ADGRG1 in Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Neuregulin 1–Erbb2 Signaling Is Required for the Establishment of Radial Glia and Their Transformation Into Astrocytes in Cerebral Cortex

Neuregulin 1–erbB2 signaling is required for the establishment of radial glia and their transformation into astrocytes in cerebral cortex Ralf S. Schmid*, Barbara McGrath*, Bridget E. Berechid†, Becky Boyles*, Mark Marchionni‡, Nenad Sˇ estan†, and Eva S. Anton*§ *University of North Carolina Neuroscience Center and Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; †Department of Neurobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510; and ‡CeNes Pharamceuticals, Inc., Norwood, MA 02062 Communicated by Pasko Rakic, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, January 27, 2003 (received for review December 12, 2002) Radial glial cells and astrocytes function to support the construction mine whether NRG-1-mediated signaling is involved in radial and maintenance, respectively, of the cerebral cortex. However, the glial cell development and differentiation in the cerebral cortex. mechanisms that determine how radial glial cells are established, We show that NRG-1 signaling, involving erbB2, may act in maintained, and transformed into astrocytes in the cerebral cortex are concert with Notch signaling to exert a critical influence in the not well understood. Here, we show that neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) exerts establishment, maintenance, and appropriate transformation of a critical role in the establishment of radial glial cells. Radial glial cell radial glial cells in cerebral cortex. generation is significantly impaired in NRG mutants, and this defect can be rescued by exogenous NRG-1. Down-regulation of expression Materials and Methods and activity of erbB2, a member of the NRG-1 receptor complex, leads Clonal Analysis to Study NRG’s Role in the Initial Establishment of to the transformation of radial glial cells into astrocytes. -

Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS

The Journal of Neuroscience, April 1992, 12(4): 1538-l 547 Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS Regina C. Armstrong,lJ Henry H. Dorn, l,b Conrad V. Kufta,* Emily Friedman,3 and Monique E. Dubois-Dalcq’ ‘Laboratory of Viral and Molecular Pathogenesis, and %urgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 and 3Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-3246 CNS remyelination and functional recovery often occur after Rapid and efficient neurotransmission is dependent upon the experimental demyelination in adult rodents. This has been electrical insulating capacity of the myelin sheath around axons attributed to the ability of mature oligodendrocytes and/or (reviewed in Ritchie, 1984a,b). Nerve conduction is impaired their precursor cells to divide and regenerate in response after loss of the myelin sheath and results in severe neurological to signals in demyelinating lesions. To determine whether dysfunction in human demyelinating diseases such as multiple oligodendrocyte precursor cells exist in the adult human sclerosis (MS). Remyelination can occur in the CNS of MS CNS, we have cultured white matter from patients under- patients but appears to be limited (Perier and Gregoire, 1965; going partial temporal lobe resection for intractable epilep- Prineas et al., 1984). Studies of acute MS cases have revealed sy. These cultures contained a population of process-bear- that recent demyelinating lesions can exhibit remyelination that ing cells that expressed antigens recognized by the 04 appears to correlate with the generation of new oligodendrocytes monoclonal antibody, but these cells did not express galac- (Prineas et al., 1984; Raine et al., 1988). -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

View Software

TLR4-activated microglia have divergent effects on oligodendrocyte lineage cells DISSERTATION Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Evan Zachary Goldstein, BA Neuroscience Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Dana McTigue, Advisor Dr. Phillip Popovich Dr. Jonathan Godbout Dr. Courtney DeVries Copyright by Evan Zachary Goldstein 2016 i Abstract Myelin accelerates action potential conduction velocity and provides essential metabolic support for axons. Unfortunately, myelin and myelinating cells are often vulnerable to injury or disease, resulting in myelin damage, which in turn can lead to axon dysfunction, overt pathology and neurological impairment. Inflammation is a common component of CNS trauma and disease, and therefore an active inflammatory response is often considered deleterious to myelin health. While inflammation can certainly damage myelin, inflammatory processes also benefit oligodendrocyte (OL) lineage progression and myelin repair. Consistent with the divergent nature of inflammation, intraspinal toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation, an innate immune pathway, kills OL lineage cells, but also initiates oligodendrogenesis. Soluble factors produced by TLR4-activated microglia can reproduce these effects in vitro, however the exact factors are unknown. To determine what microglial factors might contribute to TLR4-induced OL loss and oligodendrogenesis, mRNA of factors known to affect OL lineage cells was quantified in TLR4-activated microglia and spinal cords (chapter 2). Results indicate that TLR4-activated microglia transcribe numerous factors that induce OL loss, OL progenitor cell (OPC) proliferation and OPC differentiation. However, some factors upregulated after intraspinal TLR4 activation were not ii upregulated by microglia, suggesting that other cell types contribute to transcriptional changes in vivo. -

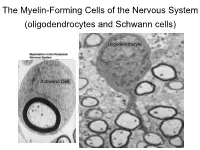

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Specific Labeling of Synaptic Schwann Cells Reveals Unique Cellular And

RESEARCH ARTICLE Specific labeling of synaptic schwann cells reveals unique cellular and molecular features Ryan Castro1,2,3, Thomas Taetzsch1,2, Sydney K Vaughan1,2, Kerilyn Godbe4, John Chappell4, Robert E Settlage5, Gregorio Valdez1,2,6* 1Department of Molecular Biology, Cellular Biology, and Biochemistry, Brown University, Providence, United States; 2Center for Translational Neuroscience, Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science and Brown Institute for Translational Science, Brown University, Providence, United States; 3Neuroscience Graduate Program, Brown University, Providence, United States; 4Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech Carilion, Roanoke, United States; 5Department of Advanced Research Computing, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, United States; 6Department of Neurology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, United States Abstract Perisynaptic Schwann cells (PSCs) are specialized, non-myelinating, synaptic glia of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), that participate in synapse development, function, maintenance, and repair. The study of PSCs has relied on an anatomy-based approach, as the identities of cell-specific PSC molecular markers have remained elusive. This limited approach has precluded our ability to isolate and genetically manipulate PSCs in a cell specific manner. We have identified neuron-glia antigen 2 (NG2) as a unique molecular marker of S100b+ PSCs in skeletal muscle. NG2 is expressed in Schwann cells already associated with the NMJ, indicating that it is a marker of differentiated PSCs. Using a newly generated transgenic mouse in which PSCs are specifically labeled, we show that PSCs have a unique molecular signature that includes genes known to play critical roles in *For correspondence: PSCs and synapses. These findings will serve as a springboard for revealing drivers of PSC [email protected] differentiation and function. -

ARIA Is Concentrated in Nerve Terminals at Neuromuscular Junctions and at Other Synapses

The Journal of Neuroscience, September 1995, 15(g): 6124-6136 ARIA Is Concentrated in Nerve Terminals at Neuromuscular Junctions and at Other Synapses Alfred W. Sandrock, Jr.,i,2 Andrew D. J. Goodearl,’ Qin-Wei Yin,’ David Chang,3 and Gerald D. Fischbachl ‘Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, “Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hosoital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, and 3Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, California 91320 Skeletal muscle ACh receptors (AChRs) accumulate at neu- natal maturation of AChRs at the neuromuscular junction, which romuscular junctions (nmjs) at least partly because of the results in the replacement of y-subunit-containing receptors with selective induction of AChR subunit genes in subsynaptic those containing E- subunits (Brenner and Sakmann, 1978; Bren- myotube nuclei by the motor nerve terminal. Additionally, ner et al., 1990; Martinou and Merlie, 1991). ARIA (for ACh mammalian AChRs undergo a postnatal change in subunit receptor inducing activity), which was purified from chicken composition from embryonic (cw.&S) to adult (@eS) brains based on its ability to stimulate the synthesis of AChRs forms, a switch that also depends on innervation. ARIA, a in skeletal muscle (Falls et al., 1993), may mediate the ability protein purified from chicken brains based on its ability to of the motor neuron to orchestrate these developmental events. induce AChR synthesis in primary chick muscle cells, is a ARIA mRNA is concentrated in chick and rat motor neurons strong candidate for being the molecule responsible for (Falls et al., 1993; Corfas et al., 1995), and, in both species, is these early developmental events. -

Plasticity in the Adult Human Oligodendrocyte Lineage

The Journal of Neuroscience, August 1994, 74(8): 4571-4587 Plasticity in the Adult Human Oligodendrocyte Lineage Nitin Gogate, ‘.a Lalit Verma,l,b Jia Min Zhou,’ Elizabeth Milward,’ Ray Rusten,’ Michael O’Connor,3 Conrad Kufta,* Jin Kim,’ Lynn Hudson,’ and Monique Dubois-Dalcql ‘Laboratory of Viral and Molecular Pathogenesis and *Neurosurgery Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 and 3The Graduate Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Preoligodendrocytes have been described in cultures and [Key words: human brain, oligodendrocytes, regeneration, tissue prints of adult human white matter (Armstrong et al., myelin genes, developmentally regulated genes PDGFaR and 1992). To characterize further these precursors of human MyTl, basic fibroblast growth factor, in situ hybridization] oligodendrocytes, we have investigated whether they ex- press genes playing a critical role in oligodendrocyte de- In the mammalian CNS, oligodendrocytessynthesize the myelin velopment. In the intact human brain, platelet-derived growth sheathsthat enwrap most CNS axons and allow rapid and ef- factor receptor a (PDGFaR) and myelin transcription factor ficient conduction of impulsesalong the nerve tracts (Ritchie, 1 (MyTI) transcripts are expressed in l-2% of cells of the 1984). In demyelinating diseasescaused by viral infection or oligodendrocyte lineage (OL), and clusters of such cells can autoimmune reaction, multifocal lossof myelin results in neu- be found in the periventricular region. Myelin basic protein rological dysfunction of varying severity (Alvord et al., 1992; transcripts containing exon 2 information (exon 2+ MBP), Fazakerley and Buchmeier, 1992). However, oligodendrocytes which are characteristic of the premyelinating stage, are can regenerate, form new myelin sheathsaround the denuded detected in 15-20% of OL cells in vitro. -

Evidence for Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cell Heterogeneity in the Adult Mouse Brain

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.06.981373; this version posted March 8, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Evidence for oligodendrocyte progenitor cell heterogeneity in the adult mouse brain. Authors: Rebecca M. Beiter1,2, Anthony Fernández-Castañeda1,2, Courtney Rivet-Noor1,2, Andrea Merchak1,2, Robin Bai1, Erica Slogar1, Scott M. Seki1,2,3, Dorian A Rosen1,4, Christopher C. Overall1,5, and Alban Gaultier1,5,# 1Center for Brain Immunology and Glia, Department of Neuroscience, 2Graduate Program in Neuroscience, 3Medical Scientist Training Program, 4Graduate Program in Pharmacological Sciences School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA. #Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 5Christopher C. Overall and Alban Gaultier are co-senior authors 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.06.981373; this version posted March 8, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. ABSTRACT Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) are a mitotically active population of glia that comprise approximately 5% of the adult brain. OPCs maintain their proliferative capacity and ability to differentiate in oligodendrocytes throughout adulthood, but relatively few mature oligodendrocytes are produced following developmental myelination. Recent work has begun to demonstrate that OPCs likely perform multiple functions in both homeostasis and disease, and can significantly impact behavioral phenotypes such as food intake and depressive symptoms. However, the exact mechanisms through which OPCs might influence brain function remains unclear. -

Regulation of Motor Axon Innervation at the Neuromuscular Junction By

Regulation of Motor Axon Innervation at the Neuromuscular Junction by Jennifer L. Shadrach A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Cellular and Molecular Biology) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Brian A. Pierchala, Chair Associate Professor Anthony Antonellis Professor Susan V. Brooks Professor Roman J. Giger Professor Daniel Goldman Jennifer L. Shadrach [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5266-8625 © Jennifer L. Shadrach 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: First, I would like to thank Dr. Brian Pierchala for the opportunity to work in your laboratory. I have benefited greatly from your guidance and support over the past five years. Additionally, I appreciate your willingness in allowing me to explore my scientific interests and develop into an independent researcher. What I have learned from my experiences will be extremely valuable as I pursue my future scientific career. I would also like to thank the entire Pierchala lab for their help and insights over the years. In particular, I would like thank Allison Milan for her technical assistance throughout this past year. Finally, a special thanks to Chris Donnelly – without both your scientific input and friendship over the years my graduate school experience would have not been the same. To my committee members, thank you for your time, wisdom, and guidance throughout my graduate training. Your thoughtful comments and advice, as well as your willingness to share various protocols and reagents have been greatly appreciated. Finally, I would like to thank the Cellular and Molecular Biology Program and all my friends and colleagues for supporting me throughout graduate school career. -

BMP and LIF Signaling Coordinately Regulate Lineage Restriction of Radial Glia in the Developing Forebrain

BMP and LIF Signaling Coordinately Regulate Lineage Restriction of Radial Glia in the Developing Forebrain HEDONG LI AND MARTIN GRUMET* Department of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, w: M. Keck Center for Collaborative Neuroscience, Rutgers, State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, New Jersey KEYWORDS Early expression of certain secreted factors in neural cortical development; restricted precursors; A2B5; 5A5; 4D4; development suggests that they play critical roles in GRP;NRP neural lineage restriction and cell differentiation. Neural stem cells appear early during development as neuro- epithelial cells expressing nestin and vimentin and sub- ABSTRACT sequent expression of additional markers such as BLBP The earliest radial glia are neural stem cells that guide neural cell migration away from ventricular zones. Subsequently, ra- and GLAST defines radial glial cells (Anthony et al., dial glia become lineage restricted during development before 2004; Conti et al., 2005; Noctor et al., 2002). The term ra- they differentiate into more mature cell types in the CNS. We dial glia has generated significant confusion in part have previously shown that subpopulations of radial glial cells because it has been debated whether they are glia (Gotz express markers for glial and neuronal restricted precursors and Barde, 2005; Morest and Silver, 2003) or should be (GRPs and NRPs) in expression patterns that are temporally called radial precursors (Ever and Gaiano, 2005). How- and spatially regulated during CNS development. To charac- ever, embryonic radial glia have been defined by a combi- terize further the mechanism of this regulation in rat fore- nation of their morphology and distinguishing character- brain, we tested whether secreted factors that are present dur- istics (e.g.