Arthur Miller's the Crucible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

295 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-74538-3 - The Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller, Second Edition Edited by Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX Aarnes, William 281 Miller on 6, 152, 161 Abbott, Anthony S. 279 and No Villain/They Too Arise 6, 25, 28 “About Theatre Language” 76 productions xiii, 159, 161, 162 Ackroyd, Peter 166–67 revisions 160, 161 Actors’ Studio 220, 226 American Legion 215 Adding Machine, The 75 Anastasia, Albert 105 Adler, Thomas P. 84n, 280, 284 Anastasia, Tony 105, 108n Adorno, Theodor 201 Anderson, Maxwell 42 After the Fall xii, xiii, 4, 8, 38, 59–60, 61, Angel Face 209 118, 120–26, 133, 139, 178, 186, 262, Another Part of the Forest 285 265, 266 Anthony Adverse 216 changing critical reception 269–70 Antler, Joyce 290 The Last Yankee and 178 Archbishop’s Ceiling, The 5–6, 8, 141, Miller on 54–55, 121–22, 124, 126, 265 145–51, 167, 168 productions xii, xiii, 121, 123, 124–25, Miller on 147, 148, 152 156–57, 270, 283 productions xiii, 159, 161–62 The Ride Down Mount Morgan and 173 revisions 141, 159, 161, 162n structure 7, 128 Aristotle 13, 64, 234, 264 studies of 282, 284–85, 288, 290, 293 Aronson, Boris 129 viewed as autobiographical/concerned Art of the Novel, The 237n with Monroe 4, 121, 154, 157, 195, Arthur Miller Centre for American Studies 269, 275 (UEA) xiv, xv, 162 Ajax 13 Arthur Miller Theatre, University of Albee, Edward 154 Michigan xv Alexander, Jane 165 Aspects of the Novel 235 All My Sons xi, 2, 4, 36–37, 47, 51–62, 111, Asphalt Jungle, The 223 137, 209, 216, 240, 246, 265 Assistant, The 245 film versions xiv, 157–58, 206–12, 220, Atkinson, Brooks 293 232 Auden, W. -

A Production Analysis of Arthur Miller's the Price

BELL, LOUIS P. A Production of Arthur Miller's The Price. (1976) Directed by: Dr. Herman Middleton. Pp. 189 The purpose of this thesis is to study the background surrounding the playwright and the play itself in preparation for a production of the play, and then present a critical evaluation of the production. Chapter One deals with the following: (1) research of the playwright's background, (2) research of the play's back- ground, (3) character description and analysis, (4) analysis of the set, (5) the director's justification of script, and (6) the director's interpretation of that script. Chapter Two consists of the prompt book for the pro- duction, performed October 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and 28, in Taylor Theatre at the University of North Carolina at Greens- boro. Notations include: (1) movement, composition, and picturization, (2) details of characterization and stage business, (3) rhythm and tempo, and (4) lighting and sound cues, production photographs are also included. The third chapter consists of critical evaluations in four areas. They are: (1) achievement of Interpretation, (2) actor-director relationships, (3) audience response, and (4) personal comments. A PRODUCTION ANALYSIS OF ARTHUR MILLER'S THE PRICE by Louis Bell A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Greensboro 1976 Thesis Adviser APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

FINISHING the PICTURE by Arthur Miller

Press Information ! ! ! VIBRANT NEW WRITING | UNIQUE REDISCOVERIES June–August Season 2018 The UK premiere of Arthur Miller’s final play FINISHING THE PICTURE by Arthur Miller. Directed by Phil Willmott. Set Design by Isabella Van Braeckel. Costume Design by Penn O’Gara. Lighting Design by Rachel Sampley. Sound Design by Nicola Chang. Presented by Nastazja Somers for The Phil Willmott Company in association with the Finborough Theatre. Cast: Patrick Bailey. Stephen Billington. Jeremy Drakes. Nicky Goldie. Rachel Handshaw. Oliver Le Sueur. Tony Wredden. "She is frightened and resentful and angry – and we’ve got about half an hour to cure all three.” Following his critically acclaimed, up-close reinvention of Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy and sell-out revival of The American Clock, multi-award-winning director Phil Willmott brings the intense focus of the intimate Finborough Theatre to bear on Miller’s final work, Finishing The Picture, opening for a four week limited season on Tuesday, 12 June 2018 (Press Nights: Thursday, 14 June 2018 and Friday, 15 June 2018 at 7.30pm.) As the women of today’s Hollywood campaign for dignity and equality, Finishing the Picture is a razor sharp psychological study of an abused, misunderstood female star and the havoc her unpredictability brings to a film set in 1961. Inspired by the filming of The Misfits, the screenplay Miller wrote for his then wife, Marilyn Monroe, and focused on the bemused and exasperated director, screen writer, producer, acting coaches and crew that closely mirror the real life production team of The Misfits – and whilst leading lady Kitty shares many characteristics with Monroe herself, Finishing the Picture – Arthur Miller’s very final play – is a devastating indictment of how a male-dominated movie industry inadvertently destroyed a vulnerable young woman, even as they transformed her into a screen goddess, and how they were unable to deal with the wreckage they caused. -

Biblioteques De L'hospitalet

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA April 16, 2020 All My Sons Arthur Miller « The success of a play, especially one's first success, is somewhat like pushing against a door which suddenly opens from the other side. One may fall on one's face or not, but certainly a new room is opened that was always securely shut until then. For myself, the experience was invigorating. It made it possible to dream of daring more and risking more. The audience sat in silence before the unwinding of All My Sons and gasped when they should have, and I tasted that power which is reserved, I imagine, for Contents: playwrights, which is to know that by one's invention Introduction 1 a mass of strangers has been publicly transfixed. Author biography 2-3 Arthur Miller All My Sons - 4 Introduction & Context All My Sons - 5-6 » Themes Notes 7 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_My_Sons] Page 2 Author biography Arthur Miller is considered Street Crash of 1929, and had to Willy Loman, an aging Brooklyn one of the greatest American move from Manhattan to salesman whose career is in playwrights of the 20th Flatbush, Brooklyn. After decline and who finds the values century. His best-known plays graduating high school, Miller that he so doggedly pursued have include 'All My Sons,' 'The worked a few odd jobs to save become his undoing. Crucible' and the Pulitzer enough money to attend the Prize-winning 'Death of a University of Michigan. While in Salesman won Miller the highest Salesman.' college, he wrote for the student accolades in the theater world: paper and completed his first the Pulitzer Prize, the New York Who Was Arthur Miller? play, No Villain, for which he won Drama Critics' Circle Award and the school's Avery Hopwood the Tony for Best Play. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

All My Sons As Precursor in Arthur Miller's Dramatic World

All My Sons as Precursor in Arthur Miller’s Dramatic World Masahiro OIKAWA※ Abstract Since its first production in 1947, Arthur Miller’s All My Sons has been performed and appreciated worldwide. In academic studies on Miller, it secures an important place as a precursor, because it has encompassed such themes as father-son conflict, pursuit of success dream in the form of a traditional tragedy as well as a family and a social play. As for techniques, to begin with, the Ibsenite method of dramatization of the present critical situation and presentation of the past “with sentimentality” are obvious. Secondly, the biblical tale of Cain and Abel from the Old Testament allows the play to disguise itself as a modern morality play on “brotherly love.” Thirdly, Oedipus’s murder of his father in Oedipus Rex is used symbolically to place the play in the Western tradition of drama. Taking all these major themes and techniques into account, the paper argues that the play is dramatizing the universal, and that by looking at the conflict between father and son, we can understand why Miller’s message in All My Sons is significant for Japanese andiences. I. Introducion Most of the reviews appearing in the major newspapers and magazines on All My Sons (1947) were rather favorable, which is quite understandable considering that the play vividly depicts the psychological aspects of the United States during and immediately after the Second World War in a realistic setting. In fact, it is impossible to understand the problems Joe and Chris Keller, the father and the son, get involved in without the background of the war. -

Death of a Salesman

Belvoir presents DEATH OF A SALESMAN Photo: Michael Corridore By Arthur Miller Director Simon Stone RESOURCES for Teachers Death of a Salesman – Belvoir Teacher’s Resources – p 1 DEATH OF A SALESMAN By ARTHUR MILLER Director SIMON STONE Set Designer RALPH MYERS Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer & Sound Designer STEFAN GREGORY Assistant Director JENNIFER MEDWAY Fight Choreographer SCOTT WITT Stage Managers LUKE McGETTIGAN, MEL DYER (from 31 July) Assistant Stage Managers MEL DYER, CHANTELLE FOSTER (from 31 July) Stage Management Secondment GRACE NYE-BUTLER With: The Woman / Jenny / Miss Forsythe BLAZEY BEST Biff PATRICK BRAMMALL Willy Loman COLIN FRIELS Ben STEVE LE MARQUAND Linda / Letta GENEVIEVE LEMON Happy HAMISH MICHAEL Charley / Stanley PIP MILLER Bernard / Howard LUKE MULLINS Belvoir’s production of Death of a Salesman opened at Belvoir St Theatre on Wednesday 27 June 2012. Colin Friels Photo: Heidrun Löhr Death of a Salesman – Belvoir Teacher’s Resources – p 2 INTRODUCTION Arthur Miller and Death of a Salesman . Arthur Miller is widely regarded as one of the greatest twentieth century dramatists. Over the course of his career, he wrote around 35 stage plays, the best known of which include Death of a Salesman (1949), All My Sons (1947), The Crucible (1953), A View from the Bridge (1955) and The Price (1968). He is also known for his many screenplays, radio plays and essays. Death of a Salesman premiered on Broadway on the 10th February 1949. Initial reviews praised the play for its emotional intensity and dramatic impact, along with the innovatively fluid approach to time and space that its narrative takes. -

Arthur Miller's Contentious Dialogue with America

Louise Callinan Revered Abroad, Abused at Home: Arthur Miller’s contentious dialogue with America A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at St Patrick’s College, Dublin City University Supervisor: Auxiliary Supervisor: Dr Brenn a Clarke Dr Noreen Doody Dept of English Dept of English St Patrick’s College St Patrick’s College Drumcondra Drumcondra May 2010 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has-been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: Qoli |i/U i/|______________ ID No.: 55103316 Date: May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever indebted to Dr. Brenna Clarke for her ‘3-D’ vision, and all that she has so graciously taught me. A veritable fountain of knowledge, encouragement, and patient support, she- has-been a formative force to me, and will remain a true inspiration. Thank you appears paltry, yet it is deeply meant and intended as an expression of my profound gratitude. A sincere and heartfelt thank you is also extended to Dr. Noreen Doody for her significant contribution and generosity of time and spirit. Thank you also to Dr. Mary Shine Thompson, and the Research Office. A special note to Sharon, for her encyclopaedic knowledge and ‘inside track’ in negotiating the research minefield. This thesis is an acknowledgement of the efforts of my family, and in particular the constant support of my parents. -

Arthur Miller at the Alley

ARTHUR MILLER AT THE ALLEY Arthur Miller is often regarded as one of the greatest literary minds of the twentieth century, so it is no surprise that the Alley Theatre has produced so much of his work. From Alley Theatre founder Nina Vance’s production of Death of a Salesman in 1954, to Gregory Boyd’s production of The Crucible in 1994, to the Alley’s most recent production of All My Sons in 2015, the Alley Theatre has a rich history of producing Miller’s plays over the last 70 seasons. Our current production of A View from the Bridge marks the sixteenth Arthur Miller production at the theatre and the fourth time the play has been produced on the Alley stage. As we celebrate Miller’s legacy, we look back at the history of Arthur Miller at the Alley. ¡ ¢ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¤ ¦ § ¨ © ¤ ¤ £ ¤ ¦ ¤ ¦ ¤ . £ ¡ ¤ ¡ ¢ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¤ ¦ 1954 | Death of a Salesman 1955 | all my sons 1957 | a view from the bridge TRIVIA A View from the Bridge first premiered on Broadway, in a one-act version, in which year? 1A. 1955 C. 1960 ¢ ¤ ¤ ¤ £ B. 1957 D. 1962 ¤ ¥ ¥ £ ¤ ¡ ¥ ¥ ¦ ¡ ¤ ¥ ¥ £ ¡ ¡ ¢ 1961 | An enemy of the people !" " # $ % & ' ( ' ) % * ! + ,( - % 1959 | The crucible 14 PLAYBILL 3 ¡ ¤ £ ¤ ¦ § 4 £ ¦ ¦ § 5 . ¡ ¡ / ¤ 6 ¥ ¦ ¤ . ¢ ¤ ¤ ¥ ¤ ¦ 1 . ¤ 2 ¢ £ 1984 | All my sons 1989 | a view from the bridge 1994 | The crucible 1984 Miller’s play After The Fall is sometimes thought to have been inspired by his marriage to what popular Hollywood starlet? A. Marilyn Monroe B. Rita Hayworth Arthur Miller received the fi rst lifetime achievement C. Audrey Hepburn Alley Award in 1984 for “enduring contributions to the theatrical arts.” Pictured: Lois Stark, Lynn Wyatt, D. -

International Research Journal of Commerce, Arts and Science Issn 2319 – 9202

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMMERCE, ARTS AND SCIENCE ISSN 2319 – 9202 An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust WWW.CASIRJ.COM www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions CASIRJ Volume 9 Issue 2 [Year - 2018] ISSN 2319 – 9202 Reflection of a new society in the works of Arthur Miller Ojasavi Research Scholar Singhania University,Pacheri, Jhunjhunu Analysis of writings of Arthur Asher Miller is one of the land mark in English literature. It not only increase the analytical capacity of a scholar but add some information in existing literature which increase the curiosity of the reader in concerned subject and leads to origin of new ideas. The present research concentrates on critical analysis of selected writings of Arthur Asher Miller with emphasis on circumstances under which ideas came in the mind. Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist, and prominent figure in twentieth-century American theatre. Among his most popular plays are All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953) and A View from the Bridge (1955, revised 1956). He also wrote several screenplays and was most noted for his work on The Misfits (1961). The drama Death of a Salesman is often numbered on the short list of finest American plays in the 20th century alongside Long Day's Journey into Night and A Streetcar Named Desire. Before proceeding forward about writings of Miller it is necessary to know about his life and society when he came in to public eye, particularly during the late 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s. -

THE CRUCIBLE by Arthur Miller

THE CRUCIBLE by Arthur Miller THE AUTHOR Arthur Miller (1915-2005) was born and raised in New York City. He worked his way through college at the University of Michigan, and by the time he graduated in 1938, he had already received a number of awards for plays he wrote in his undergraduate years. After a number of early professional attempts that failed, he produced his first theatrical success with All My Sons in 1947. The play generally considered his masterpiece, The Death of a Salesman, won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1949 and catapulted him into the company of America’s greatest living playwrights. Other successes included The Crucible (1953), a drama about the Salem witch trials in which he reflected on the McCarthy era, A View from the Bridge (1955), After the Fall (1964), The Price (1968), The American Clock (1980), and Broken Glass (1995). He also wrote the script for the movie The Misfits (1961 - the script was written as a starring vehicle for his wife, Marilyn Monroe, but the two divorced shortly after the movie was produced) and the Emmy Award-winning television special Playing for Time (1980). The Crucible was written during the height of the McCarthy era, during which the House Un- American Activities Committee sought to root out communism from American politics and the media. Hollywood, always politically liberal, was a major target of McCarthy and his minions, and Miller was one of those called to testify before the committee (1956). As portrayed in the play, those who testified were pressured to give the names of any they knew who may have been tainted with the brush of communist ideology. -

Death of a Salesman. Inside This Guide

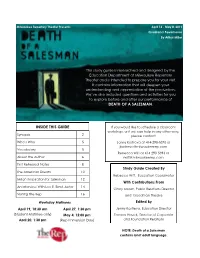

Milwaukee Repertory Theater Presents April 12 - May 8, 2011 Quadracci Powerhouse By Arthur Miller This study guide is researched and designed by the Education Department at Milwaukee Repertory Theater and is intended to prepare you for your visit. It contains information that will deepen your understanding and appreciation of the production. We‘ve also included questions and activities for you to explore before and after our performance of DEATH OF A SALESMAN. INSIDE THIS GUIDE If you would like to schedule a classroom workshop, or if we can help in any other way, Synopsis 2 please contact Who‘s Who 5 Jenny Kostreva at 414-290-5370 or [email protected] Vocabulary 5 Rebecca Witt at 414-290-5393 or About the Author 6 [email protected] First Rehearsal Notes 8 Study Guide Created By The American Dream 10 Rebecca Witt, Education Coordinator Miller‘s Inspiration for Salesman 12 With Contributions From An Interview With Lee E. Ernst, Actor 14 Cindy Moran, Public Relations Director Visiting The Rep 16 and Goodman Theatre Weekday Matinees Edited By April 19, 10:30 am April 27, 1:30 pm Jenny Kostreva, Education Director (Student Matinee only) May 4, 12:00 pm Tamara Hauck, Director of Corporate April 20, 1:30 pm (Rep Immersion Day) and Foundation Relations NOTE: Death of a Salesman contains brief adult language. Page 2 SYNOPSIS *Spoiler Alert: This synopsis contains crucial plot because Biff is well-liked and Bernard is not. points. After Bernard leaves, Willy and Linda discuss how much Willy made from sales. They realize All Costume Renderings were drawn by Rachel that it‘s not quite enough to pay the bills, but Healy, Costume Designer.