Karlovy Vary 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extracts of Orfeu Da Conceição (Translated by David Treece)

Extracts of Orfeu da Conceição (translated by David Treece) Extracts of Orfeu da Conceição (translated by David Treece) The poems and songs here translated are from the play Orfeu da Conceição, by Vinicius de Moraes and Antonio Carlos Jobim. This selection was part of the libretto for “Playing with Orpheus”, performed by the King’s Brazil Ensemble in October 2016, as part of the Festival of Arts and Humanities at King’s College London. Orpheus Eurydice… Eurydice… Eurydice … The name that bids one to speak Of love: name of my love, which the wind Learned so as to pluck the flower’s petals Name of the nameless star… Eurydice… Coryphaeus The perils of this life are too many For those who feel passion, above all When a moon suddenly appears And hangs there in the sky, as if forgotten. And if the moonlight in its wild frenzy Is joined by some melody Then you must watch out For a woman must be there about. A woman must be there about, made Of music, moonlight and feeling And life won’t let her be, so perfect is she. A woman who is like the very Moon: So lovely that she leaves a trail of suffering So filled with innocence that she stands naked there. Orpheus Eurydice… Eurydice… Eurydice… The name that asks to speak Of love: name of my love, which the wind - 597 - RASILIANA: Journal for Brazilian Studies. ISSN 2245-4373. Vol. 9 No. 1 (2020). Extracts of Orfeu da Conceição (translated by David Treece) Learned so as to pluck the flower’s petals Name of the nameless star… Eurydice… A Woman’s name A woman’s name Just a name, no more… And a self-respecting man Breaks down and weeps And acts against his will And is deprived of peace. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Half Title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS in CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN

<half title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS</half title> i Traditions in World Cinema General Editors Linda Badley (Middle Tennessee State University) R. Barton Palmer (Clemson University) Founding Editor Steven Jay Schneider (New York University) Titles in the series include: Traditions in World Cinema Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Jay Schneider (eds) Japanese Horror Cinema Jay McRoy (ed.) New Punk Cinema Nicholas Rombes (ed.) African Filmmaking Roy Armes Palestinian Cinema Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi Czech and Slovak Cinema Peter Hames The New Neapolitan Cinema Alex Marlow-Mann American Smart Cinema Claire Perkins The International Film Musical Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad (eds) Italian Neorealist Cinema Torunn Haaland Magic Realist Cinema in East Central Europe Aga Skrodzka Italian Post-Neorealist Cinema Luca Barattoni Spanish Horror Film Antonio Lázaro-Reboll Post-beur Cinema ii Will Higbee New Taiwanese Cinema in Focus Flannery Wilson International Noir Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer (eds) Films on Ice Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport (eds) Nordic Genre Film Tommy Gustafsson and Pietari Kääpä (eds) Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-Bi Adam Bingham Chinese Martial Arts Cinema (2nd edition) Stephen Teo Slow Cinema Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge Expressionism in Cinema Olaf Brill and Gary D. Rhodes (eds) French Language Road Cinema: Borders,Diasporas, Migration and ‘NewEurope’ Michael Gott Transnational Film Remakes Iain Robert Smith and Constantine Verevis Coming-of-age Cinema in New Zealand Alistair Fox New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas Dolores Tierney www.euppublishing.com/series/tiwc iii <title page>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS Dolores Tierney <EUP title page logo> </title page> iv <imprint page> Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. -

Performeando Orfeu Negro

Performeando Orfeu Negro Leslie O’Toole The University of Arizona a película Orfeu Negro es una coproducción entre Brasil y Francia, con un direc- tor francés. Fue estrenada en 1959 con mucha aclamación crítica fuera de Brasil. Ganó una cantidad de premios, incluyendo el Palm d’Or en 1959 en Cannes, Llos premios Golden Globe y Academy Award para en 1960 Mejor Película Extranjera y el premio BAFTA en 1961. Antes del premio BAFTA fue considerada una película francesa, pero con este premio recibió la atribución de ser una coproducción. Aunque la película era muy popular en todo el mundo, los brasileños tenían algunas frustra- ciones con la imagen extranjera de Brasil que muestra. Orfeu Negro tiene un director, empresa de producción y equipo de rodaje francés, por eso los brasileños sentían que la película representaba la vida de las favelas de Rio de Janeiro en una luz demasiadamente romántica y estilizada. En 2001, Carlos Diegues produjo y dirigió una nueva versión, llamada Orfeu, que tiene lugar en las modernas favelas de Rio de Janeiro. Esta película, que muestra la banda sonora de Caetano Veloso, un famoso músico brasileño y uno de los fundadores del estilo tropicalismo, fue bien recibida por el publico brasileño pero no recibió mucha aclamación o atención fuera de Brasil. ¿Cómo podía embelesar una película como Orfeu Negro su audiencia mundial y por qué continúa de cautivar su atención? Creo que Orfeu Negro, con la metaforicalización de un mito, ha tocado tantas personas porque muestra nuestros deseos y humanidad. Propongo investigar cómo la película cumple esta visualización a través del uso de dife- rentes teóricos, filósofos y antropólogos, más predominantemente, Mikhail Bakhtin, Victor Turner y Joseph Roach. -

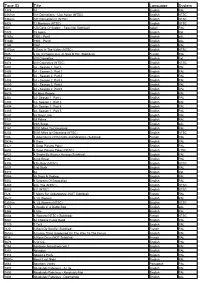

GCSE, AS and a Level Music Difficulty Levels Booklet

GCSE, AS and A level Music Difficulty Levels Booklet Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9 - 1) in Music (1MU0) Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Music (8MU0) Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced GCE in Music (9MU0) First teaching from September 2016 First certification from 2017 (AS) 2018 (GCSE and A level) Issue 1 Contents Introduction 1 Difficulty Levels 3 Piano 3 Violin 48 Cello 71 Flute 90 Oboe 125 Cla rinet 146 Saxophone 179 Trumpet 217 Voic e 240 Voic e (popula r) 301 Guitar (c lassic al) 313 Guitar (popula r) 330 Elec tronic keyboa rd 338 Drum kit 344 Bass Guitar 354 Percussion 358 Introduction This guide relates to the Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9-1) in Music (1MU0), Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Music (8MU0) and Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced GCE in Music (9MU0) qualifications for first teaching from 2016. This guide must be read and used in conjunction with the relevant specifications. The music listed in this guide is designed to help students, teachers, moderators and examiners accurately judge the difficulty level of music submitted for the Performing components of the Pearson Edexcel GCSE, AS and A level Music qualifications. Examples of solo pieces are provided for the most commonly presented instruments across the full range of levels. Using these difficult y levels For GCSE, teachers will need to use the book to determine the difficulty level(s) of piece(s) performed and apply these when marking performances. For AS and A Level, this book can be used as a guide to assist in choosing pieces to perform, as performances are externally marked. -

Orfeu: Mito, Ópera E Poesia. Um Estudo Comparado Orpheus: Myth, Opera and Poetry

Orfeu: mito, ópera e poesia. Um estudo comparado Orpheus: myth, opera and poetry. A comparative study. Maria Vitoria Fregni Adriane da Silva Duarte 1 Resumo: Este artigo tem por objetivo a análise do libreto da ópera L'Orfeo , de Claudio Monteverdi, escrito por Alessandro Striggio, baseado no mito grego de Orfeu. Com isso, busca- se estabelecer uma aproximação entre o estudo da Literatura e o da Música, o que é mais do que natural, uma vez que em sua origem essas artes eram inseparáveis. Palavra-chave: mitologia; ópera; Barroco; Monteverdi; Orfeu. Abstract: This paper intends to analyze the libretto of Claudio Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo , written by Alessandro Striggio, based on Orpheus' myth. It's natural to examine poetry and music simultaneously, since they were inseparable for a long time. Keywords: mythology, opera, baroque, Monteverdi, Orpheus. A ópera surgiu na transição do século XVI para o XVII, em um colegiado de nobres de Florença conhecido como Camerata Fiorentina. Destinada ao estudo da cultura clássica, a Camerata era composta por músicos amadores, todos membros da aristocracia italiana. Esses nobres se dedicavam ao estudo da cultura clássica, em especial do teatro grego, no qual se inspiraram para inaugurar um novo gênero: o drama musical. Abandonando a estética musical vigente até então, os florentinos buscavam a fidelidade à palavra recitada, capaz de captar o ouvinte através da expressão objetiva do potencial melódico da fala do orador. Com isso, desenvolveram uma nova maneira de escrever música para voz: o estilo Recitativo , um intermediário entre a recitação falada e a canção. Com base nessa nova música, os fiorentinos compuseram duas obras dramático-musicais, Dafne (Peri, 1597) e L’Euridice (Rinuccini e Peri, 1600), ambas com enredo baseado em passagens da mitologia clássica, como seria 1 Maria Vitoria Fregni é graduanda do curso de Música da ECA/USP. -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Required Text: Robert Stam, Tropical Multiculturalism: a Comparative History of Race in Brazilian Cinema and Culture (Duke UP, 2004)

Film 162 The Afro-Brazilian Experience and Brazilian Cinema Fall 2008: Tuesdays & Thursdays, 8:00-9:50; Horace Mann 193 Instructor: Vincent Bohlinger Office: Craig-Lee 355 Telephone: x8660 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Thursdays 10:00-11:50, also by appointment Course Overview: This course serves as an introduction to the cinema of Brazil by way of exploring issues of race and representation. We start with a study of the international stereotypes surrounding Brazil, then examine the Cinema Nôvo movement, and finally move toward commercial and critical successes of the past few decades. We will be analyzing a number of challenging films in order to understand their broader political, cultural, and aesthetic contexts. Required Text: Robert Stam, Tropical Multiculturalism: A Comparative History of Race in Brazilian Cinema and Culture (Duke UP, 2004) Recommended: one of the following dvds (for the analysis paper): Pixote (Hector Babenco, 1981); City of God (Fernando Meirelles, 2002); Madame Satã (Karim Aïnouz, 2002); Bus 174 (José Padilha, 2002); The Man Who Copied (Jorge Furtado, 2003); Antônia (Tata Amaral, 2006) Course Requirements: 10% Participation (note attendance policy below) 20% Mid-Term Exam (in class) 20% Research Paper (5-7 pages) 20% Analysis Paper (5-7 pages) 30% Final Exam (in class) Course Policies: - Attendance is mandatory and counts toward the participation grade. More than three absences will result in a lower grade and possibly course failure. - Please come to class on time and remain in class for the duration of the session. Late arrivals and early departures count as partial absences, as do temporary exits during screening, lecture, or discussion. -

M O N T E V E R

MONTEVERDI Music is the servant of the words 2012 LET US INNOVATE by Simone Kotva FROM IMITATION OF NATURE MONTEVERDI’S REVERSAL TO NATURAL IMITATION At the turn of the sixteenth century, the cusp of Monteverdi christened his musical aesthetics the We should see what are the rhythms of a self- The sentence immediately preceding Plato’s antici - what historians have since called “the modern era,” seconda prattica , or Second Practice. Its purpose disciplined and courageous life, and after looking at pation of Monteverdi’s motto is a discussion of the Claudio Monteverdi poses the perennial question was to oppose the establishment, what he called those, make meter and melody conform to the leitmotif of Classical philosophy, namely the “self- of every artist: how do my compositions relate to the First Practice of music theory. Monteverdi speech of someone like that. We won’t make disciplined and courageous life,” or human nature. those of past masters? How does innovation characterised the First Practice (whether justly or speech conform to rhythm and melody . Plato’s belief (which was also Aristotle’s) was that relate to imitation? not), as concerned exclusively with the rules of (Republic 400a; my emphasis) human nature was formed through a life-long pro - “pure” harmony stripped of any relation to text, cess of cultivating good habits. These good habits For Monteverdi, living in a time of vitriolic polemics rhythm and melody. It philosophical foundations The final sentence mirrors the emphatic declara - would eventually lead to good virtues, -

Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette

Tracing Eurydice: Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette Master’s Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Media Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2013 © Ryan Cadrette, 2013 iii Abstract Tracing Eurydice: Adaptation and Narrative Structure in the Orpheus Myth Ryan Cadrette The primary purpose of this thesis is to postulate a working method of critical inquiry into the processes of narrative adaptation by examining the consistencies and ruptures of a story as it moves across representational form. In order to accomplish this, I will draw upon the method of structuralist textual analysis employed by Roland Barthes in his essay S/Z to produce a comparative study of three versions of the Orpheus myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. By reviewing the five codes of meaning described by Barthes in S/Z through the lens of contemporary adaptation theory, I hope to discern a structural basis for the persistence of adapted narrative. By applying these theories to texts in a variety of different media, I will also assess the limitations of Barthes’ methodology, evaluating its utility as a critical tool for post-literary narrative forms. iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Peter van Wyck, for his reassurance that earlier drafts of this thesis were not necessarily indicative of insanity, and, hopefully, for his forgiveness of my failure to incorporate all of his particularly insightful feedback. I would also like to thank Matt Soar and Darren Wershler for agreeing to actually read the peculiar monstrosity I have assembled here. -

Black Orpheus, Myth and Ritual: a Morphological Reading*

DOI 10.1007/s12138-008-0009-y Black Orpheus, Myth and Ritual: A Morphological Reading* HARDY FREDRICKSMEYER # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2008 Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro; M. Camus, 1959) drew on classical myth and ritual to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Yet no one has analyzed the film with reference to its classical background. This paper argues that the film closely follows two narrative patterns (Separation-Liminality- Incorporation and the Heroic Journey) employed by the myth of Orpheus and Eury- dice, and related stories. This morphological approach reveals the cinematic Euridice as a “female adolescent initiand” whose loss of virginity and death are foreshadowed from her first scene. The film’s setting of Carnaval promotes Euridice’s adolescent ini- tiation as it duplicates ancient Greek Dionysian festivals. Orfeu emerges as not only a shamanistic hero, but also an associate of Apollo and, antithetically, an avatar of Diony- sus and substitute sacrifice for the god. Finally, the film not only replicates but also reinvents the ancient, rural and European myth of Orpheus and Eurydice by resituat- ing it in a modern city of the Africanized “New World.” A Stephanie, la compagna della mia vita lack Orpheus (Orfeu Negro; M. Camus, 1959) explodes on the screen as a Bsensual tour de force of color, music and dance, all framed by the rhapsodic beauty of Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval. Critical and popular admiration for these audio-visual qualities help to explain why Black Orpheus won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and why it remains one of the most successful films of all time with a Latin-Amer- * For their thoughtful comments on earlier versions of this essay, I would like to thank the editor of this journal, Wolfgang Haase, the anonymous referees, Erwin Cook, John Gibert, Ernst Fredricksmeyer, and Donald Wilkerson. -

Carlos Diegues

CARLOS DIEGUES Carlos Diegues was born in Maceió, Alagoas, in May 19th, 1940. He is one of the most famous filmmaker of all Brazilian history. Early in the 1960s, Diegues co-founded the Cinema Novo movement with Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Paulo Cezar Saraceni and others. In the 1970s, he started a time of great popularity of the Brazilian cinema with his film “Xica da Silva”, still one of the most worshiped and adored films of his cinematography. In the beginning of the 1980s, he filmed “Bye Bye Brasil”, one of the most famous Brazilian films worldwide. Diegues’ filmography, known by his fellow countrymen as Caca, a kind short name for Carlos, becomes popular and artistic, reflexive and charming at the same time. A militant artist and an intellectual combatant, Diegues opposed to the military dictatorship in his country, that lasted from the 1960s to early 1980s. During that period, he had to leave for exile. Diegues’ public interventions in politics, culture and cinema, through books, articles and interviews, still causes controversial viewpoints. The majority of his films were released commercially in almost all of the countries in the world, having also taken part in the official selection of important film festivals around the world, such as Cannes (where he was also member of the official jury, in 1981, jury of Cine Fundation in 2010 and president of Camera D’Or in 2013), Venice, Berlin, Toronto, Locarno, Montreal, San Sebastian, New York, and many others, making Carlos Diegues one of Latin America’s most well known and respected movie directors in the world.