Nuclear Deterrent Cooperation Involving Britain, France, and Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desiring Myth: History, Mythos and Art in the Work of Flaubert and Proust

Desiring Myth: History, Mythos and Art in the Work of Flaubert and Proust By Rachel Anne Luckman A thesis submitted for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of French Studies College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham August 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Previous comparative and parallel ‘genetic criticisms’ of Flaubert and Proust have ignored the different historical underpinnings that circumscribe the act of writing. This work examines the logos of Flaubert and Proust’s work. I examine the historical specificity of A la recherche du temps perdu, in respect of the gender inflections and class-struggles of the Third French Republic. I also put forward a poetics of Flaubertian history relative to L’Education sentimentale. His historical sense and changes in historiographic methodologies all obliged Flaubert to think history differently. Flaubert problematises both history and psychology, as his characterisations repeatedly show an interrupted duality. This characterization is explicated using René Girard’s theories of psychology, action theory and mediation. Metonymic substitution perpetually prevents the satisfaction of desire and turns life into a series of failures. -

2013-2014 Newsletter

WILLIAMS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF ART OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ART INSTITUTE WILLIAMS GRAD ART THE CLARK 2013–2014 NEWSLETTER LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Marc Gotlieb Dear Alumni, Art Department in the field of African Art, and who will be teaching in the graduate program this spring. Greetings from Williamstown. I hope you enjoy our redesigned alumni newsletter, the last and The newsletter includes a special conversation with most significant phase of a visual identity project Michael Ann Holly, Starr Director of Research that includes the launch of a new website and Emeritus at the Clark, and this year’s Robert other communications pieces designed to capture Sterling Clark Visiting Professor. Many thanks to some of the freshness and contemporaneity of the program and its Ashley Lazevnick MA ’12 and Oliver Wunsch setting. By now many of you have had the opportunity to visit the MA ’11 for taking this on! And many thanks, too, new Clark and its spectacular new wing, including renovated galleries to our post-doctoral fellow, Kristen Oehlrich, for and a reflecting pool looking out over Stone Hill. But there is more to putting this splendid newsletter together. Most of come—the Manton Building, which houses the Graduate Program and all, thanks to our alumni for contributing updates the library, will reopen to the public this summer, with a new spacious to the newsletter! reading room, a new works on paper study center and gallery, and facil- With all best wishes, ities that will bring the entire complex fresh new life. If you do visit, please stop by and say hello—Karen, George, Kristen and I would be Marc delighted to see you. -

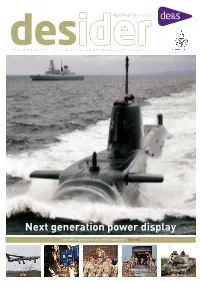

Next Generation Power Display

Apr/May 10 Issue 24 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Next generation power display Latest DE&S organisation chart and PACE supplement See inside Parc Chain Dress for Welcome Keeping life gang success home on track Picture: BAE Systems NEWS 5 4 Keeping on track Armoured vehicles in Afghanistan will be kept on track after DE&S extended the contract to provide metal tracks the vehicles run on. 8 UK Apache proves its worth The UK Apache attack helicopter fleet has reached the landmark of 20,000 flying hours in support of Operation Herrick 8 Just what the doctor ordered! DE&S’ Chief Operating Officer has visited the 2010 y Nimrod MRA4 programme at Woodford and has A given the aircraft the thumbs up after a flight. /M 13 Triumph makes T-boat history The final refit and refuel on a Trafalgar class nuclear submarine has been completed in Devonport, a pril four-year programme of work costing £300 million. A 17 Transport will make UK forces agile New equipment trailers are ready for tank transporter units on the front line to enable tracked vehicles to cope better with difficult terrain. 20 Enhancement to a soldier’s ‘black bag’ Troops in Afghanistan will receive a boost to their personal kit this spring with the introduction of cover image innovative quick-drying towels and head torches. 22 New system is now operational Astute and Dauntless, two of the most advanced naval A new command system which is central to the ship’s fighting capability against all kinds of threats vessels in the world, are pictured together for the first time is now operational on a Royal Navy Type 23 frigate. -

Devonport Naval Base's Nuclear Role

Devonport naval base’s CND nuclear role Her Majesty’s Naval Base Devonport, in the middle of the city of Plymouth, is where the United Kingdom’s submarines – including those armed with Trident missiles and nuclear warheads – undergo refuelling of their nuclear reactors and refurbishment of their systems. This work has potentially hazardous consequences, and the nuclear site has a history of significant accidents involving radioactive discharges. LL of Britain’s submarines are nuclear- both there and in Devonport. Submarines will be powered and the four Vanguard-class defueled before the dismantling process begins. Asubmarines carry the UK’s nuclear weapons Defueling is the most dangerous operation of the system, Trident. One dock at Devonport is entire decommissioning process. specifically designed to maintain these nuclear weapons submarines. Other docks are used to store Radioactive Reactor Pressure Vessels (each the size nuclear submarines that have been decommissioned of two double-decker buses and weighing around and await having their nuclear reactors removed and 750 tonnes) will be removed from the nuclear- the radioactive metals and components dismantled powered submarines at both Devonport and and sent as nuclear waste for storage. Rosyth dockyards and stored intact at Capenhurst, prior to disposal in a planned – but as yet non- In 2013 the Ministry of Defence confirmed that existent – Geological Disposal Facility. The Devonport is one of two sites in the UK (the other Ministry of Defence (MoD) is yet to find a location is Rosyth in Fife) where decommissioned nuclear- for storing intermediate level radioactive waste, and powered submarines will be dismantled once a site is using storage facilities at Sellafield reprocessing for the waste has been identified. -

Ministry of Defence the United Kingdom's Future Nuclear Deterrent

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The United Kingdom’s Future Nuclear Deterrent Capability REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL | HC 1115 Session 2007-2008 | 5 November 2008 The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending on behalf of Parliament. The Comptroller and Auditor General, Tim Burr, is an Officer of the House of Commons. He is the head of the National Audit Office which employs some 850 staff. He and the National Audit Office are totally independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of all Government departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to report to Parliament on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies have used their resources. Our work saves the taxpayer millions of pounds every year: at least £9 for every £1 spent running the Office. MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The United Kingdom’s Future Nuclear Deterrent Capability Ordered by the LONDON: The Stationery Office House of Commons £14.35 to be printed on 3 November 2008 REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL | HC 1115 Session 2007-2008 | 5 November 2008 This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act. Tim Burr Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 28 October 2008 The National Audit Office study team consisted of: Tom McDonald, Gareth Tuck, Helen Mullinger and James Fraser, under the direction of Tim Banfield This report can be found on the National Audit -

Lessons from the United Kingdom's Astute

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. JOHN F. SCHANK • FRANK W. LACROIX • ROBERT E. MURPHY • CESSE IP MARK V. ARENA • GORDON T. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 620 23 January 2017 No. 96 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 23 January 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON.THERESA MAY, MP, JULY 2016) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Sir Michael Fallon, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Justine Greening, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. David Davis, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH—The Rt Hon. Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Damian Green, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT—The Rt Hon. Chris Grayling, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT—The Rt Hon. -

Martin Hopkinson

M a r t i n H o p k i n s o n address: 29 Keats Close, Winchester, S022 4HR telephone: 01962 864 249 e-mail: [email protected] Professional profile A successful project and risk management professional with in-depth experience gained from working with a wide range of organisations in both defence and non-defence industries. Has made major contributions to both the projects in which he has worked and to the development of their owning organisation’s project management processes. Objective To deliver exceptional value to clients with major projects as Director and lead consultant for Risk Management Capability ltd. Key technical skills Project Management Risk Management Risk Tools Risk management Qualitative techniques Active Risk Manager Project planning Schedule risk analysis Predict 4. Earned Value management Cost risk analysis Pertmaster Project sponsorship NPV risk analysis @RISK for Excel Project governance Decision analysis Risk Maturity Model Career summary 1999–2011 HVR Consulting Services and QinetiQ (after its acquisition of HVR) Won the Project Risk Maturity Model (RMM) contract first placed by the Defence Procurement Agency (DPA) in 2002 and continued until the formation of Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) in 2008. This contract resulted in the RMM being used to assess projects with a combined value exceeding £60 billion and enabled the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) to gain appropriate assurance in its risk-based project forecasts used for Main Gate approval. Developed the guidance, risk tool and reporting formats for QinetiQ’s project risk management process rolled out as part of the company’s Fit for Growth programme. -

The Myth of Holy Grail in Dan Brown's the Da Vinci Code

THE MYTH OF HOLY GRAIL IN DAN BROWN’S THE DA VINCI CODE THESIS By: MUHAMMAD FATIH AL AZIZ 10320066 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LETTER DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALANG 2015 i THE MYTH OF HOLY GRAIL IN DAN BROWN’S THE DA VINCI CODE THESIS Presented to Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University of Malang Advisor: Mundi Rahayu, M.Hum By: Muhammad Fatih Al Aziz 10320066 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LETTER DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALANG 2015 ii APPROVAL SHEET This is to certify that Muhammad Fatih Al Aziz’s thesis entitled The Myth of Holy Grail in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code has been approved by the thesis advisor for further approval by the Board of Examiners. Malang, June 23, 2015 Approved by Acknowledged by The Advisor, The Head of the Department of English Language and Literature, Mundi Rahayu, M.Hum Dr.Syamsudin, M.Hum NIP. 196802262006042001 NIP. 196911222006041001 The Dean of Faculty of Humanities and Culture Dr.Hj. Isti'adah, M.A NIP. 19670313 199203 2 002 iii LEGITIMATION SHEET This is to certify that Muhammad Fatih Al Aziz’s thesis entitled “The Myth of Holy Grail in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code” has been approved by the Board of Examiners as the requirement for the degree of Sarjana in Humanity. The Board of Examiners Signatures Muzakki Afifuddin, M.Pd NIP. 197610112011011005 Dr. Syamsudin, M.Hum NIP. 196911222006041001 Mundi Rahayu, M.Hum NIP. 196802262006042001 Approved by The Dean of the Faculty of Humanities Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University, Malang Dr.Hj. -

![[No.]: [Chapter Title]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2488/no-chapter-title-2732488.webp)

[No.]: [Chapter Title]

2 Europe United Kingdom Plymouth 2.1 The delegation visited the Babcock/Royal Naval Dockyard Devonport 2.2 Babcock explained to the delegation that their role was very much as a service provider, not a traditional Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM). This meant that Babcock had long term contracts with a very small number of customers. It was a successful model, noting that Babcock was now the major supplier to the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). 2.3 Babcock explained their role in surface ships construction and support, and provided background to the consolidation process that had been taking place in UK dockyards. This is part of a UK Government policy to create an indigenous support capability. 2.4 The Babcock presentation explained the split between BAE Systems and Babcock in construction and support, with BAE Systems being the builder of submarines and Babcock the support contractor. It was noted this distinction is less clear cut for surface ships, with Babcock involved in some construction work and BAE Systems involved in some support work. 2.5 The delegation was interested in how this ‘single source’ approach, worked for the UK. Rear Admiral Lloyd stated that the UK has no other option – there is no alternative capability available and the UKMOD knows it has to deal with this situation. Babcock and BAE Systems are seen an integral parts of the ‘strategic enterprise’ of shipbuilding and 10 support. This is in part driven by the overheads of establishing and maintaining the required technical expertise. 2.6 Babcock explained to the delegation that, given the life-cycle from start of first boat to the disposal of the last, submarines required a fifty year program plan. -

DEF 40366 FSISP INT AW.Indd

A PLAN FOR THE NAVAL SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY FUTURE SUBMARINE INDUSTRY SKILLS PLAN FUTURE SUBMARINE INDUSTRY SKILLS PLAN ___ A PLAN FOR THE NAVAL SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY www.defence.gov.au/dmo/publications/fsisp.cfm Acknowledgement The CEO DMO would like to acknowledge the major contributions from the study team of Mr Andrew Cawley, Mr Mel Melnyczek, Mr Paul Curtis and the contributions of Rear Admiral Oscar Hughes (ret’d) and Rear Admiral Rowan Moffi tt. In addition CEO would like to acknowledge peer review comments provided by senior personnel within Defence and industry. © 2013 Commonwealth of Australia This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, which is available through the Department of Defence. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director of DMO Media and Executive Communications Defence Materiel Organisation Russell Offi ces, R2-5-B036 Canberra ACT 2600 — The following organisations have provided images and graphics for use in this publication: Austal Australian Marine Complex AWD Alliance ASC BAE Systems Australia Defence SA General Dynamics Electric Boat Forgacs Engineering Raytheon Australia SAAB Systems Australia Thales Australia FUTURE SUBMARINE INDUSTRY SKILLS PLAN ___ A PLAN FOR THE NAVAL SHIPBUILDING INDUSTRY CONTENTS FOREWORD> IV MR WARREN kING & MR ANDREW CAWLEY> IV MR DAVID MORTIMER AO VI INTRODUCTION> VIII EXECUTIVE>SUMMARY> X SECTIONS 01 -

David Garrioch, Religious Identities and the Meaning of Things In

Religious Identities in Eighteenth-Century Paris 17 Religious Identities and the Meaning of Things in Eighteenth-Century Paris David Garrioch On January 6, 1777, Manon Phlippon had an adventure. She was twenty-three, the daughter of a respectable engraver and is better known to most people by her later married name of Madame Roland. It was the fête des rois, she was at home alone and she did something she would not normally have done. Donning her servant’s clothes—a short skirt and ragged top with a large red apron and a coarse cotton cloak—she went out to discover the city. As she pushed her way through the crowds, unchaperoned and unrecognized, she experienced a new sense of freedom, “jostled by people who would have made way for me if they had seen me in my finery.”1 Her observation, recorded in a letter to a friend, is a reminder that what Daniel Roche has called the “hierarchy of appearances” was still important in late eighteenth-century Paris. Rank was marked by dress and people reacted accordingly. Largely thanks to Roche’s work, clothing is the best-known aspect of Paris material culture in this period, but it was only one of the markers of social identity. People also indicated who they were through their choice of furniture and of other objects with which they surrounded themselves. Scientific accessories like thermometers, barometers and maps pointed to a modern man of science, a devotee of the Enlightenment, while musical instruments were an accessory for a lady of quality.2 Both were markers of status and of gender.