Dynamic Range Compression and the Semantic Descriptor Aggressive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Learning to Build Natural Audio Production Interfaces

arts Article Learning to Build Natural Audio Production Interfaces Bryan Pardo 1,*, Mark Cartwright 2 , Prem Seetharaman 1 and Bongjun Kim 1 1 Department of Computer Science, McCormick School of Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA 2 Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University, New York, NY 10003, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 July 2019; Accepted: 20 August 2019; Published: 29 August 2019 Abstract: Improving audio production tools provides a great opportunity for meaningful enhancement of creative activities due to the disconnect between existing tools and the conceptual frameworks within which many people work. In our work, we focus on bridging the gap between the intentions of both amateur and professional musicians and the audio manipulation tools available through software. Rather than force nonintuitive interactions, or remove control altogether, we reframe the controls to work within the interaction paradigms identified by research done on how audio engineers and musicians communicate auditory concepts to each other: evaluative feedback, natural language, vocal imitation, and exploration. In this article, we provide an overview of our research on building audio production tools, such as mixers and equalizers, to support these kinds of interactions. We describe the learning algorithms, design approaches, and software that support these interaction paradigms in the context of music and audio production. We also discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the interaction approach we describe in comparison with existing control paradigms. Keywords: music; audio; creativity support; machine learning; human computer interaction 1. Introduction In recent years, the roles of producer, engineer, composer, and performer have merged for many forms of music (Moorefield 2010). -

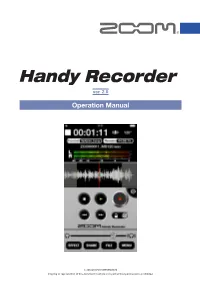

Zoom Handy Recorder App Operations Manual (13 MB Pdf)

ver. 2.0 Operation Manual © 2014 ZOOM CORPORATION Copying or reproduction of this document in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. Contents Introduction‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 3 Copyrights‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 3 Main Screen ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 4 Landscape mode (new in ver. 2.0)‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 5 Recording‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 6 Pausing recording‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 6 Adjusting the recording level‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 7 Setting the recording format‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 7 Muting the input‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 8 Adding recordings (landscape mode only) (new in ver. 2.0)‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 9 Using mid-side recording ( series MS mic only feature)‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 11 Setting mid-side monitoring‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 11 Playback‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 12 Selecting‥and‥playing‥files‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 12 Pausing playback‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 13 Playing‥files‥from‥the‥FILE‥screen‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 13 Adjusting the playback level‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 14 Repeating playback of an interval (new in ver. 2.0) ‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 14 Editing‥and‥deleting‥files‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 15 Dividing‥files‥(landscape‥mode‥only)‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ -

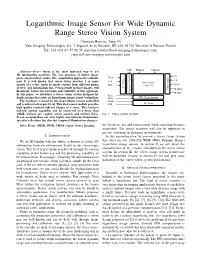

Logarithmic Image Sensor for Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System

Logarithmic Image Sensor For Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System Christian Bouvier, Yang Ni New Imaging Technologies SA, 1 Impasse de la Noisette, BP 426, 91370 Verrieres le Buisson France Tel: +33 (0)1 64 47 88 58 [email protected], [email protected] NEG PIXbias COLbias Abstract—Stereo vision is the most universal way to get 3D information passively. The fast progress of digital image G1 processing hardware makes this computation approach realizable Vsync G2 Vck now. It is well known that stereo vision matches 2 or more Control Amp Pixel Array - Scan Offset images of a scene, taken by image sensors from different points RST - 1280x720 of view. Any information loss, even partially in those images, will V Video Out1 drastically reduce the precision and reliability of this approach. Exposure Out2 In this paper, we introduce a stereo vision system designed for RD1 depth sensing that relies on logarithmic image sensor technology. RD2 FPN Compensation The hardware is based on dual logarithmic sensors controlled Hsync and synchronized at pixel level. This dual sensor module provides Hck H - Scan high quality contrast indexed images of a scene. This contrast indexed sensing capability can be conserved over more than 140dB without any explicit sensor control and without delay. Fig. 1. Sensor general structure. It can accommodate not only highly non-uniform illumination, specular reflections but also fast temporal illumination changes. Index Terms—HDR, WDR, CMOS sensor, Stereo Imaging. the details are lost and consequently depth extraction becomes impossible. The sensor reactivity will also be important to prevent saturation in changing environments. -

Psychoacoustics Perception of Normal and Impaired Hearing with Audiology Applications Editor-In-Chief for Audiology Brad A

PSYCHOACOUSTICS Perception of Normal and Impaired Hearing with Audiology Applications Editor-in-Chief for Audiology Brad A. Stach, PhD PSYCHOACOUSTICS Perception of Normal and Impaired Hearing with Audiology Applications Jennifer J. Lentz, PhD 5521 Ruffin Road San Diego, CA 92123 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pluralpublishing.com Copyright © 2020 by Plural Publishing, Inc. Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Garamond by Flanagan’s Publishing Services, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by McNaughton & Gunn, Inc. All rights, including that of translation, reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution, or information storage and retrieval systems without the prior written consent of the publisher. For permission to use material from this text, contact us by Telephone: (866) 758-7251 Fax: (888) 758-7255 e-mail: [email protected] Every attempt has been made to contact the copyright holders for material originally printed in another source. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will gladly make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lentz, Jennifer J., author. Title: Psychoacoustics : perception of normal and impaired hearing with audiology applications / Jennifer J. Lentz. Description: San Diego, CA : Plural Publishing, -

Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2

The Communications Edge™ Tech-note Author: Robert E. Watson Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2 Part 1 of this article reviews receiver mea- the receiver can process acceptably. In sim- NF is the receiver noise figure in dB surements which, taken as a group, describe plest terms, it is the difference in dB This dynamic range definition has the receiver dynamic range. Part 2 introduces between the inband 1-dB compression point advantage of being relatively easy to measure comprehensive measurements that attempt and the minimum-receivable signal level. without ambiguity but, unfortunately, it to characterize a receiver’s dynamic range as The compression point is obvious enough; assumes that the receiver has only a single a single number. however, the minimum-receivable signal signal at its input and that the signal is must be identified. desired. For deep-space receivers, this may be COMPREHENSIVE MEASURE- a reasonable assumption, but the terrestrial MENTS There are a number of candidates for mini- mum-receivable signal level, including: sphere is not usually so benign. For specifi- The following receiver measurements and “minimum-discernable signal” (MDS), tan- cation of general-purpose receivers, some specifications attempt to define overall gential sensitivity, 10-dB SNR, and receiver interfering signals must be assumed, and this receiver dynamic range as a single number noise floor. Both MDS and tangential sensi- is what the other definitions of receiver which can be used both to predict overall tivity are based on subjective judgments of dynamic range do. receiver performance and as a figure of merit signal strength, which differ significantly to compare competing receivers. -

For the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products (Ba5105)

Technical Documentation Microphone Handbook For the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products Brüel&Kjær B K WORLD HEADQUARTERS: DK-2850 Nærum • Denmark • Telephone: +4542800500 •Telex: 37316 bruka dk • Fax: +4542801405 • e-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.bk.dk BA 5105 –12 Microphone Handbook Revision February 1995 Brüel & Kjær Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products BA 5105 –12 Microphone Handbook Trademarks Microsoft is a registered trademark and Windows is a trademark of Microsoft Cor- poration. Copyright © 1994, 1995, Brüel & Kjær A/S All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without prior consent in writing from Brüel & Kjær A/S, Nærum, Denmark. 0 − 2 Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products Brüel & Kjær Microphone Handbook Contents 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 – 1 1.1 About the Microphone Handbook............................................................................... 1 – 2 1.2 About the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products.................................................. 1 – 2 1.3 The Microphones ......................................................................................................... 1 – 2 1.4 The Preamplifiers........................................................................................................ 1 – 8 1 2. Prepolarized Free-field /2" Microphone Type 4188....................... 2 – 1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ -

TA-1VP Vocal Processor

D01141720C TA-1VP Vocal Processor OWNER'S MANUAL IMPORTANT SAFETY PRECAUTIONS ªª For European Customers CE Marking Information a) Applicable electromagnetic environment: E4 b) Peak inrush current: 5 A CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER- Disposal of electrical and electronic equipment SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO (a) All electrical and electronic equipment should be QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. disposed of separately from the municipal waste stream via collection facilities designated by the government or local authorities. The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol, within equilateral triangle, is intended to (b) By disposing of electrical and electronic equipment alert the user to the presence of uninsulated correctly, you will help save valuable resources and “dangerous voltage” within the product’s prevent any potential negative effects on human enclosure that may be of sufficient health and the environment. magnitude to constitute a risk of electric (c) Improper disposal of waste electrical and electronic shock to persons. equipment can have serious effects on the The exclamation point within an equilateral environment and human health because of the triangle is intended to alert the user to presence of hazardous substances in the equipment. the presence of important operating and (d) The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the appliance. symbol, which shows a wheeled bin that has been crossed out, indicates that electrical and electronic equipment must be collected and disposed of WARNING: TO PREVENT FIRE OR SHOCK separately from household waste. HAZARD, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS APPLIANCE TO RAIN OR MOISTURE. -

Loudness Standards in Broadcasting. Case Study of EBU R-128 Implementation at SWR

Loudness standards in broadcasting. Case study of EBU R-128 implementation at SWR Carbonell Tena, Damià Curs 2015-2016 Director: Enric Giné Guix GRAU EN ENGINYERIA DE SISTEMES AUDIOVISUALS Treball de Fi de Grau Loudness standards in broadcasting. Case study of EBU R-128 implementation at SWR Damià Carbonell Tena TREBALL FI DE GRAU ENGINYERIA DE SISTEMES AUDIOVISUALS ESCOLA SUPERIOR POLITÈCNICA UPF 2016 DIRECTOR DEL TREBALL ENRIC GINÉ GUIX Dedication Für die Familie Schaupp. Mit euch fühle ich mich wie zuhause und ich weiß dass ich eine zweite Familie in Deutschland für immer haben werde. Ohne euch würde diese Arbeit nicht möglich gewesen sein. Vielen Dank! iv Thanks I would like to thank the SWR for being so comprehensive with me and for letting me have this wonderful experience with them. Also for all the help, experience and time given to me. Thanks to all the engineers and technicians in the house, Jürgen Schwarz, Armin Büchele, Reiner Liebrecht, Katrin Koners, Oliver Seiler, Frauke von Mueller- Rick, Patrick Kirsammer, Christian Eickhoff, Detlef Büttner, Andreas Lemke, Klaus Nowacki and Jochen Reß that helped and advised me and a special thanks to Manfred Schwegler who was always ready to help me and to Dieter Gehrlicher for his comprehension. Also to my teacher and adviser Enric Giné for his patience and dedication and to the team of the Secretaria ESUP that answered all the questions asked during the process. Of course to my Catalan and German families for the moral (and economical) support and to Ema Madeira for all the corrections, revisions and love given during my stay far from home. -

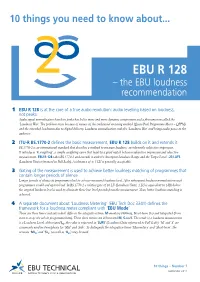

EBU R 128 – the EBU Loudness Recommendation

10 things you need to know about... EBU R 128 – the EBU loudness recommendation 1 EBU R 128 is at the core of a true audio revolution: audio levelling based on loudness, not peaks Audio signal normalisation based on peaks has led to more and more dynamic compression and a phenomenon called the ‘Loudness War’. The problem arose because of misuse of the traditional metering method (Quasi Peak Programme Meter – QPPM) and the extended headroom due to digital delivery. Loudness normalisation ends the ‘Loudness War’ and brings audio peace to the audience. 2 ITU-R BS.1770-2 defines the basic measurement, EBU R 128 builds on it and extends it BS.1770-2 is an international standard that describes a method to measure loudness, an inherently subjective impression. It introduces ‘K-weighting’, a simple weighting curve that leads to a good match between subjective impression and objective measurement. EBU R 128 takes BS.1770-2 and extends it with the descriptor Loudness Range and the Target Level: -23 LUFS (Loudness Units referenced to Full Scale). A tolerance of ± 1 LU is generally acceptable. 3 Gating of the measurement is used to achieve better loudness matching of programmes that contain longer periods of silence Longer periods of silence in programmes lead to a lower measured loudness level. After subsequent loudness normalisation such programmes would end up too loud. In BS.1770-2 a relative gate of 10 LU (Loudness Units; 1 LU is equivalent to 1dB) below the ungated loudness level is used to eliminate these low level periods from the measurement. -

Signal-To-Noise Ratio and Dynamic Range Definitions

Signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range definitions The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Dynamic Range (DR) are two common parameters used to specify the electrical performance of a spectrometer. This technical note will describe how they are defined and how to measure and calculate them. Figure 1: Definitions of SNR and SR. The signal out of the spectrometer is a digital signal between 0 and 2N-1, where N is the number of bits in the Analogue-to-Digital (A/D) converter on the electronics. Typical numbers for N range from 10 to 16 leading to maximum signal level between 1,023 and 65,535 counts. The Noise is the stochastic variation of the signal around a mean value. In Figure 1 we have shown a spectrum with a single peak in wavelength and time. As indicated on the figure the peak signal level will fluctuate a small amount around the mean value due to the noise of the electronics. Noise is measured by the Root-Mean-Squared (RMS) value of the fluctuations over time. The SNR is defined as the average over time of the peak signal divided by the RMS noise of the peak signal over the same time. In order to get an accurate result for the SNR it is generally required to measure over 25 -50 time samples of the spectrum. It is very important that your input to the spectrometer is constant during SNR measurements. Otherwise, you will be measuring other things like drift of you lamp power or time dependent signal levels from your sample. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick.