The Case of the Central African Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

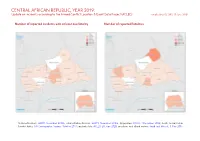

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 104 57 286 Conflict incidents by category 2 Strategic developments 71 0 0 Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 2 Battles 68 40 280 Protests 35 0 0 Methodology 3 Riots 19 4 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 2 2 3 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 299 103 573 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

East Area of Central African Republic : Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where (As of Janv 2018)

East area of Central African Republic : Who has a Sub-Office/Base where (as of janv 2018) [Country name]: [Subject] (as of XX Mmm YYYY) National NGO 30 Nord Soudan International NGO 24 Government 9 Birao UN 9 Vakaga Red Cross 2 UN : OCHA, WHO, UNHCR INGO : DCA, IMC, TGH Sud Soudan Movement INGO: COOPI, INVISIBLE RCM : CICR Tchad CHILDREN, IMC, MSF F, MAHDED, NDA LEGEND OXFAM NNGO: RCM : CRCA Ouanda-Djallé Limit of countries NNGO: ACACD, AFPE, APSUD, Limit of Prefectures Bria Londo, NNGO: NDA ESPERANCE, IDEAL, Limit of Sub-Prefecture MAHDED, NDA INGO : ACF, COHEB NNGO: MAHDED, UN : UN Agencies GOUV : AS Bamingui-Bangoran NDA INGO: International NGO NNGO: ACDES, AFJC, CARITAS, Red Cross Movement ESPERANCE RCM : Government INGO:ACF, Ouadda GOUV : ACTED, MC NNGO: National NGO Number of partners per locality Haute-Kotto Yalinga FAO, OCHA, UNDP, UNFPA, INGO: COHEB CRS UN : Nana-Gribizi INGO: 0 1-5 6-10 11-15 >=15 UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, WHO RCM : CRCA NNGO: MAHDED INGO : ACTED, AHA, AIRD, COHEB, COOPI, GOUV : AS OuhamDCA, HI, IMC, INSO, JRS, MC, MSF Bria Djéma H, RESCUE TEAM, TGH, WC UK Bakala RCM : CICR Bouca Ippy NNGO: CARITAS ACDA, ANDE, ANEA, AS, CNR, Ouaka Haut-Mbomou GOUV : DREH4, IACE, PSO NNGO: ACDES, AEPA, ACCES, APSUD, CARITAS, ESPERANCE, JUPEDEC, Bakouma Rafai Kémo Grimari LEVIER PLUS, NDA, NOURRIR, MTM, Bambari Mbomou ODESCA, REPROSEM INGO:CORDAID, Bambouti Obo CRS NNGO: CARITAS Zémio UN : OCHA, UNDP Mingala Kouango INGO:OmbellaACTED, M'Poko COHEB, COOPI, Basse-Kotto Bangassou Concern Alindao Gambo RCM : CRCA, CICR UN : UNHCR, UNDP -

1 FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain De Tension À Gambo, Ouango Et Bema

République Centrafricaine : Région : Est, Bambari Rapport hebdo de la situation n o 32 (13 Aout 2017) Ce rapport a été produit par OCHA en collaboration avec les partenaires humanitaires. Il a été publié par le Sous-bureau OCHA Bambari et couvre la période du 7 au 13 Aout 2017. Sur le plan géographique, il couvre les préfectures de la Ouaka, Basse Kotto, Haute Kotto, Mbomou, Haut-Mbomou et Vakaga. FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain de tension à Gambo, Ouango et Bema tous dans la préfecture de Mbomou : nécessité d’un renforcement de mécanisme de protection civile dans ces localités ; • Rupture en médicament au Centre de santé de Kembé face aux blessés de guerre enregistrés tous les jours dans cette structure sanitaire ; • Environ 77,59% de personnes sur 28351 habitants de Zémio se sont déplacées suite aux hostilités depuis le 28 juin. CONTEXTES SECURITAIRE ET HUMANITAIRE Haut-Mbomou La situation sécurité est demeurée fragile cette semaine avec la persistance des menaces d’incursion des groupes armés dans la ville. Ces menaces Le 10 août, un infirmier secouriste a été tué par des présumés sujets musulmans dans le quartier Ayem, dans le Sud-Ouest de la ville. Les circonstances de cette exécution restent imprécises. Cet incident illustre combien les défis de protection dans cette ville nécessitent un suivi rapproché. Mbomou Les affrontements de la ville de Bangassou sont en train de connaitre un glissement vers les autres sous-préfectures voisines telles Gambo, Ouango et Béma. En effet, depuis le 03 aout les heurts se sont produits entre les groupes armés protagonistes à Gambo, localité située à 75 km de Bangassou sur l’axe Bangassou-Kembé-Alindao-Bambari. -

CMP Juin 2020 STATISTIQUES DETAILLEES DES SITES Pdis EN

Legende CMP Juin 2020 Type-site: En hausse Update S= site Stable STATISTIQUES DETAILLEES DES SITES PDIs EN RCA L= Lieu de Regroupement En baisse No Update Differe # Préfecture Sous-Préfecture Commune Localité Site Type-site 31.05.2020 30.06.2020 Evolution Date Update Update Commentaires Sources de Donnees nce 1 Haut-Mbomou Zemio Zemio Zemio Site D L 2771 2853 3% juin-20 Profilage DTM IOM 205 PDIs venant de l'axe Bambouti suite aux exactions des 2 Haut-Mbomou Obo Obo Obo Gougbere S 2410 2410 0% Novembre 2019 ASA elements armes assimiles a l'UPC 3 Haut-Mbomou Obo Obo Obo Ligoua S 1180 1180 0% Juin 2019 COOPI 4 Haut-Mbomou Obo Obo Obo Nguilinguili S 455 455 0% Juin 2019 COOPI 5 Haut-Mbomou Obo Obo Obo Zemio S 693 693 0% Mars 2020 Profilage DTM IOM 6 Haut-Mbomou Obo Obo Mboki Mboki S 1579 2889 83% juin-20 Des PDIs venus de Obo entre Mai et juin Mission InterAgence 7 Haut-Mbomou Obo Obo Obo Catolique L 300 400 33% juin-20 Informateur clef le Prete de l'Eglise Catholique CCCM 8 Haut-Mbomou Djemah Djemah Kadjima A1 L 610 610 0% Mars 2020 Profilage DTM IOM 9 Haut-Mbomou Djemah Djemah Kadjima A2 L 625 625 0% Mars 2020 Profilage DTM IOM 10 Haut-Mbomou Djemah Djemah Kadjima B1 L 640 640 0% Mars 2020 Profilage DTM IOM 11 Haut-Mbomou Djemah Djemah Kadjima B2 L 675 675 0% Mars 2020 Profilage DTM IOM 12 Haut-Mbomou Djemah Djemah Kadjima C1 L 1085 1085 0% Mars 2020 Profilage DTM IOM Site catholique Petit ASA-Profilage 13 Mbomou Bangassou Bangassou Bangassou S 2012 2052 2% juin-20 ASA Seminaire 14 Mbomou Rafaï Rafaï AIM Site Aim S 185 185 0% Mai 2020 -

Central Africa | 53

CENTRAL AFRICA | 53 3.3 Mission Reviews Central Africa ith 30 countries in Africa expected to hold W elections in 2011, the year promises to be one of transition for the continent. Virtually all Central African states already have held or are scheduled to hold elections in the near future. Following Burundi’s polls in June 2010, the Central African Republic (CAR) and Chad conducted their highly anticipated elections in early 2011. While international observers described the electoral processes in all three countries as chaotic and marred by irregularities – including boycotts by opposition parties, these occurrences were not severe enough to invalidate the results. Notwithstanding the elections’ shortcom- UN Photo/ BINUCA ings, their largely peaceful conduct and the general Former BINUCA SRSG Sahle-Work Zewde meets with members of the Armée acceptance of results constitute significant achieve- populaire pour la restauration de la démocratie (APRD) in the Central Africa ments given the still recent history of democratic Republic, July 2010. transition in the region. Countries in the sub- region continue to face considerable challenges the elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo that threaten peace and hinder social and economic (DRC) scheduled for November this year, the gov- development, however. These include widespread ernment is likely to intensify its call for an end to poverty, weak governments, endemic corruption MONUSCO’s mandate – the last remaining large- and precarious security situations heightened by scale peacekeeping operation in the region.1 Given armed groups that use the countries porous borders regional dynamics in the DRC conflict, scaling to move freely and conduct acts of violence across down the UN’s political and military presence in the region. -

La Pratique De L'éducation Physique Et Sportive En Milieu Scolaire Centrafricain : Cas Du Lycée Barthélémy Boganda De Bang

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR, DES UNIVERSITES, DES CENTRES UNIVERSITAIRES REGIONAUX ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UINVERSITE CHEIKH ANTA DIOP DE DAKAR INSTITUT NATIONAL SUPERIEUR DE L’EDUCATION POPULAIRE ET DU SPORT (INSEPS) Monographie pour l’obtention du certificat d’aptitude aux fonctions d’inspecteur de l’éducation populaire, de la jeunesse et des sports. THEME LA PRATIQUE DE L’EDUCATION PHYSIQUE ET SPORTIVE EN MILIEU SCOLAIRE CENTRAFRICAIN : CAS DU LYCEE BARTHELEMY BOGANDA DE BANGUI (RCA) Présentée par : Sous la direction de : Mr. CHRISOSTOME R.OUAPORO Mr. MBAYE DIONE j Promotion: 2010-2012 DEDICACES Je dédie ce travail : à DIEU Tout puissant, le miséricordieux Que ta grâce bienveillante nous fasse voir en ceux qui souffrent, rien que des êtres à secourir. A mes parents, qui ne sont plus de ce monde ; FEU : OUAPORO PIERRE FEUE : NDAMATCHI ANDRIENNE Vous qui avez voulu me faire confiance, vous qui êtes voués corps et âme à mon éducation, bien qu’étant absents, recevez mes reconnaissances, à DIEU que vos âmes se reposent en paix. A mes sœurs et frères bien aimés ; Plus particulièrement à mon grand frère : OUAPORO GASPARD, pour son soutien indéfectible et incommensurable, que DIEU Tout puissant notre Seigneur lui donne le centuple et lui accorde sa bénédiction. Mes reconnaissances, à mon épouse chérie bien aimée ; Madame OUAPORO née : BAMBARY Sylvie Lucas Tu as accepté mes longues absences et partagé les peines avec tes enfants et que DIEU te comble de sa grâce. A nos enfants OUAPORO Dieu Béni OUAPORO-NDAMATCHI Jennifer OUAPORO Steffi OUAPORO Yann OUAPORO Kathleen OUAPORO Petit Pierre OUAPORO Mélissa Mon neveu ; KANGABET Gaspard i A mes sœurs ; Feue : OUAPORO Mélanie, paix à son âme. -

Pdf | 1006.42 Kb

Bulletin humanitaire République centrafricaine Numéro 49 | Novembre 2019 Au sommaire P. 1 Intensification de l’aide humanitaire dans les zones Inaccessibles P.3 Inondations FAITS SAILLANTS P.4 Les efforts de la communauté humanitaire commencent • 272 incidents touchant directement à porter leurs fruits à Zémio le personnel ou les biens P.6 La voix du Pangolin humanitaires ont été enregistrés entre janvier et novembre 2019. P.7 Success Story Leurs conséquences sont sérieuses P.10 Le saviez-vous et privent des populations entières OCHA RCA/ Fabrice Gernigon d’assistance ; ainsi quatre organisations ont temporairement suspendu leurs actions humanitaires en octobre et novembre et 40 blessés ont été enregistrés parmi les humanitaires Intensification de l’aide humanitaire dans les durant ces onze derniers mois, contre 23 durant la même période zones les plus inaccessibles de la en 2018. • Un hélicoptère d'une capacité de 18 Centrafrique passagers et / ou 2,5 tonnes de fret a été mis à la disposition de la communauté humanitaire par le Un accès humanitaire qui reste extrêmement contraignant dans plusieurs sous- Service aérien d’aide humanitaire préfectures des Nations Unies (UNHAS). Sa mission consiste à desservir les Un des obstacles les plus complexes auxquels sont confrontés les humanitaires en zones touchées par les inondations ainsi que celles qui sont difficiles République centrafricaine est la difficulté d’accès aux personnes les plus vulnérables. d’accès. L’appareil a permis Nombreux sont celles et ceux qui présentent les besoins les plus aigus mais vivent dans d’assurer une bien meilleure des zones particulièrement isolées, du fait des contraintes sécuritaires, mais aussi des couverture des zones affectées par contraintes logistiques liées à la vétusté des infrastructures routières. -

Central African Republic

Central African Republic 14 December 2013 Prepared by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team PERIOD: SUMMARY 1 January – 31 December 2014 Strategic objectives 100% 1. Provide integrated life-saving assistance to people in need as a result of the continuing political and security crisis, particularly IDPs and their 4.6 million host communities. total population 2. Reinforce the protection of civilians, including of their fundamental human rights, in particular as it relates to women and children. 48% of total population 3. Rebuild affected communities‘ resilience to withstand shocks and 2.2 million address inter-religious and inter-community conflicts. estimated number of people in Priority actions need of humanitarian aid Rapidly scale up humanitarian response capacity, including through 43% of total population enhanced security management and strengthened common services 2.0 million (logistics including United Nations Humanitarian Air Service, and telecoms). people targeted for humanitarian Based on improved monitoring and assessment, cover basic, life- aid in this plan saving needs (food, water, hygiene and sanitation / WASH, health, nutrition and shelter/non-food items) of internally displaced people and Key categories of people in their host communities and respond rapidly to any new emergencies. need: Ensure availability of basic drugs and supplies at all clinics and internally 533,000 hospitals and rehabilitate those that have been destroyed or looted. 0.6 displaced Rapidly increase vaccine coverage, now insufficient, and ensure adequate million management of all cases of severe acute malnutrition. displaced 20,336 refugees Strengthen protection activities and the protection monitoring system 1.6 and facilitate engagement of community organizations in conflict resolution million and community reconciliation initiatives. -

Download CAR Civsoclettertousaid 2012 04.20 EN.Pdf

April 20, 2012 ATTN: Dr. Rajiv Shah, USAID Administrator, Washington, DC Copied: USAID Representative in the Central African Republic, Bangui Subject: Insecurity in Mbomou and Haut-Mbomou Prefectures, CAR We, civil society organizations of the Central African Republic, write to USAID to present our request regarding the security, sociopolitical, and economic situation in Mbomou and Haut- Mbomou prefectures. The region comprising Mbomou and Haut-Mbomou prefectures, in southeastern CAR, borders the Democratic Republic of Congo and is far from CAR’s capital, Bangui. This region has experienced a multi-sectorial crisis for a decade, with growing insecurity due to the presence of the Lord’s Resistance Army. This uncontrolled force operates completely undisturbed, preying on peaceful citizens. From one day to the next, we record cases of rape, looting, burning of villages, killings and murders, kidnapping of adults and children, forced recruitment of children into the LRA, and more. Following abuses by men loyal to Joseph Kony, the LRA leader, parts of the two prefectures have become inaccessible. Indeed, in a recent joint declaration by civil society organizations from DRC and CAR, a “Call for Solidarity,” signatories alluded to the region’s isolation, a factor Joseph Kony exploits to do as he pleases and remain elusive. In order to help save lives in a community nearing collapse after attacks by LRA troops, we hope that certain proposals by civil society actors would be indispensable, in addition to the current emergency humanitarian actions. Desirable actions include: - Rehabilitation and re-opening of road sections: Bambouti – Bangassou traveling through Obo – Mboki – Zemio – Rafaï Zemio – Djemah and Obo – Djemah Djemah – Dembia - Installation of modern mobile telephone networks in the area, covering Djemah, Zemio, Mboki, and Rafai. -

Central African Republic 2012 As of 15 November 2011

SAMPLE OF ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEALS AARREC CRS Humedica TGH ACF CWS IA MENTOR UMCOR ACTED DanChurchAid ILO MERLIN UNAIDS ADRA DDG IMC Muslim Aid UNDP Africare DiakonieEmerg. Aid INTERMON NCA UNDSS PU-AMI DRC Internews NPA UNEP ARC EM-DH INTERSOS NRC UNESCO ASB FAO IOM OCHA UNFPA ASI FAR IPHD OHCHR UN-HABITAT AVSI FHI IR OXFAM UNHCR CARE FinnChurchAid IRC PA UNICEF CARITAS FSD IRD PACT UNIFEM CEMIR International GAA IRIN PAI UNJLC CESVI GOAL IRW Plan UNMAS CFA GTZ Islamic Relief PMU-I UNOPS CHF GVC JOIN RC/Germany UNRWA CHFI Handicap International JRS RCO VIS CISV HealthNet TPO LWF Samaritan's Purse WFP CMA HELP Malaria Consortium Save the Children WHO CONCERN HelpAge International Malteser SECADEV World Concern COOPI HKI Mercy Corps Solidarités World Relief CORDAID Horn Relief MDA SUDO WV COSV HT MDM TEARFUND ZOA MEDAIR Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 Humanitarian Dashboard ................................................................................................................ 3 Table I. Requirements per cluster .......................................................................................... 6 Table II. Requirements per priority level ................................................................................ 6 Table III. Requirements per organization ................................................................................ 7 2. 2011 IN REVIEW ..........................................................................................................................