Eastbury Book 2.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelling the Impact of Groundwater Abstractions on Low River Flows

FRIEND: Flow Regimes from International Experimental and Network Data (Proceedings of the Braunschweig Conference, October 1993). IAHS Publ. no. 221, 1994. / / Modelling the impact of groundwater abstractions on low river flows BENTE CLAUSEN Department of Earth Sciences, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade, Denmark ANDREW R. YOUNG & ALAN GUSTARD Institute of Hydrology, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OXW 8BB, UK Abstract A two-dimensional numerical groundwater model was applied to the Lambourn catchment in the UK to predict the impact of ground water abstraction on low river flows for a representative Chalk catch ment. The calibration of the model using observed streamflow and groundwater data is described. A range of abstraction scenarios was simulated to estimate the impact of long term abstraction on monthly river flows as a function of the abstraction rate, seasonality and location. Relationships between low flow statistics and abstraction regimes were derived by analysing a number of simulated hydrographs. INTRODUCTION This paper evaluates the influence of long term groundwater abstractions on low river flows for different abstraction scenarios and different distances from the river using a two-dimensional numerical groundwater model. The objective of the study was to develop a simple numerical model of a typical Chalk catchment which could be used for a sensitivity analysis of the impact of groundwater pumping on streamflow with respect to abstraction regimes. The study is a contribution to the development of regional procedures for providing simple relationships between groundwater pumping and low flows. The study area is the Lambourn catchment on the Berkshire Downs, UK, which lies on the unconfined Chalk aquifer. The Chalk is the major aquifer in the UK both in areal extent and in the quantity and quality of water extracted from it. -

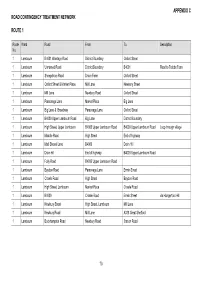

70 Appendix C Road Contingency Treatment

APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 1 Route Ward Road From To Description No. 1 Lambourn B4001 Wantage Road District Boundary Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Unnamed Road District Boundary B4001 Road to Trabbs Farm 1 Lambourn Sheepdrove Road Drove Farm Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Oxford Street & Market Place Mill Lane Newbury Street 1 Lambourn Mill Lane Newbury Road Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Parsonage Lane Market Place Big Lane 1 Lambourn Big Lane & Broadway Parsonage Lane Oxford Street 1 Lambourn B4000 Upper Lambourn Road Big Lane District Boundary 1 Lambourn High Street, Upper Lambourn B4000 Upper Lambourn Road B4000 Upper Lambourn Road Loop through village 1 Lambourn Maddle Road High Street End of highway 1 Lambourn Malt Shovel Lane B4000 Drain Hill 1 Lambourn Drain Hill End of highway B4000 Upper Lambourn Road 1 Lambourn Folly Road B4000 Upper Lambourn Road 1 Lambourn Baydon Road Parsonage Lane Ermin Street 1 Lambourn Crowle Road High Street Baydon Road 1 Lambourn High Street, Lambourn Market Place Crowle Road 1 Lambourn B4000 Crowle Road Ermin Street via Hungerford Hill 1 Lambourn Newbury Street High Street, Lambourn Mill Lane 1 Lambourn Newbury Road Mill Lane A338 Great Shefford 1 Lambourn Bockhampton Road Newbury Road Station Road 70 APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 1 (cont’d) Route Ward Road From To Description No. 1 Lambourn Edwards Hill Station Road High St, Lambourn 1 Lambourn Close End Edwards Hill End of highway 1 Lambourn Greenways Edwards Hill End of highway 1 Lambourn Baydon Road District Boundary A338 via Ermin Street 1 Lambourn Unnamed Road to Ramsbury Ermin Street District Boundary via Membury Industrial Estate 1 Lambourn B4001 B400 Ermin Street District Boundary 1 Lambourn, Newbury Road A338 Great Shefford Oxford Road via Boxford Kintbury & Speen 1 Kintbury High Street, Boxford Rood Hill B4000 Ermin Street 1 Speen Station Road A4 Grove Road 1 Speen Love Lane B4494 Oxford Road B4009 Long Lane 71 APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 2 Route Ward Road From To Description No. -

Shaw-House-Conservation-Area-Management-Plan-Mar-2020.Pdf

Insert front cover. Project Title: Shaw House and Church Conservation Area Management Plan Client: West Berkshire Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked Approved by by 4 December Final Draft Report Graham Keevil John Kate Ahern 2018 Adams Inez Williams Michelle Statton Katie Luxmoore Alex Hardie-Brown 5 November Draft Final Graham Keevil John 2019 Adams Inez Williams Michelle Statton Katie Luxmoore Alex Hardie-Brown 6 November Second Draft Final Graham Keevil John 2019 Adams Inez Williams Michelle Statton Katie Luxmoore Alex Hardie-Brown 7 March Final Graham Keevil John Kate Ahern 2020 Adams Inez Williams Michelle Statton Katie Luxmoore Alex Hardie-Brown Final_Shaw House Conservation Area Management Plan Mar 2020.docx Last saved: 10/03/2020 10:57 Contents 1 Executive summary 1 2 Introduction 3 How to use the Conservation Area Management Plan 3 Main sources 3 Consultation process 4 Acknowledgements 4 3 Historic development 5 Phase I 1581 - 1618 — Thomas Dolman and his son Thomas Dolman II 7 Phase II 1618 - 1666 — Humphrey Dolman 7 Phase III c 1666 - 1697 — Thomas Dolman III 8 Phase IV 1697 - 1711 — Changes made by Sir Thomas Dolman IV 8 Phase V 1728 - 1744 — James Bridges, 1st Duke of Chandos 8 Phase VI 1751 – 1800 — Joseph Andrews 12 Phase VII 1800 - 1851 — Shaw House gardens in the first half of the 19th Century 15 Phase VIII 1851 – 1905 — The Eyre Family 16 Phase IX 1906 - 1939 — The Farquhar Family 18 Phase X 1939 - 1979 21 Phase XI 1980 – onwards 23 4 Shaw House and Church Conservation Area 24 Summary of information -

PRIDDLES FARM WOODSPEEN • Nr NEWBURY

PRIDDLES FARM WOODSPEEN • Nr NEWBURY PRIDDLES FARM WOODSPEEN • Nr NEWBURY PRIDDLES FARM WOODSPEEN • Nr NEWBURY An outstanding Georgian style house in a superb setting Accommodation Ground Floor: Entrance hall • Drawing room • Dining room Sitting room • Kitchen/breakfast room • Cloakroom Lower Ground Floor: Boot room • Hall • Family room Wc • Utility room • 2 store rooms First Floor: Master bedroom suite • 2 further bedroom suites Bedroom 4 • Bathroom Second floor: Bedroom/sitting room and shower room Cottage Sitting room • Kitchen • 2 bedrooms • Shower room Garage block 3 garages • Workshop • Office Stabling • Barn • Swimming pool Garden and grounds In all about 10.046 acres (4.065 ha) The Property Priddles Farm is an outstanding Georgian house The accommodation is well laid out and beautifully and constructed in 2014 to an exceptionally high standard. It is tastefully presented. From the entrance hall, a glazed door an individually designed house that combines the classic leads directly ahead to the dining room with double doors look with modern easy living. Great care has been taken opening to the terrace beyond. To one side of the hall is the in using handmade bricks, windows and doors, and high drawing room with a Bath stone open fireplace fitted with a quality materials throughout. Light and spacious with Jetmaster, and views on three sides looking over the garden. generous ceiling heights, Priddles Farm is a comfortable, To the other side of the hall is a comfortable and cosy sitting practical and stylish family home. room/tv room, also with an open fireplace. The kitchen/breakfast room is spectacular and partly vaulted and opens out with bi-folding doors on the south elevation to the sheltered terrace. -

Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA EQUESTRIAN DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY at UPPER LAMBOURN Maddle Road, Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA

EQUESTRIAN DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Maddle Road, Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA EQUESTRIAN DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY AT UPPER LAMBOURN Maddle Road, Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA Lambourn 2 miles | Wantage 11 miles Marlborough 16 miles Newbury 17 miles | Oxford 27 miles (distances are approximate) A fantastic opportunity to purchase a greenfield site with planning consent for a new training yard in a prime location within the Valley of the Racehorse SITE ON MADDLE ROAD, UPPER SITUATION LAMBOURN The site is situated on the western fringe of the The Property for sale is a green field site with village of Upper Lambourn enjoying far reaching planning consent for a new training yard comprising views over the countryside whilst being only 8 miles a four-bedroom trainers house, 40 boxes, an eight- from the M4 Wickham Interchange. The location on bedroom hostel, storage barn, horse walker and a the edge of Upper Lambourn puts the property at office all set within approximately 2.45 acres (0.99 the heart of the racing community in the area and hectares). Once complete the Property will provide within easy reach of the Jockey Club Estates first superb training facilities in a prime location within class training grounds. the Valley of the Racehorse. The site is near to the village of Lambourn which Planning consent has been granted under provides a range of services including the Valley reference: 19/02596/FULD and permits the Equine Hospital, doctors surgery, a primary construction of the new equestrian training centre school along with various pubs, restaurants and in this prime location. The site affords excellent local shops. -

RIVER KENNET Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)

COUNTY: BERKSHIRE/WILTSHIRE SITE NAME: RIVER KENNET Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) notified under Section 28 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 Local Planning Authorities: Berkshire County Council, Wiltshire County Council, Newbury District Council, Kennet District COuncil National Grid Reference: SU203692 to SU572667 Ordnance Survey Sheet 1:50,000: 174 1:10,000: SU26 NW, SU27 SW, SU27 SE, SU37 SW, SU36 NW, SU36 NE, SU47 NW, SU46 NE, SU56 NW, SU56 NE Date Notified (Under 1981 Act): 1 November 1995 Date of Last Revision: Area: 112.72 ha Other information: The River Lambourn, which is a tributary of the River Kennet, is also an SSSI. There are two existing SSSIs along the River Kennet: Freemans Marsh and Chilton Foliat Meadows. The site boundary is the bank top or, where this is indistinct, the first break of slope. Description and Reasons for Notification The River Kennet has a catchment dominated by chalk with the majority of the river bed being lined by gravels. The Kennet below Newbury traverses Tertiary sands and gravels, London Clay and silt, thus showing a downstream transition from the chalk to a lowland clay river. As well as having a long history of being managed as a chalk stream predominantly for trout, the Kennet has been further modified by the construction of the Kennet and Avon Canal. In some places the canal joins with the river to form a single channel. There are also many carriers and channels formerly associated with water meadow systems. The river flows through substantial undisturbed areas of marshy grassland, wet woodland and reed beds. -

4S Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

4S bus time schedule & line map 4S Newbury - Lambourn via Stockcross, Boxford View In Website Mode The 4S bus line (Newbury - Lambourn via Stockcross, Boxford) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lambourn: 4:10 PM (2) Wash Common: 7:22 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 4S bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 4S bus arriving. Direction: Lambourn 4S bus Time Schedule 34 stops Lambourn Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:10 PM Newbury Wharf, Newbury Wharf Road, Newbury Tuesday 4:10 PM Park Way, Newbury Wednesday 4:10 PM Parkway, Newbury Thursday 4:10 PM Park Way Top, Newbury Friday 4:10 PM Park Way, Newbury Saturday Not Operational Oxford Street, Newbury Oxford Street, Newbury Leys Gardens, Newbury Jesmond Dene, Newbury 4S bus Info Direction: Lambourn Speen Lane Foot, Newbury Stops: 34 Trip Duration: 45 min Coxeter Road, Speen Line Summary: Newbury Wharf, Newbury, Park Way, Coxeter Road, Speen Civil Parish Newbury, Park Way Top, Newbury, Oxford Street, Newbury, Leys Gardens, Newbury, Speen Lane Foot, Kersey Crescent, Speen Newbury, Coxeter Road, Speen, Kersey Crescent, Speen, Sutton Road, Speen, The Sydings, Speen, Hare Sutton Road, Speen And Hounds, Speen, Deanwood House, Stockcross, Sutton Road, Speen Civil Parish Foley Lodge, Stockcross, Snake Lane, Stockcross, Stockcross Post O∆ce, Stockcross, Coomesbury The Sydings, Speen Lane, Wickham Heath, Easton Hill Turn, Wickham, Station Road, Speen Civil Parish Wickham Cross Roads, Wickham, Wickƒeld Farm, Shefford -

Summer BCP Evensong Sunday 21St July 6Pm Fawley. All Are Welcome Flower Displays in the Churches and Open Gardens from 11Am To

t WEST DOWNLAND BENEFICE NOTICES Brightwalton with Catmore, Chaddleworth, Fawley, Great Shefford with Shefford Woodlands, Leckhampstead and Welford with Wickham TODAY Summer BCP Evensong th Sunday 7 July – the Third Sunday after Trinity Sunday 21st July 6pm Fawley. All are welcome 9.30am Holy Communion at Fawley 11.00am Holy Communion at Wickham 2.00pm Baptism at Fawley. 5.15pm ‘Thanksgiving for the Natural World’ at Great Shefford. WELCOME Flower displays in the churches and Open “Being sent out” Gardens from 11am to 5pm in Great Shefford Today’s Gospel Reading begins with the wonderful and Shefford Woodlands: Sunday 7th July - vision of God “sending out his people” in order to cream teas, plants, cakes and jams & jellies stalls spread the Word of God to every town and place. He available in the village hall. The day will end with warns; it will not be easy, in fact it will be hard, but a short service ‘Giving thanks for the natural trust in the Lord and be glad in the task. Travel light, world’ at St Mary’s Church at 5.15pm the Lord says, “carry no purse, no bag, no sandals; and greet no one on the road”. We are all called, as the body of Christ, to administer God’s word in every Welford and Wickham Primary School Summer place and to all. Deacons are called to a particular Production. This year the children are ministry; to serve. First and foremost, to serve God, by giving their lives to his service and secondly to presenting ‘Blast Off!’ at Arlington Arts on th serve others with humility and love. -

Caspian House, High Street, Upper Lambourn, Hungerford, Berkshire RG17 8QT D

Caspian House, High Street, Upper Lambourn, Hungerford, Berkshire RG17 8QT D D CASPIAN HOUSE, HIGH STREET, UPPER LAMBOURN, HUNGERFORD BERKSHIRE RG17 8QT LAST ONE REMAINING! Part exchange considered. A very rare opportunity indeed. The chance to purchase a new four bedroom house in a secluded hamlet at the foot of the Downs built by Pomroy and Hine in association with Rivar. The house has been completed to the very high specification associated with Rivar Homes who are developing on behalf of Pomroy and Hine. LOCATION Upper Lambourn is located within the stunning Lambourn Valley which is widely recognised as a major centre for horse racing. It is within 7.5 miles of junction 14 of the M4 and 15.5 miles to Newbury rail station with direct fast trains to London Paddington and the West County. Hungerford train station is 10.1 miles away. On it's doorstep is the village of Lambourn with a selection of local shops, a doctors surgery, a church and pubs. Upper Lambourn is also approximately 10 miles from Wantage and Hungerford. DIRECTIONS From Downer & Co's offices in Newbury, join the A339 northbound and follow signs to the M4 (junction 13). Join M4 westbound and exit at the next junction, 14, for Hungerford and take the third exit heading north on the A338. Take the first left onto the B4000 towards Lambourn and continue for approximately 3.1 miles turning right into Lambourn. On entering Lamborn, turn first left on the High Street sign posted Upper Lambourn. On entering Upper Lambourn, take the fourth right turn into High Street where Caspian House will be on the left hand side. -

4C Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

4C bus time schedule & line map 4C Lambourn - Newbury via Great Shefford, B4000 View In Website Mode The 4C bus line (Lambourn - Newbury via Great Shefford, B4000) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newbury: 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM (2) Wash Common: 7:22 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 4C bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 4C bus arriving. Direction: Newbury 4C bus Time Schedule 37 stops Newbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM Market Square, Lambourn Lion Mews, Lambourn Tuesday 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM Millƒeld, Lambourn Wednesday 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM Mill Lane, Lambourn Thursday 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM Mill Lane, Lambourn Friday 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM Woodbury, Lambourn Saturday 7:22 AM - 6:31 PM Newbury Road, Lambourn Civil Parish Long Hedge, Bockhampton The Hermitage, Eastbury 4C bus Info Direction: Newbury The Plough, Eastbury Stops: 37 Trip Duration: 46 min Straight Lane, Eastbury Line Summary: Market Square, Lambourn, Millƒeld, Lambourn, Mill Lane, Lambourn, Woodbury, Horseshoe Cottage, Eastbury Lambourn, Long Hedge, Bockhampton, The Hermitage, Eastbury, The Plough, Eastbury, Straight Westƒeld Farm, East Garston Lane, Eastbury, Horseshoe Cottage, Eastbury, Westƒeld Farm, East Garston, Humphreys Lane, East Garston, Queens Arms, East Garston, Maidencourt Humphreys Lane, East Garston Farm, East Garston, The Swan, Great Shefford, Village Access Road, Shefford Woodlands, Wickƒeld Queens Arms, East Garston Farm, Shefford Woodlands, Wickham Cross Roads, Wickham, -

Chaddleworth News 2021 May

May 2021 Chaddleworth News In this edition… RAF Welford RAF Welford news and history, Located within the North Wessex Downs updates from West Berkshire Council, Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and the latest news from the people and organisations (AONB) is RAF Welford and we are very local to our Chaddleworth community… blessed to be able to operate in such a beautiful location. The base is keen to maintain a quality The Ibex Inn THANK YOU to everyone relationship with the surrounding area, and has recently who has popped out and supported us over been working with the AONB committee to discuss the view the recent days! It is great to see so many across the base following some construction work. The of you. AONB committee would like to preserve the skyline We can safely seat 70 people in our garden following the erection of lightning protection poles and it has and have a heated marquee. Booking is advised but not been agreed that RAF Welford will plant 384 trees, in order essential. Currently, because of the current government to obscure the new construction. The trees will include 23 restrictions, we are only able to provide table service. wild cherry trees, and the rest are mainly Field Maple and Not booked and just fancied popping in? Email Beech. The tree planting is set for later in the Fall when the saplings of appropriate size are available. We are very [email protected] or call 01488 639052 pleased to maintain our relationships and ensure that the base remains in keeping with the surrounding area. -

Open 10 Mile Time Trial Course H10/3A

Open 10 mile Time Trial Course H10/3A Saturday 17th September 2016 at 14:00 Event Secretary Adam Evans 49 Huntingdon Gardens Newbury RG14 2RT Tel: 07900 904143 IMPORTANT: THE EVENT HQ IS IN A DIFFERENT LOCATION FROM LAST YEAR. BOXFORD VILLAGE HALL IS APPROX 5½ MILES FROM THE START SO PLEASE ALLOW ENOUGH TIME TO REACH THE START. Event Headquarters – Open from 12:45: Boxford Village Hall, Lambourn Road, Boxford, Newbury, Berks. RG20 8DD Event headquarters OS map reference is SU422717 (OS Landranger 174, Newbury & Wantage) Timekeeper: Mrs Marion Fountain, Didcot Phoenix CC Assistant Timekeeper: Mr David Canning, Newbury Road Club Promoted by the West London Cycling Association. This event is being run for and on behalf of Cycling Time Trials under their rules and regulations. In the interests of your own safety, Cycling Time Trials and the event promoters strongly advise that riders wear a HARD SHELL HELMET that meets an internationally accepted safety standard. Further details of these may be found in the CTT Handbook. Important Notes: Riders must sign on and collect their number from HQ. This event may be subject to a Doping Control - It is your responsibility to check by returning to the HQ as soon as possible after you finish. Riders must not ride through the finish when not competing, riders doing so, risk disqualification. Please be considerate to others when parking your vehicle. Take care when entering the HQ car park as there is an overhead barrier. Please do NOT park on or near the course, especially the start (this is a private road) or in Shefford Woodlands.