Program and Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Wildlife Service Permit Application

For office use only Date Received Permit No. CANADIAN WILDLIFE SERVICE PERMIT APPLICATION NOTE TO RESEARCHERS Without exception, all research within the NWT and Nunavut must be licensed. This includes work in indigenous knowledge as well as in physical, social, and biological sciences. For information on licensing for your project within the NWT, please refer to the Aurora Research Institute’s Web site at http://www.nwtresearch.com. For Nunavut, visit the Nunavut Research Institute Web site at http://www.nri.nu.ca. For Scientific Permits: Prior to issuing a Scientific Permit to Take, Salvage or Disturb Migratory Birds, CWS requires: 1) Copy of either an NWT or Nunavut Wildlife Research Permit; or an Aurora Research Licence/Nunavut Research Licence. Include a copy of either the permit or the licence with this application or forward a copy to CWS upon receipt of it. Otherwise, your permit will not be issued. 2) Appendix 1 of this permit application must be completed by two ornithologists who have reviewed the application and are willing to attest to the ability and professionalism of the applicant. Nunavut: In Nunavut your project will have to undergo screening by the Nunavut Impact Review Board. One of their requirements is that you obtain a conformity report from the Nunavut Planning Commission. Please ensure that you have done so. To be completed by all applicants: New application Type of permit applied for: Amendment/extension of existing permit Bird Sanctuary permit Existing permit no. National Wildlife Area entry permit Scientific -

Gene and Transposable Element Expression

Gene and Transposable Element Expression Evolution Following Recent and Past Polyploidy Events in Spartina (Poaceae) Delphine Giraud, Oscar Lima, Mathieu Rousseau-Gueutin, Armel Salmon, Malika Ainouche To cite this version: Delphine Giraud, Oscar Lima, Mathieu Rousseau-Gueutin, Armel Salmon, Malika Ainouche. Gene and Transposable Element Expression Evolution Following Recent and Past Polyploidy Events in Spartina (Poaceae). Frontiers in Genetics, 2021, 12, 10.3389/fgene.2021.589160. hal-03216905 HAL Id: hal-03216905 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03216905 Submitted on 4 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License fgene-12-589160 March 19, 2021 Time: 12:36 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 25 March 2021 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.589160 Gene and Transposable Element Expression Evolution Following Recent and Past Polyploidy Events in Spartina (Poaceae) Delphine Giraud1, Oscar Lima1, Mathieu Rousseau-Gueutin2, Armel Salmon1 and Malika Aïnouche1* 1 UMR CNRS 6553 Ecosystèmes, Biodiversité, Evolution (ECOBIO), Université de Rennes 1, Rennes, France, 2 IGEPP, INRAE, Institut Agro, Univ Rennes, Le Rheu, France Gene expression dynamics is a key component of polyploid evolution, varying in nature, intensity, and temporal scales, most particularly in allopolyploids, where two or more sub-genomes from differentiated parental species and different repeat contents are merged. -

Wetland Birds in the Recent Fossil Record of Britain and Northwest Europe John R

Wetland birds in the recent fossil record of Britain and northwest Europe John R. Stewart 18. Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus, Deep Bay, Mai Po, Hong Kong, February 1995. Geological evidence suggests that Dalmatian Pelicans bred in Britain, and in other western European countries (including The Netherlands and Denmark), prior to and during the Iron Age. Ray Tipper. ABSTRACT Wetland habitats in Britain and other parts of western Europe have been severely depleted during the latter part of the Holocene owing principally to drainage and land reclamation. Changes in the distribution of a number of wetland bird species can be gauged from archaeological and geological site records of larger birds, whose remains are generally better preserved. Key species are discussed here, including a heron Nycticorax fenensis and a crane Grus primigenia, two extinct species named on possibly uncertain fossil evidence. We can let our minds wander back to the misty realms of fifteen hundred years ago, to a wonderful Britain which was alive with bird song from coast to coast, which sheltered wolves, bears and boars in its dark woodlands, cranes in its marshes, bustards on its heaths and beavers by its streams, and we can visualize the great pink pelican sweeping on its huge pinions over the reedy waterways which then penetrated by secret paths into the very heart of what is now Somerset. (Whitlock, 1953) © British Birds 97 • January 2004 • 33-43 33 Wetland birds in the recent fossil record f all the major habitats in northwest species, including Mute Swan Cygnus olor and Europe, wetlands may have been the Common Crane, may have become physically Omost severely depleted during the smaller owing to habitat impoverishment. -

Dalmatian Pelican Identification Manual Companion Document to the “Dalmatian Pelican Monitoring Manual”

Pelican Way of LIFE (LIFE18 NAT/NL/716) “Conservation of the Dalmatian Pelican along the Black Sea - Mediterranean Flyway” Dalmatian Pelican Identification Manual Companion document to the “Dalmatian Pelican Monitoring Manual” December 2020 Authored by: Commissioned by: Giorgos Catsadorakis and Olga Alexandrou, Society for the Protection of Prespa Rewilding Europe Dalmatian Pelican Identification Manual - Companion document to the “Dalmatian Pelican Monitoring Manual” December 2020 Authors: Giorgos Catsadorakis1 and Olga Alexandrou2 1,2Society for the Protection of Prespa, Agios Germanos, GR-53150, Prespa, Greece, [email protected] , [email protected] © Rewilding Europe Executed under the framework of “Conservation of the Dalmatian Pelican along the Black Sea - Mediterranean Flyway” (Pelican Way of LIFE; LIFE18 NAT/NL/716; https://life-pelicans.com/) project, financed by the LIFE programme of the European Union and Arcadia – a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. Suggested citation: Society for the Protection of Prespa, 2020. Dalmatian pelican identification manual - Companion document to the “Dalmatian pelican monitoring manual”. Rewilding Europe. Produced within the framework of Pelican Way of LIFE project (LIFE18 NAT/NL/716). Keywords: Dalmatian pelican, identification, ageing, plumage, moulting patterns, sexing. Photo credits: Society for the Protection of Prespa, unless stated otherwise. Introduction Visual identification of the Dalmatian pelican seems like a straightforward task, yet in sites used by both species (the Dalmatian pelican and the great white pelican) identification can be tricky, especially when the observer is located some distance away from the birds. Hardly any useful material has been published on the sequence of moults and plumages of the Dalmatian pelican, and this gap often creates confusion and uncertainty about the accuracy of data in regards to ageing of Dalmatian pelicans, as well as frequently undermining confidence in census numbers. -

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

Pelecanus Occidentalis) in Costa Rica

First record of leucism in brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) in Costa Rica Primer registro de leucismo en el pelícano pardo (Pelecanus occidentalis) en Costa Rica Roberto Vargas-Masís*1,2 & Pilar Arguedas-Rodríguez1,3 ABSTRACT Leucism in birds is rarely observed in the Pelecaniformes order and has not been recorded for the brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) in Costa Rica. We describe an observation of a leucistic brown pelican with white plumage, pink coloration on the bill and feet, but normal color on the eyes. Leucism in birds is the most frequently reported color aberration and these cases present low survival rates for individuals. Although isolated cases occur in birds, these reports help determine the frequency of these events for spe- cific bird populations and species. Keywords: Leucism, brown pelican, plumage, albinism, Costa Rica. RESUMEN El leucismo en las aves se observa raramente en el orden Pelecaniformes y no ha sido registrado para el pe- lícano pardo (Pelecanus occidentalis) en Costa Rica. Describimos una observación de un pelícano marrón leucístico con plumaje blanco, coloración rosa en el pico y las patas, pero color normal en los ojos. El leu- cismo en las aves es la aberración de color más frecuentemente reportada y estos casos presentan tasas bajas de supervivencia para los individuos. Aunque se presentan casos aislados en aves, estos reportes permiten determinar la frecuencia de estos eventos en ciertas poblaciones y especies de aves. Palabras claves: Leucismo, pelícano pardo, plumaje, albinismo, Costa Rica. INTRODUCTION Birds obtain their coloration from pigments or refractive structures in feathers and skin (Yusti-Muñoz & Velandia-Perilla, 2013). -

A Record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion Fuscatus from Gujarat, India M

22 Indian BIRDS VOL. 10 NO. 1 (PUBL. 30 APRIL 2015) A record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus from Gujarat, India M. U. Jat & B. M. Parasharya Jat, M.U., & Parasharya, B. M., 2015. A record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus in Gujarat, India. Indian BIRDS 10 (1): 22-23. M. U. Jat, 3, Anand Colony, Poultry Farm Road, First Gate, Atul, Valsad, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] [MUJ] B. M. Parasharya, AINP on Agricultural Ornithology, Anand Agricultural University, Anand 388110, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] [BMP] Manuscript received on 18 March 2014. he Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus is a seabird of been rescued by Punit Patel at Khadki Village, near Pardi Town the tropical oceans that breeds on islands throughout (20.517°N, 72.933°E), Valsad District, in Gujarat. Khadki is seven Tthe equatorial zone. Within limits of the Indian kilometers east of the coast. The tern was feeble and unable Subcontinent, its race O. f. nubilosa is known to breed in to fly, though it would spread its wings when disturbed [18]. Lakshadweep on the Cherbaniani Reef, and the Pitti Islands, the The bird was photographed and its plumage described. It was Vengurla Rocks off the western coast of the Indian Peninsula, weighed and sexed the next day, when it died. Its morphometric north-western Sri Lanka, and, reportedly, in the Maldives (Ali & measurements (after Dhindsa & Sandhu 1984; Reynolds et al. Ripley 1981; Pande et al. 2007; Rasmussen & Anderton 2012). 2008) were taken using ruled scale, divider, and digital vernier Storm blown vagrants have occurred far inland (Ali & Ripley calipers to the nearest 0.1 mm. -

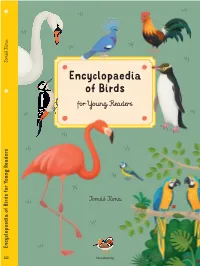

Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, Member of Albatros Media Group, 2020

✹ Tomáš Tůma Tomáš ✹ ✹ We all know that there are many birds in the sky, but did you know that there is a similar Encyclopaedia vast number on our planet’s surface? The bird kingdom is weird, wonderful, vivid ✹ of Birds and fascinating. This encyclopaedia will introduce you to over a hundred of the for Young Readers world’s best-known birds, as well as giving you a clear idea of the orders in which birds ✹ ✹ are classified. You will find an attractive selection of birds of prey, parrots, penguins, songbirds and aquatic birds from practically every corner of Planet Earth. The magnificent full-colour illustrations and easy-to-read text make this book a handy guide that every pre- schooler and young schoolchild will enjoy. Tomáš Tůma www.b4upublishing.com Readers Young Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, member of Albatros Media Group, 2020. ean + isbn Two pairs of toes, one turned forward, ✹ Toco toucan ✹ Chestnut-eared aracari ✹ Emerald toucanet the other back, are a clear indication that Piciformes spend most of their time in the trees. The beaks of toucans and aracaris The diet of the chestnut-eared The emerald toucanet lives in grow to a remarkable size. Yet aracari consists mainly of the fruit of the mountain forests of South We climb Woodpeckers hold themselves against tree-trunks these beaks are so light, they are no tropical trees. It is found in the forest America, making its nest in the using their firm tail feathers. Also characteristic impediment to the birds’ deft flight lowlands of Amazonia and in the hollow of a tree. -

Birding the Humboldt Current

BIRDING THE HUMBOLDT CURRENT We will visit the guano bird colonies of the San Lorenzo, Palomino and Cavinzas Islands, observe pelagic birds that only live offshore, we will see the huge colony of sea lions of the Palomino Islands and observe different species of cetaceans. South American Sea Lion colony | © Jean Paul Perret ITINERARY 05:40 AM Encounter at the dock and registration of the participants. 06:00 AM Boarding from the Marina Yacht Club del Callao ( location map ), located half a block from Plaza Grau in Callao, not to be confused with the La Punta club. 06:30 AM Visit to the colonies of guano birds of San Lorenzo Island. 08:00 AM Start of the “chum " bait session 16 miles from the coast. 10: 00 AM Start of return to port. 11: 00 PM Arrival at the Marina Yacht Club Del Callao. TOUR DESCRIPTION The tour begins with a short navigation to Cabezo Norte sector of San Lorenzo Island, the largest island of the Peruvian coast; at its summit we will see the Gran Almirante Grau Lighthouse. Later we will begin to observe some very interesting species of birds such as the Humboldt Penguin, the Red-legged Cormorant, Peruvian Booby, Peruvian Pelican, Guanay Cormorant, Inca Tern, Blackish Oystercatcher and the endemic Surf Cinclodes. According to the season we can also find some migratory species such as the Surfbirds, Ruddy Turnstone, Whimbrel, Royal Tern, and Elegant Tern. Humboldt Penguins | © Jean Paul Perret From this point we will go into the sea in a journey of one hour. During the navigation we will start to observe some pelagic birds such as the Peruvian Diving-petrel, Sooty Shearwaters, Pink-footed Shearwater, Wilson's Storm-petrel, Swallow-tailed Gull, Sabine's Gull, Chilean Skua, Parasite Jaeger, Phalarops and with a bit of luck Waved Albatross. -

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus Adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2020 Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes Emily Rebecca Mausteller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Mausteller, Emily Rebecca, "Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes" (2020). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1313. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1313 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EASTERN DIAMONDBACK RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS ADAMANTEUS) AMBUSH SITE SELECTION IN COASTAL SALTWATER MARSHES A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Biological Sciences by Emily Rebecca Mausteller Approved by Dr. Shane Welch, Committee Chairperson Dr. Jayme Waldron Dr. Anne Axel Marshall University December 2020 i APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Emily Mausteller, affirm that the thesis, Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the Biological Sciences Program and the College of Science. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

![A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2754/a-report-on-the-guano-producing-birds-of-peru-informe-sobre-aves-guaneras-982754.webp)

A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 197 A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru [“Informe sobre Aves Guaneras”] July 2018* *Original manuscript completed1942 William Vogt1 with translation and notes by David Cameron Duffy2 1 Deceased Associate Director of the Division of Science and Education of the Office of the Coordinator in Inter-American Affairs. 2 Director, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Organization Contact Information: Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa 3190 Maile Way, St. John 408, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA Recommended Citation: Vogt, W. with translation and notes by D.C. Duffy. 2018. A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report 197. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany. Honolulu, HI. 198 pages. Key words: El Niño, Peruvian Anchoveta (Engraulis ringens), Guanay Cormorant (Phalacrocorax bougainvillii), Peruvian Booby (Sula variegate), Peruvian Pelican (Pelecanus thagus), upwelling, bird ecology behavior nesting and breeding Place key words: Peru Translated from the surviving Spanish text: Vogt, W. 1942. Informe elevado a la Compañia Administradora del Guano par el ornitólogo americano, Señor William Vogt, a la terminación del contracto de tres años que con autorización del Supremo Gobierno celebrara con la Compañia, con el fin de que llevara a cabo estudios relativos a la mejor forma de protección de las aves guaneras y aumento de la produción de las aves guaneras.