Pride of Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

OUTIS the NEWIN Memphis Pride Fest Powered by a 3-DAY GRAND CELEBRATION!

OUTIS THE NEWIN Memphis Pride fest Powered by A 3-DAY GRAND CELEBRATION! FRIDAY, SEPT 23 Saturday, SEPT 24 Sunday, SEPT 25 The Pride Concert Pride Festival Pride Brunch crawl 7p q Handy Park 10a - 5p q Robert Church Park Starts at 1 - 4p in Cooper Young Page 6 Page 12 Page 3 Pride Parade 1 - 2p q Beale Street Page 13 PROUD SPONSOR OF THE LGBT PRIDE PARADE MGM Resorts named one of the “Best Places to Work for LGBT Equality” #GoldStrikeMGM © 2016 MGM Resorts International®. Gambling Problem? Call 1.888.777.9696 Table of contents 4 ........................Welcome to the 13th Annual 15 ..................Performing Artists Memphis Pride Fest The Zoo Girls Midtown Queers 6 ........................Pride Concert Lisa Michaels 7 ........................2016 Grand Marshals 16 ..................Festival Vendors 8 ........................Meet the Board 17 ..................Drum Circle Project 10 ..................2016 Mister & Miss Mid-South Pride OUTMacc Onner IS THE18 ..................Q&A Aubrey Ombre NEW Queer Youth from Playhouse ..................Performing Artists 12 ..................Festival Layout 18 Melanie P. & Mixx Talent ..................Parade Route 13 Mike Hewlett & the Racket 14 ..................Meet Your 2016 Event Hosts ..................After Parties Jaiden Diore Fierce 19 Fannie Mae 20 .................2016IN Sponsors Welcome to the 13th Annual Memphis Pride Fest From your President, Sept 23rd at 7:00pm, followed by the Festival and Parade on I want to welcome you to your 13th Annual Memphis Pride Fest Saturday Sept 24th from 10:00am to 5:00pm with the parade at and Parade with this year’s theme as “OUT is the New IN.” This 1:00pm going down the historic Beale Street, finally we end the year has been an amazing year of growth and expansion for fun-filled weekend with a brunch crawl through Cooper Young The Mid-South Pride Organization. -

RAINBOW READY Resources for Communicating LGBT+ Inclusion in Sport Strategy and Media Guidelines Introduction Index

RAINBOW READY Resources for Communicating LGBT+ Inclusion in Sport Strategy and media guidelines Introduction Index Jon Holmes, Founder and Network Lead, Sports Media LGBT+ 4 Questions and Answers About Sports Media LGBT+, and the background to these resources Every day, conversations about sport are playing out - face-to-face, at a local level, and on national and international platforms with power and influence. 6 Listening and Learning In the media, it’s not just press officers, journalists and PR Advice on how to prepare effectively before publishing comms or editorial professionals who are leading this discourse. Fans, agents and administrators, as well as athletes and coaches themselves, are among those frequently 8 Getting The Message Right communicating in the public space. Working within limitations; themes and topics; LGBT+ media guidelines Conversations about LGBT+ inclusion in sport often present challenges, but the importance of addressing the topic continues to grow. Highlighting inclusion initiatives is a way to attract new audiences, while providing space for LGBT+ people and allies to tell their stories can have significant impact, inviting empathy and understanding. 10 Potential Pitfalls Mis-steps can weaken the impact of your message - here are some to avoid Sports Media LGBT+ is a network, advocacy and consultancy group. By amplifying LGBT+ voices in the media, championing authenticity, and sharing examples of good practice, we’re working to assist our industry 11 Handling Reactions and other sectors on communicating inclusion with the Amid the positive responses, there may be negativity - here’s what to expect goal of making sport more welcoming for all. -

LGBTQ+ Support March 2020

LGBTQ+ Sources of support for LGBTQ+ people This directory is a work in progress and will be updated regularly. I have collated it in response to staff requests to know more about the support available for LGBTQ+ people. If you know of groups, places or events that could promote good mental health and wellbeing in the local LGBTQ+ community, please email me at: [email protected] Thank-you Michelle Savage, LGBTQ+ Project Manager, March 2020 Disclaimer: Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information provided in this directory, we do not accept any responsibility or liability for any errors that have occurred. We offer an impartial service and we cannot recommend or endorse any providers listed. We suggest that you contact each local group directly to find out more. This information does not represent a recommendation or an endorsement of a service or provider. Page !1 NATIONAL HELPLINES Switchboard LGBT+ Helpline Tel: 0300 330 0630 (Open 10:00-22:00 every day) Web: www.switchboard.lgbt/help/ Provides an information, support and referral service for lesbians, gay men and bisexu- al and trans people – and anyone considering issues around their sexuality and/or gen- der identity. Mermaids Helpline Tel: 0808 801 0400 (Monday – Friday; 9am – 9pm) Web: www.mermaidsuk.org.uk/contact-us/ Mermaids provides a helpline aimed at supporting transgender youth up to and includ- ing the age of 19, their families and professionals working with them. Mindline Trans+ Helpline Tel: 0300 330 5468 (Mondays and Fridays from 8pm to midnight) Web: www.bristolmind.org.uk/help-and-counselling/mindline-transplus/ A national helpline, you can call from anywhere in the UK. -

Equalities-And-Cohesion-Policy-Sept

EQULITIES AND COHESION POLICY Date of publication: Sept 2017 Review date: Oct 2018 Signed ……………………………. Chairman of Governors Date ………………………… 1. School Mission Statement / Principles Our Vision and Values: Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School aims to achieve excellence in all its fields of endeavour by creating an inspired, ambitious, confident and caring community of young people and adults. The school aspires to deliver an exceptional quality of teaching and learning.~ It promotes high expectations for both staff and students and encourages maximum effort, intellectual curiosity and independence of mind. By fostering a distinctive Borlase spirit with a strong ethos of consideration, the whole school community works together to create accomplished and well-rounded young people. The school actively supports and encourages each individual student to develop his/her talents and realise his/her fullest potential in both academic and non-academic fields. The school aims to provide the quality of education to enable students to achieve their preferred next steps in higher education or employment. The school embraces, accepts, and promotes tolerance of individual differences and treating everyone with equal respect across the school and wider community. What is Equality? Equality is the principle of equal treatment for all people irrespective of their gender, ethnicity, disability, religious belief, sexual orientation, age, or any other recognised area of discrimination. What is diversity? Diversity is the acceptance that we are all different but we are all equal. Diversity focuses on valuing and celebrating the strengths in people’s differences. What is community cohesion? Community cohesion is to have common vision and civic pride, valued and celebrated diversity, clear rights and responsibilities, equal life chances for all and strong relations between different communities. -

Intersectionality: Race/Ethnicity and LGBTQ People in Brighton & Hove

Intersectionality: Race/Ethnicity and LGBTQ People in Brighton & Hove Community Engagement and Consultation Report June 2018 Switchboard’s Health & Inclusion Project in partnership with The Trust for Developing Communities 1 INTERSECTIONALITY: RACE/ETHNICITY AND LGBTQ IDENTITY IN BRIGHTON & HOVE Brighton and Hove NHS Clinical Commissioning Group (BH CCG) and Brighton and Hove City Council (BHCC) have commissioned the Trust for Developing Communities (TDC) and the Health and Inclusion Project (HIP) at Switchboard to conduct a series of consultation and engagement activities with local communities. The aim is to use the information gathered to feed into local service commissioning, planning and delivery. This report was conducted in partnership by TDC and HIP, under the theme of ‘intersectionalities’. The consultation explored the intersection between race/ethnicity and LGBTQ communities in Brighton & Hove, with a specific focus on experiences of work and employment. Please note, the following report presents information about the consultation and engagement work conducted by TDC and HIP and should not be taken as a position statement of any participating organisation. Switchboard’s Health and Inclusion Project and the Trust for Developing Communities are extremely grateful to all partners who contributed insights and energy to this consultation, especially the community advisory panel, Brighton QTIPOC Narratives, Brighton & Hove’s LGBTQ groups, and Stonewall. 2 CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. -

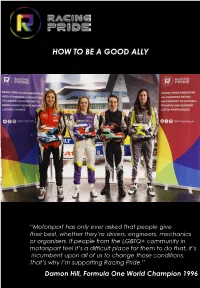

Being a Good Ally

HOW TO BE A GOOD ALLY “Motorsport has only ever asked that people give their best, whether they’re drivers, engineers, mechanics or organisers. If people from the LGBTQ+ community in motorsport feel it’s a difficult place for them to do that, it’s incumbent upon all of us to change those conditions. That’s why I’m supporting Racing Pride.” Damon Hill, Formula One World Champion 1996 Golden rule: It is up to everyone to define their own identity using their own terms so their terms are the ones you should use for them. WHAT DOES LGBTQ+ MEAN? LGBTQ+ is a broad term for those who would not define themselves as being heterosexual and/or wholly or partially reject binary ‘male’/‘female’ gender expressions and gender identities. It includes those who are: Lesbian – women who are romantically and/or sexually attracted to other women. Gay – men who are romantically and/or sexually attracted to other men. Some women who are attracted to other women also prefer to use the term gay. The majority of the LGBTQ+ community prefer ‘gay’ to ‘homosexual’, because ‘homosexual’ has associations with the notion that same sex attraction is a medical condition to be treated. It’s okay to say gay! Bisexual – those who are romantically or sexually attracted to partners of either sex. Trans – those whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. Trans people will often go through a process of transitioning: steps taken to live in the gender with which they identify. Each person’s transition will involve different elements and may or may not involve medical intervention. -

SINGLE EQUALITY SCHEME 2008-2011 Contacting Suffolk Police Authority

SINGLE EQUALITY SCHEME 2008-2011 Contacting Suffolk Police Authority The Authority welcomes comments on the Single Equality Scheme. If you would like a copy of the Scheme, or wish to discuss any aspect of it, please contact the Chief Executive to the Authority: Chief Executive Suffolk Police Authority Police Headquarters Martlesham Heath IPSWICH Suffolk IP5 3QS Telephone: 01473 782777 Email: [email protected] Website: www.suffolkpoliceauthority.org.uk Other Formats and Languages The Scheme can be made available in other formats on request e.g. large print, Braille, audiotape or compact disk. The Authority will also consider the provision of a summary of the document in any of the following languages, on request. 2 Foreword We are pleased to introduce Suffolk Police Authority’s Single Equality Scheme. It brings together in one document the existing statutory duties in relation to race, disability and gender equality, and goes beyond them to include other legislative requirements for other strands of diversity, i.e. age, religion or belief and sexual orientation. It also addresses how the Authority will meet its new duties under the Police and Justice Act 2006 to promote equality and diversity within both their Force and the Authority, and monitor the Force’s compliance with duties imposed by the Human Rights Act 1998. We welcome this harmonisation of our approach to diversity, equality and human rights. The Scheme is more than just a way of satisfying our legal responsibilities. It is the framework of standards and principles that will be applied by the Authority to ensure that quality policing services are delivered in a manner which is fair for all sections of the community, that people are treated with respect and that the workforce reflects the community it serves. -

Switchboard: the LGBT+ Helpline Archive (SB)

Switchboard: the LGBT+ Helpline Archive (SB) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Nicky Hilton September 2016 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents p.2 Collection Level Description p.3 SB/1: Governance p.5 SB/2: Finance and Grants p.29 SB/3: Constitution and Legal Status p.32 SB/4: Volunteer Administration p.33 SB/5: Call Logs p.35 SB/6: Information for Phone Work p.62 SB/7: Reports p.83 SB/8: Correspondence from Service Users p.84 SB/9: General Correspondence p.86 SB/10: Conferences p.89 SB/11: Fundraising Activities p.93 SB/12: Promotional Activities p.98 SB/13: Photographs p.106 SB/14: Newsletters and Histories p.116 SB/15: Partnerships p.119 SB/16: Press Cuttings Regarding Switchboard p.123 SB/17: Un-assigned Series n/a SB/18: FROGS: Friends of Switchboard p.124 SB/19: Dudley Cave Archive p.126 2 SB Switchboard - the LGBT+ Helpline 1974-2015 Name of Creator: Switchboard - the LGBT+ Helpline Extent: 111 Boxes, 4 Rolls Administrative/Biographical History: Switchboard was established in 1974 as 'London Gay Switchboard', taking its first call on 4 March. The purpose of the organisation was to provide information and advice for the gay and lesbian community. The helpline quickly expanded both in terms of calls received and it's remit, although it remained a nominally local, rather than national, helpline for many years. Switchboard was a key source of advice for gay men who faced discrimination in all areas of life throughout the 1970s, as well as being at the forefront of AIDS awareness campaigns in the 1980s. -

The Politics of Eradication and the Future of Lgbt Rights

THE POLITICS OF ERADICATION AND THE FUTURE OF LGBT RIGHTS NANCY J. KNAUER* ABSTRACT The debate over LGBT rights has always been a debate over the right of LGBT people to exist. This Article explores the politics of eradication and the institutional forces that are brought to bear on LGBT claims for visibility, rec- ognition, and dignity. In its most basic form, the desire to eradicate LGBT identities ®nds expression in efforts to ªcureº or ªconvertº LGBT people, espe- cially LGBT youth. It is also re¯ected in present-day policy initiatives, such as the recent wave of anti-LGBT legislation that has been introduced in states across the country. The politics of eradication has prompted the Trump admin- istration to reverse many Obama-era initiatives that recognized and protected LGBT people. It is also at the heart of a proposal to promulgate a federal de®- nition of gender that could remove any acknowledgment of transgender people from federal programs and civil rights protections. This Article is divided into three sectionsÐeach uses a distinct institutional lens: science, law, and religion. The ®rst section engages the ®eld of science, which helped produce the initial iterations of LGBT identity. It charts the evolu- tion of scienti®c theories regarding LGBT people and places a special emphasis on how these theories were used to further both LGBT subordination and liber- ation. The second section shifts the focus to the legal battles over LGBT rights that began in the 1990s at approximately the same time the scienti®c community started its exploration of the biological underpinnings of LGBT identities. -

Representations of Same-Sex Love in Public History By

Representations of Same-Sex Love in Public History By Claire Louise HAYWARD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Kingston University November 2015 2 Contents Page Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 List of abbreviations 6 Introduction 7 Chapter One ‘Truffle-hounding’ for Same-Sex Love in Archives 40 Chapter Two Corridors of Fear and Social Justice: Representations of Same-Sex Love in Museums 90 Chapter Three Echoes of the Past in Historic Houses 150 Chapter Four Monuments as les lieux de mémoire of Same-Sex Love 194 Chapter Five #LGBTQHistory: Digital Public Histories of Same-Sex Love 252 Conclusion 302 Appendix One 315 Questionnaire Appendix Two 320 Questionnaire Respondents Bibliography 323 3 Abstract This thesis analyses the ways in which histories of same-sex love are presented to the public. It provides an original overview of the themes, strengths and limitations encountered in representations of same-sex love across multiple institutions and examples of public history. This thesis argues that positively, there have been many developments in archives, museums, historic houses, monuments and digital public history that make histories of same-sex love more accessible to the public, and that these forms of public history have evolved to be participatory and inclusive of margnialised communities and histories. It highlights ways that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans*, Queer (LGBTQ) communities have contributed to public histories of same-sex love and thus argues that public history can play a significant role in the formation of personal and group identities. It also argues that despite this progression, there are many ways in which histories of same-sex love remain excluded from, or are represented with significant limitations, in public history. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES The Discursive Production of Homosexual Regulation by Graham Neil Baxendale Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2013 1 2 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES Doctor of Philosophy THE DISCURSIVE PRODUCTION OF HOMOSEXUAL REGULATION By Graham Neil Baxendale This thesis explores the pivotal place of the 1885 Labouchère Amendment and the 1967 Sexual Offences Act in the discourse of homosexual regulation presented by 20th century homophile histories. These twin events of ‘criminalisation’ and ‘decriminalisation’ are revisited to explore how and why they occurred and how they came to assume such a central position in both academic and popular understanding. The thesis draws on two streams of evidence. The literature on homosexual regulation is examined to establish the claims that are made about Labouchère Amendment and the Sexual Offences Act and the place that they are accorded, and the relationship that is established between them, within widely accepted homophile histories of the UK.