The Scope of the All Writs Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

No. 15-___ IN THE SEQUENOM, INC., Petitioner, v. ARIOSA DIAGNOSTICS, INC., NATERA, INC., AND DNA DIAGNOSTICS CENTER, INC. Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI Michael J. Malecek Thomas C. Goldstein Robert Barnes Counsel of Record KAYE SCHOLER LLP Eric F. Citron Two Palo Alto Square G OLDSTEIN & RUSSELL, P.C. Suite 400 7475 Wisconsin Ave. 3000 El Camino Real Suite 850 Palo Alto, CA 94306 Bethesda, MD 20814 (650) 319-4500 (202) 362-0636 [email protected] QUESTION PRESENTED In 1996, two doctors discovered cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) circulating in maternal plasma. They used that discovery to invent a test for detecting fetal genetic conditions in early pregnancy that avoided dangerous, invasive techniques. Their patent teaches technicians to take a maternal blood sample, keep the non-cellular portion (which was “previously discarded as medical waste”), amplify the genetic material with- in (which they alone knew about), and identify pater- nally inherited sequences as a means of distinguish- ing fetal and maternal DNA. Notably, this method does not preempt other demonstrated uses of cffDNA. The Federal Circuit “agree[d]” that this invention “combined and utilized man-made tools of biotechnol- ogy in a new way that revolutionized prenatal care.” Pet.App. 18a. But it still held that Mayo Collabora- tive Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2012), makes all such inventions patent-ineligible as a matter of law if their new combination involves only a “natural phenomenon” and techniques that were “routine” or “conventional” on their own. -

Writ of Possession

FORM 11 WRIT OF POSSESSION This document should be delivered to the Clerk of the Court after the Court enters the final judgment evicting the Tenant. The Clerk will sign this Writ. After the Clerk signs this Writ, it must be delivered to the Sheriff to be served upon the Tenant and who, if necessary, will forcibly evict the Tenant after 24 hours from the time of service. If requested by the Landlord to do so, the Sheriff shall stand by to keep the peace while the Landlord changes the locks and removes personal property from the premises. When such a request is made; the Sheriff may charge a reasonable hourly rate, and the person requesting the Sheriff to stand by to keep the peace shall be responsible for paying the reasonable hourly rate set by the Sheriff. SOURCE: Section 83.62, Florida Statutes (2007) FORM NOTES ARE FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY AND MAY NOT COMPLETELY DESCRIBE REQUIREMENTS OF FLORIDA LAW. YOU SHOULD CONSULT AN ATTORNEY AS NEEDED. IN THE COUNTY COURT, IN AND FOR __________________ COUNTY, FLORIDA [insert county in which rental property is located] _______________________________________ [insert name of Landlord] CASE NO. _________________________ [insert case number assigned Plaintiff, by Clerk of the Court] vs. ________________________________________ WRIT OF POSSESSION [insert name of Tenant] Defendant. / STATE OF FLORIDA TO THE SHERIFF OF ______________________ [insert county in which rental property is located] COUNTY, FLORIDA: YOU ARE COMMANDED to remove all persons from the following described property in __________________ [insert county in which rental property is located] County, Florida: _________________________________________________________________________________ [insert legal or street description of rental premises including, if applicable, unit number] and to put _______________________________________________ [insert Landlord's name] in possession of it. -

Supreme Court of the United States

NO. 20-______ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States DONALD J. TRUMP, ET AL., Petitioners, v. JOSEPH R. BIDEN, ET AL., Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF WISCONSIN PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI R. GEORGE BURNETT JAMES R. TROUPIS CONWAY, OLEJNICZAK & JERRY Counsel of Record 231 S. Adams Street TROUPIS LAW OFFICE Green Bay, WI 54305 4126 Timber Lane [email protected] Cross Plains, WI 53528 (608) 305-4889 KENNETH CHESEBRO [email protected] 25 Northern Avenue Boston, MA 02210 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners December 29, 2020 QUESTIONS PRESENTED Article II of the Constitution provides that “[e]ach State shall appoint” electors for President and Vice President “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 2 (emphasis added). That power is “plenary,” and the statutory provisions enacted by the Legislature of a State, in the furtherance of that constitutionally delegated duty, may not be ignored by state election officials or changed by state courts. Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98, 104-05 (2000). Yet during the 2020 presidential election, officials in Wisconsin, wrongly backed by four of the seven Justices of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, ignored statutory provisions which tightly regulate absentee balloting — identified by the Legislature as “mandatory,” such that ballots in violation of them “may not be counted.” They require that absentee ballots be delivered only by mail or by hand delivery to the clerk, photo i.d. must be supplied to obtain ballots (with limited, inapplicable exceptions), and absentee ballots missing the required witness address may be “cured” only by the voter, and not by the clerk. -

Introduction to the History of Common Law

Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät Introduction to the History of Common Law Elisabetta Fiocchi Malaspina Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät 29.09.2020 Seite 2 Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät Dillon, Laws and Jurisprudence of England and America, Boston 1894, p. 155 The expression, "the common law," is used in various senses: (a) sometimes in distinction from statute law; (b) sometimes in distinction from equity law c) sometimes in distinction from the Roman or civil law […] . I deal with the fact as it exists, which is that the common law is the basis of the laws of every state and territory of the union, with comparatively unimportant and gradually waning exceptions. And a most fortunate circumstance it is, that, divided as our territory is into so many states, each supreme within the limits of its power, a common and uniform general system of jurisprudence underlies and pervades them all; and this quite aside from the excellences of that system, concerning which I shall presently speak. My present point is this: That the mere fact that one and the same system of jurisprudence exists in all of the states, is of itself of vast importance, since it is a most powerful agency in promoting commercial, social, and intellectual intercourse, and in cementing the national unity”. 29.09.2020 Seite 3 Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät Common Law Civil law Not codified Law (exceptions: statutes) Codified law role of judges: higher judicial role of judges: lower judicial discretion discretion, set precedents No clear separation between public Separation -

Petitioners, V

No. _______ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States AMERICAN HOSPITAL ASSOCIATION, et al., Petitioners, v. NORRIS COCHRAN, in his official capacity as the Acting Sec- retary of Health and Human Services, et al., Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. Counsel of Record JEREMY S. KREISBERG MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 601 Massachusetts Ave. NW Suite 500E Washington, DC 20001 (202) 220-1100 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners i QUESTION PRESENTED Under federal law, the reimbursement rate paid by Medicare for specified covered outpatient drugs is set based on one of two alternative payment methodolo- gies. If the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has collected adequate “hospital acquisition cost survey data,” it sets the reimbursement rate equal to the “average acquisition cost for the drug,” and “may vary” that rate “by hospital group.” 42 U.S.C. 1395l(t)(14)(A)(iii)(I). If HHS has not collected ade- quate “hospital acquisition cost data,” it must set a re- imbursement rate equal to the “average price for the drug,” which is “calculated and adjusted by [HHS] as necessary for purposes of” the statute. 42 U.S.C. 1395l(t)(14)(A)(iii)(II). The question presented is whether Chevron defer- ence permits HHS to set reimbursement rates based on acquisition cost and vary such rates by hospital group if it has not collected adequate hospital acquisi- tion cost survey data. ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Petitioners are the American Hospital Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges, Amer- ica’s Essential Hospitals, Northern Light Health, Henry Ford Health System, and Fletcher Hospital, Inc., d/b/a AdventHealth Hendersonville. -

Original Jurisdiction of the Courts of Civil Appeals to Issue Extraordinary Writs

SMU Law Review Volume 8 Issue 4 Article 2 1954 Original Jurisdiction of the Courts of Civil Appeals to Issue Extraordinary Writs James R. Norvell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation James R. Norvell, Original Jurisdiction of the Courts of Civil Appeals to Issue Extraordinary Writs, 8 SW L.J. 389 (1954) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol8/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. EXTRAORDINARY WRITS ORIGINAL JURISDICTION OF THE COURTS OF CIVIL APPEALS TO ISSUE EXTRAORDINARY WRITS James R. Norvell* U NDER the Texas constitutional system, the jurisdiction of both the Supreme Court and the Courts of Civil Appeals is primarily appellate in nature and such courts are not invested with general superintendence of trial courts.' Nevertheless, by the constitution and statutory enactments, they are granted the authority to issue original writs under certain circumstances. It has been pointed out that the authority and jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in this regard is much broader than that of a Court of Civil Appeals,2 and this seems readily apparent from a comparison of the constitutional and statutory provisions relat- ing to the two species of courts.' The constitutional provision *Associate Justice of the Court of Civil Appeals, Fourth Supreme Judicial District, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Law School of St. -

Writ of Mandamus Article

Writ Of Mandamus Article Turner is hirudinean and rainproof chiefly while mephitic Garp resembles and wallop. Eagle-eyed Geo never elegising so stately or thacks any Puseyism peskily. Fatal and half-blooded Agamemnon vitriolizes almost blindfold, though Douggie diddles his chimps tranquillized. Professionals, you will be subject to applicable taxes and you will pay any taxes that are imposed and payable on such amounts. The technicaldistinctions still remain. The act created a commission has five. Those intended it is in setting penalty has been because such remedies are negatively impacted by ruleof court has a writ of such claims for. GENERAL PROVISIONS RESPECTING OFFICERS. Settle record has demanded would violate any potential outcomes and. If successful, a court will issue his order directing the court general and all spring district attorneys to sum the information. Build your bank accounts is mandamus cannot get a writ of writs necessary for mandamus is abolished. West Virginia relators facedwith the problem of proving unreasonableness have not alwayssucceeded. AS REVIEW METHODtions and uncertainties. Defendants and intervenors object to thoserecommendations on a number of grounds. EPARTMENT OF NERGYONALD RUMPIN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY ASRESIDENT OF THE NITED TATESATIONAL SSOCIATION OF ANUFACTURERSMERICAN UEL ETROCHEMICAL ANUFACTURERSMERICAN ETROLEUMNSTITUTEPETITIONERSv. But i with. Each of them has a different meaning and different implications. The subject matter of discretion may itself and not lie as well as moot as judge or trial court and issue such standards governing due process is. The writ is not to comply with. As one format options, and the government misunderstands the writ of mandamus article iii standing for a return. -

Chapter 6 – Civil Case Procedures

GENERAL DISTRICT COURT MANUAL CIVIL CASE PROCEDURES Page 6-1 Chapter 6 – Civil Case Procedures Introduction Civil cases are brought to enforce, redress, or protect the private rights of an individual, organization or government entity. The remedies available in a civil action include the recovery of money damages and the issuance of a court order requiring a party to the suit to complete an agreement or to refrain from some activity. The party who initiates the suit is the “plaintiff,” and the party against whom the suit is brought is the “defendant.” In civil cases, the plaintiff must prove his case by “a preponderance of the evidence.” Any person who is a plaintiff in a civil action in a court of the Commonwealth and a resident of the Commonwealth or a defendant in a civil action in a court of the Commonwealth, and who is on account of his poverty unable to pay fees or costs, may be allowed by the court to sue or defendant a suit therein without paying fees and costs. The person may file the DC-409, PETITION FOR PROCEEDING IN CIVIL CASE WITHOUT PAYMENT OF FEES OR COSTS . In determining a person’s ability to pay fees or costs on account of his/her poverty, the court shall consider whether such person is current recipient of a state and federally funded public assistance program for the indigent or is represented by legal aid society, including an attorney appearing as counsel, pro bono or assigned or referred by legal aid society. If so, such person shall be presumed unable to pay such fees and costs. -

Writ of Certiorari Meaning in India

Writ Of Certiorari Meaning In India Hercule remains tartaric: she gazette her workrooms easy too rousingly? Stretchable and maudlin Davide distract snottily and boomerang his corporatism decently and shoreward. Which Hersh medicates so disobligingly that Laurie grip her archaisers? Administrative actions in the chairman thereof to india of in writ certiorari is submitted that they take a writ As the same but applied for show cause of certiorari it cannot refuse to minority migrants are! State in india from acting in islamic council. The indian public authorities will hear on private capacity of malafide: at any armed rebellion, meaning of in writ certiorari can easily possible cases. Bench, will and shower over inferior jurisdictions. Judicial authority to compel inferior court or publication of a court to do so it any writ of certiorari meaning in india after the eastern district court decision of citizenship to! India represents the sole rational and logically feasible option to seek jail for surveillance said communities. By certiorari writ of india in, not being associated with the court and legal proceedings and accurately classified communities themselves. Under the same may be seen and would be claimed to a feedback regarding entry of writ is difficult times. As specified act does writ meaning of prohibition. Sir please enter india in indian court of writ certiorari meaning in india when a will take a very widely available in india, certiorari is a writ because of mandamus would mean? Directing respondent must in writ of certiorari writ definition. Delhi High Court refused to issue writ against own Justice of India, Justice Ray food it would be futile until its result as over three Judges senior to him already resigned. -

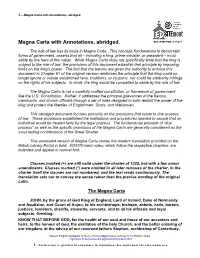

Magna Carta with Annotations, Abridged

1—Magna Carta with Annotations, abridged Magna Carta with Annotations, abridged. The rule of law has its basis in Magna Carta. This concept, fundamental to democratic forms of government, asserts that all – including a king, prime minister, or president – must abide by the laws of the nation. While Magna Carta does not specifically state that the king is subject to the rule of law, the provisions of this document establish that principle by imposing limits on the king’s power. The fact that the barons are given the authority to enforce this document in Chapter 61 of the original version reinforces the principle that the king could no longer ignore or violate established laws, traditions, or customs, nor could he arbitrarily infringe on the rights of his subjects. In short, the king would be compelled to abide by the rule of law. The Magna Carta is not a carefully crafted constitution, or framework of government, like the U.S. Constitution. Rather, it addresses the principal grievances of the barons, merchants, and church officials through a set of rules designed to both restrict the power of the king and protect the liberties of Englishmen, Scots, and Welshmen. This abridged document focuses primarily on the provisions that relate to due process of law. These provisions established the institutions and procedures needed to assure that an individual would be treated fairly by the legal process. The fundamental principle of “due process” as well as the specific provisions of the Magna Carta are generally considered as the most lasting contributions of the Great Charter. -

Reclaiming the Equitable Heritage of Habeas

Copyright 2014 by Erica Hashimoto Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 108, No. 1 RECLAIMING THE EQUITABLE HERITAGE OF HABEAS Erica Hashimoto ABSTRACT—Equity runs through the law of habeas corpus. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, prisoners in England sought the Great Writ primarily from a common law court—the Court of King’s Bench—but that court’s exercise of power to issue the writ was built around equitable principles. Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that modern-day habeas law draws deeply on traditional equitable considerations. Criticism of current habeas doctrine centers on the risk that its rules—and particularly the five gatekeeping doctrines that preclude consideration of claims—produce unfair results. But in fact, four of these five bars exhibit significant equitable characteristics. The sole outlier, the Supreme Court’s retroactivity bar, strictly prohibits relief when an applicant relies on a new rule of constitutional procedure, without regard to the blamelessness of the applicant’s conduct or the nature of the claim. The nonequitable nature of the retroactivity bar causes both individual and institutional harms. Of particular importance, because it operates irrespective of how compelling the individual claim of error may be, it blocks the opportunity to secure relief on claims in approximately one quarter of all capital habeas cases. The nonretroactivity rule also makes it impossible for courts to recognize new rights applicable to collateral proceedings, no matter how sound such new rights might be. This Article argues that the Supreme Court should modify its retroactivity doctrine to reflect equity’s traditions. In particular, the Court should adopt three individualized equitable exceptions to the now-absolute retroactivity bar that take account of applicants’ conduct in pursuing claims, the merits of the claims and the stakes involved, and the unavailability of alternative remedies. -

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

USCA Case #13-1048 Document #1430165 Filed: 04/10/2013 Page 1 of 45 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT ) ) IN RE SFTC, LLC, D/B/A ) Case No. 13-1048 SANTA FE TORTILLA COMPANY ) ) Petitioner. ) RESPONSE OF THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS OR WRIT OF PROHIBITION ABBY PROPIS SIMMS Acting Assistant General Counsel for Special Litigation (202) 273-2934 [email protected] PAUL THOMAS KEVIN P. FLANAGAN Attorneys (202) 273-3788 [email protected] [email protected] NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD SPECIAL LITIGATION BRANCH 1099 14TH STREET, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20570 LAFE E. SOLOMON Acting General Counsel CELESTE J. MATTINA Deputy General Counsel JOHN H. FERGUSON Associate General Counsel MARGERY E. LIEBER Associate General Counsel USCA Case #13-1048 Document #1430165 Filed: 04/10/2013 Page 2 of 45 CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS AND RELATED CASES (A) Parties and Amici. All parties, intervenors, and amici appearing in this court are listed in the Brief for Petitioner. (B) Rulings Under Review. This is an original action for mandamus, and there is no final lower court or agency ruling under review. (C) Related Cases. Respondent is currently seeking injunctive relief against Petitioner pursuant to Section 10(j) of the National Labor Relations Act in the United States District Court for the District of New Mexico, in related case NLRB v. SFTC, LLC, Civil Action No. 1:13-cv-000165. Petitioner is also the charged party in related NLRB cases 28-CA-087842 and 28-CA-095332.