A History of Market Rasen Railway Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

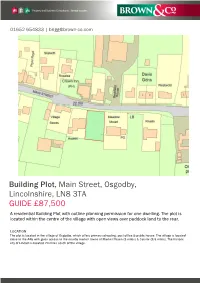

Building Plot, Main Street, Osgodby, Lincolnshire, LN8 3TA GUIDE £ 87,500 a Residential Building Plot with Outline Planning Permission for One Dwelling

01652 654833 | brigg@brown -co.com Building Plot, Main Street, Osgodby, Lincolnshire, LN8 3TA GUIDE £ 87,500 A residential Building Plot with outline planning permission for one dwelling. The plot is located within the centre of the village with open views over paddock land to the rear. LOCATION The plot is located in the village of Osgodby, which offers primary schooling, post office & public house. The village is located close to the A46 with gives access to the nearby market towns of Market Rasen (3 miles) & Caistor (8.5 miles). The historic city of Lincoln is located 20 miles south of the village. Building Plot , Main Street, Osgodby, Lincolnshire, GENERAL REMARKS and STIPULATIONS LN8 3TA Viewing: Please contact the Brigg office on 01652 654833. The Plot Hours of Business: The plot has a road frontage of 19m (62.5ft) with a depth of 32m Monday to Friday 9am - 5.30pm, Saturday 9am – 12.30pm. (105ft). Free Valuation: We would be happy to provide you with a free market appraisal of Planning Permission your own property should you wish to sell. Further information can The plot has Outline Planning Permission for the erection of one be obtained from Brown & Co, Brigg – 01652 654833. dwelling. Application number: 134753 , West Lindsey District Council, granted on the 12 th October 2016. A copy of the planning These particulars were prepared in November 2016. consent is available for inspection at the Agent’s Brigg office. Viewing of the site is highly recommended to appreciate the full The Plot from the rear elevation potential. Services Water, electricity and drainage are located to the front of the plot. -

Rail Lincs 67

Has Grantham event delivered a rail asset? The visit of record breaking steam locomotive, A4 pacific Mallard, to Grantham at the RailRail LincsLincs beginning of September, has been hailed an outstanding success by the organisers. Number 67 = October 2013 = ISSN 1350-0031 LINCOLNSHIRE With major sponsorship from Lincolnshire County Council, South Kesteven District Lincolnshire & South Humberside Branch of the Council and Carillion Rail; good weather and free admission, the event gave Grantham Railway Development Society N e w s l e t t e r high profile media interest, attracting in excess of 15,000 visitors (some five times the original estimate). Branch has a busy weekend at One noticeable achievement has been the reconstruction of a siding resulting in the clearing of an ‘eyesore’ piece of land at Grantham station, which forms a gateway to the Grantham Rail Show town. The success of the weekend has encouraged the idea for a similar heritage event Thank you to everyone who helped us The weekend was also a very in the future. over the Grantham Rail Show weekend. successful fund raising event which has However, when the piece of land was cleared and the Up side siding reinstated, it This year, the Rail Show was held in left our stock of donated items very became apparent that Grantham had, possibly, unintentionally received a valuable association with the Mallard Festival of depleted. If you have any unwanted items commercial railway asset. Here is a siding connected to the national rail network with Speed event at Grantham station, with a that we could sell at future events, we easy road level access only yards from main roads, forming the ideal location for a small free vintage bus service linking the two would like to hear from you. -

Millside Bardney Road,Wragby Market Rasen LN8 5QZ

Millside Bardney Road,Wragby Market Rasen LN8 5QZ welcome to Millside Bardney Road, Wragby Market Rasen **NO CHAIN** Situated approximately 10 miles north-west of Horncastle and 11 miles north-east of the historical cathedral city of Lincoln within the ever popular and sought after town of Wragby is this well appointed three bedroom detached bungalow benefiting from ample off-road parking and garage. Entrance Porch Entrance Hall Lounge / Diner 17' 5" x 9' 11" ( 5.31m x 3.02m ) Kitchen 18' 6" x 8' 7" ( 5.64m x 2.62m ) Rear Lobby 8' 7" x 5' 9" ( 2.62m x 1.75m ) Bedroom One 12' 1" x 11' 6" ( 3.68m x 3.51m ) Bedroom Two 17' 1" x 9' 11" ( 5.21m x 3.02m ) Bedroom Three 12' 1" x 10' ( 3.68m x 3.05m ) Ensuite Bathroom Outside To the front of the property there is a gravelled area with a variety of herbaceous shrubs and a gravelled driveway providing off-road parking leading to the rear garden. The rear garden is a generous size being predominantly laid to lawn with a variety of decorative shrubs, apple and pear trees, good size patio area ideal for seating and a decorative pond. Furthermore, there is a shed with full power and lighting and a summer house with full power and lighting; all of which is fully enclosed to perimeters. Garage With double doors. view this property online williamhbrown.co.uk/Property/LCR113161 welcome to Millside Bardney Road, Wragby Market Rasen **NO ONWARD CHAIN** Detached Bungalow Three Bedrooms Ensuite Wet Room & Separate Bathroom Well Maintained Rear Garden with Pond & Fruit Trees Tenure: Freehold EPC Rating: E £220,000 Please note the marker reflects the view this property online williamhbrown.co.uk/Property/LCR113161 postcode not the actual property see all our properties on zoopla.co.uk | rightmove.co.uk | williamhbrown.co.uk 1. -

Former Nat West Bank Premises, 7 Market Place, Market Rasen

Former Nat West Bank Premises, 7 • Retail Area Market Place, Market Rasen, • Offices Lincolnshire, LN8 3HJ • Staff Room £17,000 • Strong Room Storage • Toilets (TO LET VIA SUBLEASE) • Storage A prominent ground floor former bank with potential for a variety of uses, subject to planning. • Car Parking • Approx 172 sqm/1850 sqft NIA • EPC Rating C www.johntaylors.com LOCATION PLEASE NOTE: The town of Market Rasen is situated some 13 miles north east of Lincoln If measurements are critical to the purchaser they should be and some 16 miles south west of Grimsby. verified before proceeding with the purchase of this property. The property is located in the centre of the town overlooking its Market Square with surrounding occupiers including Cop-op, Lloyds Bank, Boots John Taylors have not tested any of the services or appliances Pharmacy, Cooplands Bakery and McColls Newsagents. and so offer no guarantees. Any carpets, curtains, furniture, fittings electrical and gas appliances, gas or light fittings or any ACCOMMODATION other fixtures not expressly stated in the sales particulars but may be available through separate negotiation. Floor plans are Retail Area 28'5" x 22'10" (8.66m x 6.97m) provided as a service to our customers and are a guide to the layout only, do not scale. Retail Area 11'3" x 7'10" (3.43m x 2.40m) These particulars are intended to give a fair description of the property, but the details are not guaranteed, nor do they form part of any contract. Applicants are advised to make Retail Area 17'10" x 17'0" (5.44m x 5.18m) appointments to view but the Agents cannot hold themselves responsible for any expenses incurred in inspecting properties Office / Storeroom 10'10" x 6'7" (3.30m x 2.00m) which may have been sold, let or withdrawn. -

Lincolnshire Local Flood Defence Committee Annual Report 1996/97

1aA' AiO Cf E n v ir o n m e n t ' » . « / Ag e n c y Lincolnshire Local Flood Defence Committee Annual Report 1996/97 LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL FLOOD DEFENCE COMMITTEE ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 THE FOLLOWING REPORT HAS BEEN PREPARED UNDER SECTION 12 OF THE WATER RESOURCES ACT 1991 Ron Linfield Front Cover Illustration Area Manager (Northern) Aerial View of Mablethorpe North End Showing the 1996/97 Kidding Scheme May 1997 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 136076 LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL FLOOD DEFENCE COMMITTEE ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Item No Page 1. Lincolnshire Local Flood Defence Committee Members 1 2. Officers Serving the Committee 3 3. Map of Catchment Area and Flood Defence Data 4 - 5 4. Staff Structure - Northern Area 6 5. Area Manager’s Introduction 7 6. Operations Report a) Capital Works 10 b) Maintenance Works 20 c) Rainfall, River Flows and Flooding and Flood Warning 22 7. Conservation and Flood Defence 30 8. Flood Defence and Operations Revenue Account 31 LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL FLOOD DEFENCE COMMITTEE R J EPTON Esq - Chairman Northolme Hall, Wainfleet, Skegness, Lincolnshire Appointed bv the Regional Flood Defence Committee R H TUNNARD Esq - Vice Chairman Witham Cottage, Boston West, Boston, Lincolnshire D C HOYES Esq The Old Vicarage, Stixwould, Lincoln R N HERRING Esq College Farm, Wrawby, Brigg, South Humberside P W PRIDGEON Esq Willow Farm, Bradshaws Lane, Hogsthorpe, Skegness Lincolnshire M CRICK Esq Lincolnshire Trust for Nature Conservation Banovallum House, Manor House Street, Homcastle Lincolnshire PROF. J S PETHICK - Director Cambs Coastal Research -

Adopted Central Lincolnshire Local Plan

CENTRAL LINCOLNSHIRE Local Plan Adopted April 2017 Central Lincolnshire | Local Plan - Adopted April 2017 Foreword Ensuring a flourishing future for Central Lincolnshire Central Lincolnshire is characterised by its diverse and enticing landscape. The magnificent city of Lincoln is embedded within our beautiful landscape and is surrounded by a network of picturesque towns and villages: these places, along with the social and economic opportunities in the area, make Central Lincolnshire a fantastic place to live, work and visit. But there is so much potential to make Central Lincolnshire an even better place. An even better place to live, with quality homes people can afford, easier access to shops, services and facilities, and new thriving communities, which are welcoming and safe. An even better place to work, where new facilities and infrastructure mean that businesses choose to expand or relocate here, bringing jobs and stimulating investment. An even better place to visit, a place where people choose to come to enjoy our nature, our history, our shops, our eateries and attractions, while at the same time significantly contributing to our rural and urban economies. A new Local Plan for Central Lincolnshire can do this. This is the adopted Local Plan for Central Lincolnshire. It was prepared with the benefit of your very helpful comments we received at various draft stages. Inside this adopted Local Plan are policies for the growth and regeneration of Central Lincolnshire over the next 20 years and beyond, including sites allocated for development and other areas designated for protection. The policies within the Local Plan will make sure that our settlements grow in the right way, ensure we have homes and employment where we need them, and ensure our new communities are sustainable, accessible and inclusive. -

Proposed Submission Consultation: Report on Key Issues Raised

Proposed Submission Consultation: Report on Key Issues Raised Technical Note: This Report forms part of the Statement as required to be produced under Regulation 22(C) of The Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012. Specifically, this Report covers part (v) of Regulation 22(C), which requires a statement to be produced which confirms that “if representations were made…the number of representations made and a summary of the main issues raised in those representations”. The requirements under parts (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv) of Regulation 22(C) are set out in separate Reports. June 2016 Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Summaries of key issues raised during the Proposed Submission consultation ....................... 2 General comments on Proposed Submission Local Plan ............................................................ 2 Foreword, Preface and Chapter 1 ............................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2 .................................................................................................................................... 4 Our Vision: A prosperous, stronger and sustainable Central Lincolnshire .................................... 4 LP1 A Presumption in Favour of Sustainable Development ......................................................... 5 LP2 The Spatial Strategy and Settlement Hierarchy ................................................................... -

Holton-Le-Moor Conservation Area Appraisal WLDC Holton Le Moor 8/5/08 9:52 Am Page 3

Conservation Holton-le-Moor Conservation Area Appraisal WLDC Holton Le Moor 8/5/08 9:52 am Page 3 Holton le Moor Conservation Area Appraisal 1 Introduction Holton le Moor is a rural estate village located 4 miles south west of Caistor, 22 miles north east of Lincoln and just to the west of the Lincolnshire Wolds Area of Outstanding Beauty. The village of Holton le Moor was first designated as a Conservation Area in January 1995. An appraisal was prepared to illustrate this interest and to define the character of the village and this document aims to update and reassess the appraisal of the conservation area in order to inform a future management plan. [1] View North along Market Rasen Road 2 WLDC Holton Le Moor 8/5/08 9:52 am Page 4 West Lindsey District Council 2 Summary of special interest conservation area, and suggests a linear settlement following the main route through Dating back to prehistory, present day the village.[1] The landscaped approach Holton le Moor predominantly reflects its from either the south or from the east via history as a planned estate village, Gatehouse Road prevents views of the constructed by philanthropic landowners buildings until you enter the village itself. with regard for both the social and In every case, the focus of attention are the economic life of this small rural community. tree lined roads leading through the village, The distinctive architectural character of the and as the church and manor house are village is enhanced by the building hidden from view, the visitor might miss the materials, fences, hedges trees and open 19th and early 20th century estate buildings spaces. -

The State of England's Chalk Streams

FUNDED WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM REPORT UK 2014 The State of England’s Chalk Streams This report has been written by Rose O’Neill and Kathy Hughes on behalf of WWF-UK with CONTENTS help and assistance from many of the people and organisations hard at work championing England’s chalk streams. In particular the authors would EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 like to thank Charles Rangeley-Wilson, Lawrence Talks, Sarah Smith, Mike Dobson, Colin Fenn, 8 Chris Mainstone, Chris Catling, Mike Acreman, FOREWORD Paul Quinn, David Bradley, Dave Tickner, Belinda by Charles Rangeley-Wilson Fletcher, Dominic Gogol, Conor Linsted, Caroline Juby, Allen Beechey, Haydon Bailey, Liz Lowe, INTRODUCTION 13 Bella Davies, David Cheek, Charlie Bell, Dave Stimpson, Ellie Powers, Mark Gallant, Meyrick THE STATE OF ENGLAND’S CHALK STREAMS 2014 19 Gough, Janina Gray, Ali Morse, Paul Jennings, Ken Caustin, David Le Neve Foster, Shaun Leonard, Ecological health of chalk streams 20 Alex Inman and Fran Southgate. This is a WWF- Protected chalk streams 25 UK report, however, and does not necessarily Aquifer health 26 reflect the views of each of the contributors. Chalk stream species 26 Since 2012, WWF-UK, Coca-Cola Great Britain and Pressures on chalk streams 31 Coca-Cola Enterprises have been working together Conclusions 42 to secure a thriving future for English rivers. The partnership has focused on improving the health A MANIFESTO FOR CHALK STREAMS 45 of two chalk streams directly linked to Coca-Cola operations: the Nar catchment in Norfolk (where AN INDEX OF ENGLISH CHALK STREAMS 55 some of the sugar beet used in Coca-Cola’s drinks is grown) and the Cray in South London, near 60 to Coca-Cola Enterprises’ Sidcup manufacturing GLOSSARY site. -

STRATEGIC REVIEW I of DEVELOPMENT and FLOOD RISK Ntv

STRATEGIC REVIEW I OF DEVELOPMENT AND FLOOD RISK nTv GRIMSBY AND ANCHOLME CATCHMENTS E n v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y River Humber • BARTON UPON HUMBER East Halton Beck IMMINGHAM BRIG River Freshney River Ancholme MARKET kSEN Environment Agency NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR ■ 2 STRATEGIC REVIEW OF DEVELOPMENT AND FLOOD RISK 0 ) | The Environment Agency MLIS ANGUA. REGION I* oo _iJ n u ki N ol nIj nUJ i The Environment Agency came into being on 1 LEGEND April 1996 as a result of the Environment Act Main River 1995. The flood defence powers, duties, and □ Catchment Boundary responsibilities of the now abolished National Fluvial Floodplain Rivers Authority transferred to the Agency. Tidal Floodplain In addition to flood defence, the responsibilities of the Agency include: the regulation of water quality and resources; fisheries, conservation, recreation and navigation issues; regulation of potentially polluting industrial processes; regulation of GRIMSBY premises which use, store, or dispose of radioactive material; and the prevention of pollution by licensing and controlling waste management sites, waste carriers and brokers. The Environment Agency's vision is of a better environment in England and Wales for present and future generations. The Agency will protect and improve the environment as a whole by effective regulation, by direct actions and by working with and influencing others. GRIMSBY AND ANCHOLME [CATCHMENTS ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 107618 GRIMSBY -

Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014

Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 West Lindsey DC SHLAA Map CL1253 Reference Site Address Sinclairs, Ropery Road, Gainsborough Site Area (ha) 3.03 Ward Gainsborough South West Parish Gainsborough Estimated Site 120 Capacity Site Description Brownfield site located within settlement boundary of Gainsborough The inclusion of this site or any other sites in this document does not represent a decision by the Central Lincolnshire authorities and does not provide the site with any kind of planning status. Page 1 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 Map CL1253 http://aurora.central- lincs.org.uk/map/Aurora.svc/run?script=%5cShared+Services%5cJPU%5cJPUJS.AuroraScri pt%24&nocache=1206308816&resize=always Page 2 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 West Lindsey DC SHLAA Map CL1289 Reference Site Address Main Road, Grayingham, Gainsborough, Lincs DN21 Site Area (ha) 8.05 Ward Hemswell Parish West Rasen Estimated Site 147 Capacity Site Description The inclusion of this site or any other sites in this document does not represent a decision by the Central Lincolnshire authorities and does not provide the site with any kind of planning status. Page 3 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 Map CL1289 http://aurora.central- lincs.org.uk/map/Aurora.svc/run?script=%5cShared+Services%5cJPU%5cJPUJS.AuroraScri pt%24&nocache=1206308816&resize=always -

Lincolnshire. [Kelly's

434 RA~D. LINCOLNSHIRE. [KELLY'S and turnips. The 8l'ea of Rand t~wnship is 989 acres ; Parish Clerk, William Clark. ll'ateable value, £r,796; the population in r8gr was in Le-tters through Wragby arrive by foot post at 8 a.m. & the township 67, and in the parish 128. are collected by postmen at 4.30 p.m. Wragby is the Fulnetby is a township in this parish, half a mile nearest ~ney order & telegoraph office south-west. The area. is r,r3r acres; of rateable value The children of Rand attend the school at Wragby & £725; the population in 1891 was 6r. those at Fulnetby that at Bolton RAND. Knapp Dinah ~rs. ), farmer FULNETBY. Laming William Allis, farmer Allis John, faTmer, Claybridge Spain Rev. Thomas Dixon, Rectory Paulger WLliam, farmer Musgrave Gothorp, frmr. Fulnetby hll HaTrison Alfred, farmer, Home farm Ward HaTry, farmer MIDDLE RASEN is a village, consisting of the the gift of the Bishop of Lincoln, who has one turn, and parishes of Middle R3lsen Drax and Middle Rasen Tup- the trustees of the late Emest Richard Chaxles Oust holme, r mile from Market Rasen on the road ro Gains- esq. who have two turns, and held since r879 by the Rev. borough and on the river Rase, in the East Linrusey Arthur William Tryon M.A. of Downing College, Cam division of the county, south division of Walshcroft bridge. There axe Wesleyan, Primitive Methodist and wapentake, parts of Lindsey, Ca·istor union, petty ses- Reformed Wesleyan chapels. Frederic Sneath esq. who sional division and county court district of Market Rasen, is lord of the manor, and Pereira.