Arthur Morrison and the East End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

Language and Conflict in English Literature from Gaskell to Tressell

ARTICULATING CLASS: LANGUAGE AND CONFLICT IN ENGLISH LITERATURE FROM GASKELL TO TRESSELL Timothy John James University of Cape Town Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN JANUARY 1992 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ABSTRACT ARTICULATING CLASS: LANGUAGE AND CONFLICT IN ENGLISH LITERATURE, FROM GASKELL TO TRESSELL Concentrating on English literary texts written between the 1830s and 1914 and which have the working class as their central focus, the thesis examines various ways in which class conflict inheres within the textual language, particularly as far as the representation of working-class speech is concerned. The study is made largely within V. N. Voloshinov's understanding of language. Chapter 1 examines the social role of "standard English" (including accent) and its relationship to forms of English stigmatised as inadequate, and argues that the phoneticisation of working-class speech in novels like those of William Pett Ridge is to indicate its inadequacy within a situation where use of the "standard language" is regarded as a mark of all kinds of superiority, and where the language of narrative prose has, essentially, the "accent" of "standard English". The periodisation of the thesis is discussed: the "industrial reformist" novels of the Chartist years and the "slum literature" of the 1880s and '90s were bourgeois responses to working-class struggle. -

THE IMAGINATION of CLASS Bivona Fm 3Rd.Qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page Ii Bivona Fm 3Rd.Qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page Iii

Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page i THE IMAGINATION OF CLASS Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page ii Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page iii THE IMAGINATION OF CLASS Masculinity and the Victorian Urban Poor Dan Bivona and Roger B. Henkle The Ohio State University Press Columbus Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bivona, Daniel. The imagination of class : masculinity and the Victorian urban poor / Dan Bivona, Roger B. Henkle. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-1019-8 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-9096-5 (cd-rom) 1. English prose literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Urban poor—Great Britain—History—19th century. 3. Social classes in literature. 4. Masculinity in lit- erature. 5. Sex role in literature. 6. Poverty in literature. 7. Poor in literature. I. Henkle, Roger B. II. Title. PR878.P66B58 2006 828’.80809352624—dc22 2005030683 Cover design by Dan O’Dair. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Printed by Thomson Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page v In Memory of Roger B. Henkle 1937–1991 Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page vi Bivona_fm_3rd.qxd 2/9/2006 4:56 PM Page vii - CONTENTS - Preface ix Foreword by -

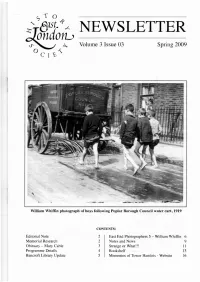

Onion ) Volume 3 Issue 03 Spring 2009

T 0 ast P NEWSLETTER onion_) Volume 3 Issue 03 Spring 2009 /C, C William Whiffin photograph of boys following Poplar Borough Council water cart, 1919 CONTENTS: Editorial Note 2 East End Photographers 5 — William Whiffin 6 Memorial Research 2 Notes and News 9 Obituary — Mary Cable 3 Strange or What!!! 11 Programme Details 4 Bookshelf 13 Bancroft Library Update 5 Mementos of Tower Hamlets - Website 16 ELVIS Newsletter Spring 2009 Editorial Note: MEMORIAL RESEARCH I At the Annual General Meeting, held on 30th October 2008, the following Committee Doreen and Diane Kendall, with Doreen members were re-elected: Philip Mernick, Osborne and other volunteers continue their Chairman, Doreen Kendall, Secretary, Harold work in the Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park Mernick, Membership, David Behr, meticulously researching graves and recording Programme, Ann Sansom, Doreen Osborne, memorial inscriptions. They would welcome and Rosemary Taylor. All queries regarding any help members can offer. Their work has membership should be addressed to Harold grown into a project of enormous proportions Mernick, 42 Campbell Road, Bow, London E3 and complexity, with an impressive database 4DT. of graves researched, with illustrations attached. Enquiries to Doreen Kendall, 20 Puteaux House, Cranbrook Estate, Bethnal Green, Unfortunately, due to pressure of work, London E2 ORF, Tel: 0208 981 7680, or Philip Doreen and Diane cannot undertake any Memick, email: philmernicks com research on behalf of individuals, but would welcome any information that has been Check out the History Society's website at uncovered through personal searches. Meet www.eastIondonhistory.org.uk. them in the Cemetery Park on the 2nd Sunday of every month at 2 pm, where you can Our grateful thanks go to all the contributors receive helpful advice and suggestions on the of this edition of the newsletter, with a special best way to conduct your searches. -

Arthur Morrison, the 'Jago', and the Realist

ARTHUR MORRISON, THE ‘JAGO’, AND THE REALIST REPRESENTATION OF PLACE Submitted in Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy UCL Department of English Language and Literature Eliza Cubitt 2015 ABSTRACT In vitriolic exchanges with the critic H.D. Traill, Arthur Morrison (1863-1945) argued that the term ‘realist’ was impossible to define and must be innately subjective. Traill asserted that Morrison’s A Child of the Jago (1896) was a failure of realism, conjuring a place that ‘never did and never could exist.’ And yet, by 1900, the East End slum fictionalised in Morrison’s novel had been supplanted by the realist mythology of his account: ‘Jago’ had become, and remains, an accepted term to describe the real historical slum, the Nichol. This thesis examines Morrison’s contribution to the late-Victorian realist representation of the urban place. It responds to recent renewed interest about realism in literary studies, and to revived debates surrounding marginal writers of urban literature. Opening with a biographical study, I investigate Morrison’s fraught but intimate lifelong relationship with the East End. Morrison’s unadorned prose represents the late-Victorian East End as a site of absolute ordinariness rather than absolute poverty. Eschewing the views of outsiders, Morrison re- placed the East End. Since the formation of The Arthur Morrison Society in 2007, Morrison has increasingly been the subject of critical examination. Studies have so frequently focused on evaluating the reality behind Morrison’s fiction that his significance to late-nineteenth century “New Realism” and the debates surrounding it has been overlooked. This thesis redresses this gap, and states that Morrison’s work signifies an artistic and temporal boundary of realism. -

Loughton and District Historical Society

LOUGHTON AND DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 197 MARCH–APRIL 2013 Price 40p, free to members www.loughtonhistoricalsociety.org.uk Golden Jubilee: 50th Season Grand Commuters and Forest for the People The Society has just published Grand Commuters: Buckhurst Hill and its Leading Families 1860–1940, by Lynn Haseldine Jones. Very little has been written about Buckhurst Hill for the best part of 50 years. From time to time, articles have appeared in this Newsletter and in local papers, but this is the first time the LDHS has been able to offer a book on any aspect of Buckhurst Hill’s history. Lynn Haseldine Jones has spent some years researching the families who effectively ran Buckhurst Hill. They were major employers in the town, they were influential in politics and religion locally, and their influence can be discerned even today. Many interesting families lived in the prosperous developing suburb of Buckhurst Hill in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. The golden age of the suburb began with the coming of the railway in 1856, which encouraged men of business to set up homes here for their often large families. Many were philanthropists, using their wealth and position to assist the community, either in politics or religion. The Buxtons and the Linders were politically Liberals; the Powells were supporters of the Conservative Party. The Powells, Buxtons and Howards were Anglicans; the Linders and the Westhorps were keen Congregationalists. Buckhurst Hill still benefits from their charity and evidence of their activities in the Church of St John the Baptist, Buckhurst Hill, and St James’s United Reformed (formerly the Congregational) Church can be seen to this day. -

'Flashes from the Slums': Aesthetics and Social Justice in Arthur Morrison

‘Flashes from the Slums’: Aesthetics and Social Justice in Arthur Morrison Audrey Murfin (Sam Houston State University, USA) The Literary London Journal, Volume 11 Number 1 (Spring 2014) Abstract: ‘“Flashes from the Slums”: Aesthetics and Social Justice in Arthur Morrison’ is a reappraisal of the late-Victorian slum writer Arthur Morrison. This article places Morrison in conversation with both Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1838) and with late 19th-century photography, most notably that of American Jacob Riis. Attention to the formal aspects of Morrison’s work, in particular the aesthetic influence of flash photography, reveals that Morrison’s politics are more progressive than has been seen to date. Keywords: Arthur Morrison, A Child of the Jago, flash photography, Jacob Riis, Oliver Twist The novels of late-Victorian slum novelist Arthur Morrison have been under- appreciated due in large part to critical assessments that his contempt for his characters is politically uncomfortable. Critics in Morrison’s own time felt that he was unsympathetic to his subjects. This misconception has persisted to the present day, with current critics reading his novels as embarrassing condemnations of the degenerate lower classes. This paper is largely an apology for Morrison, though I by no means want to suggest that Morrison’s politics were impeccable. Rather, attention to the formal aspects of his work reveals a deep desire to alleviate and ameliorate the conditions of the poorest in society, though at times obstructed by his own conflicts and despair. We can arrive at a more accurate reading of the intersection between Morrison’s artistic views and his politics through an examination of two predominant influences: The Literary London Journal, 11:1 (Spring 2014): 4 from the past, the socially progressive writings of Charles Dickens, and contemporaneously, the emerging technologies of urban photography. -

Detectives and Spies, 1880 - 1920

ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS, LAW AND SOCIAL SCIENCES OPERATING OUTSIDE THE LAW: DETECTIVES AND SPIES, 1880 - 1920. KATE MORRISON A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Anglia Ruskin University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Submitted: January 2017. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professor John Gardner for his invaluable intellectual advice, encouragement and support throughout the course of my research. His positive and informed engagement with a subject I found particularly stimulating gave me the confidence to pursue my research and expand the horizons of my study with new perspectives, giving me fresh ideas in the shaping of my research. I have benefitted from the assistance of Professor Rohan McWilliam, whose historical insights and vast knowledge of the literature within the field of crime fiction has been of immense value for which I am extremely grateful. I would also like to acknowledge my fellow research candidates, Steven White and Kirsty Harris who provided friendship and support in many ways along the journey to completion. i ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ARTS, LAW AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OPERATING OUTSIDE THE LAW: DETECTIVES AND SPIES, 1880 - 1920. KATE MORRISON January 2017. As a popular fiction hero Sherlock Holmes, embodies a mythical champion of enduring appeal, confirmed in his recent rebranding as defender of the oppressed for the twenty first century in a television series geared for the modern age. Stepping outside the boundaries of the law, he achieves an individualised form of justice superior to that of the judicial system in the eyes of his readers, yet, as I argue in this study, his long list of criminal offences places him firmly in the realms of criminality. -

Final Thesis Hunt.Pdf

UNDRESSING READERLY ANXIETIES: A STUDY OF CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES IN SHORT CRIME FICTION 1841-1911 by Alyson Hunt Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Chapter One: Whodunnit? Anxieties of Criminal Identification 31 Chapter Two: Anxieties of Sex and the Body 77 Chapter Three: Anxieties of the Imagination - Fashioning the 122 Fictional Female Detective Chapter Four: Anxieties of Fashionable Modernity in Fin de 177 Siècle Serialised Crime Fiction Chapter Five: Anxieties of Crime - Strands, Clues and Narrative Threads 221 Conclusion 265 Works Cited 275 Alyson Hunt 1 Abstract Dress changes the way that we, as readers, perceive and interpret characters within fiction because of the hugely subjective way that it influences individuals. We all have some experiences and opinions of dress because we have all been exposed to it in some way, whether consciously or unconsciously, and therefore the way that we read dress is fraught with ambiguity because our own experiences are so varied. Clothing functions as an indicator of gender, class, identity, aesthetic taste, fashion and social and economic success. It can sexualise and desexualise, entice and repel, reveal and conceal, lead and mislead and thus functions as a useful tool for writers to influence readers. Despite the instability of dress as a stable sign, writers make assumptions that readers understand what is being implied by dress and make conscious decisions to describe dress within their narratives. In crime fiction, clothing is particularly useful because it allows hiding in plain sight: as an item so mundane it is barely noticed by the reader, yet it can function as compelling clue to reveal the identity of a criminal. -

Arthur Morrison, Criminality, and Late-Victorian Maritime Subculture Diana Maltz

Arthur Morrison, Criminality, and Late-Victorian Maritime Subculture Diana Maltz I Introduction Modern critics commonly classify Arthur Morrison as an East End novelist. Following the vital scholarship of Peter J. Keating in the 1970s, they associate Morrison with other 1890s slum writers who employed unconventional spelling and punctuation to evoke Cockney speech: Henry Nevinson, Rudyard Kipling, W. Somerset Maugham, William Pett Ridge, Edwin Pugh, and Clarence Rook.1 For sure, Morrison was a native of Poplar, and lived much of his childhood in Grundy Street, just above the East India Dock Road. But the idiosyncratic identities of districts like the docks have been obscured by the repeated use by cultural historians of the generalizing phrase ‘East End’. In fact, as this essay explores, it was this close proximity to the wharves in particular that provided a key influence in Morrison’s other fictions. A way of addressing Morrison’s own interest in the specificity of locality is to examine his treatment of urban geography and consciousness of emerging methods of ethnography. Morrison prefaces his most well-known novel A Child of the Jago (1896) with a graphic map, and his frequent allusions to the ‘posties’ bounding the slum convey the district’s claustrophobic containment.2 As old Mr Beveridge tells the slum boy Dicky, one can only escape from the Jago by way of ‘gaol, the gallows, and the High Mob’ (pp. 51, 96). Dicky’s final revelation to Reverend Sturt that there is ‘’nother way out’ of the Jago points to his own ‘chiving’ [knifing] — and transcendent escape — at the hands of his arch-enemy Bobby Roper (p. -

The Great Hiatus and the Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (My Paper) Page 1 of 12

Notes on presentation for Nashville Scholars of Nashville The Great Hiatus and the Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (My Paper) Page 1 of 12 Meanwhile, During the Hiatus: Early Rivals of Sherlock Holmes By Drew R. Thomas What is the “Great Hiatus?” I want to make a few comments to put this discussion in context. Dorothy L. Sayers once wrote, “In 1887 A Study in Scarlet was flung like a bombshell into the field of detective fiction, to be followed within a few short and brilliant years by the marvelous series of Sherlock Holmes short stories. The effect was electric.” [Dorothy L. Sayers, The Omnibus of Crime (New York: Garden City Pub. Co., 1929), p.24.] Howard Haycraft, who wrote the first book-length history of the detective story (Murder for Pleasure), responded, “It may have been flung like a bombshell, but it didn’t explode.” [Howard Haycraft, Murder for Pleasure (), p. ] Doyle had trouble finding a publisher, and the one who finally bought it paid him £25—a paltry sum even in those days. And the rights never returned to Doyle tried unsuccessfully for the rest of his life to get the rights back. So that was it for Sherlock Holmes—or it would have been if an American editor from Lippincott’s magazine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—Joseph Marshall Stoddart— had not sailed across the Atlantic to bring together and encourage two young writers in whom he believed. Notes on presentation for Nashville Scholars of Nashville The Great Hiatus and the Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (My Paper) Page 2 of 12 Out of this encouragement, Doyle produced his second Holmes novel—The Sign of Four— (or The Sign of the Four, depending on which edition you have). -

Nation, Ethnicity, and the Geography of British Fiction, 1880-1940

Nation, Ethnicity, and the Geography of British Fiction, 1880-1940 Elizabeth F. Evans and Matthew Wilkens 07.13.18 Peer-Reviewed By: Stephen Ross Clusters: Race, Geography Article DOI: 10.22148/16.024 Dataverse DOI: 10.7910/10.7910/DVN/VW13KS Journal ISSN: 2371-4549 Cite: Elizabeth F. Evans and Matthew Wilkens, “Nation, Ethnicity, and the Geography of British Fiction, 1880-1940,” Cultural Analytics July 13, 2018. 10.22148/16.024 Among the most pressing problems in modernist literary studies are those re- lated to Britain’s engagement with the wider world under empire and to its own rapidly evolving urban spaces in the years before the Second World War.1 In both cases, the literary-geographic imagination—or unconscious—of the period between 1880 and 1940 can help to shed light on how texts by British and British- aligned writers of the era understood these issues and how they evolved over 1Special thanks to David Killingray, who assisted with research on foreign writers in Britain, and to Kara Mlynski, Patrick Evans, John Villaflor, Megan Kollitz, Dr. Melissa Dinsman, and Erik-John Fuhrer, who helped to prepare the corpora. Any errors are our own. The present work is an outcome of the Textual Geographies project, with funding support from the American Council of Learned Soci- eties, the National Endowment for the Humanities (#HK-250673-16 to Wilkens), and the University of Notre Dame. We gratefully acknowledge their assistance. Guangchen Ruan (Indiana University Data to Insight Center) assisted with large-scale named entity recognition over the full HathiTrust corpus, on which data this essay depends.