War and Imprisonment: a Discourse Analysis Exploring the Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Police Militarization

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 Citizens, Suspects, and Enemies: Examining Police Militarization Milton C. Regan Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2346 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3772930 Texas National Security Review, Winter 2020/2021. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Citizens, Suspects, and Enemies: Examining Police Militarization Mitt Regan Abstract Concern about the increasing militarization of police has grown in recent years. Much of this concern focuses on the material aspects of militarization: the greater use of military equipment and tactics by police officers. While this development deserves attention, a subtler form of militarization operates on the cultural level. Here, police adopt an adversarial stance toward minority communities, whose members are regarded as presumptive objects of suspicion. The combination of material and cultural militarization in turn has a potential symbolic dimension. It can communicate that members of minority communities are threats to society, just as military enemies are threats to the United States. This conception of racial and ethnic minorities treats them as outside the social contract rather than as fellow citizens. It also conceives of the role of police and the military as comparable, thus blurring in a disturbing way the distinction between law enforcement and national security operations. -

A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia

sustainability Article A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia Yeohyun Yoon 1 and Kyoung Cheon Cha 2,* 1 School of Hotel and Tourism Management, Youngsan University, Busan 48015, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Business Administration, Dong-A University, Busan 49236, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 29 September 2020; Published: 30 September 2020 Abstract: Although the cruise sector is considered an ‘unreplaceable’ form of tourism, with the cruise industry recording steady growth over the years, there is a lack of research and analysis on cruise ships themselves. Accordingly, this study sought to determine whether service quality differences among ships operating in the Asian market could suggest broader implications for the sustainability of the cruise industry. We chose the SERVQUAL framework for the analysis; we also employed the multiple case study method and topic synthesis to compare the service quality of three ships. Of the ships investigated—the Costa Victoria, Diamond Princess, and Superstar Virgo—the Diamond Princess had the highest service quality. Based on the results, we outlined suggestions for improving the quality of cruise services, including introducing the latest large ships and high-tech facilities, complying with the departure and arrival times of sailing schedules, improving the ratio of crew members per passenger, establishing a cruise personnel training system, and expanding membership program operations. Keywords: cruise; service quality; SERVQUAL; onboard attributes 1. Introduction Cruise tourism is one of the fastest growing tourism segments, and it has undergone significant transformation, especially in the last few decades [1,2]. -

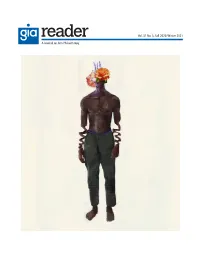

GIA Reader, Volume 31, Number 3 (Winter 2021)

Vol. 31 No. 3, Fall 2020/Winter 2021 A Journal on Arts Philanthropy 2 Grantmakers in the Arts Reader: Volume 31, No. 3, Fall 2020/Winter 2021 RESEARCH Foundation Grants to Arts and Culture, 2018: A One-Year Snapshot ...................................................5 Reina Mukai Public Funding for the Arts 2020 ............................................................................................................12 Ryan Stubbs and Patricia Mullaney-Loss READINGS Centered. Elevated. Celebrated. Well Resourced. Welcome to Nonprofit Wakanda. .........................16 David McGoy DEI Work is Governance Work ................................................................................................................18 Jim Canales and Barbara Hostetter The Equity Builder Loan Program: Looking Toward Autonomy and Freedom from the Crisis Cycle ................................................................................................................................20 Quinton Skinner Equity. Equity. Equity. ..............................................................................................................................25 Shaunda McDill Arts Funders Should Build Stability and Resilience for Black Artists and Cultural Communities .......................................................................................................................26 Tracey Knuckles A Question of (dis)Trust: Lessons When Your Institution Gets Taken Down ....................................27 Anida Yoeu Ali and Shin Yu Pai San Diego/Tijuana: -

Vaccines from Bahrain, Which Are Under Probe, Are Chinese, Officials

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXIX No. 29 | 12 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 34.4 C 2.5 C Friday, March 19, 2021 | 06-12-2077 Nepalgunj Jumla Vaccines from Bahrain, which are under probe, are Chinese, officials say Nepal’s drug regulator says it is consulting with foreign and health ministries, as the issue is not just technical but also concerns bilateral ties and diplomacy. ARJUN POUDEL Sinopharm’s BBIBP-CorV but not to KATHMANDU, MARCH 18 Sinovac’s CoronaVac. Nepal, however, has not rolled out A report on an investigation into Sinopharm vaccines yet. The Oxford- how 2,000 doses of Covid-19 vaccine AstraZeneca vaccine was the first to were brought to Nepal by a Bahraini get emergency use authorisation in prince was to be submitted on Nepal. The vaccine, manufactured by Thursday evening. the Serum Institute of India under the But officials on Thursday afternoon brand name of Covishield, is current- said that the vaccines were Chinese, ly being used in Nepal. not AstraZeneca as claimed before. Sheikh Mohamed Hamad Mohamed At least two officials at the Health al-Khalifa, the Bahraini prince, and Ministry, who did not wish to be his team landed in Kathmandu on named, said that the vaccines from Monday on an Everest mission. Bahrain are Chinese and developed The Nepali embassy in Bahrain on by Sinovac Biotech, for which Nepal Monday said in a statement that the has not granted emergency use prince’s team would be carrying 2,000 authorisation. -

On the Front Line? Metaphors of War and Violence in Academic Libraries

On the Front Line? Metaphors of War and Violence in Academic Libraries Melanie Boyd University of Calgary Ozouf Senamin Amedegnato University of Calgary ABSTRACT Is there room for war metaphor in academic libraries? Is there a good, or justifiable, reason for its use? In this paper, we argue the answer to these questions is no. The paper will discuss the nature of metaphor in general, the effects of its use, and why those effects matter. Grounded in this discussion, it will consider and analyze the use of war metaphor, specifically in the academic library world. Finally, it will offer suggestions for how, through individual and collective effort, the metaphor of war might be purged from the academic library lexicon. Keywords: academic libraries · language · violence · war metaphor RÉSUMÉ La métaphore guerrière a-t-elle une place dans les bibliothèques universitaires? A-t-on une bonne raison d’y recourir? Cette contribution répond aux deux questions par la négative. Le texte définira dans un premier temps la métaphore et exposera son fonctionnement ainsi que ses manifestations. Suivra ensuite une analyse de l’usage de la métaphore guerrière dans le contexte précis des bibliothèques universitaires. Enfin, les auteurs expliqueront comment, à travers un effort individuel et collectif, les interactions bibliothécaires peuvent être expurgées de leurs contenus belliqueux. Mots-clés : bibliothèques universitaires · langage · métaphore guerrière · violence A dozen academic librarians sit round a table discussing how to trim the budget, for which the outlook is dire. Some librarians offer suggestions; others challenge them in return. After an hour, without consensus reached, the chairperson says: At some point we’ll just have to pull the trigger. -

Section 2: the China Model: Return of the Middle Kingdom

SECTION 2: THE CHINA MODEL: RETURN OF THE MIDDLE KINGDOM Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeks to revise the inter- national order to be more amenable to its own interests and authoritarian governance system. It desires for other countries not only to acquiesce to its prerogatives but also to acknowledge what it perceives as China’s rightful place at the top of a new hierarchical world order. • The CCP’s ambitions for global preeminence have been con- sistent throughout its existence: every CCP leader since Mao Zedong has proclaimed the Party would ultimately prove the superiority of its Marxist-Leninist system over the rest of the world. Under General Secretary of the CCP Xi Jinping, the Chi- nese government has become more aggressive in pursuing its interests and promoting its model internationally. • The CCP aims to establish an international system in which Beijing can freely influence the behavior and access the mar- kets of other countries while constraining the ability of others to influence its behavior or access markets it controls. The “com- munity of common human destiny,” the CCP’s proposed alter- native global governance system, is explicitly based on histor- ical Chinese traditions and presumes Beijing and the illiberal norms and institutions it favors should be the primary forces guiding globalization. • The CCP has attempted to use the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to promote itself as a responsible and benevolent global leader and to prove that its model of governance is su- perior to liberal democracy. Thus far, it appears Beijing has not changed many minds, if any. -

COVID-19: Emerging Trials and Treatments

Emerging Therapies for CoVID-19 CAPT Ryan Schupbach, PharmD, BCPS, CACP Vice Chair, IHS National Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee IHS COVID-19 TeleECHO Session September 17, 2020 OBJECTIVES • Identify evidence-based therapies for treatment of CoVID-19 SARS-CoV2 structure • Review clinical trial characteristics of Spike (S) emerging CoVID-19 therapies Envelope (E) Genome RNA Nucleocapsid (N) • Examine the availability and staging of Membrane (M) leading CoVID-19 vaccines Adapted from Jin Y et al. Viruses. 2020 March 7 2 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Nothing to disclose • I have no financial relationships with commercial entities producing healthcare related products and/or services. 3 Potential Therapies: CoVID-19 • >1000 compounds theorized with potential against COVID-19 • 27 FDA-approved drugs initially identified as candidates (repurposing) • Over 20,000 safety-tested (unmarketed) compounds in FDA Database • 400,000 natural products available; many using supercomputers to identify computational matches (pharmacophore analysis) • Over 1200 clinical trials registered globally since March • Analysis showed 38% of trials had planned enrollment of <100 patients 1. Krogan, N. How COVID-19 Drug Hunters Spot Virus-Fighting Compounds. Scientific American. March 20, 2020. 2. US Food and Drug Administration. FACT SHEET. www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-basics/fact-sheet-fda-glance 3. Stat-AppliedXL analysis. Data from ClinicalTrials.gov 4 4. Steele Ji. Medical Press. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-06-lab-naturally-compounds-potential-covid-.html. June 19, 2020 5 Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J (2020) Race to find COVID-19 treatments accelerates. Science (New York, NY) 367:1412–1413 6 FasterCures. The Milken Institute. © 2020 Milken Institute and First Person. -

Chiraq: One Person's Metaphor Is Another's Reality

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE January 2015 Chiraq: One person's metaphor is another's reality Jacoby Cochran Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cochran, Jacoby, "Chiraq: One person's metaphor is another's reality" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 356. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/356 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This Master’s Thesis explores the deployment and appropriation of the war metaphor as it relates to criminal justice policy in the United States from 1930 forward, paying close attention to the 1980s and 2010s. More specifically, this thesis centers on the city of Chicago to analyze the use of the war metaphor throughout the city’s history, from earlier invocations by Mayors to present- day, local appropriations in the form of the metaphor Chiraq, which blends Chicago and Iraq as a statement to the conditions of some of Chicago’s most resource deprived neighborhoods. Using Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980) Conceptual Metaphor Theory I will outline how the war metaphor has been studied in rhetoric and utilized in Presidential, Mayoral, and media discourses in chapter one. In chapter two, I will turn my attention to fragments organized around the metaphorical term Chiraq and apply CMT to highlight how the war metaphor has become a central component of daily language in Chicago’s most volatile neighborhoods. -

Higher Education in Wartime and the Development of National Defense

The First Line of Defense: Higher Education in Wartime and the Development of National Defense Education, 1939-1959 Dana Adrienne Ponte a dissertation to be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON 2016 Reading Committee: Maresi Nerad, Chair Nancy Beadie Bill Zumeta Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Educational Leadership & Policy Studies ©Copyright 2016 Dana Adrienne Ponte Abstract This study posits that the National Defense Education Act of 1958 (NDEA) represented the culmination of nearly a century-long process through which education was linked to national defense in periods of wartime, and later retained a strategic utility for defense purposes in times of peace. That a defense rationale for federal support of public higher education achieved a staying power that outlasted moments of temporary strategic necessity is due in large part to the efforts of individuals in the education and policymaking communities who were able to envision and promote a lasting, expansive definition of education for national defense – one that would effectively marshal federal funding for decades to come. In the latter half of the 20th century, it was precisely this definition that provided the rationale for further federal forays into public education in the United States, accumulating into a level of involvement that now feels commonplace. Despite its present predominance, however, this relationship was by no means a foregone conclusion in the early decades of the 20th century. The United States has historically been defined by its constitutional separation of federal and state powers, notably made manifest in a traditional emphasis on state control over public education. -

How Risk Theory Gave Rise to Global Police Militarization

Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 12 Winter 2016 Global Insecurity: How Risk Theory Gave Rise to Global Police Militarization Nicholas S. Bolduc Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Bolduc, Nicholas S. (2016) "Global Insecurity: How Risk Theory Gave Rise to Global Police Militarization," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol23/iss1/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Global Insecurity: How Risk Theory Gave Rise to Global Police Militarization NICHOLAS S. BOLDUC* ABSTRACT Today, across the globe, police agencies are militarizing to confront modern-day threats. This gradual shift towards militarized policing stems from the concept of risk-risk has driven nations to amend their laws so that their law enforcement agencies may militarize to meet whatever risk they face. In the United States, the gradual shift towards militarizedpolice occurred after the crippling of the Posse Comitatus Act in the face of the developing 'War on Drugs" However, America is a late development in this trend; the majority of the Western world militarized themselves through the concept of 'gendarmes", while the Chinese militarized their police immediately after the Communist Revolution. -

Metaphorizing Dialogue to Enact a Flow Culture Transcending Divisiveness by Systematic Embodiment of Metaphor in Discourse -- /

Alternative view of segmented documents via Kairos 6 May 2019 | Draft Metaphorizing Dialogue to Enact a Flow Culture Transcending divisiveness by systematic embodiment of metaphor in discourse -- / -- Introduction Metaphorizing -- beyond one-off usage Sustaining dialogue through metaphor? Indicative precedents of metaphorizing skills Discourse and debate reframed as cognitive combat through metaphor? Integrity of metaphorizing framed by complementarity between alternatives Imagining a relevant philosophers' game -- and beyond Requisite metaphoric "circumlocution" avoiding disruptive disagreement Sustainable discourse framed metaphorically as "orbiting" Metaphorizing as artful indulgence in misplaced concreteness? Re-imagining: metaphorizing, metamorphizing and cognitive shapeshifting Sustainable discourse: longest conflict versus longest conversation? References Introduction There is no difficulty in recognizing the extent to which discourse has become problematic, whether in national assemblies, parliaments, or the media (social media or otherwise). The current scene has been described as poisonously divisive. Each faction is adamant that the facts and principles it presents are beyond question. Each is necessarily right, with any in disagreement being by definition wrong. Discourse between nations, between religions, between political parties, and between disciplines currently offers little hope for a more fruitful modality. Curiously efforts towards transcending this situation -- if they are more than tokenistic -- seem to be readily entrapped by the same dynamic. Each is necessarily right or better, with others essentially misguided, misinformed or behind the times. The following is an exploration of a distinctive mode which does not rely on facts and truth as commonly understood, or on the deprecation of fake news and pretence. The focus is not on being right or wrong or the attribution of blame. -

Star Cruises Limited

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Genting Hong Kong Limited (Continued into Bermuda with limited liability) (Stock Code: 678) ANNOUNCEMENT (1) AUDITED RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020; AND (2) GRANT OF WAIVER FROM STRICT COMPLIANCE WITH RULE 13.46(2)(a) OF THE LISTING RULES Reference is made to the announcement of Genting Hong Kong Limited (the “Company”) dated 31 March 2021 in relation to the unaudited annual results of the Company and its subsidiaries (the “Group”) for the year ended 31 December 2020 (the “Unaudited 2020 Results Announcement”). As stated in the Unaudited 2020 Results Announcement, the auditor has notified the Company that more time is required to complete the audit and therefore the unaudited annual results of the Group for the year ended 31 December 2020 contained therein have not been agreed with the Company’s auditor as required under Rule 13.49(2) of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. The Board of Directors of the Company is pleased to announce that the auditing process for the annual results of the Group for the year ended 31 December 2020 has been completed. The Group’s audited consolidated statement of comprehensive income and consolidated statement of financial position in this announcement is consistent with the unaudited annual results of the Group contained in the Unaudited 2020 Results Announcement.