Deriving Transition Probabilities and Evolutionary Distances from Substitution Rate Matrix by Probability Reasoning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Analysis of the Transition from Wild to Domesticated Cotton (G

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/616763; this version posted April 23, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic analysis of the transition from wild to domesticated cotton (G. hirsutum) Corrinne E. Grover1, Mi-Jeong Yoo1,a, Michael A. Gore2, David B. Harker3,b, Robert L. Byers3, Alexander E. Lipka4, Guanjing Hu1, Daojun Yuan1, Justin L. Conover1, Joshua A. Udall3,c, Andrew H. Paterson5, and Jonathan F. Wendel1 1Department of Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011 2Plant Breeding and Genetics Section, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 3Plant and Wildlife Science Department, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 4Department of Crop Sciences, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801 5Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 acurrent address: Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611 bcurrent address: Department of Dermatology, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390 ccurrent address: Southern Plains Agricultural Research Center, USDA-ARS, College Station, TX, 77845- 4988 Corresponding Author: Jonathan F. Wendel ([email protected]) Data Availability: All data are available via figshare (https://figshare.com/projects/Genetic_analysis_of_the_transition_from_wild_to_domesticated_cotton_G _hirsutum_QTL/62693) and GitHub (https://github.com/Wendellab/QTL_TxMx). Keywords: QTL, domestication, Gossypium hirsutum, cotton Summary: An F2 population between truly wild and domesticated cotton was used to identify QTL associated with selection under domestication. -

Genetic Testing: Background and Policy Issues

Genetic Testing: Background and Policy Issues Amanda K. Sarata Specialist in Health Policy March 2, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33832 Genetic Testing: Background and Policy Issues Summary Congress has considered, at various points in time, numerous pieces of legislation that relate to genetic and genomic technology and testing. These include bills addressing genetic discrimination in health insurance and employment; precision medicine; the patenting of genetic material; and the oversight of clinical laboratory tests (in vitro diagnostics), including genetic tests. The focus on these issues signals the growing importance of public policy issues surrounding the clinical and public health implications of new genetic technology. As genetic technologies proliferate and are increasingly used to guide clinical treatment, these public policy issues are likely to continue to garner attention. Understanding the basic scientific concepts underlying genetics and genetic testing may help facilitate the development of more effective public policy in this area. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes in the nucleus of most cells in their bodies. Chromosomes are composed of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and protein. DNA is composed of complex chemical substances called bases. Proteins are fundamental components of all living cells, and include enzymes, structural elements, and hormones. A gene is the section of DNA that contains the sequence which corresponds to a specific protein. Though most of the genome is similar between individuals, there can be significant variation in physical appearance or function between individuals due to variations in DNA sequence that may manifest as changes in the protein, which affect the protein’s function. -

Characterization of Point Mutations in the Same Arginine Codon in Three Unrelated Patients with Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency

Characterization of point mutations in the same arginine codon in three unrelated patients with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. A Maddalena, … , W E O'Brien, R L Nussbaum J Clin Invest. 1988;82(4):1353-1358. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI113738. Research Article Point mutations in the X-linked ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) gene have been detected at the same Taq I restriction site in 3 of 24 unrelated probands with OTC deficiency. A de novo mutation could be traced in all three families to an individual in a prior generation, confirming independent recurrence. The DNA sequence in the region of the altered Taq I site was determined in the three probands. In two unrelated male probands with neonatal onset of severe OTC deficiency, a guanine (G) to adenine (A) mutation on the sense strand (antisense cytosine [C] to thymine [T]) was found, resulting in glutamine for arginine at amino acid 109 of the mature polypeptide. In the third case, where the proband was a symptomatic female, C to T (sense strand) transition converted residue 109 to a premature stop. These results support the observation that Taq I restriction sites, which contain an internal CG, are particularly susceptible to C to T transition mutation due to deamination of a methylated C in either the sense or antisense strand. The OTC gene seems especially sensitive to C to T transition mutation at arginine codon 109 because either a nonsense mutation or an extremely deleterious missense mutation will result. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/113738/pdf Characterization of Point Mutations in the Same Arginine Codon in Three Unrelated Patients with Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency Anne Maddalena,*" J. -

Indel Information Eliminates Trivial Sequence Alignment in Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Analysis

Cladistics Cladistics 28 (2012) 514–528 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00402.x Indel information eliminates trivial sequence alignment in maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis John S.S. Dentona,b,* and Ward C. Wheelerb,c aDivision of Vertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA; bRichard Gilder Graduate School, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA; cDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA Accepted 12 March 2012 Abstract Although there has been a recent proliferation in maximum-likelihood (ML)-based tree estimation methods based on a fixed sequence alignment (MSA), little research has been done on incorporating indel information in this traditional framework. We show, using a simple model on a single character example, that a trivial alignment of a different form than that previously identified for parsimony is optimal in ML under standard assumptions treating indels as ‘‘missing’’ data, but that it is not optimal when indels are incorporated into the character alphabet. We show that the optimality of the trivial alignment is not an artefact of simplified theory assumptions by demonstrating that trivial alignment likelihoods of five different multiple sequence alignment datasets exhibit this phenomenon. These results demonstrate the need for use of indel information in likelihood analysis on fixed MSAs, and suggest that caution must be exercised when drawing conclusions from software implementations claiming improvements in likelihood scores under an indels-as-missing assumption. Ó The Willi Hennig Society 2012. Maximum likelihood (ML) has become a popular the increasing sophistication of search heuristics in ML optimality criterion for inferring evolutionary trees software (e.g. -

Systematic (Genomic Based)

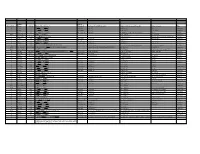

Trivial Codon Exon/Intron Name Codon Nucleotide Change* Changed Systematic(cDNA based) Systematic (genomic based) Other names Type 2 M-1T -1 CCATGGC>CCACGGC Met>Thr c.2T>C g.4895T>C M1T transition 2 R3Op 3 CACCGAT>CACTGAT Arg>Opal c.10C>T g.4903C>T R3X, R3ter transition 2 ∆A20 20 CCC[A]GAG>CCCGAG Gln>Arg (fs) c.62delA g.4955delA (first base of deletion) ∆A20 deletion IVS2 IVS2-1G>A atagGTA>ataaGTA g.5814G>A c.113-1G>A transition 3 IVS2-1∆4 37-38 ata[gGTA]CCA>ataCCA g.5813delGGTA G12/∆3;IVS2-delGGTA;∆4IVS2-E3 deletion 3 R59op 59 TTCCGAG>TTCTGAG Arg>Opal c.178C>T g.5880C>T R59X;R59ter transition 3 I73T 73 GCATCGG>GCACCGG Ile>Thr c.221T>C g.5923T>C transition 3 L83∆C 83 CCT[C]TAC>CCTTAC Leu>Leu(fs) c.252delC g.5954delC c.250 delC deletion 3 1123ins12 104 GGT[]GGG>GGT[GGGGATCGTGGT]GGG c.314^315ins12 g.6016^6017insGGGGATCGTGGT —12E3;V104+GIVV insertion IVS3 K107K∆12 104-107del GTG[GTGGGAATCAAG]gtt>GTGgtgggaatcaaagtt c.324G>A;delGTGGGAATCAAG(312-324) g.6026G>A g.1133G>A transition IVS3 IVS3-1G>A acagTTA>acaaTTA g.7257G>A c.325-1G>C, g.8180G>C,IVS3sas transversion 4 ∆28E4 114-151 TCC[TCTTGCAGGAACAAACAAAGAAACCACC]ATT>TCCATT Pro>Pro(fs) c.345-372del28 g.7277^7305del c.345_72del28 deletion 4 Q110Oc 110 GACCAAG>GACTAAG Gln>Ochre c.331C>T g.7264C>T transition 4 ∆4E4 118-120 GAAC[AAAC]AAAG>GAACAAAG c.357delAAAC g.7289delAAAC ∆4, MD∆4 deletion 4-5 ∆E4-E5 ccc[tgt…TCC]AGC>cccAGC g.6594^8239del F13/∆4,5 deletion 5 C134R 134 CGCTGTG>CGCCGTG Cys>Arg c.403T>C g.8162T>C C135R transition 5 W147R 147 AAGTGGC>AAGCGGC Trp>Arg c.442T>C g.8201T>C W148R transition -

G14TBS Part II: Population Genetics

G14TBS Part II: Population Genetics Dr Richard Wilkinson Room C26, Mathematical Sciences Building Please email corrections and suggestions to [email protected] Spring 2015 2 Preliminaries These notes form part of the lecture notes for the mod- ule G14TBS. This section is on Population Genetics, and contains 14 lectures worth of material. During this section will be doing some problem-based learning, where the em- phasis is on you to work with your classmates to generate your own notes. I will be on hand at all times to answer questions and guide the discussions. Reading List: There are several good introductory books on population genetics, although I found their level of math- ematical sophistication either too low or too high for the purposes of this module. The following are the sources I used to put together these lecture notes: • Gillespie, J. H., Population genetics: a concise guide. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and Lon- don, 2004. • Hartl, D. L., A primer of population genetics, 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Publishers, 1988. • Ewens, W. J., Mathematical population genetics: (I) Theoretical Introduction. Springer, 2000. • Holsinger, K. E., Lecture notes in population genet- ics. University of Connecticut, 2001-2010. Available online at http://darwin.eeb.uconn.edu/eeb348/lecturenotes/notes.html. • Tavar´eS., Ancestral inference in population genetics. In: Lectures on Probability Theory and Statistics. Ecole d'Et´esde Probabilit´ede Saint-Flour XXXI { 2001. (Ed. Picard J.) Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer Verlag, 1837, 1-188, 2004. Available online at http://www.cmb.usc.edu/people/stavare/STpapers-pdf/T04.pdf Gillespie, Hartl and Holsinger are written for non-mathematicians and are easiest to follow. -

CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Base-Editing and Prime-Editing

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Base-Editing and Prime-Editing Ariel Kantor 1,2,*, Michelle E. McClements 1,2 and Robert E. MacLaren 1,2 1 Nuffield Laboratory of Ophthalmology, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences & NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK 2 Oxford Eye Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 25 August 2020; Published: 28 August 2020 Abstract: Many genetic diseases and undesirable traits are due to base-pair alterations in genomic DNA. Base-editing, the newest evolution of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas-based technologies, can directly install point-mutations in cellular DNA without inducing a double-strand DNA break (DSB). Two classes of DNA base-editors have been described thus far, cytosine base-editors (CBEs) and adenine base-editors (ABEs). Recently, prime-editing (PE) has further expanded the CRISPR-base-edit toolkit to all twelve possible transition and transversion mutations, as well as small insertion or deletion mutations. Safe and efficient delivery of editing systems to target cells is one of the most paramount and challenging components for the therapeutic success of BEs. Due to its broad tropism, well-studied serotypes, and reduced immunogenicity, adeno-associated vector (AAV) has emerged as the leading platform for viral delivery of genome editing agents, including DNA-base-editors. In this review, we describe the development of various base-editors, assess their technical advantages and limitations, and discuss their therapeutic potential to treat debilitating human diseases. -

Transition Bias Influences the Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/421651; this version posted September 20, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Transition bias influences the evolution of antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium 2 tuberculosis 3 Joshua L. Payne1,2π*, Fabrizio Menardo3,4 π, Andrej Trauner3,4, Sonia Borrell3,4, Sebastian M. 4 Gygli3,4, Chloe Loiseau3,4, Sebastien Gagneux3,4†, Alex R. Hall1† 5 1. Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zurich, Switzerland 6 2. Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Lausanne, Switzerland 7 3. Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland 8 4. University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland 9 *Correspondence: [email protected] 10 π, These authors contributed equally. 11 †These authors also contributed equally. 12 13 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/421651; this version posted September 20, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 14 Abstract 15 Transition bias, an overabundance of transitions relative to transversions, has been widely 16 reported among studies of mutations spreading under relaxed selection. However, demonstrating 17 the role of transition bias in adaptive evolution remains challenging. We addressed this challenge 18 by analyzing adaptive antibiotic-resistance mutations in the major human pathogen 19 Mycobacterium tuberculosis. -

Personalized Genetic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns

Journal of Personalized Medicine Review Personalized Genetic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns Olga María Diz 1,2,† , Rocio Toro 3,† , Sergi Cesar 4, Olga Gomez 5,6, Georgia Sarquella-Brugada 4,7,*,‡ and Oscar Campuzano 2,7,8,*,‡ 1 UGC Laboratorios, Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, 11009 Cadiz, Spain; [email protected] 2 Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics Department, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, 08950 Barcelona, Spain 3 Medicine Department, School of Medicine, Cádiz University, 11519 Cadiz, Spain; [email protected] 4 Arrhythmia, Inherited Cardiac Diseases and Sudden Death Unit, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, 08007 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Fetal Medicine Research Center, BCNatal-Barcelona Center for Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine (Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Deu), Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, 08950 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 6 Centre for Biomedical Research on Rare Diseases (CIBER-ER), 28029 Madrid, Spain 7 Medical Science Department, School of Medicine, University of Girona, 17003 Girona, Spain 8 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red, Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBER-CV), 28029 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.S.-B.); [email protected] (O.C.) † Equally as co-first authors. ‡ Contributed equally as co-senior authors. Citation: Diz, O.M.; Toro, R.; Cesar, Abstract: Congenital heart disease is a group of pathologies characterized by structural malforma- S.; Gomez, O.; Sarquella-Brugada, G.; tions of the heart or great vessels. -

Botany Honours

BOTANY HONOURS SEMESTER IV CORE COURSE 10 GENETICS (BOT-A-CC-4-10-TH) TOPIC NO 6: MUTATION Dr. Madhuvanti Chatterjee MAULANA AZAD COLLEGE KOLKATA DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY MUTATION The term MUTATION is defined as any sudden heritable change in the genotype of an organism, not explainable by recombination of preexisting genetic variability, and the process by which the change occurs. Topic no- 6.1. Point mutation-Transition, Transversion and Frame shift mutation POINT MUTATION: Mutation which involve the deletion /duplication /substitution of SINGLE BASE – PAIRS are known as point mutation. Transition : Mutations which involve the replacement of a Purine with a purine (A G) OR pyrimidine with another pyrimidine (T C). Transversion : Mutations which involve the replacement of a Purine with a pyrimidine OR Pyrimidine with a purine. T A G Purine Transition Transversion Pyrimidine C Diagrammatic representation of substitutions possible in DNA Frame shift mutation : A mutation which involves the addition or deletion of one or a few base and results in the alteration of the reading frame of the codons in the gene (corresponding amino acids of the polypeptide) distal to the mutation. Diagram showing the change from the third amino acid in the polypeptide as a result of addition of a single base pair (C/G) in the mutant (Right panel) MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF MUTATION I. TAUTOMERISATION :- The rare forms of the bases which are formed due to the change of the position of the hydrogen atoms from one position to another in the purine or pyrimidine Fig 1 Fig 1: Tautomeric shifts- The more stable keto forms of Thymine and Guanine change to the less stable enol forms AND the stable amino forms of Cytosine and Adenine change to less stable imino forms. -

Sequence Analysis of N-Ethyl-N-Nitrosourea-Inducedvermilion Mutations in Drosophila Melanogaster

Copyright 0 1989 by the Genetics Society of America Sequence Analysis of N-Ethyl-N-Nitrosourea-Inducedvermilion Mutations in Drosophila melanogaster Albert Pastink,*.+ Cees Vreeken,*’+ MadeleineJ. M. Nivard,* Lillie L. Searles* and Ekkehart W. Vogel* *Department of Radiation Genetics and Chemical Mutagenesis, State University of Leiden, Sylvius Laboratories, Wassenaarseweg 72, 2333 AL Leiden, The Netherlands, 7.A. Cohen Institute, Interuniversity Research Institute for Radiopathology and Radiation Protection, The Netherlands, and $Department of Biology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514 Manuscript received February 2 1, 1989 Accepted for publicationMay 8, 1989 ABSTRACT The mutational specificity of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) was determined in Drosophila melano- gaster using the vermilion locus as a target gene. 25 mutants (16F1 and 9 F2 mutants) were cloned and sequenced. Only base-pair changes were observed; three of the mutants represented double base substitutions. Transition mutations were the most prominent sequence change:61% were GC+AT and 18%AT4C substitutions. Both sequence changes can be explainedby the miscoding properties of the modified guanine and thymine bases.A strong bias of neighboring bases on the occurrence of the GC+AT transitions or a strand preferenceof both types of transition mutationswas not observed. The spectrum of ENU mutations in D. melanogaster includes a significant fraction(2 1 %) of transversion mutations. Our dataindicate that like in other prokaryoticand eukaryotic systems also in I). melanogaster the0‘“ethylguanine adduct is the most prominent premutational lesion after ENU treatment. The strong contribution of the 06-ethylguanine adduct to the mutagenicity of ENU possibly explains the absenceof distinct differences between the typeof mutations observedin the F1 and F:! mutants. -

The Rate and Molecular Spectrum of Spontaneous Mutations in the GC-Rich Multichromosome Genome of Burkholderia Cenocepacia

GENETICS | INVESTIGATION The Rate and Molecular Spectrum of Spontaneous Mutations in the GC-Rich Multichromosome Genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia Marcus M. Dillon,* Way Sung,† Michael Lynch,† and Vaughn S. Cooper*,1 *Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Biomedical Sciences, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, and †Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405 ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7726-0765 (V.S.C.) ABSTRACT Spontaneous mutations are ultimately essential for evolutionary change and are also the root cause of many diseases. However, until recently, both biological and technical barriers have prevented detailed analyses of mutation profiles, constraining our understanding of the mutation process to a few model organisms and leaving major gaps in our understanding of the role of genome content and structure on mutation. Here, we present a genome-wide view of the molecular mutation spectrum in Burkholderia cenocepacia, a clinically relevant pathogen with high %GC content and multiple chromosomes. We find that B. cenocepacia has low genome-wide mutation rates with insertion–deletion mutations biased toward deletions, consistent with the idea that deletion pressure reduces prokaryotic genome sizes. Unlike prior studies of other organisms, mutations in B. cenocepacia are not AT biased, which suggests that at least some genomes with high %GC content experience unusual base-substitution mutation pressure. Impor- tantly, we also observe variation in both the rates and spectra of mutations among chromosomes and elevated G:C . T:A transversions in late-replicating regions. Thus, although some patterns of mutation appear to be highly conserved across cellular life, others vary between species and even between chromosomes of the same species, potentially influencing the evolution of nucleotide composition and genome architecture.