and in the resolution of several POS ambiguities. The analysis and implementation methods discussed here can be applied straightforwardly to other Indian languages. The linguistic features exploited here are drawn from a range of well-understood grammatical features and are not peculiar to Hindi alone. KEYWORDS : POS tagging, chunking, noun group, verb group. Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Papers, pages 2491–2506, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 2491 1 Introduction Chunking (local word grouping) is often employed to reduce the computational effort at the level of parsing by assigning partial structure to a sentence. A typical chunk, as defined by Abney (1994:257) consists of a single content word surrounded by a constellation of function words, matching a fixed template. Chunks, in computational terms are considered the truncated versions of typical phrase-structure grammar phrases that do not include arguments or adjuncts (Grover and Tobin 2006). -

“Sorry We Apologize So Much”

Intercultural Communication Studies VIII-1 1998-9 Chu-hsia Wu [Special phonetic symbols do not appear in the online version] Linguistic Analysis of Chinese Verb Compounds and Measure Words to Cultural Values Chu-hsia Wu National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan Abstract Languages derived from different families show different morphological and syntactic structures, therefore, reflect different flavors in the sense of meaning. Inflections and derivatives do more work in Western languages than is asked of them in Chinese. However, the formation of verb compounds allows Chinese to attain the enlargement of lexicon. On the contrary, measure words do more work in Chinese but there is no exact equivalent of Chinese measure words in English. In this study, the Chinese verb compounds such as verb-object compound, cause-result compound, synonymous, and reduplication to cultural values will be discussed first. Measure Words to Cultural Symbolism will be rendered next from two aspects, pictorial symbolism and the characteristics to distinguish noun homophones. Introduction Languages derived from different families show different morphological and syntactic structures, therefore, reflect different flavors in the sense of meaning. Inflections and derivatives do more work in Western languages than is asked of them in Chinese. However, the formation of verb compounds allows Chinese to attain the enlargement of lexicon. On the contrary, measure words do more work in Chinese but there is no exact equivalent of Chinese measure words in English. Therefore, the purpose of this paper will be focused on the formation of verb compounds and the use of measure words relating to their corresponding meanings in Chinese respectively. -

Tagging Guidelines for BOLT Chinese-English Word Alignment

Tagging Guidelines for BOLT Chinese-English Word Alignment Version 2.0 – 4/10/2014 Linguistic Data Consortium Created by: Xuansong Li, [email protected] With contributions from: Niyu Ge, [email protected] Stephanie Strassel, [email protected] BOLT_TaggingWA_V2.0 Tagging Guidelines for BOLT Chinese-English Word Alignment Page 1 of 24 Version 2.0 –4/10/2014 Table of Content 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 2 Types of links ................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Semantic links ........................................................................................ 4 2.2 Function links .......................................................................................... 4 2.3 DE-clause links ....................................................................................... 5 2.4 DE-modifier links .................................................................................... 6 2.5 DE-possessive links ............................................................................... 6 2.6 Grammatical inference semantic links .................................................... 6 2.7 Grammatical inference function links ...................................................... 7 2.8 Contextual inference link ........................................................................ 7 3 Types of tags ................................................................................................ -

Chinese: Parts of Speech

Chinese: Parts of Speech Candice Chi-Hang Cheung 1. Introduction Whether Chinese has the same parts of speech (or categories) as the Indo-European languages has been the subject of much debate. In particular, while it is generally recognized that Chinese makes a distinction between nouns and verbs, scholars’ opinions differ on the rest of the categories (see Chao 1968, Li and Thompson 1981, Zhu 1982, Xing and Ma 1992, inter alia). These differences in opinion are due partly to the scholars’ different theoretical backgrounds and partly to the use of different terminological conventions. As a result, scholars use different criteria for classifying words and different terminological conventions for labeling the categories. To address the question of whether Chinese possesses the same categories as the Indo-European languages, I will make reference to the familiar categories of the Indo-European languages whenever possible. In this chapter, I offer a comprehensive survey of the major categories in Chinese, aiming to establish the set of categories that are found both in Chinese and in the Indo-European languages, and those that are found only in Chinese. In particular, I examine the characteristic features of the major categories in Chinese and discuss in what ways they are similar to and different from the major categories in the Indo-European languages. Furthermore, I review the factors that contribute to the long-standing debate over the categorial status of adjectives, prepositions and localizers in Chinese. 2. Categories found both in Chinese and in the Indo-European languages This section introduces the categories that are found both in Chinese and in the Indo-European languages: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. -

Classifiers Determiners Yicheng Wu Adams Bodomo

REMARKS AND REPLIES 487 Classifiers ϶ Determiners Yicheng Wu Adams Bodomo Cheng and Sybesma (1999, 2005) argue that classifiers in Chinese are equivalent to a definite article. We argue against this position on empirical grounds, drawing attention to the fact that semantically, syntactically, and functionally, Chinese classifiers are not on the same footing as definite determiners. We also show that compared with Cheng and Sybesma’s ClP analysis of Chinese NPs (in particular, Cantonese NPs, on which their proposal crucially relies), a consistent DP analysis is not only fully justified but strongly supported. Keywords: classifiers, open class, definite determiners, closed class, Mandarin, Cantonese 1 Introduction While it is often proposed that the category DP exists not only in languages with determiners such as English but also in languages without determiners such as Chinese (see, e.g., Pan 1990, Tang 1990a,b, Li 1998, 1999, Cheng and Sybesma 1999, 2005, Simpson 2001, 2005, Simpson and Wu 2002, Wu 2004), there seems to be no consensus about which element (if any) in Chinese is the possible counterpart of a definite determiner like the in English. In their influential 1999 article with special reference to Mandarin and Cantonese, Cheng and Sybesma (hereafter C&S) declare that ‘‘both languages have the equivalent of a definite article, namely, classifiers’’ (p. 522).1 Their treatment of Chinese classifiers as the counterpart of definite determiners is based on the following arguments: (a) both can serve the individualizing/singularizing function; (b) both can serve the deictic function. These arguments and the conclusion drawn from them have been incorporated into C&S 2005, C&S’s latest work on the classifier system in Chinese. -

Mpub10110094.Pdf

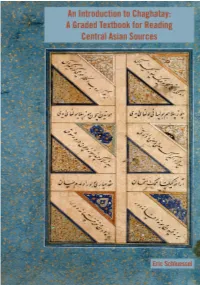

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

Word Segmentation Standard in Chinese, Japanese and Korean

Word Segmentation Standard in Chinese, Japanese and Korean Key-Sun Choi Hitoshi Isahara Kyoko Kanzaki Hansaem Kim Seok Mun Pak Maosong Sun KAIST NICT NICT National Inst. Baekseok Univ. Tsinghua Univ. Daejeon Korea Kyoto Japan Kyoto Japan Korean Lang. Cheonan Korea Beijing China [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Seoul Korea [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] framework), and others in ISO/TC37/SC4 1 . Abstract These standards describe annotation methods but not for the meaningful units of word segmenta- Word segmentation is a process to divide a tion. In this aspect, MAF and SynAF are to anno- sentence into meaningful units called “word tate each linguistic layer horizontally in a stan- unit” [ISO/DIS 24614-1]. What is a word dardized way for the further interoperability. unit is judged by principles for its internal in- Word segmentation standard would like to rec- tegrity and external use constraints. A word ommend what word units should be candidates to unit’s internal structure is bound by prin- ciples of lexical integrity, unpredictability be registered in some storage or lexicon, and and so on in order to represent one syntacti- what type of word sequences called “word unit” cally meaningful unit. Principles for external should be recognized before syntactic processing. use include language economy and frequency In section 2, principles of word segmentation such that word units could be registered in a will be introduced based on ISO/CD 24614-1. lexicon or any other storage for practical re- Section 3 will describe the problems in word duction of processing complexity for the fur- segmentation and what should be word units in ther syntactic processing after word segmen- each language of Chinese, Japanese and Korean. -

Ffifoes LIBRARIES

Combining Linguistics and Statistics for High-Quality Limited Domain English-Chinese Machine Translation By Yushi Xu B.Eng in Computer Science (2006) Shanghai Jiaotong University Submitted to Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June, 2008 © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of the author , Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science r/ I I ',, June, 2008 Certified by Stephanie Seneff Principal Research Scientist Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Terry P.Orlando Chair, Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 0 1 2008 ffifoES LIBRARIES Combining Linguistics and Statistics for High-Quality Limited Domain English-Chinese Machine Translation By Yushi Xu Submitted to Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science On May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science ABSTRACT Second language learning is a compelling activity in today's global markets. This thesis focuses on critical technology necessary to produce a computer spoken translation game for learning Mandarin Chinese in a relatively broad travel domain. Three main aspects are addressed: efficient Chinese parsing, high-quality English-Chinese machine translation, and how these technologies can be integrated into a translation game system. In the language understanding component, the TINA parser is enhanced with bottom-up and long distance constraint features. The results showed that with these features, the Chinese grammar ran ten times faster and covered 15% more of the test set. -

Guidelines for BOLT Chinese-English Word Alignment

Guidelines for BOLT Chinese-English Word Alignment Version 2.0 – April 10, 2014 Linguistic Data Consortium Created by: Xuansong Li [email protected] With contribution from: Niyu Ge [email protected] Stephanie Strassel [email protected] BOLT_WAguide_V2.0 Guidelines for BOLT Word Alignment Annotation Page 1 of 35 Version 2.0 – April 10, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 4 2 DATA ................................................................................................................................................... 4 3 TASKS AND CONVENTIONS ......................................................................................................... 4 3.1 TASKS ............................................................................................................................................ 4 3.2 CONVENTIONS ............................................................................................................................... 5 4 CONCEPTS AND GENERAL APPROACH ................................................................................... 5 4.1 TRANSLATED VERSUS NOT-TRANSLATED ...................................................................................... 6 4.1.1 Translated ............................................................................................................................ 6 4.1.2 Not-translated ..................................................................................................................... -

A Course in Theoretical Chinese Grammar”: Principles and Contradictions

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 116 ( 2014 ) 3147 – 3151 5th World Conference on Educational Sciences - WCES 2013 “A course in theoretical Chinese grammar”: Principles and contradictions Vladimir Kurdyumov * Moscow City Teachers’ Training University Institute of Foreign Languages, Malyi Kazionnyi per., dom.5”B”, Moscow, Russia 105064 Abstract The paper explores the basic principles of “A Course in Theoretical Chinese Grammar” published in Russia as a schoolbook (2005, 2006). Theoretical Grammar is an obligatory course, and the challenge was to create a complete integral conceptual grammar: to show the essence of the language in its unity. And the main problem: existing courses are based on traditional approaches describing adequately the surface structures of inflectional languages, but not applicable for exploring the essence of isolative ones. Chinese syntax is primarily based on the Topic-Comment structures, and the understanding of this point may be viewed as conceptual basis of the language theory at all; Chinese morphology is “positional”: lexical units may fill Positions or “fluctuate” in a Range between several part-of-speech meanings. So the publishing and use of such course may not only improve the theoretical understanding of Chinese and the Language as whole, but also enhance the quality of teaching Chinese as a comprehensive university specialty. © 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. Selection and/or peer-review under responsibility of Academic World Education and Research Center. Keywords: Chinese language; topic-commnet structures;, subject-predicate; theme-rheme; morphology, sinologist, parts of speech 1. Sinologist as a result of education Up to year 2009 there have been five years’ university education in Russia intended for forming professionals; and now Russian universities switched totally to the bachelor's and master's degrees (4+2 years). -

The Syntax of Measure Words in Mandarin Chinese

Taiwan Journal of Linguistics Vol. 9.1, 1-50, 2011 THE CONSTITUENCY OF CLASSIFIER CONSTRUCTIONS IN MANDARIN CHINESE* Niina Ning Zhang ABSTRACT This paper examines the constituency of the construction that contains three elements: a numeral, a word that encodes a counting unit, such as a classifier or measure word, and a noun in Mandarin Chinese. It identifies three structures: a left-branching structure for container measures, standard measures, partitive classifiers, and collective classifiers; a right-branching structure for individual and individuating classifiers; and a structure in which no two of the three elements form a constituent, for kind classifiers. The identification is based on the investigation of four issues: <i> the scope of a left-peripheral modifier; <ii> the dependency between the modifier of unit word and that of a noun; <iii> the complement and predicate status of the combination of a numeral and a unit word; <iv> the semantic selection relation between a unit word and a noun. The paper also shows that the co-occurrence of a numeral and a unit word and the position of certain partitive markers are not reliable in identifying syntactic constituents. It also argues against quantity-individual semantic mappings with different syntactic structures. Finally, the paper presents a comparative deletion analysis of the constructions in which the functional word de follows a unit word. Key words: classifier, measure, constituent, left-branching, right-branching, Chinese * The main arguments of this paper were presented at the 7th Workshop on Formal Syntax & Semantics (FOSS-7), Taipei, April 23-25, 2010. I am grateful to the audience of the workshop. -

Preventing a Troublesome Revision Process Due to Misused Articles

Medical Writing Corner Page 1 of 7 Preventing a troublesome revision process due to misused articles Jeremy Dean Chapnick Editorial Office, AME Publishing Company Correspondence to: Jeremy Dean Chapnick. Editorial Office, AME Publishing Company. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: The English articles (a/an/the) are the most commonly used word in the English language; while simultaneously causing the most trouble for foreign writers during the revision and writing process. In the paper, preventing a troublesome revision process due to misused articles, it will delve deeper into why articles are essential, how to avoid using the wrong one, and the horrible communication mistakes that happen when misusing them. It will also provide authors with some quick tips and tricks for getting articles correct, and to make sure that submitted articles do not have any article problems. Keywords: Indefinite article; definite article; zero article; grammar; foreign writing Received: 07 December 2018; Accepted: 10 December 2018; Published: 14 December 2018. doi: 10.21037/amj.2018.12.04 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/amj.2018.12.04 Part 1: why is using an article important? extremely common. Nearly every manuscript sent to the editor for a check of English language usage and editing will An article is a word that modifies a noun. In the most basic be returned with comments noting that the authors have explanation, there are three English articles, and these misused articles and must further revise. articles tell the reader so much information about a noun. The three written articles are the most commonly used There is the indefinite article, which is a or an, the definite words in the English language, so it is critical that a writer article, which is the, and the zero article, which is no article must master them.