Arthur Miller's “Finishing the Picture”: Art As Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

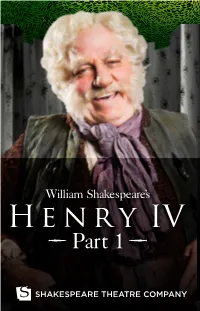

Program from the Production

STC Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Stephen A. Hopkins Emeritus Trustees Michael R. Klein, Chair Lawrence A. Hough R. Robert Linowes*, Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair W. Mike House Founding Chairman John Hill, Treasurer Jerry J. Jasinowski James B. Adler Pauline Schneider, Secretary Norman D. Jemal Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Scott Kaufmann David A. Brody* Kevin Kolevar Melvin S. Cohen* Trustees Abbe D. Lowell Ralph P. Davidson Nicholas W. Allard Bernard F. McKay James F. Fitzpatrick Ashley M. Allen Eleanor Merrill Dr. Sidney Harman* Stephen E. Allis Melissa A. Moss Lady Manning Anita M. Antenucci Robert S. Osborne Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Stephen M. Ryan William F. McSweeny Afsaneh Beschloss K. Stuart Shea V. Sue Molina William C. Bodie George P. Stamas Walter Pincus Landon Butler Lady Westmacott Eden Rafshoon Dr. Paul Carter Rob Wilder Emily Malino Scheuer* Chelsea Clinton Suzanne S. Youngkin Lady Sheinwald Dr. Mark Epstein Mrs. Louis Sullivan Andrew C. Florance Ex-Officio Daniel W. Toohey Dr. Natwar Gandhi Chris Jennings, Sarah Valente Miles Gilburne Managing Director Lady Wright Barbara Harman John R. Hauge * Deceased 3 Dear Friend, Table of Contents I am often asked to choose my favorite Shakespeare play, and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 Title Page 5 it is very easy for me to answer immediately Henry IV, Parts 1 The Play of History and 2. In my opinion, there is by Drew Lichtenberg 6 no other play in the English Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 1 9 language which so completely captures the complexity and Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 2 10 diversity of an entire world. -

Marilyn Monroe, Lived in the Rear Unit at 5258 Hermitage Avenue from April 1944 to the Summer of 1945

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-2179-HCM ENV-2015-2180-CE HEARING DATE: June 18, 2015 Location: 5258 N. Hermitage Avenue TIME: 10:30 AM Council District: 2 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: North Hollywood – Valley Village 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: South Valley Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Valley Village 90012 Legal Description: TR 9237, Block None, Lot 39 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the DOUGHERTY HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Hermitage Enterprises LLC c/o Joe Salem 20555 Superior Street Chatsworth, CA 91311 APPLICANT: Friends of Norma Jean 12234 Chandler Blvd. #7 Valley Village, CA 91607 Charles J. Fisher 140 S. Avenue 57 Highland Park, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. NOT take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation do not suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of Planning [SIGN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2015-2179-HCM 5258 N. Hermitage, Dougherty House Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The corner property at 5258 Hermitage is comprised of two one-story buildings. -

SUPPLEMENTS 92373 01 1-240 R2mv.Qxd 7/24/10 12:06 AM Page 193

92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 12:17 AM Page 225 SUPPLEMENTS 92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 12:06 AM Page 193 Note: It is very likely that this letter was written at the beginning of 1956, during the filming of Joseph Logan’s Bus Stop, when Paula Strasberg worked as Marilyn’s coach for the first time. 92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 1:16 AM Page 194 92373_01_1-240_r2mv.qxd 7/24/10 12:07 AM Page 195 Dear Lee & Paula, Dr. Kris has had me put into the New York Hospital—psychiatric division under the care of two idiot doctors—they both should not be my doctors. You haven’t heard from me because I’m locked up with all these poor nutty people. I’m sure to end up a nut if I stay in this nightmare—please help me Lee, this is the last place I should be—maybe if you called Dr. Kris and assured her of my sensitivity and that I must get back to class so I’ll be better prepared for “Rain.” Lee, I try to remember what you said once in class “that art goes far beyond science.” And the scary memories around me I’d like to forget—like screaming woman etc. Please help me—if Dr. Kris assures you I am all right—you can assure her I am not. I do not belong here! I love you both. Marilyn P.S. forgive the spelling—and there is nothing to write on here. I’m on the dangerous floor!! It’s like a cell can you imagine—cement blocks. -

FINISHING the PICTURE by Arthur Miller

Press Information ! ! ! VIBRANT NEW WRITING | UNIQUE REDISCOVERIES June–August Season 2018 The UK premiere of Arthur Miller’s final play FINISHING THE PICTURE by Arthur Miller. Directed by Phil Willmott. Set Design by Isabella Van Braeckel. Costume Design by Penn O’Gara. Lighting Design by Rachel Sampley. Sound Design by Nicola Chang. Presented by Nastazja Somers for The Phil Willmott Company in association with the Finborough Theatre. Cast: Patrick Bailey. Stephen Billington. Jeremy Drakes. Nicky Goldie. Rachel Handshaw. Oliver Le Sueur. Tony Wredden. "She is frightened and resentful and angry – and we’ve got about half an hour to cure all three.” Following his critically acclaimed, up-close reinvention of Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy and sell-out revival of The American Clock, multi-award-winning director Phil Willmott brings the intense focus of the intimate Finborough Theatre to bear on Miller’s final work, Finishing The Picture, opening for a four week limited season on Tuesday, 12 June 2018 (Press Nights: Thursday, 14 June 2018 and Friday, 15 June 2018 at 7.30pm.) As the women of today’s Hollywood campaign for dignity and equality, Finishing the Picture is a razor sharp psychological study of an abused, misunderstood female star and the havoc her unpredictability brings to a film set in 1961. Inspired by the filming of The Misfits, the screenplay Miller wrote for his then wife, Marilyn Monroe, and focused on the bemused and exasperated director, screen writer, producer, acting coaches and crew that closely mirror the real life production team of The Misfits – and whilst leading lady Kitty shares many characteristics with Monroe herself, Finishing the Picture – Arthur Miller’s very final play – is a devastating indictment of how a male-dominated movie industry inadvertently destroyed a vulnerable young woman, even as they transformed her into a screen goddess, and how they were unable to deal with the wreckage they caused. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

The Crucible

Political Issues A Playgoer’s Guide to Several works written by Arthur Miller dealt with political issues. For example, Death of a Salesman dealt with the American ideal of capitalism and power. In the case of The Crucible, to quote Arthur Miller, it was THE CRUCIBLE written with the intent “to use the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for by Arthur Miller McCarthyism.” The definition of McCarthyism is "the practice of publicizing accusations of political disloyalty or subversion with The Author insufficient regard to evidence.” During the 1950s, the United States cracked down on communists, potential communists, or supporters of Arthur Miller was born on October 17, 1915 in New York City. He has Communism. Similar in many ways to the witch trials of 1692, many enriched the Broadway stage for several decades and has made a reputation Americans were accused of being supportive to the communist party. The for dealing with contemporary, political, and moral issues. Miller began “Red Hunt,” as it were, was led by the House Committee on Un-American writing plays while attending the University of Michigan, where several of Activities and by Senator Joseph R. McCarthy. his dramatic efforts were rewarded with prizes. Miller was married three times in his life, first to Mary Grace Slattery, his high school sweetheart, “The ultimate terror of our lives should be faced,” Miller once said, secondly to Marilyn Monroe, and then to Ingeborg Morath. “namely our own sadism, our own ability to obey orders from above, our own fear of standing firm on humane principle against the obscene power Miller wrote 25 plays in the course of his life. -

Arthur Miller's Contentious Dialogue with America

Louise Callinan Revered Abroad, Abused at Home: Arthur Miller’s contentious dialogue with America A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at St Patrick’s College, Dublin City University Supervisor: Auxiliary Supervisor: Dr Brenn a Clarke Dr Noreen Doody Dept of English Dept of English St Patrick’s College St Patrick’s College Drumcondra Drumcondra May 2010 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has-been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: Qoli |i/U i/|______________ ID No.: 55103316 Date: May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever indebted to Dr. Brenna Clarke for her ‘3-D’ vision, and all that she has so graciously taught me. A veritable fountain of knowledge, encouragement, and patient support, she- has-been a formative force to me, and will remain a true inspiration. Thank you appears paltry, yet it is deeply meant and intended as an expression of my profound gratitude. A sincere and heartfelt thank you is also extended to Dr. Noreen Doody for her significant contribution and generosity of time and spirit. Thank you also to Dr. Mary Shine Thompson, and the Research Office. A special note to Sharon, for her encyclopaedic knowledge and ‘inside track’ in negotiating the research minefield. This thesis is an acknowledgement of the efforts of my family, and in particular the constant support of my parents. -

STACY KEACH RETURNS to WASHINGTON to STAR in King Lear at SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY JUNE 16-JULY 19

We’re going green! Over the next few months, STC will be transitioning to electronic distribution for all press releases. We don’t want lose contact with you! Please provide us with your email address so that we can continue to send our press releases to you. For Immediate Release Media Contact: Amy Scott-Douglass May 22, 2009 202.547.3230 ext. 2312 [email protected] STACY KEACH RETURNS TO WASHINGTON TO STAR IN King Lear AT SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY JUNE 16-JULY 19 Remount of Critically-Acclaimed Production by Tony Award-winning Director Robert Falls WASHINGTON, D.C.— Two theatre greats—actor Stacy Keach and director Robert Falls—have teamed up to bring one of the most powerful dramas in Western literature to the Shakespeare Theatre Company. Keach will star in Falls’ remount of his critically-acclaimed production of King Lear at Sidney Harman Hall (610 F Street NW) from June 16 to July 19, 2009. Tony Award-winning director Falls’ provocative, graphic production captures both the stark violence and the devastating passion of Shakespeare's masterpiece. Seeking to place King Lear in “a very specific time and place,” Falls chose war-torn 1990s Yugoslavia as the setting. “I wanted to challenge myself,” says Falls, “into thinking about theatre and about life in a more immediate, contemporary, daring way.” When the production premiered at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre in 2006, The Chicago Tribune called it “a colossal, eye-popping operatic production,” and The New York Times proclaimed it one of the best productions of 2006. “It’s the production I’m most proud of in my career,” says Falls, “so I’m thrilled to be doing it at the Shakespeare Theatre Company.” Fresh off his Helen Hayes Award-winning performance in Frost-Nixon, Stacy Keach returns to STC to star as the tempestuous patriarch. -

100 Years on the Road, 108 a Christmas Carol, 390 a Cool Million, 57 a Memory of Two Mondays, 6, 129, 172, 173, 200, 211 a Natio

Cambridge University Press 0521844169 - Arthur Miller: A Critical Study Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX 100 Years on the Road,108 Ann Arbor, 12 Anna Karenina,69 A Christmas Carol,390 Anti-Semitism, 13, 14, 66, 294, 330, A Cool Million,57 476, 485, 488 AMemoryofTwoMondays,6,129,172, Apocalypse Now,272 173, 200, 211 Arden, John, 157 A Nation of Salesmen,107 Arendt, Hannah, 267, 325 APeriodofGrace, 127 Arnold, Eve, 225 A Search for a Future,453 Aronson, Boris, 251 A Streetcar Named Desire, 98, 106, 145 Artaud, Antonin, 283 A View from the Bridge, 157, 173, 199, Arthur Miller Centre, 404 200, 202, 203, 206, 209, 211, 226, Auschwitz–Birkenau, 250, 325, 329, 351, 459 471 Abel, Lionel, 483 Awake and Sing, 13, 57, 76 Actors Studio, 212 Aymee,´ Marcel, 154, 156 Adorno, Theodore, 326 After the Fall, 5, 64, 126, 135, 166, 203, ‘Babi Yar’, 488 209, 226, 227, 228, 248, 249, 250, Barry, Phillip, 18 257, 260, 264, 267, 278, 280, 290, Barton, Bruce, 427 302, 308, 316, 322, 327, 329, 331, BBC, 32 332, 333, 334, 355, 374, 378, 382, Beckett, Samuel, 120, 175, 199, 200, 386, 406, 410, 413, 415, 478, 487, 488 204, 209, 250, 263, 267, 325, 328, Alger, Horatio Jr., 57, 113 329, 387, 388, 410, 475 All My Sons,1,13,17,42,47,64,76,77, Bel-Ami,394 98, 99, 132, 136, 137, 138, 140, 197, Belasco, David, 175 288, 351, 378, 382, 388, 421, 432, 488 Bell, Daniel, 483 Almeida Theatre, 404, 416 Bellow, Saul, 74, 236, 327, 372, 376, Almost Everybody Wins,357 436, 470, 471, 472, 473, 483 American Clock, The, 337 Belsen, 325 American Federation of Labour, 47 -

Marilyn Monroe's Star Canon: Postwar American Culture and the Semiotics

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2016 MARILYN MONROE’S STAR CANON: POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE AND THE SEMIOTICS OF STARDOM Amanda Konkle University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.038 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Konkle, Amanda, "MARILYN MONROE’S STAR CANON: POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE AND THE SEMIOTICS OF STARDOM" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--English. 28. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/28 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Arthur Miller's the Crucible

Bloom’s GUIDES Arthur Miller’s The Crucible New Edition CURRENTLY AVAILABLE Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Joy Luck Club All the Pretty Horses The Kite Runner Animal Farm Lord of the Flies The Autobiography of Malcolm X Macbeth The Awakening Maggie: A Girl of the Streets The Bell Jar The Member of the Wedding Beloved The Metamorphosis Beowulf Native Son Black Boy Night The Bluest Eye 1984 Brave New World The Odyssey The Canterbury Tales Oedipus Rex Catch-22 Of Mice and Men The Catcher in the Rye One Hundred Years of Solitude The Chosen Pride and Prejudice The Crucible Ragtime Cry, the Beloved Country A Raisin in the Sun Death of a Salesman The Red Badge of Courage Fahrenheit 451 Romeo and Juliet A Farewell to Arms The Scarlet Letter Frankenstein A Separate Peace The Glass Menagerie Slaughterhouse-Five The Grapes of Wrath Snow Falling on Cedars Great Expectations The Stranger The Great Gatsby A Streetcar Named Desire Hamlet The Sun Also Rises The Handmaid’s Tale A Tale of Two Cities Heart of Darkness Their Eyes Were Watching God The House on Mango Street The Things They Carried I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings To Kill a Mockingbird The Iliad Uncle Tom’s Cabin Invisible Man The Waste Land Jane Eyre Wuthering Heights Bloom’s GUIDES Arthur Miller’s The Crucible New Edition Edited & with an Introduction by Harold Bloom Bloom’s Guides: The Crucible—New Edition Copyright © 2010 by Infobase Publishing Introduction © 2010 by Harold Bloom All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Arthur Miller

PUSHING THE LIMIT: AMERICAN INDUSTRY DURING WORLD WAR II The American home front during World War II is essen- men were perishing on the European and Pacific fronts. It conditioners, washing machines and dryers, etc.) to com- tially a lesson in basic economics: as demand for war was a dichotomy that was both unconscionable and un- plex tank and aircraft parts. materiel skyrocketed, supply congruously followed avoidable, given the desperate need for material and the The automobile industry, for example, produced z suit—fueled by a workforce that previously had seen inevitable profits earned from producing it. roughly three million cars in 1941. However, in the years unemployment figures of 24.9 percent just eight years As early as December 1941, spending on military pre- following Pearl Harbor, fewer than 400 new vehicles were earlier. In the words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt: paredness had reached a stunning $75 million a day. Over manufactured as the factories were retooled to produce “Dr. New Deal was replaced by Dr. Win the War.” the next four years war material production continued to tanks, aircraft and military trucks. The demand for planes The aircraft industry is prime example of this surge in skyrocket: By 1945, the United States had produced more was so high that pilots were known to sleep on cots out- national production: In May 1940, during the same than 88,000 tanks, 257,000 artillery weapons, 2,679,000 side the major plants, waiting to fly the planes away as week The Netherlands government surrendered to machine guns, 2,382,000 military trucks and 324,000 war- they came off the production lines.