A Comparative Study of the Digital Transition of the Print Media in Nigeria and South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restoration of Tulbagh As Cultural Signifier

BETWEEN MEMORY AND HISTORY: THE RESTORATION OF TULBAGH AS CULTURAL SIGNIFIER Town Cape of A 60-creditUniversity dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in the Conservation of the Built Environment. Jayson Augustyn-Clark (CLRJAS001) University of Cape Town / June 2017 Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment: School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ‘A measure of civilization’ Let us always remember that our historical buildings are not only big tourist attractions… more than just tradition…these buildings are a visible, tangible history. These buildings are an important indication of our level of civilisation and a convincing proof for a judgmental critical world - that for more than 300 years a structured and proper Western civilisation has flourished and exist here at the southern point of Africa. The visible tracks of our cultural heritage are our historic buildings…they are undoubtedly the deeds to the land we love and which God in his mercy gave to us. 1 2 Fig.1. Front cover – The reconstructed splendour of Church Street boasts seven gabled houses in a row along its western side. The author’s house (House 24, Tulbagh Country Guest House) is behind the tree (photo by Norman Collins). -

Table of Contents

South African tabloid newspapers’ representation of black celebrities: A social constructionism perspective Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Journalism) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Josh Ogada September 2009 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: (Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela) Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people: . My supervisor, Josh Ogada, for his expert and invaluable guidance throughout the course of my studies. Professor Alet Kruger for helping me with the translations. The University of South Africa for providing me unrestricted access to their library facilities. My parents, John and Paulina Matsebatlela, for their unwavering support and constant encouragement. My wife, Molebogeng, for her patience, motivation and support. 2 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this study to my late Uncles, Rangwane M’phalaborwa ‘Mamodila Selemantwa’ Matsebatlela and Malome Thomas Mahlo. Though their life journeys have ended, they will forever remain etched in our memories. May their souls rest in peace. 3 ABSTRACT This study examines how positively or negatively as well as how subjectively or objectively the South African tabloid newspapers represent black celebrities. This examination was primarily conducted by using the content analysis research technique. The researcher selected a total of 85 newspapers spread across four different South African daily and weekend tabloid newspapers that were published during the period February to September 2008. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis of Punch and Daily

TUG OF WAR: A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF PUNCH AND DAILY TRUST NEWSPAPERS’ COVERAGE OF POLIO ERADICATION IN NIGERIA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies of RHODES UNIVERSITY By AYANFEOLUWA OLUTOSIN OYEWO Supervisor: Danika Marquis September 2014 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the world’s greatest parents: Dr and Pharm, O. O. Oyewo. No amount of words can effectively capture the depth of my gratitude to you both. Thank you for the sacrifices you made, for believing in me, and for the endless prayers. I love you, and God bless you. I also dedicate this thesis in honour of my late grandfather, Mr. Adebayo Adio Oyedemi. Your exemplary life was and is an inspiration to me. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, my gratitude goes to God for granting me the grace and speed needed to complete this study. I am grateful to my supervisor, Danika Marquis, for her patience, kindness and thoroughness during the research process. I am also indebted to Professor Jeanne Prinsloo for introducing me to the world of Critical Discourse Analysis. My gratitude also goes to great friends and colleagues; Pauline Atim, Dayo Fashina, Khanyile Mlosthwa, Lauren Hutcheson, Similoluwa Olusola, Carly Hosford-Israel, Mathew Nyaungwa, and Oluwasegun Owa, for their intellectual, and moral support. I would also like to thank my grandmothers, Deaconess C. M. Oyedemi, and Deaconess J. A. Oyewo, for their words of encouragement and prayers. To my siblings (Obaloluwa, Ooreoluwa and Ireoluwa), cousins, uncles, and aunts, thank you for your overwhelming expressions of love. -

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

Blurred Lines

BLURRED LINES: HOW SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM HAS CHANGED WITH A NEW DEMOCRACY AND EVOLVING COMMUNICATION TOOLS Zoe Schaver The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism Advised by: __________________________ Chris Roush __________________________ Paul O’Connor __________________________ Jock Lauterer BLURRED LINES 1 ABSTRACT South Africa’s developing democracy, along with globalization and advances in technology, have created a confusing and chaotic environment for the country’s journalists. This research paper provides an overview of the history of the South African press, particularly the “alternative” press, since the early 1900s until 1994, when democracy came to South Africa. Through an in-depth analysis of the African National Congress’s relationship with the press, the commercialization of the press and new developments in technology and news accessibility over the past two decades, the paper goes on to argue that while journalists have been distracted by heated debates within the media and the government about press freedom, and while South African media companies have aggressively cut costs and focused on urban areas, the South African press has lost touch with ordinary South Africans — especially historically disadvantaged South Africans, who are still struggling and who most need representation in news coverage. BLURRED LINES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction A. Background and Purpose B. Research Questions and Methodology C. Definitions Chapter II: Review of Literature A. History of the Alternative Press in South Africa B. Censorship of the Alternative Press under Apartheid Chapter III: Media-State Relations Post-1994 Chapter IV: Profits, the Press, and the Public Chapter V: Discussion and Conclusion BLURRED LINES 3 CHAPTER I: Introduction A. -

An Ageing Anachronism: D.F. Malan As Prime Minister, 1948–1954

An Ageing Anachronism: D.F. Malan as Prime Minister, 1948–1954 LINDIE KOORTS Department of Historical Studies, University of Johannesburg This article tells the behind-the-scenes tale of the first apartheid Cabinet under Dr D.F. Malan. Based on the utilisation of prominent Nationalists’ private documents, it traces an ageing Malan’s response to a changing international context, the chal- lenge to his leadership by a younger generation of Afrikaner nationalists and the early, haphazard implementation of the apartheid policy. In order to safeguard South Africa against sanctions by an increasingly hostile United Nations, Malan sought America’s friendship by participating in the Korean War and British protection in the Security Council by maintaining South Africa’s Commonwealth membership. In the face of decolonisation, Malan sought to uphold the Commonwealth as the preserve of white-ruled states. This not only caused an outcry in Britain, but it also brought about a backlash within his own party. The National Party’s republican wing, led by J.G. Strijdom, was adamant that South Africa should be a republic outside the Commonwealth. This led to numerous clashes in the Cabinet and parliamentary caucus. Malan and his Cabinet’s energies were consumed by these internecine battles. The systematisation of the apartheid policy and the coordination of its implementation received little attention. Malan’s disengaged leadership style implies that he knew little of the inner workings of the various government departments for which he, as Prime Minister, was ultimately responsible. The Cabinet’s internal disputes about South Africa’s constitutional status and the removal of the Coloured franchise ultimately served as lightning conductors for a larger issue: the battle for the party’s leadership, which came to a head in 1954. -

RATE CARD 2018 Contents

RATE CARD 2018 Contents 1. Digital Rates 2. Newspaper Rates 3. Local Titles Insert Rates 4. Magazine Rates 5. Material & Insert Deadlines 6. Column Sizes ϳ͘ dĞƌŵƐĂŶĚŽŶĚŝƟŽŶƐ 8. Contact Details ůůƌĂƚĞƐĂƌĞEĞƩĂŶĚĞdžĐůƵĚĞsd ZĂƚĞƐĞīĞĐƟǀĞƉƌŝůϮϬϭϴʹDĂƌĐŚϮϬϭϵ ĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶĨĞĞǁŝůůďĞĐŚĂƌŐĞĚĨŽƌůĂƚĞĐĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶƐ 1 1. Rates Digital ZĂƚĞƐĂŶĚWƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶ/ŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶMonday - Saturday Click on a heading below to navigate to that page Digital Rates Netwerk 24 City Press Son <ŝĐŬKī Ϯ͘ EĞǁƐƉĂƉĞƌ Netnuus Daily Sun Soccer Laduma Kuier Rates WƌŝŶƚZĂƚĞƐ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ^ĂƚƵƌĚĂLJ Sunday Titles Daily Sun Beeld City Press Son Die Burger Rapport Volksblad Son op Sonday Volksblad 3. Tiltes Local DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJtĞĚŶĞƐĚĂLJ /ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ The Witness & Weekend Witness Sunday Sun Soccer Laduma >ŽĐĂůdŝƚůĞƐ/ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ ĂƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ tĞƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞ͗WĞŶŝŶƐƵůĂdŝƚůĞƐ Maritzburg Echo Isolomzi Express City Vision Lagunya ^ŽƵƚŚŽĂƐƚ&ĞǀĞƌ Kouga Express City Vision Khayelitsha Mid-Karoo Express >ŝŵƉŽƉŽdŝƚůĞƐ ŝƚLJsŝƐŝŽŶ>ǁĂŶĚůĞͬEŽŵnjĂŵŽ 4. Magazine Mthatha Express Rise ‘n Shine People’s Post Athlone Rates PE Express DƉƵŵĂůĂŶŐĂdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚƚůĂŶƟĐ^ĞĂͲŽĂƌĚͬ Queenstown Express ŝƚLJĚŝƟŽŶ UD Express Cosmos News WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚůĂƌĞŵŽŶƚͬ Rondebosch &ƌĞĞ^ƚĂƚĞdŝƚůĞƐ EŽƌƚŚtĞƐƚdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚŽŶƐƚĂŶƟĂͬtLJŶďĞƌŐ Bloemnuus ĂƌůĞƚŽŶǀŝůůĞ,ĞƌĂůĚ WĞŽƉůĞΖƐWŽƐƚ&ĂůƐĞĂLJ Midweek Potchefstroom Herald /ŶƐĞƌƚĞĂĚůŝŶĞƐ Express ϱ͘ DĂƚĞƌŝĂůΘ People's Post Grassy Park Kroonnuus Potchefstroom Herald People's Post Landsdowne Vista Leseding News Bojanala People’s Post Michell’s Plain Vrystaat Nuus EŽƌƚŚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ People’s Post -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS 2 No

Vol. 651 Pretoria 20 September 2019 , September No. 42714 ( PART1 OF 2 ) LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS 2 No. 42714 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 20 SEPTEMBER 2019 STAATSKOERANT, 20 SEPTEMBER 2019 No. 42714 3 Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Eastern Cape / Oos-Kaap ................................................................................................................. 14 Free State / Vrystaat ........................................................................................................................ 15 Limpopo ....................................................................................................................................... 15 North West / Noordwes ..................................................................................................................... 15 Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 15 COMPANY NOTICES • MAATSKAPPYKENNISGEWINGS Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 16 LIQUIDATOR’S AND OTHER APPOINTEES’ NOTICES LIKWIDATEURS EN ANDER AANGESTELDES SE KENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ...................................................................................................................................... -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

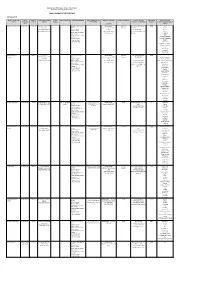

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Annual Report 2010 N T Ann Rrepo P

AnnualAnn RReReportpop rtt 2010 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting 2 Financial highlights 22 Review of operations 42 Governance 74 Consolidated 198 Notice of AGM 4 Group at a glance 24 Internet 51 Sustainability and company 205 Proxy form 6 Global footprInt 30 Pay television 66 Directorate annual financial 8 Chairman’s and 36 Print media 71 Administration and statements managing corporate information director’s report 72 Analysis of 16 Financial review shareholders and shareholders’ diary Entertainment at your fingertips Vision for subscribers To – wherever I am – have access to entertainment, trade opportunities, information and to my friends Naspers Annual Report 2010 1 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting Mission To develop in the leading group media and e-commerce platforms in emerging markets www.naspers.com 2 Naspers Annual Report 2010 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting kgFINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Revenue (R’bn) Ebitda (R’m) Ebitda margin (%) 28,0 6 496 23,2 26,7 6 026 22,6 09 10 09 10 09 10 Headline earnings Core HEPS Dividend per per share (rand) (rand) share (proposed) (rand) 8,84 14,26 2,35 8,27 11,79 2,07 09 10 09 10 09 10 2010 2009 R’m R’m Income statement and cash flow Revenue 27 998 26 690 Operational profit 5 447 4 940 Operating profit 4 041 3 783 Net profit attributable