Oil, Gas & Energy Law Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

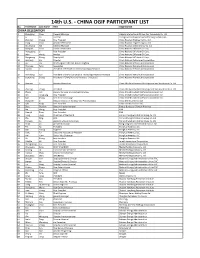

14TH OGIF Participant List.Xlsx

14th U.S. ‐ CHINA OGIF PARTICIPANT LIST No. First Name Last Name Title Organization CHINA DELEGATION 1 Zhangxing Chen General Manager Calgary International Oil and Gas Technology Co. Ltd 2 Li He Director Cheng Du Development and Reforming Commission 3 Zhaohui Cheng Vice President China Huadian Engineering Co. Ltd 4 Yong Zhao Assistant President China Huadian Engineering Co. Ltd 5 Chunwang Xie General Manager China Huadian Green Energy Co. Ltd 6 Xiaojuan Chen Liason Coordinator China National Offshore Oil Corp. 7 Rongguang Li Vice President China National Offshore Oil Corp. 8 Wen Wang Analyst China National Offshore Oil Corp. 9 Rongwang Zhang Deputy GM China National Offshore Oil Corp. 10 Weijiang Liu Director China National Petroleum Cooperation 11 Bo Cai Chief Engineer of CNPC RIPED‐Langfang China National Petroleum Corporation 12 Chenyue Feng researcher China National Petroleum Corporation 13 Shaolin Li President of PetroChina International (America) Inc. China National Petroleum Corporation 14 Xiansheng Sun President of CNPC Economics & Technology Research Institute China National Petroleum Corporation 15 Guozheng Zhang President of CNPC Research Institute(Houston) China National Petroleum Corporation 16 Xiaquan Li Assistant President China Shenhua Overseas Development and Investment Co. Ltd 17 Zhiming Zhang President China Shenhua Overseas Development and Investment Co. Ltd 18 Zhang Jian deputy manager of unconventional gas China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 19 Wu Jianguang Vice President China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 20 Jian Zhang Vice General Manager China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 21 Dongmei Li Deputy Director of Strategy and Planning Dept. China Zhenhua Oil Co. Ltd 22 Qifa Kang Vice President China Zhenhua Oil Co. -

Master's Thesis

Faculty of Science and Technology MASTER’S THESIS Study Program / Specialization: Fall semester, 2012 Offshore Technology / Industrial Restricted access Economics Author: Sun, Gang (Signature author) Faculty Supervisor: Professor Jayantha P. Liyanage, PhD Title of Thesis: Choosing Appropriate Commercial Models for Overseas Business: A case study of a Chinese oil service provider towards Internationalization Credits (ECTS): 30 ETCS Key Words: Commercial Models; Internationalization; Pages: 48 Spin off; China, June 2014 Liability; Restructure; Benchmark. Acknowledgements I want to express my greatest gratitude to my supervisor Professor J.P Liyanage for his extraordinary patience and wisdom guiding me through this process. Writing the thesis was not easy, but rather challenging and time-consuming, with the help of his feedback I could find the interesting topics and look at my work more critically and improve it. I would like to thank Professor Tore Markeset, Professor O.T Gudmestad, and Mr. Frode Leidland for their kind instructions during my study in Norway. I am very thankful to Mr. Chen, Zongjiang, as the Director of PT COSL INDO, who has offered me a lot of newest updates relevant to the restructuring of PT COSL INDO. Besides, Mr. Wang, Tongyou and Mr. Wang, Jin as my Colleagues, and Mr. Peng, Guicang as my ex-coworker, have given me a hand on how bridging the gap between me and the required academic level. I would also like to take the chance to express my appreciation to Mr. Li, Yong, Mr. Zi, Silong, Mr. Li, Zhi and Mr. Zhang, Xingyun who on behalf of the company COSL to sponsor my graduate study in University of Stavanger, without their good faith and deeds for the youth of their company, I could not finish the study in good wellbeing. -

National Oil Companies: Business Models, Challenges, and Emerging Trends

Corporate Ownership & Control / Volume 11, Issue 1, 2013, Continued - 8 NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES: BUSINESS MODELS, CHALLENGES, AND EMERGING TRENDS Saud M. Al-Fattah* Abstract This paper provides an assessment and a review of the national oil companies' (NOCs) business models, challenges and opportunities, their strategies and emerging trends. The role of the national oil company (NOC) continues to evolve as the global energy landscape changes to reflect variations in demand, discovery of new ultra-deep water oil deposits, and national and geopolitical developments. NOCs, traditionally viewed as the custodians of their country's natural resources, have generally owned and managed the complete national oil and gas supply chain from upstream to downstream activities. In recent years, NOCs have emerged not only as joint venture partners globally with the major oil companies, but increasingly as competitors to the International Oil Companies (IOCs). Many NOCs are now more active in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), thereby increasing the number of NOCs seeking international upstream and downstream acquisition and asset targets. Keywords: National Oil Companies, Petroleum, Business and Operating Models * Saudi Aramco, and King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) E-mail: [email protected] Introduction historically have mainly operated in their home countries, although the evolving trend is that they are National oil companies (NOCs) are defined as those going international. Examples of NOCs include Saudi oil companies that have significant shares owned by Aramco (the largest integrated oil and gas company in their parent government, and whose missions are to the world), Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (KPC), work toward the interest of their country. -

Sinochem International 2015 Corporate Social Responsibility Report

Sinochem International 2015 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Sinochem International Plaza, NO.233 North Changqing Rd., Pudong New Area, Shanghai 200126, P.R.China Tel: 86-21-31768000 Fax: 86-21-31769199 www.sinochemintl.com This report is printed on the recycled paper. ABOUT THIS REPORT This is the fifth Sustainable Development Report of Sinochem International Table of Contents Corporation. The previous four reports were issued in 2012, 2013 ,2014 and 2015. Sinochem International Corporation also published Corporate Social Responsibility Reports for 12 years in a row from 2005. 01 05 15 19 REPORT PERIOD This report covers activities of Sinochem International Corporation between 1st Chairman’s Environmental Shareholders January and 31st December 2015. In some instances content may reflect activities Employee and data from previous years. Address Protection and Benefits and Creditors REPORT PUBLICATION CYCLE Production Safety • Fair Employment • Stable Development This is an annual report. • Strengthening Environmental to Create Value for REPORT SCOPE Management and Improving • Protection of Rights Shareholders This report includes Sinochem International Corporation and its subsidiaries. Environmental Performance and Interests • Risk Prevention to REPORT REFERENCE • Strengthening Front-Line • Occupational Health The report follows the guidance of the Guidelines for Key State-owned Enterprises Effectively Protect the to Fulfill Corporate Social Responsibility, the Inform of Strengthen the CSR Management and Improving Interests of Creditors -

China and IMO 2020

December 2019 China and IMO 2020 OIES PAPER: CE1 Michal Meidan The contents of this paper are the author’s sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2019 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN : 978-1-78467-154-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26889/9781784671549 2 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Background: IMO 2020 .................................................................................................................. 3 II. China: Tough government policies to tackle shipping emissions… ....................................... 5 III. ...but a relatively muted response from refiners ..................................................................... 7 a. A tale of two bunker markets ....................................................................................................... -

Chinacoalchem

ChinaCoalChem Monthly Report Issue May. 2019 Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved. ChinaCoalChem Issue May. 2019 Table of Contents Insight China ................................................................................................................... 4 To analyze the competitive advantages of various material routes for fuel ethanol from six dimensions .............................................................................................................. 4 Could fuel ethanol meet the demand of 10MT in 2020? 6MTA total capacity is closely promoted ....................................................................................................................... 6 Development of China's polybutene industry ............................................................... 7 Policies & Markets ......................................................................................................... 9 Comprehensive Analysis of the Latest Policy Trends in Fuel Ethanol and Ethanol Gasoline ........................................................................................................................ 9 Companies & Projects ................................................................................................... 9 Baofeng Energy Succeeded in SEC A-Stock Listing ................................................... 9 BG Ordos Started Field Construction of 4bnm3/a SNG Project ................................ 10 Datang Duolun Project Created New Monthly Methanol Output Record in Apr ........ 10 Danhua to Acquire & -

Chinese Refining Industry Under Crude Oil Import Right Liberalisation

2015/11/2 IEEJ:November 2015, All Rights Reserved. CNPC Chinese Refining Industry Under Crude Oil Import Right Liberalisation CNPC Economics and Technology Research Institute 2015.11.3 Outlines 1.Status of Chinese Refining Industry 2.Challenges to Chinese Refining Industry 3.Prospects of Chinese Refining Industry Development CNPC ETRI | Page 2 61 1 2015/11/2 IEEJ:November 2015, All Rights Reserved. 1. China's refining capacity has been developing rapidly There are 220 refineries in China,and the total crude processing capacity up to 702 million tons/year. It accounts for 14.5% of the world by the end of September 2015. The average scale of the refinery is 3.2 million tons/year, compared with average 7.18 million tons/ year of the world, there are still a large gap. CNPC has 26 refineries which average scale is 7.46 million tons/year. Sinopec has 35 refineries which average scale is 7.71 million tons/year. Crude Processing Capacity of China Refining Capacity of Chinese Enterprise (100 million tons/ year) (10000 tons/year) 8 10-20million above 20 7.02 tons/year, 22 million 6.63 7 6.29 tons/year, 3 5.94 6 5.68 5.17 5 4.54 4.02 4 3.57 3.153.25 5-10million 2.81 2.9 3.04 below 2 3 tons/year, 50 million 2 tons/year, 98 The refining 1 capacity in the 2-5million graph refers to 0 tons/year, 47 single refinery CNPC ETRI | Page 3 Data Source: CNPC ETRI 2. China's oil refining industry participant is diversified Central State-owned enterprises: CNPC and Sinopec play the leading role. -

Negativliste. Fossil Energi

Bilag 6. Negativliste. Fossil energi Maj 2017 Læsevejledning til negativlisten: Moderselskab / øverste ejer vises med fed skrift til venstre. Med almindelig tekst, indrykket, er de underliggende selskaber, der udsteder aktier og erhvervsobligationer. Det er de underliggende, udstedende selskaber, der er omfattet af negativlisten. Rækkeetiketter Acergy SA SUBSEA 7 Inc Subsea 7 SA Adani Enterprises Ltd Adani Enterprises Ltd Adani Power Ltd Adani Power Ltd Adaro Energy Tbk PT Adaro Energy Tbk PT Adaro Indonesia PT Alam Tri Abadi PT Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd Africa Oil Corp Africa Oil Corp Alpha Natural Resources Inc Alex Energy Inc Alliance Coal Corp Alpha Appalachia Holdings Inc Alpha Appalachia Services Inc Alpha Natural Resource Inc/Old Alpha Natural Resources Inc Alpha Natural Resources LLC Alpha Natural Resources LLC / Alpha Natural Resources Capital Corp Alpha NR Holding Inc Aracoma Coal Co Inc AT Massey Coal Co Inc Bandmill Coal Corp Bandytown Coal Co Belfry Coal Corp Belle Coal Co Inc Ben Creek Coal Co Big Bear Mining Co Big Laurel Mining Corp Black King Mine Development Co Black Mountain Resources LLC Bluff Spur Coal Corp Boone Energy Co Bull Mountain Mining Corp Central Penn Energy Co Inc Central West Virginia Energy Co Clear Fork Coal Co CoalSolv LLC Cobra Natural Resources LLC Crystal Fuels Co Cumberland Resources Corp Dehue Coal Co Delbarton Mining Co Douglas Pocahontas Coal Corp Duchess Coal Co Duncan Fork Coal Co Eagle Energy Inc/US Elk Run Coal Co Inc Exeter Coal Corp Foglesong Energy Co Foundation Coal -

The Annual World Petroleum & Petrochemical Event

The Annual World Petroleum & Petrochemical Event The largest private exhibition company in China Top 10 Exhibition Companies in China Top 10 Influential Companies in China Exhibition Industry Vice-president Unit of China Convention and Exhibition Society Vice-chairman Unit of Exhibition Committee of China Chamber of International Commerce Zhenwei Exhibition, founded in 2000 and listed on New Three Board market on November 24, 2015 (innovation-layer enterprise, The significantly influential exhibitions held by Zhenwei Exhibition stock code: 834316), is the largest private exhibition company in China, one of the earliest Chinese members of UFI (Union of China International Petroleum & Petrochemical Technology and Equipment Exhibition (cippe) International Fairs), and vice-president unit of China Convention and Exhibition Society. Zhenwei Exhibition has developed into China (Tianjin) International Industrial Expo (CIEX) the industry-leading comprehensive service provider of global exhibition focusing on convention and exhibition and integrating exhibition & convention, digital information and e-commerce. Tianjin International Robot Exhibition (CIRE) Shanghai International New Energy Vehicle Industry Expo (NEVE) Headquartered in Binhai New Area, Tianjin and owns Tianjin Zhenwei, Beijing Zhenwei, Guangzhou Zhenwei, Xinjiang Zhenwei, Xi'an Zhenwei, Chengdu Zhenwei and Beijing Zhongzhuang Runda Exhibition. In 2015, Zhenwei Exihibition and Xinjiang China International Electric Vehicle Supply Equipments Fair (EVSE) International Expo Administration -

Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas

Canadian Energy Research Institute Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas Jon Rozhon March 2012 Relevant • Independent • Objective Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas 1 Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands There has been a steady flow of foreign investment into the oil sands industry over the past decade in terms of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. Out of a total CDN$61.5 billion in M&A’s, approximately half – or CDN$30.3 billion – involved foreign companies taking an ownership stake. These funds were invested in in situ projects, integrated projects, and land leases. As indicated in Figure 1, US and Chinese companies made the most concerted efforts to increase their profile in the oil sands, investing 2/3 of all foreign capital. The US and China both invested in a total of seven different projects. The French company, Total SA, has also spread its capital around several projects (four in total) while Royal Dutch Shell (UK), Statoil (Norway), and PTT (Thailand) each opted to take large positions in one project each. Table 1 provides a list of all foreign investments in the oil sands since 2004. Figure 1: Total Oil Sands Foreign Investment since 2003, Country of Origin Korea 1% Thailand Norway 6% UK 7% 2% US France 33% 18% China 33% Source: Canoils. Foreign Investment in the Oil Sands and British Columbia Shale Gas 2 Table 1: Oil Sands Foreign Investment Deals Year Country Acquirer Brief Description Total Acquisition Cost (000) 2012 China PetroChina 40% interest in MacKay River 680,000 project from AOSC 2011 China China National Offshore Acquisition of OPTI Canada 1,906,461 Oil Corporation 2010 France Total SA Alliance with Suncor. -

2013 Financial and Operating Review

Financial & Operating Review 2 013 Financial & Operating Summary 1 Delivering Profitable Growth 3 Global Operations 14 Upstream 16 Downstream 58 Chemical 72 Financial Information 82 Frequently Used Terms 90 Index 94 General Information 95 COVER PHOTO: Liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced at our joint ventures with Qatar Petroleum is transported to global markets at constant temperature and pressure by dedicated carriers designed and built to meet the most rigorous safety standards. Statements of future events or conditions in this report, including projections, targets, expectations, estimates, and business plans, are forward-looking statements. Actual future results, including demand growth and energy mix; capacity growth; the impact of new technologies; capital expenditures; project plans, dates, costs, and capacities; resource additions, production rates, and resource recoveries; efficiency gains; cost savings; product sales; and financial results could differ materially due to, for example, changes in oil and gas prices or other market conditions affecting the oil and gas industry; reservoir performance; timely completion of development projects; war and other political or security disturbances; changes in law or government regulation; the actions of competitors and customers; unexpected technological developments; general economic conditions, including the occurrence and duration of economic recessions; the outcome of commercial negotiations; unforeseen technical difficulties; unanticipated operational disruptions; and other factors discussed in this report and in Item 1A of ExxonMobil’s most recent Form 10-K. Definitions of certain financial and operating measures and other terms used in this report are contained in the section titled “Frequently Used Terms” on pages 90 through 93. In the case of financial measures, the definitions also include information required by SEC Regulation G. -

A Comparison of Natural Gas Pricing Mechanisms of the End-User Markets in USA, Japan, Australia and China

A Comparison of Natural Gas Pricing Mechanisms of the end-user markets In USA, Japan, Australia and China China-Australia Natural Gas Technology Partnership Fund 2013 Leadership Imperative Li Yuying, SHDRC Li Jinsong, CNOOC Gas and Power Group Yu Zhou, Guangdong Dapeng LNG Co Ltd. Wang Zhang, Guangdong Dapeng LNG Co Ltd. August 6th, 2013 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................6 Executive Summery .........................................................................................................7 01 Introduction .......................................................................................................................8 1.1 Background ...........................................................................................................8 1.2 Definition of Pricing Mechanism ...........................................................................9 1.3 Overall Purpose of this Project ...............................................................................9 1.4 Proposed Outcome ............................................................................................... 10 1.5 Structure of the Report ......................................................................................... 10 02 Gas Market & Pricing Mechanism in USA ...................................................................... 10 2.1 USA Natural Gas Demand ..................................................................................