Our Unswerving Loyalty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

National Security and Local Police

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE NATIONAL SECURITY AND LOCAL POLICE Michael Price Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S LIBERTY AND NATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S PUBLICATIONS Red cover | Research reports offer in-depth empirical findings. Blue cover | Policy proposals offer innovative, concrete reform solutions. White cover | White papers offer a compelling analysis of a pressing legal or policy issue. -

James Daffern 15/09/2020, 21�09

Spotlight: JAMES DAFFERN 15/09/2020, 2109 JAMES DAFFERN C S A 3rd Floor Joel House, 17-21 Garrick Street, London WC2E 9BL Phone: 020-7420 9351 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk HARVEY VOICES 49 Greek Street, London W1D 4EG Phone: 020 7952 4361 Mobile: 07739 902784 Photo: Jennie Scott E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.harveyvoices.co.uk Location: Greater London, Appearance: White, England, United Scandinavian, Kingdom Eastern Height: 6' (182cm) European Weight: 13st. 7lb. (86kg) Other: Equity Playing Age: 40 - 50 years Eye Colour: Blue Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Short About me: Television Television, Andrew Wallace, PROFESSOR T, Eagle Eye Productions, Indra Siera Television, Jim Bonning, CASUALTY, BBC, Various Television, One Eyed Marc, BIRDS OF A FEATHER, ITV, Martin Dennis Television, Leon, X COMPANY, CBC Television/Sony Pictures Television Television, Ben Owens, DOCTORS (NINE EPS), BBC, Various Television, Zac Glazerbrook, CUFFS, BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions, Kieron Hawkes Television, Natie, RAISED BY WOLVES, C4, Mitchell Altieri Television, Bruce, FLYING HIGH, ZDF, Stephen Bartmann Television, Andrew Hayden, HUNTED, Kudos/HBO/BBC, Daniel Percival/James Strong Television, Ray Keats, WATERLOO ROAD, Shed Productions, Fraser Macdonald Television, Lucas North in Flashback, SPOOKS, BBC Television, Edward Hall Television, Paul Walsh, HOME TIME, BBC Television, Christine Gernon Television, Nathan, RIVER CITY, BBC Television, Semi regular Television, Jimmy Barrett, THE ROYAL, Yorkshire Television, -

Spooks Returns to Dvd

A BAPTISM OF FIRE FOR THE NEW TEAM AS SPOOKS RETURNS TO DVD SPOOKS: SERIES NINE AVALIABLE ON DVD FROM 28TH FEBRUARY 2011 “Who doesn’t feel a thrill of excitement when a new series of Spooks hits our screens?” Daily Mail “It’s a tribute to Spooks’ staying power that after eight years we still care so much” The Telegraph BAFTA Award‐winning British television spy drama Spooks is back for its ninth knuckle‐clenching series and is available on DVD from 28th February 2011 courtesy of Universal Playback. Filled with spy‐tastic extra features, the DVD is a must for any die‐hard Spooks fan. The ninth series of the critically acclaimed Spooks, is filled with dramatic revelations and a host of new characters ‐ Sophia Myles (Underworld, Doctor Who), Max Brown (Mistresses, The Tudors), Iain Glen (The Blue Room, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), Simon Russell Beale (Much Ado About Nothing, Uncle Vanya) and Laila Rouass (Primeval, Footballers’ Wives). Friendships will be tested and the depth of deceit will lead to an unprecedented game of cat and mouse and the impact this has on the team dynamic will have viewers enthralled. Follow the team on a whirlwind adventure tracking Somalian terrorists, preventing assassination attempts, avoiding bomb efforts and vicious snipers, and through it all face the personal consequences of working for the MI5. The complete Spooks: Series 9 DVD boxset contains never before seen extras such as a feature on The Cost of Being a Spy and a look at The Downfall of Lucas North. Episode commentaries with the cast and crew will also reveal secrets that have so far remained strictly confidential. -

Policing Terrorism Gary Lafree

Ideas in POLICE American FOUNDATION Number 15 Policing July 2012 Policing Terrorism Gary LaFree lthough terrorism has past. However, some optimism This balance between being much in common is provided by the fact that the effective in counterterrorism A with ordinary crime strong connections to community efforts and maintaining the trust (LaFree and Dugan 2004), it that produce the best results of the community should not be also raises unique challenges for for policing in general may also taken lightly but in some ways policing. Perhaps the greatest be the same characteristics that resembles the challenges police challenges center on how to are most useful in preventing have long faced in responding use scarce police resources to terrorist attacks and responding to crimes that require proactive fight crimes that are relatively to those that are carried out. At rather than reactive methods. uncommon, that have national the same time, providing support I divide this essay into four and sometimes international for counterterrorism must be parts. In part one, I consider the implications, and that require done by local police in such a frequency and characteristics of intelligence that may be limited way that it does not erode their terrorist attacks on the United or altogether unavailable at the effectiveness in communities. States, especially since 9/11. In local and state levels. But despite these challenges, it is hard to Ideas in American Policing presents commentary and insight from leading crimi- imagine any effective national nologists on issues of interest to scholars, practitioners, and policy makers. The policy on preventing terrorism papers published in this series are from the Police Foundation lecture series of the same name. -

Spies: the Rise and Fall of the KGB in America by John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr and Alexander Vassiliev: Review

Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America By John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr and Alexander Vassiliev: review Spies by Haynes, Klehr and Vassiliev proves that the KGB’s infiltration of America started earlier and went deeper than we thought, finds Andrew Lownie By Andrew Lownie Published: 5:50AM BST 28 Jun 2009 A common perception is that, both before and after the Second World War, the British Establishment was penetrated by Soviet spies (most notably by the Cambridge Spy Ring) while America somehow escaped infiltration. This important new book, however, which is based on archival material – a rare luxury for intelligence historians – shows the huge extent of Soviet espionage activity in the United States during the 20th century. The authors estimate that from the Twenties more than 500 Americans from all walks of life, including many Ivy League graduates and Oxford Rhodes Scholars, were recruited to assist Soviet intelligence agencies, particularly in the State Department and America’s first intelligence agency, the OSS. John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr have previously collaborated on books about the Venona spy intercepts and American Communism. Their co-author Alexander Vassiliev, a Russian journalist and former intelligence officer, collaborated on The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America. That book was based on controlled Russian intelligence documents, access to which was negotiated during a moment of Glasnost in the Nineties with a view to supplementing the KGB pension fund, championing Russian intelligence successes and creating a bit of disinformation mischief. What hadn’t been known until recently is that while working on The Haunted Wood, Vassiliev had transcribed and summarised innumerable KGB documents which he had smuggled out with him – more than 1,000 pages of notes – when he began a new life in America. -

I-STRUCTURE of the LANGUAGE and VOCABULARY Choose the Best Answer : 1- She Always Wears the ---Fashion. A-Recent B-Recentl

I-STRUCTURE OF THE LANGUAGE AND VOCABULARY Choose the best answer : 1- She always wears the -------- fashion. A-recent B-recently C-last D-latest 2- Everybody has had -------- own experience. A-there B-their C-they’re D-its 3- I couldn’t remember all -------- I had seen. A-Æ B-what C-where D-when 4- Why not -------- at home using all the modern technology ? A-study B-to be studying C-studying D-to study 5- I love detective stories but my husband hates -------- of novel. A-the kind B-the kinds C-these kinds D-this kind 6- Neither you -------- will depend on our parents. A-either me B-neither me C-nor I D-either I 7- -------- I’m saying is only the truth ! A-which B-what C-that D-this 8- There is no reason -------- you shouldn’t do it. A-what B-why C-which D-for 9- Thank you very much -------- my letter so quickly. A-for answering B-to answering C-to answer D-answering 10- -------- later, the reception would have been ruined. A-was Lyndsay arrived B-Lyndsay has arrived C-has Lydsay arrived D-had Lyndsay arrived 11- I am really motivated -------- something. A-to do B-doing C-about doing D-for doing 12- She suggested -------- to Madrid. A-him to go B-him going C-that he should go D-he goes 13- You may have these cakes -------- there are some left for the rest of the group. A-even if B-provided C-nonetheless D-whereas 14- The crisis we all know today will probably deter consumers -------- buying. -

A Season of Spooks and Style – Trick Or Treat Yourself – CREATE a DEVILISH DINING SPACE with THEMED DÉCOR

HALLOWEEN 2019 A season of spooks and style – trick or treat yourself – CREATE A DEVILISH DINING SPACE WITH THEMED DÉCOR 1. Host 3. Exclusive! Our large lanterns are only available when you Host 1. Spider Web Tealight Pair a Party. Glass. 10 cm h. P92816 £19.95 5. 6. 2. GloLite by PartyLite® Mystery Potion Jar Candle Two wicks, yellow wax. Burn time: 50-60 hrs. 2. 12 cm w. G26783E £24.95 3. Tapers - Unscented Six piece tray. 7-8 hrs. 25 cm h. Orange P07301 £10.95 4. Black Cat Tealight Holder Ceramic. 24 cm h. P9415 £22.95 7. 4. 10. 5. Elevated Candle Holder Centerpiece 8. Metal. Includes 4 glass cups and 4 magnetic metal taper holders (In cups: votive, tealight; On frame: 5x10 cm pillar, large tealight; In magnetic holders on 9. frame: taper). Frame with cups: 15 cm h, 36 cm w. P93375 £44.95 6. Host Only: Hammered Minaret Don’t be afraid of Lantern – Large the dark! They transform Metal and glass. Includes metal jar stand plus in low light 3-tealight tree (tealight, jar, large tealight, pillar). 11. With ring down: 59 cm h, 23 cm w. P93381 £59.95 7. Spiced Pumpkin 3-Wick Jar Candle Burn time: 25-45 hrs. G73B842E £22.95 8. Perfect Pumpkin Jar Candle 11. Spooky Shadow Faces Tealight Holder Pair Lidded ceramic pumpkin filled with Spiced Pumpkin Porcelain. 8 cm h, 9 cm w. 13. fragrance. 11 cm h, 9 cm w. Burn time: 30-40 hrs. P93394 £24.95 12. P93405E £19.95 12. -

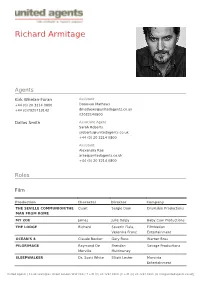

Richard Armitage

Richard Armitage Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE SEVILLE COMMUNION/THE Quart Sergio Dow Drumskin Productions MAN FROM ROME MY ZOE James Julie Delpy Baby Cow Productions THE LODGE Richard Severin Fiala, FilmNation Veronika Franz Entertainment OCEAN'S 8 Claude Becker Gary Ross Warner Bros PILGRIMAGE Raymond De Brendan Savage Productions Merville Muldowney SLEEPWALKER Dr. Scott White Elliott Lester Marvista Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company BRAIN ON FIRE Tom Cahalan Gerard Barrett Broad Green Pictures ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING King Oleron James Bobin Walt Disney Pictures GLASS URBAN AND THE SHED CREW Chop Candida Brady Blenheim Films THE HOBBIT: THE BATTLE OF Thorin Peter Jackson MGM THE FIVE ARMIES Oakenshield INTO THE STORM Gary Morris Steven Quale Broken Road/New Line THE HOBBIT - THE DESOLATION Thorin Peter Jackson MGM OF SMAUG Oakenshield THE HOBBIT - AN UNEXPECTED Thorin Peter Jackson MGM JOURNEY Oakenshield CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST Heinz Kruger Joe Johnston Marvel AVENGER CLEOPATRA Epiphanes Frank Roddan Alexandria Films FROZEN Steven Juliet McKoen Liminal Films MACBETH Angus -

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other Books in the Current Controversies Series

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other books in the Current Controversies series: The Abortion Controversy Issues in Adoption Alcoholism Marriage and Divorce Assisted Suicide Medical Ethics Biodiversity Mental Health Capital Punishment The Middle East Censorship Minorities Child Abuse Nationalism and Ethnic Civil Liberties Conflict Computers and Society Native American Rights Conserving the Environment Police Brutality Crime Politicians and Ethics Developing Nations Pollution The Disabled Prisons Drug Abuse Racism Drug Legalization The Rights of Animals Drug Trafficking Sexual Harassment Ethics Sexually Transmitted Diseases Family Violence Smoking Free Speech Suicide Garbage and Waste Teen Addiction Gay Rights Teen Pregnancy and Parenting Genetic Engineering Teens and Alcohol Guns and Violence The Terrorist Attack on Hate Crimes America Homosexuality Urban Terrorism Illegal Drugs Violence Against Women Illegal Immigration Violence in the Media The Information Age Women in the Military Interventionism Youth Violence Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Louise I. Gerdes, Book Editor Daniel Leone,President Bonnie Szumski, Publisher Scott Barbour, Managing Editor Helen Cothran, Senior Editor CURRENT CONTROVERSIES San Diego • Detroit • New York • San Francisco • Cleveland New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich © 2004 by Greenhaven Press. Greenhaven Press is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Greenhaven® and Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. For more information, contact Greenhaven Press 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Or you can visit our Internet site at http://www.gale.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. -

Melita Norwood Papers Circa 1902-2003

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0g50328j No online items Register of the Melita Norwood papers circa 1902-2003 Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Archives Staff Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2013 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Melita Norwood 2010C5 1 papers circa 1902-2003 Collection Summary Title: Melita Norwood papers Date (inclusive): circa 1902-2003 Creator: Norwood, Melita, 1912-2005. Collection Number: 2010C5 Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Collection Size: 2 manuscript boxes (0.8 linear feet) Abstract: Letters, notes, interview summaries, biographical and genealogical data, personal documents, printed matter, and photographs related to Soviet nuclear research espionage in Great Britain, the communist movement in Great Britain, and family affairs. Includes papers of Hilary Norwood, husband of Melita Norwood. Language of the materials: The collection is in English. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Access The collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Melita Norwood papers, [Box no.], Hoover Institution Archives Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 2010. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ).