Central Africa | 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

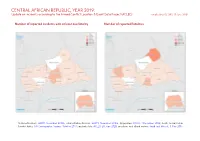

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 104 57 286 Conflict incidents by category 2 Strategic developments 71 0 0 Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 2 Battles 68 40 280 Protests 35 0 0 Methodology 3 Riots 19 4 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 2 2 3 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 299 103 573 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

East Area of Central African Republic : Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where (As of Janv 2018)

East area of Central African Republic : Who has a Sub-Office/Base where (as of janv 2018) [Country name]: [Subject] (as of XX Mmm YYYY) National NGO 30 Nord Soudan International NGO 24 Government 9 Birao UN 9 Vakaga Red Cross 2 UN : OCHA, WHO, UNHCR INGO : DCA, IMC, TGH Sud Soudan Movement INGO: COOPI, INVISIBLE RCM : CICR Tchad CHILDREN, IMC, MSF F, MAHDED, NDA LEGEND OXFAM NNGO: RCM : CRCA Ouanda-Djallé Limit of countries NNGO: ACACD, AFPE, APSUD, Limit of Prefectures Bria Londo, NNGO: NDA ESPERANCE, IDEAL, Limit of Sub-Prefecture MAHDED, NDA INGO : ACF, COHEB NNGO: MAHDED, UN : UN Agencies GOUV : AS Bamingui-Bangoran NDA INGO: International NGO NNGO: ACDES, AFJC, CARITAS, Red Cross Movement ESPERANCE RCM : Government INGO:ACF, Ouadda GOUV : ACTED, MC NNGO: National NGO Number of partners per locality Haute-Kotto Yalinga FAO, OCHA, UNDP, UNFPA, INGO: COHEB CRS UN : Nana-Gribizi INGO: 0 1-5 6-10 11-15 >=15 UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, WHO RCM : CRCA NNGO: MAHDED INGO : ACTED, AHA, AIRD, COHEB, COOPI, GOUV : AS OuhamDCA, HI, IMC, INSO, JRS, MC, MSF Bria Djéma H, RESCUE TEAM, TGH, WC UK Bakala RCM : CICR Bouca Ippy NNGO: CARITAS ACDA, ANDE, ANEA, AS, CNR, Ouaka Haut-Mbomou GOUV : DREH4, IACE, PSO NNGO: ACDES, AEPA, ACCES, APSUD, CARITAS, ESPERANCE, JUPEDEC, Bakouma Rafai Kémo Grimari LEVIER PLUS, NDA, NOURRIR, MTM, Bambari Mbomou ODESCA, REPROSEM INGO:CORDAID, Bambouti Obo CRS NNGO: CARITAS Zémio UN : OCHA, UNDP Mingala Kouango INGO:OmbellaACTED, M'Poko COHEB, COOPI, Basse-Kotto Bangassou Concern Alindao Gambo RCM : CRCA, CICR UN : UNHCR, UNDP -

1 FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain De Tension À Gambo, Ouango Et Bema

République Centrafricaine : Région : Est, Bambari Rapport hebdo de la situation n o 32 (13 Aout 2017) Ce rapport a été produit par OCHA en collaboration avec les partenaires humanitaires. Il a été publié par le Sous-bureau OCHA Bambari et couvre la période du 7 au 13 Aout 2017. Sur le plan géographique, il couvre les préfectures de la Ouaka, Basse Kotto, Haute Kotto, Mbomou, Haut-Mbomou et Vakaga. FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain de tension à Gambo, Ouango et Bema tous dans la préfecture de Mbomou : nécessité d’un renforcement de mécanisme de protection civile dans ces localités ; • Rupture en médicament au Centre de santé de Kembé face aux blessés de guerre enregistrés tous les jours dans cette structure sanitaire ; • Environ 77,59% de personnes sur 28351 habitants de Zémio se sont déplacées suite aux hostilités depuis le 28 juin. CONTEXTES SECURITAIRE ET HUMANITAIRE Haut-Mbomou La situation sécurité est demeurée fragile cette semaine avec la persistance des menaces d’incursion des groupes armés dans la ville. Ces menaces Le 10 août, un infirmier secouriste a été tué par des présumés sujets musulmans dans le quartier Ayem, dans le Sud-Ouest de la ville. Les circonstances de cette exécution restent imprécises. Cet incident illustre combien les défis de protection dans cette ville nécessitent un suivi rapproché. Mbomou Les affrontements de la ville de Bangassou sont en train de connaitre un glissement vers les autres sous-préfectures voisines telles Gambo, Ouango et Béma. En effet, depuis le 03 aout les heurts se sont produits entre les groupes armés protagonistes à Gambo, localité située à 75 km de Bangassou sur l’axe Bangassou-Kembé-Alindao-Bambari. -

La Pratique De L'éducation Physique Et Sportive En Milieu Scolaire Centrafricain : Cas Du Lycée Barthélémy Boganda De Bang

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR, DES UNIVERSITES, DES CENTRES UNIVERSITAIRES REGIONAUX ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UINVERSITE CHEIKH ANTA DIOP DE DAKAR INSTITUT NATIONAL SUPERIEUR DE L’EDUCATION POPULAIRE ET DU SPORT (INSEPS) Monographie pour l’obtention du certificat d’aptitude aux fonctions d’inspecteur de l’éducation populaire, de la jeunesse et des sports. THEME LA PRATIQUE DE L’EDUCATION PHYSIQUE ET SPORTIVE EN MILIEU SCOLAIRE CENTRAFRICAIN : CAS DU LYCEE BARTHELEMY BOGANDA DE BANGUI (RCA) Présentée par : Sous la direction de : Mr. CHRISOSTOME R.OUAPORO Mr. MBAYE DIONE j Promotion: 2010-2012 DEDICACES Je dédie ce travail : à DIEU Tout puissant, le miséricordieux Que ta grâce bienveillante nous fasse voir en ceux qui souffrent, rien que des êtres à secourir. A mes parents, qui ne sont plus de ce monde ; FEU : OUAPORO PIERRE FEUE : NDAMATCHI ANDRIENNE Vous qui avez voulu me faire confiance, vous qui êtes voués corps et âme à mon éducation, bien qu’étant absents, recevez mes reconnaissances, à DIEU que vos âmes se reposent en paix. A mes sœurs et frères bien aimés ; Plus particulièrement à mon grand frère : OUAPORO GASPARD, pour son soutien indéfectible et incommensurable, que DIEU Tout puissant notre Seigneur lui donne le centuple et lui accorde sa bénédiction. Mes reconnaissances, à mon épouse chérie bien aimée ; Madame OUAPORO née : BAMBARY Sylvie Lucas Tu as accepté mes longues absences et partagé les peines avec tes enfants et que DIEU te comble de sa grâce. A nos enfants OUAPORO Dieu Béni OUAPORO-NDAMATCHI Jennifer OUAPORO Steffi OUAPORO Yann OUAPORO Kathleen OUAPORO Petit Pierre OUAPORO Mélissa Mon neveu ; KANGABET Gaspard i A mes sœurs ; Feue : OUAPORO Mélanie, paix à son âme. -

Pdf | 1006.42 Kb

Bulletin humanitaire République centrafricaine Numéro 49 | Novembre 2019 Au sommaire P. 1 Intensification de l’aide humanitaire dans les zones Inaccessibles P.3 Inondations FAITS SAILLANTS P.4 Les efforts de la communauté humanitaire commencent • 272 incidents touchant directement à porter leurs fruits à Zémio le personnel ou les biens P.6 La voix du Pangolin humanitaires ont été enregistrés entre janvier et novembre 2019. P.7 Success Story Leurs conséquences sont sérieuses P.10 Le saviez-vous et privent des populations entières OCHA RCA/ Fabrice Gernigon d’assistance ; ainsi quatre organisations ont temporairement suspendu leurs actions humanitaires en octobre et novembre et 40 blessés ont été enregistrés parmi les humanitaires Intensification de l’aide humanitaire dans les durant ces onze derniers mois, contre 23 durant la même période zones les plus inaccessibles de la en 2018. • Un hélicoptère d'une capacité de 18 Centrafrique passagers et / ou 2,5 tonnes de fret a été mis à la disposition de la communauté humanitaire par le Un accès humanitaire qui reste extrêmement contraignant dans plusieurs sous- Service aérien d’aide humanitaire préfectures des Nations Unies (UNHAS). Sa mission consiste à desservir les Un des obstacles les plus complexes auxquels sont confrontés les humanitaires en zones touchées par les inondations ainsi que celles qui sont difficiles République centrafricaine est la difficulté d’accès aux personnes les plus vulnérables. d’accès. L’appareil a permis Nombreux sont celles et ceux qui présentent les besoins les plus aigus mais vivent dans d’assurer une bien meilleure des zones particulièrement isolées, du fait des contraintes sécuritaires, mais aussi des couverture des zones affectées par contraintes logistiques liées à la vétusté des infrastructures routières. -

Central African Republic

Central African Republic 14 December 2013 Prepared by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team PERIOD: SUMMARY 1 January – 31 December 2014 Strategic objectives 100% 1. Provide integrated life-saving assistance to people in need as a result of the continuing political and security crisis, particularly IDPs and their 4.6 million host communities. total population 2. Reinforce the protection of civilians, including of their fundamental human rights, in particular as it relates to women and children. 48% of total population 3. Rebuild affected communities‘ resilience to withstand shocks and 2.2 million address inter-religious and inter-community conflicts. estimated number of people in Priority actions need of humanitarian aid Rapidly scale up humanitarian response capacity, including through 43% of total population enhanced security management and strengthened common services 2.0 million (logistics including United Nations Humanitarian Air Service, and telecoms). people targeted for humanitarian Based on improved monitoring and assessment, cover basic, life- aid in this plan saving needs (food, water, hygiene and sanitation / WASH, health, nutrition and shelter/non-food items) of internally displaced people and Key categories of people in their host communities and respond rapidly to any new emergencies. need: Ensure availability of basic drugs and supplies at all clinics and internally 533,000 hospitals and rehabilitate those that have been destroyed or looted. 0.6 displaced Rapidly increase vaccine coverage, now insufficient, and ensure adequate million management of all cases of severe acute malnutrition. displaced 20,336 refugees Strengthen protection activities and the protection monitoring system 1.6 and facilitate engagement of community organizations in conflict resolution million and community reconciliation initiatives. -

Failing to Prevent Atrocities in the Central African Republic

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect Occasional Paper Series No. 7, September 2015 Too little, too late: Failing to prevent atrocities in the Central African Republic Evan Cinq-Mars The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the “Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Through its programs and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is a resource for governments, international institutions and civil society on prevention and early action to halt mass atrocity crimes. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Occasional Paper was produced with the generous support of Humanity United. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Evan Cinq-Mars is an Advocacy Officer at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, where he monitors populations at risk of mass atrocities in Central African Republic (CAR), Burundi, Guinea and Mali. Evan also coordinates the Global Centre’s media strategy. Evan has undertaken two research missions to CAR since March 2014 to assess efforts to uphold the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). He has appeared as an expert commentator on the CAR situation on Al Jazeera and the BBC, and his analysis has appeared in Bloomberg, Foreign Policy, The Globe and Mail, Radio France International, TIME and VICE News. Evan was previously employed by the Centre for International Governance Innovation. He holds an M.A. in Global Governance, specializing in Conflict and Security, from the Balsillie School of International Affairs at the University of Waterloo. COVER PHOTO: Following a militia attack on a Fulani Muslim village, wounded children are watched over by Central African Republic soldiers in Bangui. -

The Case of the Central African Republic

The Extractive Industries and Society 1 (2014) 249–259 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Extractive Industries and Society jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/exis Original article A sub-national scale geospatial analysis of diamond deposit lootability: The case of the Central African Republic 1 Katherine C. Malpeli *, Peter G. Chirico U.S. Geological Survey, MS926A National Center, 12201 Sunrise Valley Drive, Reston, VA 20192, United States A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: The Central African Republic (CAR), a country with rich diamond deposits and a tumultuous political Received 2 May 2014 history, experienced a government takeover by the Seleka rebel coalition in 2013. It is within this context Received in revised form 28 July 2014 that we developed and implemented a geospatial approach for assessing the lootability of high value-to- Available online 23 August 2014 weight resource deposits, using the case of diamonds in CAR as an example. According to current definitions of lootability, or the vulnerability of deposits to exploitation, CAR’s two major diamond Keywords: deposits are similarly lootable. However, using this geospatial approach, we demonstrate that the Conflict diamonds deposits experience differing political geographic, spatial location, and cultural geographic contexts, Lootability rendering the eastern deposits more lootable than the western deposits. The patterns identified through Central African Republic this detailed analysis highlight the geographic complexities surrounding the issue of conflict resources and lootability, and speak to the importance of examining these topics at the sub-national scale, rather than relying on national-scale statistics. -

Operational Presence in BASSE KOTTO(3W:OP) August 2016

CAR: Operational Presence in BASSE KOTTO(3W:OP) August 2016 Organisations responding with By organisation type By cluster emergency programs 16 Protection 6 International NGO 5 WASH 3 Health National NGO 5 6 LCS 1 UN 4 Food Security 8 Red Cross Movement 2 Nutrition 3 Shelter & NFI 2 Education 1 CCCM 1 Logistics 1 CCCM Education Food Security 1 partner 1 partner 8 partners Shelter & NFI Emergency Telecom. Logistics 2 partners 0 partner 1 partner Health LCS WASH 6 partners 1 partner 3 partners Nutrition Protection 3 partners 6 partners Is your data missing from this document? Return it to [email protected] and your data will be on the next version. Thanks for helping out! Updated: 31 Août 2016 Source: Clusters and Partners Suggestions: [email protected]/ [email protected] More information: http://car.humanitarianresponse.info/ Designations and geography used on these maps does not imply endorsement by the United Nations CAR: Operational Presence in BASSE KOTTO(3W:OP) August 2016 16 Partners Presence 5 International NGO 5 National NGO 4 UN Agencies 2 Red Cross Movement REMOD, FAO UNICEF LEGEND WHO WFP, COHEB, CADAPI, FAO Sectors Coordination CORDAID , WHO, UNICEF Education CORDAID, UNICEF Food Security CICR, UNICEF Health Logistics UNICEF, ACTED, CORDAID Nutrition ACTED Mingala Protection ACTED Shelter and NFI Telecommunication WASH FAO, CADAPI Alindao CCCM WHO, MSF E LCS MSF E Zangba Kembé Mobaye Satéma UNICEF ACTED, VITALITE+, FAO, ACDES, COHEB, CADAPI, REMOD WHO, SCI, UNICEF, CRCA CADAPI, FAO, COHEB, ACTED WHO UNICEF, ACDES, CICR, VITALITE+, -

An Uncertain Future? Children and Armed Conflict in the Central African Republic

an uncertain future? Children and Armed Conflict in the Central African Republic May 2011 About Watchlist The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict (Watchlist) strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, the Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national, and international non-govern- mental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, please contact: [email protected] / www.watchlist.org About IDMC The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) was established by the Norwegian Refugee Council in 1998, upon the request of the United Nations, to set up a global database on internal displacement. A decade later, IDMC remains the leading source of information and analysis on internal displacement caused by conflict and violence worldwide. IDMC’s main activities include monitoring and reporting on internal displacement caused by conflict, generalized violence, and violations of human rights; training and strengthening capacities on the protection of IDPs; and contributing to the development of standards and guidance on protecting and assisting IDPs. For further information, please visit www.internal-displacement.org Acknowledgements This report was researched and written by Laura Perez for Watchlist and IDMC. Watchlist and IDMC are very grateful to Cooperazione Internazionale (COOPI), the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) for making this study possible by facilitating interviews and group discussions with children affected by armed conflict, and by providing assistance, accommodation, transportation, and security in their respective field offices.