1106555 [2011] RRTA 1039 (12 December 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgroun Dj (IN BLOCK LETTERS) 2

ps 2020 FUNCfIONARY / PROTOCOL GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN Space for CABINET SECRETARIAT (AVIATION DIVISION) Photograph AIRPORTS SECURITY FORCE (Only White APPLICATION FOR AIRPORT ENTRY PASS-2020 I. Name of Applicant._---.,..--,..--:-=:-:-::==-=::-- _ Backgroun dJ (IN BLOCK LETTERS) 2. Designation I Branch Pay Scale IGroup _ (Passport Size) 3. Department Service No. _ 2" x 1 ~" 4. Nationality Date & Place of Birth _ 5. CNIC No. Passport/Diplomatic Identity Card No. _:__-----:--,------ (For Pakistani National) "" _ (For Foreigners/Diploma 6. Father's/Husband Name of the Applicant, _ 7. Present Address _ 8, Permanent Residential Address: --, _ 9. Telephone No. Office Res. Fax Mob No. _ E-mail _ 10. SECURITY CLEARANCE a) By Int. Bureau vide letter No. Dated _ b) By Spl. Branch vide letter No. Dated _ c) Departmental Head Clearance _ I I. Area/Airport Required a) Area _ b) Ai~ort _ 12. Justification for which purpose pass is required. 13. Previous Year's Airport Entry Pass No. (if issued). Reg. No. _ CERTIFICATE / UNDERTAKING • The information given above is correct in all respect. • I will comply with all Security Rules and aware that any violation may result in cancellation of the Airport Entry Pass besides legal action. • I will return the Airport Entry Pass on its expiry or on relinquishing of charge when no longer required. • I have read and understood the instructions overleaf fully. I shall abide by the same. Note The Pass will be displayed on the chest while entering airport premises otherwise entry will be denied. The Pass will be displayed at all times while in restricted area of the airport. -

Police Organisations in Pakistan

HRCP/CHRI 2010 POLICE ORGANISATIONS IN PAKISTAN Human Rights Commission CHRI of Pakistan Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative working for the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth Human Rights Commission of Pakistan The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) is an independent, non-governmental organisation registered under the law. It is non-political and non-profit-making. Its main office is in Lahore. It started functioning in 1987. The highest organ of HRCP is the general body comprising all members. The general body meets at least once every year. Executive authority of this organisation vests in the Council elected every three years. The Council elects the organisation's office-bearers - Chairperson, a Co-Chairperson, not more than five Vice-Chairpersons, and a Treasurer. No office holder in government or a political party (at national or provincial level) can be an office bearer of HRCP. The Council meets at least twice every year. Besides monitoring human rights violations and seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying and intervention in courts, HRCP organises seminars, workshops and fact-finding missions. It also issues monthly Jehd-i-Haq in Urdu and an annual report on the state of human rights in the country, both in English and Urdu. The HRCP Secretariat is headed by its Secretary General I. A. Rehman. The main office of the Secretariat is in Lahore and branch offices are in Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta. A Special Task Force is located in Hyderabad (Sindh) and another in Multan (Punjab), HRCP also runs a Centre for Democratic Development in Islamabad and is supported by correspondents and activists across the country. -

In This Act, Unless There Is Anything Repugnant in Lhe Subject Or Context

@s INTRODUCIID IN'IHE NA-tlOrr-AI- ASSIIMBLYI A BILL to provide for a system of administration of justice, maintenance of peace ,)nd good governance in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Protected or Administered Areas WHEREAS it is expedient to provide for a system of administration ot lustice, maintenance of peace and good governance in the Federally Admrnistered Tribal Areas and Protected or Admrnrstered Areas for matters connected therewith and ancillary thereto; It rs hereby enacted as Follows:- 1. Short title and commencement.-( 1) fhis Act may be called the Triba Areas Rewal Act,2077. (2) It shali come into force in such Federally Administered Tribal Area or Areas mentioned in the Frrst Schedule as Protected or Adrn nistered Areas or any part thereof as the Federal Government may, by notification in the official Gazefte, determine, 2. Definitions.- In this Act, unless there is anything repugnant in lhe subject or context,-- (a) "Councrl of Elders" means a )irga of four or more respectable elders aDpointed under sections 8 or i0, as the case may be, and presided over by the Judge; (b) "Cou.t means the Court comprising,- (i) the ludqe; and (ii) the Councrl of Elders; (b) "CPC" means the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (Act V of 1908) as applicable in the Province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; (d) "Cr.PC" rneans the Code of Criminal procedure, 1898 (Act V of 1898 ); (e) "FATA" means the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and such other areas as specified in the First Schedule; (f) "Judge' means a judicial officer appornted by the Federal Government to exercise powers under this Act, Cr.PC and cPc; (S) "prescribed" means prescribed by rules made under this Act; (h) "Protected Area or Administered Area" means the Areas specrfi€d in the First Schedule; (i) "Qaumt Jirga" means a lirga consisting of respectablq elders and retresentatives of the tribes; (l) "Rewaj' means customs, traditions and usages of the tribes in vogue i'r FATA; and (k) "Schedule" means a Schedule to this Act 3. -

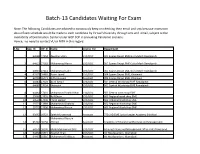

Batch-13 Candidates Waiting for Exam

Batch-13 Candidates Waiting For Exam Note: The following Candidates are advised to consciously keep on checking their email and sms because intimation about Exam schedule would be made to each candidate by Virtual University through sms and email, subject to the availability of Examination Center under GOP SOP in prevailing Pandemic scenario. Hence, no need to contact VU or NITB in this regard. S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For Department 1 64988 17254 Zeeshan Ullah LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 2 64923 17262 Muhammad Harris LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 3 64945 17261 Muhammad Tahir LDC/UDC 301 Spares Depot EME Golra Morh Rawalpindi 4 62575 16485 Aamir Javed LDC/UDC 304 Spares Depot EME, Khanewal 5 63798 16471 Jaffar Hussain Assistant 304 Spares Depot EME, Khanewal 6 64383 17023 Asim Ismail LDC/UDC 501 Central Workshop EME Rawalpindi 7 64685 17024 Shahrukh LDC/UDC 501 Central Workshop EME Rawalpindi 8 64464 17431 Muhammad Shahid Khan LDC/UDC 502 Central work shop EME 9 29560 17891 Asif Ehsan LDC/UDC 602 Regional work shop EME 10 64540 17036 Imran Qamar LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 11 29771 17889 Muhammad Shahroz LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 12 29772 17890 Muhammad Faizan LDC/UDC 602 Regional Workshop EME 13 63662 16523 Saleh Muhammad Assistant 770 LAD EME Junior Leader Academy Shinikiari Muhammad Naeem 14 65792 18156 Ahmed Assistant Academy of Educational Planning and Management 15 64378 18100 Malik Muhammad Bilal LDC/UDC Administrative and Management office GHQ Rawalpind 16 64468 16815 -

Rules of Business 1973

For official use only RULES OF BUSINESS 1973 (As amended up to 27th May, 2021) CABINET SECRETARIAT (Cabinet Division) Islamabad [Ministerial-I Section] T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S PART A.—GENERAL Rule Page 1. Title and commencement…..……………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Definitions…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 -2 3. Allocation of Business………………………………………………………………………………….….3 4. Organization of Divisions……………………………………………………………………………… 3 5. Transaction of Business………………………………………………………………………………. 4-5 6. Individual and collective responsibility…………………………………………………………… 5 7. Orders and instruments, agreements and contracts………………………………………… 5-6 PART B.—CONSULTATION AMONG DIVISIONS 8. Inter-Division procedure………………………………………………………………………………… 6-7 9. Secretaries’ Committee…………………………………………………………………………………….7 10. Consultation with the Cabinet Division …………………………………………………………… 8 11. Consultation with the Establishment Division ………………………………………………… 8 12. Consultation with the Finance Division …………………………………………………………… 9 13. Consultation with Foreign Affairs Division ………………………………………………………. 9 14. Consultation with the Law and Justice Division....................................................................................... 10 14A. Consultation with the Revenue Division …………………………………………………………. 10 PART C.—REFERENCES TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND THE PRESIDENT 15. Reference to the Prime Minister ………………………………………………………………. 11-12 15A. Reference to the President……………………………………………………………………………… 12 PART D.—CABINET PROCEDURE 16. Cases to be brought before Cabinet -

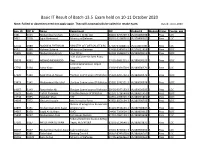

Basic IT Result of Batch-13.5 Exam Held on 10-11 October 2020

Basic IT Result of Batch-13.5 Exam held on 10-11 October 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Dated: 10-11-2020 App_ID Off_Sr Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status Course_app 7441 2515 Muhammad Usman Defence / GHQ/ AST 38201-0703749-3 VU170400498 3 Pass LDC 7437 2518 Sajid Mehmood Ministry of Defence 38201-5218076-5 VU170400501 3 Pass LDC 12741 2989 NOSHABA EHTISHAM MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS 37405-0320841-2 VU170403780 3 Pass LDC 4992 1360 Kishwer Sultana Ministry of Defence 37405-5949699-2 VU170911618 3 Pass UDC 15385 4801 Muhammad Akram Post Office 32403-1626012-5 VU180600112 3 Pass UDC FGEI (C/G) Dte Sir Syed Road, 15078 4952 ARSHAD MEHMOOD Rwp 37401-9681211-1 VU180600225 3 Pass UDC Central Ammunition Depot 17756 5134 Azhar Khan Sargodha 13102-0361678-9 VU180600371 3 Pass LDC 17126 5140 Syed Waji-ul-Hassan Election Commission of Pakistan 35202-2205762-1 VU180600376 3 Pass UDC 13823 5142 Muhammad Khurshid Election Commission Of Pakistan 35202-2741551-3 VU180600378 3 Pass UDC 14057 5149 Rana Arslan Ali Election Commission of Pakistan 38403-9977153-3 VU180600385 3 Pass LDC 22523 6566 Farhat Yasmeen Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 61101-1718744-8 VU180601452 3 Pass UDC 21738 7055 Abdullah Khan PAF 14301-1998716-7 VU180601861 3 Pass UDC 24009 7972 Ghulam Hussain Anti Narcotics Force 45302-8650164-3 VU180700703 3 Pass UDC Bureau of emigration & overseas 24899 8151 Muhammad Azim Awan employment 61101-9516133-1 VU180700847 3 Pass LDC 24067 8178 Saqib Ali Siddiqui GHQ -

For the Meeting of the National Assembly to Be Held on Tuesday, the 30Th June, 2020 at 11.00 A.M

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT ORDERS OF THE DAY for the meeting of the National Assembly to be held on Tuesday, the 30th June, 2020 at 11.00 a.m. SUPPLEMENTARY BUDGET 1. Tilawat, Naat and national anthem. 2. General discussion on Supplementary Demands for Grants and Appropriations for the financial year 2019-2020. 3. DISCUSSION under clause (1) of Article 82 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan on the charged expenditure as shown in the Supplementary Demands for Grants and Appropriations for the financial year 2019-2020. Demand Number/ Amount Service and Purpose Appropriation Rs 79. Other Expenditure of Law and Justice Division 13,000 86. The Senate 1,000 ---- Staff, Household and Allowances of the President 8,000 ---- Supreme Court 3,000 ---- Election 57,000 ---- Wafaqi Mohtasib 72,000 Total: 154,000 4. DISCUSSION and voting on Supplementary demands for Grants in respect of expenditure other than charged upon the Federal consolidated fund for the financial year 2019-2020. 1. Mr. Muhammad Hammad Azhar, Minister for Industries and Production to move: That a Supplementary sum not exceeding of Rs 12,000/- be granted to the Federal Government to meet expenditure during the financial year ending 30th June, 2020 in respect of CABINET DIVISION (Demand No.2). 2 2. Mr. Muhammad Hammad Azhar, Minister for Industries and Production to move: That a Supplementary sum not exceeding of Rs 1,250,004,000/- be granted to the Federal Government to meet expenditure during the financial year ending 30th June, 2020 in respect of OTHER EXPENDITURE OF CABINET DIVISION (Demand No.4). -

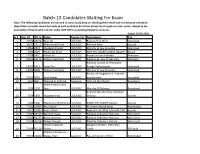

Batch-15 Candidates Waiting for Exam

Batch-15 Candidates Waiting For Exam Note: The following Candidates are advised to consciously keep on checking their email and sms because intimation about Exam schedule would be made to each candidate by Virtual University through sms and email, subject to the availability of Examination Center under GOP SOP in prevailing Pandemic scenario. Dated: 10-03-2021 Sr # App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For Department City 1 75542 23163 Noor Ali LDC/UDC Regional Tax Office Islamabad 2 39077 22111 Muhammad Tariq LDC/UDC Pakistan Navy Karachi 3 12855 2822 Muqbool Ahmed LDC/UDC Ministry of Law & Justice Islamabad 4 4995 1025 MAJID ALI KHAN LDC/UDC AMF PAC BOARD KAMRA (MoDP) Attock 5 19298 5431 Adnan Ali LDC/UDC Postal Services Pakistan Peshawar 6 29039 10173 Muhammad hanif LDC/UDC Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Peshawar Pakistan Council of Renewable 7 18155 5413 Sadar Din LDC/UDC Energy Technologies Islamabad 8 13701 4000 Muhammad Islam LDC/UDC Ministry of Law & Justice, Islamabad Bureau of emigration & overseas 9 25935 8315 Saad Nawaz LDC/UDC employment islamabad 10 4537 992 Muneeb ur Rehman Assistant GHQ, PS Directorate Rawalpindi Muhammad Junaid 11 2296 1174 Ilyas LDC/UDC Ministry Of Defence Rawalpindi Airports Security Force /Aviation 12 5876 1403 Muzaffar Khan LDC/UDC Division Karachi 13 2933 1000 Mahmood UR Rehman LDC/UDC PNMIT DTE KS&EW Karachi Karachi 14 74369 22085 Nasir Bashir LDC/UDC FF Centre Record Wing Abbottabad 15 70352 22086 Yusra Sohail LDC/UDC Regional Tax Office-I,Karachi, FBR Karachi. 16 71005 20526 Zahid Ali Awan Assistant Pakistan Ordnance Factories Wah Cantt 17 71010 20527 Aamir Waheed LDC/UDC Pakistan Ordnance Factories Wah Cantt 18 71014 20528 Nabeel Ahmad LDC/UDC Pakistan Ordnance Factory Wah Cantt Muhammad Zain Weapons Factory, POFs Wah 19 71306 20529 Shahid LDC/UDC Cantt. -

Aviation Division, Year Book for 2015-16

Year Book 2015-2016 GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT AVIATION DIVISION ISLAMABAD Year Book 2015-2016 GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT AVIATION DIVISION ISLAMABAD Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif Prime Minister of Pakistan (Minister In-Charge) Shujaat Azeem Advisor to the Prime Minister on Aviation Sq. Ldr (Retd.) Muhammad Irfan Elahi Federal Secretary Aviation Foreword The Year-Book of the Aviation Division has been prepared in pursuance of Rule 25(2) of the Rules of Business, 1973. This book contains vision and details of functions, organization, activities and achievements of the Aviation Division and its attached departments/organizations for the financial year 2015-16. It contains information which may be of interest for the academia, researchers and relevant stakeholders. The Aviation Division was established in June 2013 as a part of the Cabinet Secretariat. It had earlier been a wing under the Ministry of Defence. In a short span of time, Division has focused on safety, security and quality standards of aviation industry. Beside this, bilateral and multilateral liberalization; lowering taxes; stimulating economy through tourism, trade, etc.; public private partnership and infrastructural development are the areas under focus. I hope that this book will prove useful for all interested. Muhammad Irfan Elahi Secretary Aviation Division Cabinet Secretariat Islamabad Table of Contents AVIATION DIVISION .................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... -

Moderator and Speaker Profiles Mr

Moderator and Speaker Profiles Mr. Komlan Adonko, Director, AVSEC, National Agency of Civil Aviation of Togo, Togo Mr. Adonko started working for the Civil Aviation Administration of Togo in 1994 as an Economist Manager before being assigned in 1999 in the division in charge of Civil Aviation Security (AVSEC). After his AVSEC training, including AVSEC PMC, he was appointed in 2010 as Director AVSEC/FAL, a post held until today at the National Civil Aviation Administration of Togo. At the international level, he is an ICAO certified instructor and auditor for AVSEC since 2005 and 2014 respectively, as well as a West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) certified auditor for AVSEC. Mr. David Aguilar, Principal, Global Security and Innovative Strategies (GSIS) David Aguilar is a Principal at GSIS. At GSIS, Mr. Aguilar advises clients on a broad range of national homeland and international security matters including border security and logistics, global trade and commerce, supply chain management and security, risk management, viability assessments, and strategic planning and implementation. Mr. Aguilar focuses on tailoring global risk management solutions related to supply chain security, customs compliance, and all issues related to border protection at and between international ports of entry. Mr. Aguilar had a distinguished 35 year career in federal law enforcement, having previously led the United States’ largest law enforcement organization, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Prior to leading CBP, he was appointed by President George W. Bush as the National Chief of the United States Border Patrol. He previously served as Chief of the Tucson Sector and in various leadership positions within the U.S. -

Rules of Business 1973

For official use only RULES OF BUSINESS 1973 (As amended up to 27th May, 2021) CABINET SECRETARIAT (Cabinet Division) Islamabad [Ministerial-I Section] T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S PART A.—GENERAL Rule Page 1. Title and commencement…..……………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Definitions…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 -2 3. Allocation of Business………………………………………………………………………………….….3 4. Organization of Divisions……………………………………………………………………………… 3 5. Transaction of Business………………………………………………………………………………. 4-5 6. Individual and collective responsibility…………………………………………………………… 5 7. Orders and instruments, agreements and contracts………………………………………… 5-6 PART B.—CONSULTATION AMONG DIVISIONS 8. Inter-Division procedure………………………………………………………………………………… 6-7 9. Secretaries’ Committee…………………………………………………………………………………….7 10. Consultation with the Cabinet Division …………………………………………………………… 8 11. Consultation with the Establishment Division ………………………………………………… 8 12. Consultation with the Finance Division …………………………………………………………… 9 13. Consultation with Foreign Affairs Division ………………………………………………………. 9 14. Consultation with the Law and Justice Division....................................................................................... 10 14A. Consultation with the Revenue Division …………………………………………………………. 10 PART C.—REFERENCES TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND THE PRESIDENT 15. Reference to the Prime Minister ………………………………………………………………. 11-12 15A. Reference to the President……………………………………………………………………………… 12 PART D.—CABINET PROCEDURE 16. Cases to be brought before Cabinet -

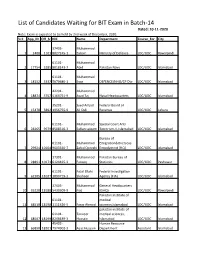

List of Candidates Waiting for BIT Exam in Batch-14 Dated: 10-11-2020 Note: Exam Is Expected to Be Held by 2Nd Week of December, 2020

List of Candidates Waiting for BIT Exam in Batch-14 Dated: 10-11-2020 Note: Exam is expected to be held by 2nd week of December, 2020. Slr# App_ID Off_Sr NIC Name Department Course_For City 37405- Muhammad 1 2400 1101 8027245-1 Zubair Ministry of Defence LDC/UDC Rawalpindi 61101- Muhammad 2 17754 5285 8018143-7 Abid Pakistan Navy LDC/UDC Islamabad 61101- Muhammad 3 18152 5337 5079680-1 Ilyas DEFENCE/NHQ/CP Dte LDC/UDC Islamabad 42201- Muhammad 4 18874 5757 5164751-9 Asad Taj Naval Headquarters LDC/UDC Islamabad 35201- Syed Amjad Federal Board of 5 15478 5892 1956755-9 Ali Quli Revenue LDC/UDC Lahore 61101- Muhammad Special Court Anti 6 28265 9979 8508310-3 Sufian saleem Terrorism-II, Islamabad LDC/UDC Islamabad Bureau of 61101- Muhammad Emigration&Overseas 7 29924 10104 9603340-7 Zahid Qureshi Empolyment [HQ] LDC/UDC islamabad 17301- Muhammad Pakistan Bureau of 8 28891 10171 6124425-3 Farooq Statistics LDC/UDC Peshawar 61101- Fazal Ellahi Federal Investigation 9 62305 18187 1890719-3 Shaheen Agency (FIA) LDC/UDC Islamabad 37405- Muhammad General Headquarters 10 35228 18188 5430309-9 Fiaz (GHQ) LDC/UDC Rawalpindi Pakistan institute of 61101- medical 11 68510 18198 1111326-5 Faraz Ahmed sciences,Islamabad LDC/UDC Islamabad pakistan institute of 61101- Tanveer medical sciences, 12 68507 18199 8248189-3 Hussain Islamabad LDC/UDC Islamabad 45402- Human Resource 13 66890 18201 7974902-3 Aijaz Hussain Department Assistant Islamabad List of Candidates Waiting for BIT Exam in Batch-14 Dated: 10-11-2020 Note: Exam is expected to be held by 2nd week of December, 2020.