Language and Conflict in English Literature from Gaskell to Tressell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

Mapping Gissing's Workers in the Dawn

The Gissing Journal Volume XLVI, Number 4, 0ctober 2010 “More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me.” Commonplace Book Mapping Gissing’s Workers in the Dawn RICHARD DENNIS University College London Making maps of novels has a long tradition. Some stories, such as Treasure Island, come with their own maps. Closer to Gissing’s London, Arthur Morrison’s Child of the Jago (1896) featured a frontispiece map of the “Jago,” plotting out a street pattern almost identical to that of the real “Nichol” in Shoreditch, but substituting Morrison’s names: the real “Mead Street” became “Honey Lane,” “Boundary Street” became “Edge Lane,” and so forth. Other novels received maps courtesy of their publishers – OUP’s “A Map of Mrs Dalloway’s London” and Penguin’s “Central London in the Mid-Twenties” are just simplified street maps of 1920s London to help readers unfamiliar with the metropolis to follow the routes of characters in Mrs Dalloway as they weave their way across the West End.1 Blackwell’s map of “The London of Mrs Dalloway” is annotated with numbered references to incidents in the text. But none of these maps plot the characters’ walks. They merely mark locations that would allow readers to construct their own geographies of the novel.2 At the other analytical extreme are Franco Moretti’s maps of novels by Dickens, Balzac, Flaubert, and Conan Doyle, some simply marking the locations of key events or characters’ homes, but others more abstractly identifying clusters of characters in topographical and social space to produce Venn diagrams of overlapping or interpenetrating social worlds superimposed on maps of London and Paris, or charting, in the case of Our Mutual Friend, the movement of the narrative from one part of the city to another through successive monthly instalments.3 As important are the blank spaces that emerge and the divides that are rarely crossed. -

Workers in the Dawn by George Gissing #0HSQPDG5LER #Free

Workers in the Dawn George Gissing Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Workers in the Dawn George Gissing Workers in the Dawn George Gissing George Robert Gissing was an English novelist who published 23 novels between 1880 and 1903. Gissing also worked as a teacher and tutor throughout his life. He published his first novel, Workers in the Dawn, in 1880. His best known novels, which are published in modern editions, include The Nether World (1889), New Grub Street (1891), and The Odd Women (1893) (font: Wikipedia). Download Workers in the Dawn ...pdf Read Online Workers in the Dawn ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Workers in the Dawn George Gissing From reader reviews: Ruth Brown: This Workers in the Dawn book is absolutely not ordinary book, you have it then the world is in your hands. The benefit you receive by reading this book is actually information inside this publication incredible fresh, you will get details which is getting deeper a person read a lot of information you will get. This kind of Workers in the Dawn without we understand teach the one who looking at it become critical in considering and analyzing. Don't always be worry Workers in the Dawn can bring whenever you are and not make your bag space or bookshelves' turn into full because you can have it with your lovely laptop even phone. This Workers in the Dawn having good arrangement in word and layout, so you will not feel uninterested in reading. Charles Montiel: Reading a guide can be one of a lot of activity that everyone in the world likes. -

Post-Authenticity: Literary Dialect and Realism in Victorian and Neo-Victorian Social Novels

1 Post-Authenticity: Literary Dialect and Realism in Victorian and Neo-Victorian Social Novels By: Suzanne Pickles A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of English July 2018 2 Abstract This thesis considers what a post-authenticity approach to literary dialect studies should be. Once we have departed from the idea of literary dialect studies being engaged in ascertaining whether or not the fictional representation of nonstandard speech varieties can be matched with those same varieties in the external world, how should we study the dialect we find in novels? I argue that literary dialect studies should be placed within critical work on the realist novel, since the representation of speech, like the broader field of realism, aims to reflect an external world, one with which the reader can identify. This, as yet, has not been done. My approach is to place greater emphasis on the role of the reader. I consider the ways in which writers use literary dialect to manage readers’ responses to characters, and the nature of those responses. I give a close reading of Victorian and neo-Victorian novels to show that, whilst the subject matter of these works has changed over time to suit a modern readership, the dialect representation – its form and the attitudes to language usage it communicates – is conservative. Referring to recent surveys, and through my own research with real readers, I show that nonstandard speakers are still regarded as less well-educated and of a lower social class than those who speak Standard English. -

ISSN 0017-0615 the GISSING JOURNAL “More Than Most Men Am I Dependent on Sympathy to Bring out the Best That Is in Me.”

ISSN 0017-0615 THE GISSING JOURNAL “More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me.” – George Gissing’s Commonplace Book. ********************************** Volume XXX, Number 2 April, 1994 ********************************** Contents London Homes and Haunts of George Gissing: An 1 Unpublished Essay by A. C. Gissing, edited by Pierre Coustillas and Xavier Pétremand The Critical Response to Gissing and Commentary about 15 him in the Chicago Evening Post (concluded), by Robert L. Selig Book Reviews, by Bouwe Postmus, Jacob Korg and Pierre Coustillas 22 Thesis Abstract, by Chandra Shekar Dubey 24 Notes and News 36 Recent Publications 39 -- 1 -- London Homes and Haunts of George Gissing An Unpublished Essay by A. C. Gissing Edited by Pierre Coustillas and Xavier Pétremand In our introduction to “George Gissing and War,” which was printed in the January 1992 number of this journal, we mentioned the existence of two other unpublished essays by Alfred Gissing, “Frederic Harrison and George Gissing” and “London Homes and Haunts of George Gissing.” The three of them were doubtless written in the 1930s when he lived with his sole surviving aunt Ellen at Croft Cottage. Alfred did not date these essays, but they all carry his address of the period – Barbon, Westmorland, via Carnforth. Although they were less ambitious pieces than the articles he published in the National Review in August 1929 and January 1937, they were doubtless intended for publication; yet there is no evidence available that their author tried to find them a home in magazines such as T.P.’s Weekly or John o’ London’s Weekly, which sought to offer cultural entertainment and information to a public that cared for literature and any easily digestible comment on writers’ lives and works. -

THE IMAGINATION of CLASS Bivona Fm 3Rd.Qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page Ii Bivona Fm 3Rd.Qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page Iii

Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page i THE IMAGINATION OF CLASS Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page ii Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page iii THE IMAGINATION OF CLASS Masculinity and the Victorian Urban Poor Dan Bivona and Roger B. Henkle The Ohio State University Press Columbus Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bivona, Daniel. The imagination of class : masculinity and the Victorian urban poor / Dan Bivona, Roger B. Henkle. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-1019-8 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-9096-5 (cd-rom) 1. English prose literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Urban poor—Great Britain—History—19th century. 3. Social classes in literature. 4. Masculinity in lit- erature. 5. Sex role in literature. 6. Poverty in literature. 7. Poor in literature. I. Henkle, Roger B. II. Title. PR878.P66B58 2006 828’.80809352624—dc22 2005030683 Cover design by Dan O’Dair. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Printed by Thomson Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page v In Memory of Roger B. Henkle 1937–1991 Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page vi Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page vii - CONTENTS - Preface ix Foreword by -

Henry Ryecroft Meets Henry Maitland: George Gissing in and on Bloomsbury

Henry Ryecroft meets Henry Maitland: George Gissing in and on Bloomsbury Richard Dennis Dept of Geography, UCL [email protected] Introduction George Gissing is not normally associated with Bloomsbury. He is a man of the slums, or on the margins, or maybe a cynical observer of the nouveau riche, but never a Bloomsbury academic or intellectual. And yet Bloomsbury featured prominently in both his own life and his work. In this paper I want to focus on (1) Gissing’s relationship with the British Museum; (2) his use of the streets and squares of Bloomsbury; (3) his own residence in various lodgings in Bloomsbury and how this translated into his novels; and (4) to reflect on his overall personification of Bloomsbury, including scenes from his novels that were apparently NOT based on his own particular experiences. The British Museum Gissing obtained his reader’s ticket for the British Museum Reading Room in November 1877, the day after his 20th birthday.1 In New Grub Street Edwin Reardon applies for his reader’s ticket on his 21st birthday, for which he needed “the signature of some respectable householder”.2 Gissing himself seems not to have had any difficulty getting his ticket, notwithstanding both his youth (he must have misrepresented his age and claimed to be 21) and his recently obtained criminal record.3 The British Museum was central to Gissing’s life in London, both as an impoverished writer, as a source of heat, light and running water as well as a site for research, and as a classical scholar. -

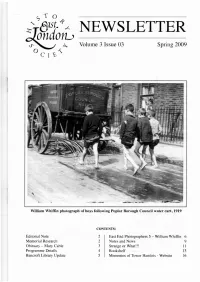

Onion ) Volume 3 Issue 03 Spring 2009

T 0 ast P NEWSLETTER onion_) Volume 3 Issue 03 Spring 2009 /C, C William Whiffin photograph of boys following Poplar Borough Council water cart, 1919 CONTENTS: Editorial Note 2 East End Photographers 5 — William Whiffin 6 Memorial Research 2 Notes and News 9 Obituary — Mary Cable 3 Strange or What!!! 11 Programme Details 4 Bookshelf 13 Bancroft Library Update 5 Mementos of Tower Hamlets - Website 16 ELVIS Newsletter Spring 2009 Editorial Note: MEMORIAL RESEARCH I At the Annual General Meeting, held on 30th October 2008, the following Committee Doreen and Diane Kendall, with Doreen members were re-elected: Philip Mernick, Osborne and other volunteers continue their Chairman, Doreen Kendall, Secretary, Harold work in the Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park Mernick, Membership, David Behr, meticulously researching graves and recording Programme, Ann Sansom, Doreen Osborne, memorial inscriptions. They would welcome and Rosemary Taylor. All queries regarding any help members can offer. Their work has membership should be addressed to Harold grown into a project of enormous proportions Mernick, 42 Campbell Road, Bow, London E3 and complexity, with an impressive database 4DT. of graves researched, with illustrations attached. Enquiries to Doreen Kendall, 20 Puteaux House, Cranbrook Estate, Bethnal Green, Unfortunately, due to pressure of work, London E2 ORF, Tel: 0208 981 7680, or Philip Doreen and Diane cannot undertake any Memick, email: philmernicks com research on behalf of individuals, but would welcome any information that has been Check out the History Society's website at uncovered through personal searches. Meet www.eastIondonhistory.org.uk. them in the Cemetery Park on the 2nd Sunday of every month at 2 pm, where you can Our grateful thanks go to all the contributors receive helpful advice and suggestions on the of this edition of the newsletter, with a special best way to conduct your searches. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Dorothy Forster: a Novel by Walter Besant 2 New From$27.95

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Dorothy Forster: a novel by Walter Besant 2 New from$27.95. Paperback$31.75. 6 New from$31.75. Title:Dorothy Forster. A novel. Publisher:British Library, Historical Print EditionsThe British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. It is one of the world's largest research libraries holding over 150 million items in all known languages and formats: books, journals, newspapers, sound recordings, patents, maps, stamps, …4.2/5(2)Format: PaperbackAuthor: Walter BesantDorothy Forster: A Novel, Volume 1...: Besant, Walter ...https://www.amazon.com/Dorothy-Forster-Novel-Walter- Besant/dp/1279022167Besant Walter Dorothy Forster: A Novel, Volume 1... Paperback – March 29, 2012 by Walter Besant (Author)Author: Walter BesantFormat: PaperbackImages of Dorothy Forster A Novel by Walter Besant bing.com/imagesSee allSee all imagesDorothy Forster. a Novel.: Besant, Walter: 9781241480479 ...https://www.amazon.com/Dorothy-Forster-Novel-Walter-Besant/dp/1241480478Dorothy Forster. a Novel. [Besant, Walter] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Dorothy Forster. a Novel. Feb 10, 2009 · Dorothy Forster: A Novel Paperback – February 10, 2009 by Walter Besant (Author) 4.2 out of 5 stars 2 ratings. See all formats and editions Hide other formats and editions. Price New from Used from Kindle "Please retry" $7.95 — — Hardcover "Please retry" $27.95 . … Reviews: 2Author: Walter BesantDorothy Forster (Volume 3); A Novel by Walter Besanthttps://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10404819...Told in the first person of Dorothy Forster, it is the story of the northern English Jacobites and the ill-fated rebellion of 1715, in which they attempted to restore James III …3.8/5Ratings: 4Reviews: 2Pages: 100Dorothy Foster by Walter Besant - Goodreadshttps://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10368482-dorothy-fosterIt was ever a distinction between the Forsters of. -

Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press This Page Intentionally Left Blank Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press

Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press This page intentionally left blank Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press Graham Law Waseda University Tokyo © Graham Law 2000 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2000 978-0-333-76019-2 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin’s Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). Outside North America ISBN 978-1-349-41360-7 ISBN 978-0-230-28674-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230286740 In North America ISBN 978-0-312-23574-1 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Arthur Morrison and the East End

Arthur Morrison and the East End This, the first critical biography of Arthur Morrison (1863–1945), presents his East End writing as the counter-myth to the cultural pro- duction of the East End in late-Victorian realism. Morrison’s works, par- ticularly Tales of Mean Streets (1894) and A Child of the Jago (1896), are often discussed as epitomes of slum fictions of the 1890s as well as prime examples of nineteenth-century realism, but their complex contempo- rary reception reveals the intricate paradoxes involved in representing the turn-of-the-century city. Arthur Morrison and the East End examines how an understand- ing of the East End in the Victorian cultural imagination operates in Morrison’s own writing. Engaging with the contemporary vogue for slum fiction, Morrison redressed accounts written by outsiders, positioning himself as uniquely knowledgeable about a place considered unknow- able. His work provides a vigorous challenge to the fictionalised East End created by his predecessors, while also paying homage to Charles Dickens, George Gissing, Walter Besant and Guy de Maupassant. Ex- amining the London sites which Morrison lived in and wrote about, this book is an excursion not into the Victorian East End, but into the fictions constructed around it. Eliza Cubitt received her BA and MA from King’s College London and was awarded a PhD from University College London (UCL) in 2016. She has published work on Morrison, W. Somerset Maugham and Mar garet Harkness. She has taught at UCL and at Universität Tübingen, Germany. Since 2014, she has been a committee member of the Literary London Society. -

The Revolt of Man Online

8IrpS [Free] The Revolt of Man Online [8IrpS.ebook] The Revolt of Man Pdf Free Walter Besant *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #14957456 in Books Walter Besant 2013-05-05Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .36 x 6.00l, .48 #File Name: 1484894391142 pagesThe Revolt of Man | File size: 53.Mb Walter Besant : The Revolt of Man before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Revolt of Man: 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. The story of `men' who live under the yolk of women in the futureBy John Drake"It is because the natural order has been reversed; the sex which should command and create is compelled to work in blind obedience."Thus is the story of `men' who live under the yolk of women in the future. This is an interesting book as it shows us a future where women rule, there is a new religion, the monarchy is abolished, and there are many good things. However, men, those pesky people want to rule. They want the old monarchy back (good god why?), and revolt against the ruling women.That's the story, and while I've told you the plot, it's the descriptions of life in this utopian or dystopian future world that make this book twice as good as the interesting plot. Written over 100 years ago, it's hard to believe, as its very much something that we could read today or see as a film and find much to discuss and think about.