The Bristol Slave Traders: a Collective Portrait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11K Donation from the DPS to Help LGBT Young People in Brighton and Hove Find a Home Through YMCA Downslink Group - Youth Advice Centre

Computershare Investor Services PLC The Pavilions Bridgwater Road Bristol BS99 6ZZ Telephone + 44 (0) 870 702 0000 Facsimile + 44 (0) 870 703 6101 www.computershare.com News Release Monday 27 February 2017 Date: Subject: £11k donation from The DPS to help LGBT young people in Brighton and Hove find a home through YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre Bristol, Monday 27 February 2017 – An £11,000 donation by The Deposit Protection Service (The DPS) will fund specialist support from YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre for LGBT young people in Brighton and Hove to help them find a home, the UK’s largest protector of tenancy deposits has announced. The Centre will train volunteers one-to-one to become ‘peer mentors’ and provide support to other members of the local LGBT community. Daren King, Head of Tenancy Deposit Protection at The DPS, said: “83,000 young people experience homelessness every year and the South East has the second highest rate of homeless applications in England. “As a result, we’re delighted to be supporting YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre’s fantastic work in helping LGBT young people in Brighton and Hove find a home.” YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre is a “one-stop shop” for advice and information for young people aged 13-25 years old in the City of Brighton and Hove. Julia Harrison, Advice Services Manager at YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre, said: “LGBT young people account for 13% of the total number of clients accessing our housing service, with a 50% increase in transgender clients since April 2016. -

East Coast Modern a Route for Train Simulator – Dovetail Games

www.creativerail.co.uk East Coast Modern A Route for Train Simulator – Dovetail Games Contents A Brief History of the Route Route Requirements Scenarios Belmont Yard – York Freight Doncaster – Newark Freight Grantham – Doncaster Non-Stop Hexthorpe – Marshgate Freight Newark – Doncaster Works Peterborough – Tallington Freight Peterborough – York Non-Stop Selby – York York – Doncaster Works Operating Notices Acknowledgements © Copyright CreativeRail. All rights reserved. 2018. www.creativerail.co.uk A Brief History of the Route The first incarnation of the East Coast Main Line dates back to 1850 when London to Edinburgh services became possible on the completion of a permanent bridge over the River Tweed. However, the route was anything but direct, would have taken many, many hours and would have been exhausting. By 1852, the Great Northern Railway had completed the 'Towns Line' between Werrington (Peterborough) and Retford, which saw journey times between York and London of five hours. Edinburgh to London was a daunting eleven. Over time, the route has endured harsh periods, not helped by two world wars. It only benefited from very little improvement. Nevertheless, journey times did shrink. Names and companies synonymous with the route, such as, LNER and Gresley have secured their place in history, along with the most famous service - 'The Flying Scotsman'. Motive power also developed with an ever increasing calibre including A3s, A4s Class 55s and HSTs that have powered expresses through the decades. The introduction of HST services in 1978 saw the Flying Scotsman reach Edinburgh in only five hours. A combination of remodelling, track improvements and full electrification has seen a further reduction to what it is today, which sees the Scotsman complete the 393 miles in under four and a half hours in the capable hands of Class 91 and Mk4 IC225 formations. -

Stoke-On-Trent Group Travel Guide

GROUP GUIDE 2020 STOKE-ON-TRENT THE POTTERIES | HERITAGE | SHOPPING | GARDENS & HOUSES | LEISURE & ENTERTAINMENT 1 Car park Coach park Toilets Wheelchair accessible toilet Overseas delivery Refreshments Stoke for Groups A4 Advert 2019 ART.qxp_Layout 1 02/10/2019 13:20 Page 1 Great grounds for groups to visit There’s something here to please every group. Gentle strolls around award-winning gardens, woodland and lakeside walks, a fairy trail, adventure play, boat trips and even a Monkey Forest! Inspirational shopping within 77 timber lodges at Trentham Shopping Village, the impressive Trentham Garden Centre and an array of cafés and restaurants offering food to suit all tastes. There’s ample free coach parking, free entrance to the Gardens for group organisers and a £5 meal voucher for coach drivers who accompany groups of 12 or more. Add Trentham Gardens to your days out itinerary, or visit the Shopping Village as a fantastic alternative to motorway stops. Contact us now for your free group pack. JUST 5 MINS FROM J15 M6 Stone Road, Trentham, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire 5 minutes from J15 M6, Sat Nav Post Code ST4 8JG Call 01782 646646 Email [email protected] www.trentham.co.uk Stoke for Groups A4 Advert 2019 ART.qxp_Layout 1 02/10/2019 13:20 Page 1 Welcome Contents Introduction 4 WELCOME TO OUR Pottery Museum’s 5 & Visitor Centres Factory Tours 8 CREATIVE CITY Have A Go 9 Opportunities Manchester Stoke-on-Trent Pottery Factory 10 Great grounds BirminghamStoke-on-Trent Shopping General Shopping 13 Welcome London Stoke-on-Trent is a unique city affectionately known Gardens & Historic 14 for groups to visit as The Potteries. -

Appendix 6 Performance Indicator and CIPFA Data Comparisons BVPI Comparisons

Appendix 6 Performance Indicator and CIPFA Data Comparisons BVPI Comparisons Southend-on-Sea vs CPA Environment High Scorers / Nearest Neighbours / Unitaries BV 106: Percentage of new homes built on previously developed land 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Southend-on-Sea 100 100 100 CPA 2002 Environment score 3 or 4 in unitary authorities, by indicator 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Blackpool 56.8 63 n/a Bournemouth 94 99 n/a Derby 51 63 n/a East Riding of Yorkshire 24.08 16.64 n/a Halton 27.48 49 n/a Hartlepool 40.8 56 n/a Isle of Wight 84 86 n/a Kingston-upon-Hull 40 36 n/a Luton 99 99.01 n/a Middlesbrough 74.3 61 n/a Nottingham 97 99 n/a Peterborough 79.24 93.66 n/a Plymouth 81.3 94.4 n/a South Gloucestershire 41 44.6 n/a Stockton-on-Tees 33 29.34 n/a Stoke-on-Trent 58.4 61 n/a Telford & Wrekin 54 55.35 n/a Torbay 39 58.57 n/a CIPFA 'Nearest Neighbour' Benchmark Group 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Blackpool 56.8 63 n/a Bournemouth 94 99 n/a Brighton & Hove 99.7 100 n/a Isle of Wight 84 86 n/a Portsmouth 98.6 100 n/a Torbay 39 58.57 n/a Unitaries 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Unitary 75th percentile 94 93.7 n/a Unitary Median 70 65 n/a Unitary 25th percentile 41 52.3 n/a Average 66.3 68.7 n/a Source: ODPM website BV 107: Planning cost per head of population. -

Peterborough City Council Orangetek - ARIALED with Telensa CMS

ARIALED Peterborough City Council OrangeTek - ARIALED with Telensa CMS November 2014 “This was a great opportunity to show case the benefits of LED Lighting – Improving lighting levels, Reducing Energy Cost and Emissions, whilst improving the city Landscape for Residents. OrangeTek LED Luminaires perform exceptionally well, meeting Lighting design needs and offer personalised solutions and services that they truly deliver on their commitments.” Steve Biggs IEng MILP Senior Engineer/Technical Lead at Skanska UK November 2014 Peterborough City Council Anticipate Savings of more than £1.2 million per Annum Peterborough City Council Residential and Traffic Route Lighting. installed by Skanska ARIALED by OrangeTek In excess of 7,000 units installed in the past 2 Yrs. Project Details Projected Savings Peterborough, have installed just over 7,000 Orangetek The programme is due to be completed by February LED luminaires in the last two years of a total inventory 2016. of street lights being 33,000 units. Once complete, the new lamps will help the council cut Nearly 85% of Orangetek LED luminaries installed are on the city's street lighting bill by at least 57 per cent and residential roads, initially the older TERRALED model help reduce carbon emissions by more than 5,300 tons containing 24 & 36 LEDs. In March 2013 the TERRALED per Annum. installation ceased and replaced on the contract with the more efficient ARIALED, containing 20 or 30 LEDs, Street lighting costs the city council £2 million each replacing the 35W SOX, 50W SON luminaries. year. Based on estimated savings of about £1.2 million per year, the street lamp replacement is expected to Average savings are close to 50% without the utilisation pay for itself in just over 10 years (total cost of new of their CMS system (Telensa CMS). -

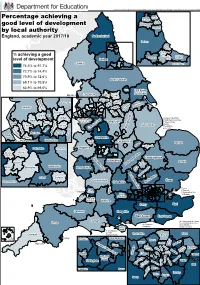

Percentage Achieving a Good Level of Development by Local Authority

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO © Crown copyright and database right 2018 All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100038433 North Newcastle Tyneside Percentage achieving a upon Tyne South Tyneside good level of development Gateshead Sunderland by local authority England, academic year 2017/18 Northumberland Durham Ha rtle po ol Stockton- on- % achieving a good Tees Redcar & Darlington Middles- Cleveland level of development Durham brough Cumbria North Yorkshire 74.5% to 91.7% 72.7% to 74.4% 70.9% to 72.6% North Yorkshire 69.1% to 70.8% 63.9% to 69.0% York East Riding of Yorkshire Blackpool Lancashire Bradford Leeds 1 w B i t la Calderdale d h s iel c f D k e ke h Calderdale le a ort e a b W N ir u k r sh r ir te ln w r s co n K y a Lin 2 Lancashire e rnsle nc n Ba R o o D S t K h h i e e rk f r e Rochdale fie h r le l a i e d m Bury s h Bolton s Oldham m 1 Kingston Upon Hull Cheshire West st a 2 North East Lincolnshire Wigan a h g 3 Stoke-on-Trent r & Chester E Derbyshire n Sefton Salford e e i K t ir t 4 Derby s h t n Lincolnshire St Helens e Tameside s 5 Nottingham o e o h w d h L r c N 6 Leicester i o e C v s ff n ir e l a h 3 r e ra s p y T M y o b 5 o Warrington Stockport r l e 4 Wirral D Halton Staffordshire Cheshire West & Chester Cheshire East Telford & Wrekin Leicestershire nd Norfolk tla 6 Ru Peterborough Staffordshire Leicestershire Shropshire Wolver- Walsall ire hampton sh W on Cambridgeshire o pt rc Warwickshire am Sandwell es rth Suffolk te o Bedford rs N Warwickshire h n s to e -

Sources of Help in North Somerset

Sources of Help in North Somerset National Organisations Mental Health First Aid Website of English Mental First Aid programme. News, updates, useful information and more. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 020 7250 8062 Website: www.mhfaengland.org Teacher Support Network Online advice and information for teachers. Telephone: 08000 562 561 (24/7 helpline number) Website: http://teachersupport.info/ Samaritans Samaritans provides confidential emotional support, 24 hours a day for people who are experiencing feelings of distress or despair, including those that may lead to suicide. You don't have to be suicidal to call us. We are here for you if you're worried about something, feel upset or confused, or you just need to talk to someone. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 08457 90 90 90 (24/7 helpline number) Website: www.samaritans.org MIND Mental health charity providing advice and information. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0300 123 3393 (9am-5pm Monday to Friday) Website: www.mind.org.uk SANE Charity to improve the lives of those affected by mental illness. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0845 767 8000 (24/7 helpline number) Website: http://www.sane.org.uk/home Cruse Bereavement Care Online advice and information. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0844 477 9400 Website: www.crusebereavementcare.org.uk Local Organisations Positive Step Positive Step offers support for people with common mental health problems through self help materials, psycho educational courses and one to one help. The service is accessed through GPs, or by contacting them directly. Positive Step Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust The Coast Resource Centre Diamond Batch Weston-super-Mare BS24 7FY Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 688 8010 Website: http://positivestep.org.uk Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health NHS Trust Manages mental health services in the South West. -

The Bristol Team

Thank You: The Team The Bristol Team Charrette Facilitators: Chris Nadeau Dan Paradis Paul Fraser jr. Nobis Engineering. Planning Board Chair Board of Selectmen Christopher Williams Concord, NH Christopher P. Williams Architects Steve Pernaw Paul Weston Joe Denning PLLC Pernaw Associates Town Manager Board of Selectmen Meredith, NH Concord, NH Michelle Bonsteel Christina McClay Jeffrey Taylor Mara Robinson Jeffrey Taylor and Associates Mara Landscape Design LLC Land Use Enforcement Officer Assessing Clerk Concord, NH Newport, NH Claire Moorhead Jeff Chartier Team Members: Karen Schott Community Economic Development Coordinator Water/Waste Water Superintendant Karen Fitzgerald CN Carley Architects FitzDesign inc. Concord NH Heidi Millbrand Mark Bucklin Francestown, NH Linda Wilson Chamber of Commerce President Superintendant. of Highways Nancy Mayville Division of Historic Resources Jan Laferriere Highway Department Crew New Hampshire Department of State of New Hampshire Transporttaion Concord. NH Recording Secretary Steve Favorite Concord, NH The Bristol Historic Society Claire Moorhead Corey Johnston Mason Westfall John Clark Northpoint Engineering, LLC Pembroke, NH Don Millbrand Police Chief Gene McCarthy, PE Board of Selectmen Norm Skantze McFarland-Johnson Inc. Bruce Van Derven former Fire Chief Concord, NH Board of Selectmen Peter Middleton Martini Northern Portsmouth NH Bristol, New Hampshire Design Charrette Sponsored by: Plan NH Town of Bristol, NH September 19 & 20, 2008 Bristol Charrette 2 Plan NH opposed to the details of how a particular building would actually be constructed. The Charrette process blends the broad experience of design professionals with local citizens’ Bristol Charrette detailed knowledge of their community to produce a plan of action to address a particular development issue within the community. -

Days & Hours for Social Distance Walking Visitor Guidelines Lynden

53 22 D 4 21 8 48 9 38 NORTH 41 3 C 33 34 E 32 46 47 24 45 26 28 14 52 37 12 25 11 19 7 36 20 10 35 2 PARKING 40 39 50 6 5 51 15 17 27 1 44 13 30 18 G 29 16 43 23 PARKING F GARDEN 31 EXIT ENTRANCE BROWN DEER ROAD Lynden Sculpture Garden Visitor Guidelines NO CLIMBING ON SCULPTURE 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. Do not climb on the sculptures. They are works of art, just as you would find in an indoor art Milwaukee, WI 53217 museum, and are subject to the same issues of deterioration – and they endure the vagaries of our harsh climate. Many of the works have already spent nearly half a century outdoors 414-446-8794 and are quite fragile. Please be gentle with our art. LAKES & POND There is no wading, swimming or fishing allowed in the lakes or pond. Please do not throw For virtual tours of the anything into these bodies of water. VEGETATION & WILDLIFE sculpture collection and Please do not pick our flowers, fruits, or grasses, or climb the trees. We want every visitor to be able to enjoy the same views you have experienced. Protect our wildlife: do not feed, temporary installations, chase or touch fish, ducks, geese, frogs, turtles or other wildlife. visit: lynden.tours WEATHER All visitors must come inside immediately if there is any sign of lightning. PETS Pets are not allowed in the Lynden Sculpture Garden except on designated dog days. -

South Gloucestershire Council Health & Wellbeing Division

Annex B2 South Gloucestershire Council Health & Wellbeing Division Emergency Contraception Service Specification 2014/15 Programme Lead: Lindsey Thomas Tel: 01454 864664 Email: [email protected] 1. Service Background The provision of sexual health services in community pharmacies contributes to the following key local and national health priorities: reducing the rate of under 18 conceptions reducing STI rates amongst young people Increasing the number of Chlamydia diagnoses Outcomes indicated in ‘A Framework for Sexual Health Improvement in England’ (Department of Health 2013) Meeting the local Chlamydia screening target for 15-24 year olds. All community pharmacies are required to provide some sexual health services as part of their essential services, e.g. promotion of healthy lifestyles, providing opportunistic sexual health advice in Public Health campaigns, signposting people to other services (including Contraception and Sexual Health Services [CaSH], Genito-Urinary Medicine [GUM] and maternity access), and support for self-care. This specification for emergency hormonal contraception services in pharmacies builds on these essential services, to provide a full and co-ordinated range of sexual health services to young people. This Service will operate from 1st April 2014 until 31st March 2015. It will then be reviewed in the light of any changes to pharmacy provision, success of the service and healthcare needs of the local population. 2. Service Aims To improve access to emergency contraception and sexual health -

Terms NL Clinic 2

TOGIP Ltd Clinic Terms and Conditions • 4.1.1. physical in-person testing support occurring from a site either controlled by us or a third party. • 5.7.5. We will not be liable to you for any injury or damage caused to you, any third party or any property 9.2. More significant changes to the services and these terms. We may decide to make more significant changes to 13.1. We may cancel the appointment at any time by writing to you if: • 4.1.2. any other services advertised on our website, or at our premises. by your failure to follow the instructions of the swab practitioner or your negligent or reckless use of the testing kits. the services that we provide, but if we do so we will notify you and you may then contact us to cancel the booking • 13.1.1. you do not make any payment to us when it is due and you still do not make payment within 7 days 16.4. We will only retain your personal information for as long as is necessary to provide the services to you. t/a • 4.1.3. Assistance to self-test such as blood tests and swabs. 6. HOME TESTING KITS before the changes take effect and receive a refund for any services paid for but not yet received. of us reminding you that payment is due. 16.5. For more information on how we may process your personal data, please refer to our privacy policy on the NL Clinic Peterborough • 4.1.4. -

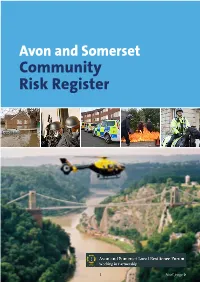

Community Risk Register Go to Contents Page (Click)

Avon and Somerset Community Risk Register Go to contents page (click) Avon and Somerset Community Risk Register 1 Avon and Somerset Community Risk Register Contents (Click on chapters) Introduction and Context ...........................................................................................................3 1. Emergency Management Steps ......................................................................................7 2. Avon and Somerset’s Top Risks ........................................................................................9 2.1 Flooding .............................................................................................................................................................10 2.2 Animal Disease ...............................................................................................................................................13 2.3 Industrial Action .............................................................................................................................................14 2.4 Pandemic Influenza ......................................................................................................................................15 2.5 Adverse Weather ............................................................................................................................................17 2.6 Transport Incident (including accidents involving hazardous materials) ..............................19 2.7 Industrial Site Accidents .............................................................................................................................22