Quotas for Leopard Hunting Trophies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinko/Mbari Drainage Basin Represents a Conservation Hotspot for Eastern Derby Eland in Central Africa

Published in "African Journal of Ecology 56 (2): 194–201, 2018" which should be cited to refer to this work. Chinko/Mbari drainage basin represents a conservation hotspot for Eastern Derby eland in Central Africa Karolına Brandlova1 | Marketa Glonekova1 | Pavla Hejcmanova1 | Pavla Jůnkova Vymyslicka1 | Thierry Aebischer2 | Raffael Hickisch3 | David Mallon4 1Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Praha 6, Abstract Czech Republic One of the largest of antelopes, Derby eland (Taurotragus derbianus), is an important 2Department of Biology, University of ecosystem component of African savannah. While the western subspecies is Critically Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland 3Chinko Project, Operations, Chinko, Endangered, the eastern subspecies is classified as least concern. Our study presents the Bangui, Central African Republic first investigation of population dynamics of the Derby eland in the Chinko/Mbari Drai- 4 Co-Chair, IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist nage Basin, Central African Republic, and assesses the conservation role of this popula- Group and Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, Manchester tion. We analysed data from 63 camera traps installed in 2012. The number of individuals Metropolitan University, Glossop, UK captured within a single camera event ranged from one to 41. Herds were mostly mixed Correspondence by age and sex, mean group size was 5.61, larger during the dry season. Adult (AD) males ı Karol na Brandlova constituted only 20% of solitary individuals. The overall sex ratio (M:F) was 1:1.33, while Email: [email protected] the AD sex ratio shifted to 1:1.52, reflecting selective hunting pressure. Mean density Funding information ranged from 0.04 to 0.16 individuals/km2, giving an estimated population size of 445– Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Grant/Award Number: 20135010, 1,760 individuals. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Fitzhenry Yields 2016.Pdf

Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii GENERAL ABSTRACT Fallow deer (Dama dama), although not native to South Africa, are abundant in the country and could contribute to domestic food security and economic stability. Nonetheless, this wild ungulate remains overlooked as a protein source and no information exists on their production potential and meat quality in South Africa. The aim of this study was thus to determine the carcass characteristics, meat- and offal-yields, and the physical- and chemical-meat quality attributes of wild fallow deer harvested in South Africa. Gender was considered as a main effect when determining carcass characteristics and yields, while both gender and muscle were considered as main effects in the determination of physical and chemical meat quality attributes. Live weights, warm carcass weights and cold carcass weights were higher (p < 0.05) in male fallow deer (47.4 kg, 29.6 kg, 29.2 kg, respectively) compared with females (41.9 kg, 25.2 kg, 24.7 kg, respectively), as well as in pregnant females (47.5 kg, 28.7 kg, 28.2 kg, respectively) compared with non- pregnant females (32.5 kg, 19.7 kg, 19.3 kg, respectively). -

Benefits-Of-Regulated-Hunting-For-Leopard

CONSERVATION FORCE A FORCE FOR WILDLIFE CONSERVATION BENEFITS OF REGULATED HUNTING FOR LEOPARD (PANTHERA PARDUS) Legal, regulated tourist hunting of African leopard (Panthera pardus) benefits the species through mitigation of the primary threats: habitat loss and fragmentation; increased human populations leading to higher incidence of human-wildlife conflict; poaching and illegal wildlife trade; and prey base declines.i • Habitat: The threat of habitat loss is mitigated in part by fully-protected national parks, which provide over 400,000 km2 of relatively secure habitat for leopard across the six Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries that rely on regulated hunting to sustain their leopard and leopard prey populations.ii The national parks are > 30,000 km2 larger than in 1982, when the leopard was downlisted to “threatened” under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and leopard are estimated to be present in most of the parks in Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.iii Regulated hunting revenues help cover the costs of policing these parks, which in most cases do not generate sufficient revenue to cover all enforcement expenses.iv • Habitat: The threat of habitat loss is further mitigated by areas dedicated to regulated hunting. In Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, hunting areas include government reserves, communal wildlife management areas, and private ranches. They are substantially larger than the national parks and represent over 700,000 km2.v Leopard are estimated to be present across almost all hunting areas.vi • Habitat: According to the 2016 IUCN Red List assessment of leopard, the species’ total extant range exceeds 8.5 million km2, with between 4.3 million and 6.3 million km2 of range available in Southern and East Africa. -

African Parks 2 African Parks

African Parks 2 African Parks African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the total responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities. By adopting a business approach to conservation, supported by donor funding, we aim to rehabilitate each park making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable in the long-term. Founded in 2000, African Parks currently has 15 parks under management in nine countries – Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia. More than 10.5 million hectares are under our protection. We also maintain a strong focus on economic development and poverty alleviation in neighbouring communities, ensuring that they benefit from the park’s existence. Our goal is to manage 20 parks by 2020, and because of the geographic spread and representation of different ecosystems, this will be the largest and the most ecologically diverse portfolio of parks under management by any one organisation across Africa. Black lechwe in Bangweulu Wetlands in Zambia © Lorenz Fischer The Challenge The world’s wild and functioning ecosystems are fundamental to the survival of both people and wildlife. We are in the midst of a global conservation crisis resulting in the catastrophic loss of wildlife and wild places. Protected areas are facing a critical period where the number of well-managed parks is fast declining, and many are simply ‘paper parks’ – they exist on maps but in reality have disappeared. The driving forces of this conservation crisis is the human demand for: 1. -

African Mammals (Tracks)

L Gi'. M MM S C A POCKET NATURALISru GUIDE HOOFED MAMMALS Dik-Dik Madoqua spp . To 17 in. (43 cm) H Small antelope has a long, flexible snout. .,9-10 in. Common Hippopotamus Klipspringer Hippopotamus amphibius Oreatragus oreotroqus To 5 ft. (1.5 m) H To 2 ft. (60 cm) H Has dark 'tear stains' at the corner of the eyes. Downward-pointing hooves give the impression it walks on 'tiptoe'. Found in rocky habitats. White Black Steenbok Raphieerus eampestris 1 in. White Rhinoceros To 2 ft. (60 cm) H Large ears are striped inside. Ceratotherium simum Muzzle has a dark stripe. To 6 ft. (l.B m) H 9-10 in. t Has a square upper lip. The similar black rhinoceros has a , pointed, prehensile upper lip. t . eWhite '~'rBlack . Common Duiker " . Sylvieapra grimmia ". To 28 in. (70 cm) t1 t Has a prominent black 1 in. 'a: stripe on its snout. Inhabits woodlands Hyena lion and shrubby areas. t Forefoot , e+ Oribi 24-28 in. Ourebia ourebi African Elephant To 2 ft. (60 em) H Note short tail and black 1.5 in. Loxodonto africana Hind foot spot below ears. Inhabits To 14 ft. (4.2 m) H grassland savannas. Hind print is oval-shaped. t This guide provides simplified field reference to familiar animal tracks. It is important to note that tracks change depending on their age, the surface Hippopotamus they are made on, and the animal's gait (e.g., toes are often splayed when Springbok running). Track illustrations are ordered by size in each section and are not Antidorcas marsupialis To 30 in. -

Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa's Sudano-Sahel

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa’s Sudano-Sahel The interface of conservation, security, and development Mbororo pastoralists illegally grazing cattle in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Credit: Naftali Honig/African Parks Africa’s Sudano-Sahel is a distinct bioclimatic and ecological zone made up of savanna and savanna-forest transition Program Priorities habitat that covers approximately 7.7 million square kilometers of the continent. Rich in species diversity, the • Increased data gathering and assessment of core Sudano-Sahel region represents one of the last remaining natural resource assets across the Sudano-Sahel region. intact wilderness areas in the world, and is a high priority • Efficient data-sharing, analysis, and dissemination for wildlife conservation. It is home to an array of antelope between relevant stakeholders spanning conservation, species such as giant eland and greater kudu, in addition to security, and development sectors, and in collaboration African wild dog, Kordofan giraffe, African elephant, African with rural agriculturalists and pastoralists. lion, leopard, and giant pangolin. • Enhancement and promotion of multi-level This region is also home to many rural communities who rely governance approaches to resolve conflict and stabilize on the landscape’s natural resources, including pastoralists, transhumance corridors. whose livelihoods and cultural identity are centered around • Continuation and expansion of strategic investments in strategic mobility to access seasonally available grazing the network of priority protected areas and their buffer resources and water. Instability, climate change, and zones across the Sudano-Sahel, in order to improve increasing pressures from unsustainable land use activities security for both wildlife and surrounding communities. -

Big Cats in Africa Factsheet

INFORMATION BRIEF BIG CATS IN AFRICA AFRICAN LION (PANTHERA LEO) Famously known as the king of the jungle, the African lion is the second largest living species of the big cats, after the tiger. African lions are found mostly in savannah grasslands across many parts of sub-Saharan Africa but the “Babary lion” used to exist in the North of Africa including Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria, while the “Cape lion” existed in South Africa. Some lions have however been known to live in forests in Congo, Gabon or Ethiopia. Historically, lions used to live in the Mediterranean and the Middle East as well as in other parts of Asia such as India. While there are still some Asian Lions left in India, the African Lion is probably the largest remaining sub species of Lions in the world. They live in large groups called “prides”, usually made up of up to 15 lions. These prides consist of one or two males, and the rest females. The females are known for hunting for prey ranging from wildebeest, giraffe, impala, zebra, buffalo, rhinos, hippos, among others. The males are unique in appearance with the conspicuous mane around their necks. The mane is used for protection and intimidation during fights. Lions mate all year round, and the female gives birth to three or four cubs at a time, after a gestation period of close to 4 months (110 days). Lions are mainly threatened by hunting and persecution by humans. They are considered a threat to livestock, so ranchers usually shoot them or poison carcasses to keep them away from their livestock. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

Chapter 2 Transboundary Environmental Issues

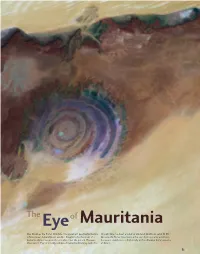

The Eyeof Mauritania Also known as the Richat Structure, this prominent geographic feature through time, has been eroded by wind and windblown sand. At 50 in Mauritania’s Sahara Desert was fi rst thought to be the result of a km wide, the Richat Structure can be seen from space by astronauts meteorite impact because of its circular, crater-like pattern. However, because it stands out so dramatically in the otherwise barren expanse Mauritania’s “Eye” is actually a dome of layered sedimentary rock that, of desert. Source: NASA Source: 37 ey/Flickr.com A man singing by himself on the Jemaa Fna Square, Morocco Charles Roff 38 Chapter2 Transboundary Environmental Issues " " Algiers Tunis TUNISIA " Rabat " Tripoli MOROCCO " Cairo ALGERIA LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA EGYPT WESTERN SAHARA MAURITANIA " Nouakchott CAPE VERDE MALI NIGER CHAD Khartoum " ERITREA " " Dakar Asmara Praia " SENEGAL Banjul Niamey SUDAN GAMBIA " " Bamako " Ouagadougou " Ndjamena " " Bissau DJIBOUTI BURKINA FASO " Djibouti GUINEA Conakry NIGERIA GUINEA-BISSAU " ETHIOPIA " " Freetown " Abuja Addis Ababa COTE D’IVORE BENIN LIBERIA TOGO GHANA " " CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SIERRA LEONE " Yamoussoukro " IA Accra Porto Novo L Monrovia " Lome A CAMEROON OM Bangui" S Malabo Yaounde " " EQUATORIAL GUINEA Mogadishu " UGANDA SAO TOME Kampala AND PRINCIPE " " Libreville " KENYA Sao Tome Nairobi GABON " Kigali CONGO " DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC RWANDA OF THE CONGO " Bujumbura Brazzaville BURUNDI "" Kinshasa UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA " Dodoma SEYCHELLES " Luanda Moroni " COMOROS Across Country Borders ANGOLA Lilongwe " MALAWI ZAMBIA Politically, the African continent is divided into 53 countries " Lusaka UE BIQ and one “non-self-governing territory.” Ecologically, Harare M " A Z O M Antananarivo" Port Louis Africa is home to eight major biomes— large and distinct ZIMBABWE " biotic communities— whose characteristic assemblages MAURITIUS Windhoek " BOTSWANA MADAGASCAR of fl ora and fauna are in many cases transboundary in NAMIBIA Gaborone " Maputo nature, in that they cross political borders. -

For Review Only 440 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group

Manuscripts submitted to Journal of Mammalogy A Pliocene hybridisation event reconciles incongruent mitochondrial and nuclear gene trees among spiral-horned antelopes Journal:For Journal Review of Mammalogy Only Manuscript ID Draft Manuscript Type: Feature Article Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Rakotoarivelo, Andrinajoro; University of Venda, Department of Zoology O'Donoghue, Paul; Specialist Wildlife Services, Specialist Wildlife Services Bruford, Michael; Cardiff University, Cardiff School of Biosciences Moodley, Yoshan; University of Venda, Department of Zoology adaptive radiation, interspecific hybridisation, paleoclimate, Sub-Saharan Keywords: Africa, Tragelaphus https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jmamm Page 1 of 34 Manuscripts submitted to Journal of Mammalogy 1 Yoshan Moodley, Department of Zoology, University of Venda, 2 [email protected] 3 Interspecific hybridization in Tragelaphus 4 A Pliocene hybridisation event reconciles incongruent mitochondrial and nuclear gene 5 trees among spiral-horned antelopes 6 ANDRINAJORO R. RAKATOARIVELO, PAUL O’DONOGHUE, MICHAEL W. BRUFORD, AND * 7 YOSHAN MOODLEY 8 Department of Zoology, University of Venda, University Road, Thohoyandou 0950, Republic 9 of South Africa (ARR, ForYM) Review Only 10 Specialist Wildlife Services, 102 Bowen Court, St Asaph, LL17 0JE, United Kingdom (PO) 11 Cardiff School of Biosciences, Sir Martin Evans Building, Cardiff University, Museum 12 Avenue, Cardiff, CF10 3AX, United Kingdom (MWB) 13 Natiora Ahy Madagasikara, Lot IIU57K Bis, Ampahibe, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar 14 (ARR) 15 16 1 https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jmamm Manuscripts submitted to Journal of Mammalogy Page 2 of 34 17 ABSTRACT 18 The spiral-horned antelopes (Genus Tragelaphus) are among the most phenotypically diverse 19 of all large mammals, and evolved in Africa during an adaptive radiation that began in the late 20 Miocene, around 6 million years ago.