Comparing Chinese and American Media Systems Journalism, Technology, and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People's Republic of China Briefing on EU Concerns Regarding Human Rights in China Prepared for EU-China Summit 5 September 2005

People's Republic of China Briefing on EU concerns regarding human rights in China Prepared for EU-China Summit 5 September 2005 In May of this year, representatives of the European Union decided to delay a move to lift the arms embargo against China, citing human rights concerns. They referred specifically to four areas of concern that would affect future consideration in lifting the embargo: the need for Chinese authorities to release citizens imprisoned in connection with the suppression of the 1989 pro-democracy movement; the need for reform of China’s “Re-education through Labour” (RTL) system; the need for the PRC to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); and the need to ease media censorship. Amnesty International welcomes the fact that the EU has made the lifting of its embargo contingent on human rights reform and has detailed specific areas for improvement. In this briefing Amnesty International presents an update on developments in these four areas in the lead-up to the EU-China Summit in September, 2005. Amnesty International urges the EU to take these factors and other human rights concerns into consideration in its ongoing analysis of the human rights situation in China. Release of those imprisoned in connection with 1989 pro-democracy protests A core issue raised by EU representatives as an area of human rights concern is the continued detention of individuals imprisoned for their connection to the 1989 pro-democracy movement. The EU arms embargo was imposed on 27 June 1989 as a direct response to the armed suppression by the Chinese military of the peaceful protests calling for democracy and political reforms in and around Tiananmen Square in Beijing on 3-4 June. -

Ching Cheongwas Ondecember22, Born Photo:AFP/Gettyimages Ching Cheong

CRF-2005-03-text.qxd 9/8/05 3:19 PM Page 133 Prisoner Profile: of an interview with the late purged leader husband’s innocence and reiterated his Ching Cheong Zhao Ziyang, which Ching was going to have unquestioned patriotism toward China. She published. The following day, Ching noted in particular that her husband had instructed his wife, Mary Lau, to bring his brokered meetings between researchers NO. 3,NO. 2005 COMPILED BY ZENOBIA LAI personal computer to Shenzhen. The com- from the Chinese Academy of Social Sci- puter apparently contained notes that ence (CASS) and various Hong Kong politi- Ching had kept on important policy discus- cal figures, including individuals branded as sions. dissidents, to give the central government During the first week of his detention, access to the uncensored views of critics Ching reportedly maintained regular con- of the current administration. In her letter, tact with his wife and told her not to dis- Lau urged Hu to recognize the whole- close his situation. Ching’s employer, The hearted sincerity of her husband and CASS Straits Times, soon learned of his deten- Scholar Lu Jianhua in protecting the welfare tion, but was similarly requested to keep of China, and pleaded for them to be CHINA RIGHTS FORUM the matter confidential. On May 29, Ching spared imprisonment. called his wife and urged her to visit his Although Ching Cheong is a Hong Kong Ching Cheong. Photo: AFP/Getty Images parents more often, as he did not expect to permanent resident, the Hong Kong govern- 133 return to Hong Kong any time soon. -

Three Views of Local Consciousness in Hong Kong 香港 地元 の意識、三つの視点

Volume 12 | Issue 44 | Number 1 | Article ID 4207 | Nov 02, 2014 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Three Views of Local Consciousness in Hong Kong 香港 地元 の意識、三つの視点 Ho-fung Hung Korean translation available In the meantime, the British flag or Hong Kong flag containing the Union Jack started to Chan, Koon-chung. 2012. Zhongguo tianchao appear and spread in annual July st1 and zhuyi yu Xianggang (China’s Heavenly Doctrine January 1st demonstrations in 2012. Slogans and Hong Kong). Hong Kong: Oxford University attacking mainland tourists and even “Chinese Press. colonialists” surfaced. Chin Wan. 2011. Xianggang Chengbang lun (On Hong Kong as a city state). Hong Kong: Enrich Publishing. Jiang Shigong. 2008.Zhongguo Xianggang: wenhua yu zhengzhi de shiye(China’s Hong Kong: cultural and political perspectives). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. Hong Kong has been in turmoil. The 2003 demonstration in which more than half a million demonstrators successfully forestalled the Article 23 anti-subversion legislation2, as well as the 2012 rally of 130,000 and the threat Beijing and many pro-establishment observers of general student strikes that forced the sensed the emergence of a strong localist government to shelve implementation of a identity and even a pro-independence Beijing-ordered National Education curriculum disposition. Besides explicit political in Hong Kong schools, showed that Beijing declarations that defy Beijing rule, localist and could not crack down on Hong Kong’santi-Chinese youth also initiated militant direct dissenting voices as readily as it repeatedly has action. One example was the protest that in mainland China. Such resistance victories sought to disrupt smuggling activities by have not brought a willingness to compromise mainland tourists to defend local supply of daily on fundamentals by either Hong Kong’snecessities, most of all baby formula, echoing opposition forces or Beijing. -

7 Civil Liberties: 6 Status: Not Free

China Population: 1,311,400,000 Capital: Beijing Political Rights: 7 Civil Liberties: 6 Status: Not Free Overview: In response to China’s pressing socioeconomic problems, the leadership team of President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao in 2006 continued to promote policies aimed at building a “harmonious society,” balancing economic growth with the provision of public goods such as social welfare and environmental protection. However, concerns over social stability also led to a strengthening of restrictions on the country’s media and the detention of human rights activists, civil rights lawyers, and others the authorities viewed as posing a challenge to the regime. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took power in mainland China in 1949 after defeating the nationalist Kuomintang forces in the Chinese Civil War. Aiming to strengthen his own position and hasten China’s socialist transformation, Communist leader Mao Zedong oversaw devastating mass- mobilization campaigns, such as the Great Leap Forward (1958–61) and the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), which resulted in millions of deaths and politicized nearly every aspect of daily life. Following Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping emerged as China’s paramount leader. Over the next two decades, Deng maintained the CCP’s absolute rule in the political sphere while guiding China’s transition from a largely agrarian economy to a rapidly urbanizing, export-driven market economy. The CCP signaled its intent to maintain political stability at all costs with the 1989 massacre of prodemocracy protesters who had gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Following the crackdown, the party tapped Jiang Zemin to replace the relatively moderate Zhao Ziyang as general secretary of the party. -

A PDF of This Newsletter

September 2006 China Human Rights and Subscribe Rule of Law Update View PDF Version United States Congressional-Executive Commission on China Senator Chuck Hagel, Chairman | Representative Jim Leach, Co-Chairman Announcements Hearing: Human Rights and Rule of Law in China The Congressional-Executive Commission on China will hold a full Commission hearing entitled "Human Rights and Rule of Law in China," on Wednesday, September 20, 2006 from 10:00 - 11:30 a.m. in Room 138 of the Dirksen Senate Office Building. Senator Hagel will preside. The witnesses are: ● Jerome A. Cohen, Professor of Law, New York University School of Law ● John Kamm, Executive Director, The Dui Hua Foundation ● Minxin Pei, Director, China Program, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace ● Xiao Qiang, Director, China Internet Project, University of California at Berkeley Update on Rights and Law in China Human Rights Updates Rule of Law Updates All Updates Beijing Court Sentences Journalist Zhao Yan to 3 Years' Imprisonment The Beijing No. 2 Intermediate People's Court acquitted New York Times researcher Zhao Yan of disclosing state secrets on August 25, but sentenced him to three years' imprisonment on an unrelated fraud charge, according to an August 25 New York Times report. On August 26, the China Daily reported that the court also fined Zhao 2,000 yuan (US$250) and ordered him to pay back 20,000 yuan (US$2,500) that it ruled he had acquired through fraud. According to a September 5 Associated Press International report (via the Guardian), on that day Zhao filed an appeal arguing that the prosecution's evidence was insufficient and that the court did not allow a defense witness to testify. -

Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1

Writing on the Wall: Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1 WRITING ON THE WALL Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong November 5, 2016 © 2016 PEN America. All rights reserved. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible. Founded in 1922, PEN America is the largest of more than 100 centers of PEN International. Our strength is in our membership—a nationwide community of more than 4,000 novelists, journalists, poets, essayists, playwrights, editors, publishers, translators, agents, and other writing professionals. For more information, visit pen.org. Cover photograph: Artist Kacey Wong protests the Causeway Bay Books disappearances bound and gagged, sporting a red noose bearing the Chinese characters for "abduction." The sign in his hand says "Hostage is well. " Photo courtesy of Kacey Wong. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 “One Country, Two Systems” Under Threat ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Hong Kong’s Legal Framework -

Speak No Evil: Mass Media Control in Contemporary China

A FREEDOM HOUSE SPECIAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2006 SPEAK NO EVIL MASS MEDIA CONTROL IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA Ashley Esarey Preface In the present era of globalization, access to information embarked on a wide-ranging economic reform campaign and the technology for disseminating it are taking enormous that exploits the benefits of the information age as an leaps forward. These profound advances, embodied in the important engine for growth. The Chinese authorities have Internet, have enabled millions of average citizens, at the same time devoted vast energies to creating businesses, and nongovernmental organizations to share sophisticated ways to control information they deem ideas in a manner unthinkable even a generation ago. politically undesirable. Whether the Chinese Communist At the same time, the democratization of information and Party can maintain its monopoly on power, suppress press the democratizing power of information have not gone freedom, and also achieve its ambitions of economic unnoticed by governments intent on controlling both access modernization over the longer term is open to serious to media and their content. The application of 21st century question. technology—especially its ability to connect people and In order to acquire a deeper understanding of the forces share ideas—has provoked a variety of responses from at work in China’s information sector, Freedom House dictatorships and authoritarian regimes. The friction between commissioned Ashley Esarey, an expert on Chinese media, ordinary people’s desire for diverse sources of information to author a detailed examination of the contemporary tools and opinion and the effort of states to assert control over used by the Chinese authorities to control mass media. -

Six-Monthly Report on Hong Kong January

Six-monthly Report on Hong Kong January - June 2006 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty July 2006 Cm 6891 £5.00 © Crown copyright 2006 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to the Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax 010603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] FOREWORD This is the nineteenth in a series of reports to Parliament on the implementation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong. It covers the period from 1 January to 30 June 2006. I am pleased to present this, my first such report to Parliament, and to affirm HM Government's continuing strong interest in Hong Kong and our commitment to the development of our already flourishing relationship. I am no stranger to Hong Kong. I had the pleasure of visiting there in 1997, 2004 and again last December for the WTO Ministerial meeting, together with the Secretary of State for Trade and Investment, the Secretary of State for International Development and the Minister for Trade. I hope to be able to visit again in my capacity as Foreign Secretary and renew my acquaintance with old friends, as well as make new ones. -

![Transcript Produced from a Tape Recording]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7370/transcript-produced-from-a-tape-recording-4947370.webp)

Transcript Produced from a Tape Recording]

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES HONG KONG: HAPPY WITHOUT DEMOCRACY? A CNAPS Roundtable Luncheon with FRANK CHING SENIOR COLUMNIST SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST The Brookings Institution Washington, DC May 30, 2006 [TRANSCRIPT PRODUCED FROM A TAPE RECORDING] MALLOY TRANSCRIPTION SERVICE 7040 31ST STREET, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20015 (202) 546-6666 PROCEEDINGS DR. BUSH: I am Richard Bush, the director of the Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies here at Brookings, and on behalf of Jeffrey Bader, the director of our China Initiative, and myself, it is our pleasure to welcome you here today for this joint event featuring Frank Ching, our old and good friend. We are not going to abuse Frank's human rights and have him speak before he eats. We are not going to abuse your human rights and have you listen before you eat, but we will get back to that a little bit later. Please enjoy your lunch, and we will get to the substance of the event a little bit later. Until then, bon appétit. [Luncheon break.] DR. BUSH: Ladies and gentlemen, if I could have your attention, please. I hope you have enjoyed the cuisine of Chez Brookings, and now we get to the really good stuff. Frank Ching is an old friend of this Institution. He is one of the leading journalists of East Asia. He has worked for the Far Eastern Economic Review, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and now the South China Morning Post. You can always count on him for insightful commentary on the events of the day in Hong Kong and China, and we are very privileged to have him speak to us today about the current situation in Hong Kong and an important question; that is, what has happened to the demand for democracy? Now that the government of Hong Kong seems to be performing well and the population seems to be satisfied, the concern for the political system and the political process seems to have diminished as an important issue. -

Hong Kong, China: Learning to Belong to a Nation

Downloaded by [ISTEX] at 03:47 06 September 2013 Hong Kong, China The idea of “national identity” is an ambiguous one for Hong Kong. Returned to the national embrace of China on 1 July 1997 after 150 years as a British colony, the concept of national identity and what it means to “belong to a nation” is a matter of great tension and contestation in Hong Kong. Written by three academic specialists on cultural identity, social history, and the mass media, this book explores the processes through which the people of Hong Kong are “learning to belong to a nation” by examining their shifting rela- tionship with the Chinese nation and state in the recent past, present, and future. It considers the complex meanings of and debates over national identity in Hong Kong over the past fifty years, especially during the last decade following the territory’s return to China. In doing so, the book takes a larger, global perspect- ive, exploring what Hong Kong teaches us about potential future transforma- tions of national identity in the world as a whole. Multidisciplinary in approach, Hong Kong, China examines national identity in terms of theory, ethnography, history, the mass media, and survey data, and will appeal to students and scholars of Chinese history, cultural studies, and nationalism. Gordon Mathews teaches in the Department of Anthropology, the Chinese Uni- versity of Hong Kong. Eric Kit-wai Ma teaches in the School of Journalism and Communication, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Tai-lok Lui teaches in Downloaded by [ISTEX] at 03:47 06 September 2013 the Department of Sociology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. -

The Party Transition Will It Bring a New Maturity in Chinese Security Policy? Thomas J

Hoover-CLM-5.qxd 6/5/2003 12:36 PM Page 3 The Party Transition Will It Bring a New Maturity in Chinese Security Policy? Thomas J. Christensen This essay will address three questions relating to the 16th Party Congress.1 First, what do the power transition and the new lineup of leaders mean for the prospect for future flexibility and new thinking in Beijing on key security issues important to U.S.-China relations: Taiwan, the war on terrorism, Iraq and the U.N. Security Council, weapons proliferation, North Korea, etc.? Second, what evidence exists of new thinking more broadly in the younger generations of Chinese foreign policy elites (35–60 years old) who are replacing the generation of Jiang Zemin, Qian Qichen, and retiring generals such as Chi Haotian and Zhang Wannian? Third, what role do these changes play, if any, in the marked recent warming trends in relations between Washington and Beijing? ON THE FIRST QUESTION, I believe the messages are mixed and it is still too soon to tell. Many observers focus on the new leadership of General Secretary Hu Jintao and the relative lack of acrimony in the transition of power. But most still tend to believe that the complete transition will involve years of cautious consolidation for Hu’s new team, as it did for Jiang Zemin in the 1990s.2 An alternative interpreta- tion would be that the real transformation at the 16th Party Congress was more immediate and dramatic and has less to do with Hu than with his predecessor, Jiang Zemin. -

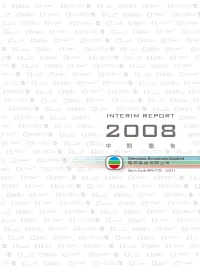

2008 Interim Report

4CSpot + PantoneUV 8422 C IInside_Front_Cover_Eng.ainside_Front_Cover_Eng.ai 99/5/2008/5/2008 111:18:071:18:07 AAMM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K CONTENTS FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 2 CORPORATE INFORMATION 4 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 6 REVIEW OF OPERATIONS OVERVIEW 7 TERRESTRIAL TELEVISION BROADCASTING 7 INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS 9 HONG KONG PAY TV BUSINESS 10 OTHER BUSINESSES 11 FINANCIAL REVIEW 11 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND OTHER INFORMATION 13 FINANCIAL INFORMATION CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEET 18 CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENT 20 CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 21 CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED CASH FLOW STATEMENT 22 NOTES TO THE CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION 23 INDEPENDENT REVIEW REPORT 43 Television Broadcasts Limited Interim Report 2008 1 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Turnover (HK$’mil) 1st Half 2nd Half 2008 2,073 2007 4,326 2006 4,201 YEAR 2005 4,177 2004 3,817 2003 3,311 0 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000 HK$’ mil Profit Attributable to Equity Holders (HK$’mil) 1st Half 2nd Half 2008 503 2007 1,264 2006 1,189 YEAR 2005 1,180 2004 719 2003 441 0 200 400 600 800 1,000 1,200 1,400 HK$’ mil 2 Television Broadcasts Limited Interim Report 2008 Six months ended 30 June 2008 2007 HK$’mil HK$’mil (Unaudited) (Unaudited) Turnover 2,073 1,919 Profit before income tax 605 603 Profit attributable to equity holders of the Company 503 497 Earnings per share HK$1.15 HK$1.14 Interim dividend per share HK$0.30 HK$0.30 Number of issued shares 438,000,000 shares 438,000,000 shares 30 June 31 December 2008 2007 HK$’mil HK$’mil (Unaudited) (Audited) Property, plant and equipment 2,412 1,722 Programmes and film rights 474 461 Trade and other receivables, prepayments and deposits 1,389 1,468 Bank deposits, cash and cash equivalents 1,743 2,141 Net current assets 2,858 3,277 Net assets 5,244 5,369 Gearing 6.83% – Television Broadcasts Limited Interim Report 2008 3 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Sir Run Run SHAW, G.B.M.