A Memoir of Patrick Fraser Tytler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grandmama of Europe: the Crowned Descendants of Queen Victoria Free Download

GRANDMAMA OF EUROPE: THE CROWNED DESCENDANTS OF QUEEN VICTORIA FREE DOWNLOAD Theo Aronson | 680 pages | 19 Nov 2014 | Thistle Publishing | 9781910198049 | English | United States Grandmama of Europe; the crowned descendants of Queen Victoria A very Grandmama of Europe: The Crowned Descendants of Queen Victoria book by Mr. Louise of Denmark. Paul of Greece [N Grandmama of Europe: The Crowned Descendants of Queen Victoria. A great starting off point as the book gives a very clear picture of those descendants of Queen Victoria who later became European monarchs. A woman of progressive opinions and… More. Seller Inventory Loved reading this piece of non-fic! About this Item: Theo Aronson, Sibylla of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. I must admit, it was difficult trying to keep track of all the whose who, and how they were all connected Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine. The author has used many many letters from Queen Victoria to her children and grandchildren and theirs to her, so there is a lot of pr I enjoyed this book greatly. All orders are dispatched the following working day from our UK warehouse. A re-release of a book originally published inthe coverage ends before the reigns of Juan Carlos of Spain or Carl Gustav of Sweden. Sophia Queen of the Hellenes. However, these two marriages were not the only unions amongst and between descendants of Victoria and Christian IX. Very thoroughly researched and includes many anecdotes. Tamara rated it it was amazing Jul 14, Great insight into the influence that Queen Victoria's progeny had over the world and how even those familial relationships couldn't stop the coming of WWI. -

The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate

Finlay, J. (2004) The early career of Thomas Craig, advocate. Edinburgh Law Review, 8 (3). pp. 298-328. ISSN 1364-9809 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/37849/ Deposited on: 02 April 2012 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk EdinLR Vol 8 pp 298-328 The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate John Finlay* Analysis of the clients of the advocate and jurist Thomas Craig of Riccarton in a formative period of his practice as an advocate can be valuable in demonstrating the dynamics of a career that was to be noteworthy not only in Scottish but in international terms. However, it raises the question of whether Craig’s undoubted reputation as a writer has led to a misleading assessment of his prominence as an advocate in the legal profession of his day. A. INTRODUCTION Thomas Craig (c 1538–1608) is best known to posterity as the author of Jus Feudale and as a commissioner appointed by James VI in 1604 to discuss the possi- bility of a union of laws between England and Scotland.1 Following from the latter enterprise, he was the author of De Hominio (published in 1695 as Scotland”s * Lecturer in Law, University of Glasgow. The research required to complete this article was made possible by an award under the research leave scheme of the Arts and Humanities Research Board and the author is very grateful for this support. He also wishes to thank Dr Sharon Adams, Mr John H Ballantyne, Dr Julian Goodare and Mr W D H Sellar for comments on drafts of this article, the anonymous reviewer for the Edinburgh Law Review, and also the members of the Scottish Legal History Group to whom an early version of this paper was presented in October 2003. -

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 A Century of Restorations Originally published as Das Jahrhundert der Restaurationen, 1814 bis 1906, Munich: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014. Translated by Volker Sellin An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-052177-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-052453-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-052209-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover Image: Louis-Philippe Crépin (1772–1851): Allégorie du retour des Bourbons le 24 avril 1814: Louis XVIII relevant la France de ses ruines. Musée national du Château de Versailles. bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Introduction 1 France1814 8 Poland 1815 26 Germany 1818 –1848 44 Spain 1834 63 Italy 1848 83 Russia 1906 102 Conclusion 122 Bibliography 126 Index 139 Introduction In 1989,the world commemorated the outbreak of the French Revolution two hundred years earlier.The event was celebratedasthe breakthrough of popular sovereignty and modernconstitutionalism. -

A Week at Waterloo

v ‘ 0 A W E E K A T I N 181 5 LADY DE LANCEY’S NAR R ATI VE BEING AN ACCO UNT O F HOW SHE NURSED HE R HUSBAND COLONEL S IR WI LLIAM OWE E , H D - LANCEY , Q UARTE R MASTE R GE NE RAL O F THE AR MY MORTALLY WOUN E IN THE R EAT , D D G BATTLE MAJOR B WAR D E DITE D BY . R R O Y AL EN G INE E R S LONDO N JO HN MUR R AY , ALBE MARLE STR E E T 1906 “ D im i s t he ru m u r o f a c mm n fi ht o o o g , When h st meet s h st and man names are su nk o o , y ; ” Bu t o f a s i n le c mb at Fame s ak s c ear g o pe l . —Sokrab a nd R ustum . LIST O F ILLUSTR AT IO N S 5 f MAJO R WILLIAM HOW D A Y 4 th R . O E E L NCE , egt F 00 F rom a miniature in the ossessio n 0. 18 . oot, p Wm Hea thco te D e Lance o New Y k F r nt s of . y f or o i piece THE O LD OSS O I R WM Y r c i v G C S . D A R F E L NCE , e e ed af r rvi n i n th e in la r Wa r i te se g Pen su , w th a fo r Ta av ra i v a am a n a San cl sps l e , N e, S l c , d Vi i I n th s ssi n a ian an r a . -

History of the German Struggle for Liberty

MAN STRUG "i L UN SAN DIE6O CHARLES S. LANDERS, NEW BRITAIN, CONN. DATE, .203 HOW THE ALLIED TROOPS MARCHED INTO PARIS HISTORY OF THE GERMAN STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY BY POULTNEY BIGELOW, B.A. ILLUSTRATED WITH DRAWINGS By R. CATON WOODVILLE AND WITH PORTRAITS AND MAPS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. II. NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS 1896 Copyright, 189G, by HARPER & BROTHERS. All rigJiU rtltntd. CONTENTS OF VOL. II CUAPTEtt PAGB I. FREDERICK WILLIAM DESPAIRS OP nis COUNTRY 1811. 1 II. NAPOLEON ON THE EVE OF Moscow 9 III. THE FRENCH ARMY CONQUERS A WILDERNESS ... 18 IV. NAPOLEON TAKES REFUGE IN PRUSSIA 30 V. GENERAL YORCK, THE GLORIOUS TRAITOR 39 VI. THE PRUSSIAN CONGRESS OF ROYAL REBELS .... 50 VII. THE PRUSSIAN KING CALLS FOR VOLUNTEERS . C2 VIII. A PROFESSOR DECLARES WAR AGAINST NAPOLEON. 69 IX. THE ALTAR OF GERMAN LIBERTY 1813 ..... 80 X. THE GERMAN SOLDIER SINGS OF LIBERTY 87 XI. THE GERMAN FREE CORPS OF LUTZOW 95 XII. How THE PRUSSIAN KING WAS FINALLY FORCED TO DECLARE WAR AGAINST NAPOLEON 110 XIII. PRUSSIA'S FORLORN HOPE IN 1813 THE LANDSTURM . 117 XIV. LUTZEN '.'........"... 130 XV. SOME UNEXPECTED FIGHTS IN THE PEOPLE'S WAR. 140 XVI. NAPOLEON WINS ANOTHER BATTLE, BUT LOSES HIS TEMPER 157 XVII. BLUCHER CUTS A FRENCH ARMY TO PIECES AT THE KATZBACII 168 XVIII. THE PRUSSIANS WIN BACK WHAT THE AUSTRIANS HAD LOST 176 XIX. THE FRENCH TRY TO TAKE BERLIN, BUT ARE PUT TO ROUT BY A GENERAL WHO DISOBEYS ORDERS . 183 XX. How THE BATTLE OF LEIPZIG COMMENCED . 192 v CONTENTS OF VOL. II CHAPTER VAGB XXI. -

Why NATO Endures

This page intentionally left blank Why NATO Endures Why NATO Endures develops two themes as it examines military alli- ances and their role in international relations. The first is that the Atlantic Alliance, also known as NATO, has become something very different from virtually all pre-1939 alliances and many contemporary alliances. The members of early alliances frequently feared their allies as much if not more than their enemies, viewing them as temporary accomplices and future rivals. In contrast, NATO members are almost all democracies that encourage each other to grow stronger. The book’s second theme is that NATO, as an alliance of democracies, has developed hidden strengths that have allowed it to endure for roughly sixty years, unlike most other alliances, which often broke apart within a few years. Democracies can and do disagree with one another, but they do not fear one another. They also need the approval of other democracies as they conduct their foreign policies. These traits constitute built-in, self-healing tendencies, which is why NATO endures. Wallace J. Thies, a Yale Ph.D., has held full-time teaching positions in political science at the University of Connecticut (Storrs), the University of California, Berkeley, and the Catholic University of America. Why NATO Endures is his third book. His two previous books are When Governments Collide: Coercion and Diplomacy in the Vietnam Conflict (1980) and Friendly Rivals: Bargaining and Burden-Shifting in NATO (2003). He has also published articles in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Strategic Studies, International Interactions, Comparative Strategy, and European Security and has served as an International Affairs Fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations, working at the U.S. -

Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill

Marc Fehlmann A Building from which Derived "All that is Good": Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2005) Citation: Marc Fehlmann, “A Building from which Derived ‘All that is Good’: Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2005), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn05/207-a- building-from-which-derived-qall-that-is-goodq-observations-on-the-intended-reconstruction- of-the-parthenon-on-calton-hill. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2005 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Fehlmann: A Building from which Derived "All that is Good" Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 3 (Autumn 2005) A Building from which Derived "All that is Good": Observations on the Intended Reconstruction of the Parthenon on Calton Hill by Marc Fehlmann When, in 1971, the late Sir Nikolaus Pevsner mentioned the uncompleted National Monument at Edinburgh in his seminal work A History of Building Types, he noticed that it had "acquired a power to move which in its complete state it could not have had."[1] In spite of this "moving" quality, this building has as yet not garnered much attention within a wider scholarly debate. Designed by Charles Robert Cockerell in the 1820's on the summit of Calton Hill to house the mortal remains of those who had fallen in the Napoleonic Wars, it ended as an odd ruin with only part of the stylobate, twelve columns and their architrave at the West end completed in its Craigleith stone (fig. -

Johnston of Warriston

F a m o u s Sc o t s S e r i e s Th e following Volum es are now ready M S ARLYLE H ECT O R . M C HERSO . T HO A C . By C A P N LL N R M Y O L H T SM E T O . A A A SA . By IP AN A N H U GH MI R E T H LE SK . LLE . By W. K I A H K ! T LOR INN Es. JO N NO . By A . AY R ERT U RNS G BR EL SET OUN. OB B . By A I L D O H GE E. T H E BA L A I ST S. By J N DDI RD MER N Pro fe sso H ER KLESS. RICH A CA O . By r SIR MES Y SI MPSON . EV E L T R E S M SO . JA . By B AN Y I P N M R P o fesso . G R E BLA I KIE. T HOMAS CH AL E S. By r r W A D N MES S ELL . E T H LE SK. JA BO W . By W K I A I M L E OL H T SME T O . T OB AS S O L T T . By IP AN A N U G . T O MON D . FLET CHER O F SA LT O N . By . W . R U P Sir GEOR E DO L S. T HE BLACKWOOD G O . By G UG A RM M LEOD OH ELL OO . -

James Hutton's Reputation Among Geologists in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

The Geological Society of America Memoir 216 Revising the Revisions: James Hutton’s Reputation among Geologists in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries A. M. Celâl Şengör* İTÜ Avrasya Yerbilimleri Enstitüsü ve Maden Fakültesi, Jeoloji Bölümü, Ayazağa 34469 İstanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT A recent fad in the historiography of geology is to consider the Scottish polymath James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth the last of the “theories of the earth” genre of publications that had begun developing in the seventeenth century and to regard it as something behind the times already in the late eighteenth century and which was subsequently remembered only because some later geologists, particularly Hutton’s countryman Sir Archibald Geikie, found it convenient to represent it as a precursor of the prevailing opinions of the day. By contrast, the available documentation, pub- lished and unpublished, shows that Hutton’s theory was considered as something completely new by his contemporaries, very different from anything that preceded it, whether they agreed with him or not, and that it was widely discussed both in his own country and abroad—from St. Petersburg through Europe to New York. By the end of the third decade in the nineteenth century, many very respectable geologists began seeing in him “the father of modern geology” even before Sir Archibald was born (in 1835). Before long, even popular books on geology and general encyclopedias began spreading the same conviction. A review of the geological literature of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries shows that Hutton was not only remembered, but his ideas were in fact considered part of the current science and discussed accord- ingly. -

'Some Few Miles from Edinburgh': Commemorating the Scenes of the Gentle Shepherd in Ramsay Country

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 46 Issue 2 Allan Ramsay's Future Article 5 12-18-2020 'Some Few Miles from Edinburgh': Commemorating the Scenes of The Gentle Shepherd in Ramsay Country Craig Lamont University of Glasgow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Lamont, Craig () "'Some Few Miles from Edinburgh': Commemorating the Scenes of The Gentle Shepherd in Ramsay Country," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 46: Iss. 2, 40–60. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol46/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SOME FEW MILES FROM EDINBURGH”: COMMEMORATING THE SCENES OF THE GENTLE SHEPHERD IN RAMSAY COUNTRY Craig Lamont In Edinburgh, Allan Ramsay is remembered with several markers in tangible locations, for example with the portrait monument in West Princes Street Gardens (1865) and among the many other writers on the Scott Monument (1844/6).1 Outside Edinburgh, the situation is not so concrete, and the mode of commemoration differs.2 Where the Edinburgh monuments portray Ramsay himself, commemorations in the countryside were based instead on his chief dramatic work The Gentle Shepherd; A Scots Pastoral Comedy (Edinburgh: Mr. Tho. Ruddiman for the author, 1725), and a culture of commemoration -

Founding Fellows

Founding Members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Alexander Abercromby, Lord Abercromby William Alexander John Amyatt James Anderson John Anderson Thomas Anderson Archibald Arthur William Macleod Bannatyne, formerly Macleod, Lord Bannatyne William Barron (or Baron) James Beattie Giovanni Battista Beccaria Benjamin Bell of Hunthill Joseph Black Hugh Blair James Hunter Blair (until 1777, Hunter), Robert Blair, Lord Avontoun Gilbert Blane of Blanefield Auguste Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy Ebenezer Brownrigg John Bruce of Grangehill and Falkland Robert Bruce of Kennet, Lord Kennet Patrick Brydone James Byres of Tonley George Campbell John Fletcher- Campbell (until 1779 Fletcher) John Campbell of Stonefield, Lord Stonefield Ilay Campbell, Lord Succoth Petrus Camper Giovanni Battista Carburi Alexander Carlyle John Chalmers William Chalmers John Clerk of Eldin John Clerk of Pennycuik John Cook of Newburn Patrick Copland William Craig, Lord Craig Lorentz Florenz Frederick Von Crell Andrew Crosbie of Holm Henry Cullen William Cullen Robert Cullen, Lord Cullen Alexander Cumming Patrick Cumming (Cumin) John Dalrymple of Cousland and Cranstoun, or Dalrymple Hamilton MacGill Andrew Dalzel (Dalziel) John Davidson of Stewartfield and Haltree Alexander Dick of Prestonfield Alexander Donaldson James Dunbar Andrew Duncan Robert Dundas of Arniston Robert Dundas, Lord Arniston Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville James Edgar James Edmonstone of Newton David Erskine Adam Ferguson James Ferguson of Pitfour Adam Fergusson of Kilkerran George Fergusson, Lord Hermand -

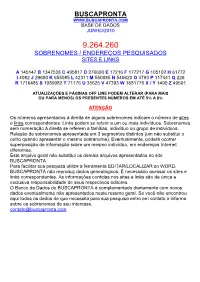

Buscapronta Base De Dados Junho/2010

BUSCAPRONTA WWW.BUSCAPRONTA.COM BASE DE DADOS JUNHO/2010 9.264.260 SOBRENOMES / ENDEREÇOS PESQUISADOS SITES E LINKS A 145147 B 1347538 C 495817 D 276690 E 17216 F 177217 G 105102 H 61772 I 4082 J 29600 K 655085 L 42311 M 550085 N 540620 O 4793 P 117441 Q 226 R 1716485 S 1089982 T 71176 U 35625 V 47393 W 1681776 X / Y 1490 Z 49591 ATUALIZAÇÕES E PÁGINAS OFF LINE PODEM ALTERAR (PARA MAIS OU PARA MENOS) OS PRESENTES NÚMEROS EM ATÉ 5% A 8% ATENÇÃO Os números apresentados à direita de alguns sobrenomes indicam o número de sites e links correspondentes. Links podem se referir a um ou mais indivíduos. Sobrenomes sem numeração à direita se referem a famílias, indivíduo ou grupo de indivíduos. Relação de sobrenomes apresentada em 3 segmentos distintos (um não substitui o outro quando apresentar o mesmo sobrenome). Eventualmente, poderá ocorrer superposição de informação sobre um mesmo indivíduo, em endereços Internet diferentes. Este arquivo geral não substitui os demais arquivos apresentados no site BUSCAPRONTA. Para facilitar sua pesquisa utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR so WORD. BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos. È necessário acessar os sites e links correspondentes. As informações contidas nos sites e links são de única e exclusiva responsabilidade de seus respectivos editores. O Banco de Dados do BUSCAPRONTA é complementado diariamente com novos dados eventualmente não apresentados neste resumo geral. Se você não encontrou aqui todos os dados de que necessita para sua pesquisa entre em contato e informe sobre os sobrenomes