La Bella Principessa and the Warsaw Sforziad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bird in the Hand Is Worth Two in the Bush

S T Y L E 生活時尚 15 TAIPEI TIMES • WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 4, 2010 EXHIBITIONS Jawshing Arthur Liou, The Insatiable (2010). PHOTO COURTESY OF TAIPEI ARTIST VILLAGE Taipei Artist Village is holding exhibitions by artists who have spent the past few months in their residency program. First up, Taiwan-born, US-based artist Jawshing Arthur Liou (劉肇興) employs video and animation installation to delve into the culinary practices of different cultures in Things That Are Edible (食事). With titles such as Round (圓) and The Insatiable (未央), Liou’s videos are also an ironic look at our gluttonous times. ■ Barry Room, Taipei Artist Village (台北國際 藝術村百里廳), 7 Beiping E Rd, Taipei City (台北市北平東路7號). Open daily from 10am to 7:30pm. Tel: (02) 3393-7377 ■ Opening reception on Saturday at 7pm. Until Aug. 29 Meanwhile, out at Grass Mountain Village, a collective of young photographers called Invalidation Brothers (無效兄弟) — Chiu Chih- A bird in the hand is worth hua (丘智華), Tien Chi-chuan (田季全), Lee Ming-yu (李明瑜) and Lin Cheng-wei (林正偉) — have snapped images of religious rituals with mountain scenes as a backdrop. Entitled Penglai Grass Mountain (蓬萊仙山), these two in the bush black-and-white photos point at the ubiquity of the sacred in our mundane lives. ■ Grass Mountain Artist Village (草山國際藝術 Researchers unveil the ‘holy grail’ of Audubon illustration 村), 92 Hudi Rd, Taipei City (台北市湖底路92號). Open Wednesdays to Sundays from 10am to BY JON HURDLE 4pm. Tel: (02) 2862-2404 REUTERS, PHILADELPHIA ■ Opening reception on Saturday at 11am. Until Sept. 5 esearchers have found the first because it was at a significant turning in the Journal of the Early Republic, in 1825 and its only other branch, in published illustration by John point in his life.” an historical periodical, this fall. -

Or Leonardo Da

GVIR_A_522394.fm Page 382 Saturday, September 18, 2010 1:48 AM 382 Reviews La Bella Principessa: The Story of a New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci (or Leonardo da Vinci “La Bella Principessa”: The Profile Portrait of a Milanese Woman) by Martin Kemp and Pascal Cotte, with contributions by Peter Paul Biro, Eva Schwan, 5 Claudio Strinati, and Nicholas Turner London, Hodder & Stoughton, 2010 208 pp., illustrated, some color, £18.99 (cloth). ISBN: 978-1-444-70626-0 Reviewed by David G. Stork 10 On 30 January 1998, an exceptionally elegant profile portrait of a young woman, executed on vellum in black, red, and white chalk (trois crayon) and highlighted with pen and ink, was purchased at Christie’s auction house for US$21,850. 15 Although it was cataloged “German School, Early 19th Century,” as images of the drawing passed among experts, a few scholars tentatively dared to utter the “L word” and suggest that the portrait was a major discovery: a new work by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). 20 This book, by Martin Kemp, an expert on Leonardo and professor of the history of art at Oxford University (recently emeritus), and Pascal Cotte, a founder and director of research at Paris-based Lumière Technology, a firm pioneering the application of high-resolution multispectral imag- ing of art, presents evidence and arguments that the portrait is indeed by Leonardo, 25 and proposes both a date of execution (mid-1490s) as well as the identity of its subject, Bianca Sforza (1482–1496), Duke Ludovico Sforza’s illegitimate daughter. The authors are unequivocal in their conclusion: “With respect to the accumulation of interlocking reasons, we have gathered enough evidence here to confirm that ‘La Bella Principessa’ is indeed by Leonardo” (p. -

La Herencia Recibida 2 Sumario Jueves, 8 De Diciembre De 2011

Nº 763- 8 de diciembre de 2011 - Edición Nacional SEMANARIO CATÓLICO DE INFORMACIÓN Hispanoamérica: 200 años de independencia La herencia recibida 2 Sumario jueves, 8 de diciembre de 2011 LA FOTO 6 3-5 CRITERIOS 7 Etapa II - Número 763 CARTAS 8 Edición Nacional Bicentenario VER, OÍR Y CONTARLO 9 de las Repúblicas AQUÍ Y AHORA iberoamericanas: EDITA: Palacio episcopal de Astorga: Fundación San Agustín. Es hora de hacer Arzobispado de Madrid una lectura justa Arte por dentro y por fuera. 12 de la Historia Cardenal Rouco: DELEGADO EPISCOPAL: Alfonso Simón Muñoz El futuro nos preocupa 13 TESTIMONIO 14 REDACCIÓN: EL DÍA DEL SEÑOR 15 Calle de la Pasa, 3-28005 Madrid. RAÍCES 16-17 Téls: 913651813/913667864 10-11 Fax: 913651188 Leonardo, en la National Gallery: DIreCCIÓN DE INTerNET: Historia de lo visible y lo invible http://www.alfayomega.es 30.000 personas ESPAÑA E-MAIL: sin hogar en España: [email protected] Hace 2012 años, Plan pastoral castrense: tampoco abrieron Un camino para ser fuertes en la fe. 18 DIreCTOR: las puertas al Niño Miguel Ángel Velasco Puente Reformas educativas: REDACTOR JEFE: Ricardo Benjumea de la Vega Es hora de hacer justicia DIreCTOR DE ARTE: a la clase de Religión 19 Francisco Flores Domínguez REDACTOreS: MUNDO Juan Luis Vázquez De la primavera árabe..., Díaz-Mayordomo (Jefe de sección), María Martínez López, a la marea islámica. 20 José Antonio Méndez Pérez, Benedicto XVI: La familia Cristina Sánchez Aguilar, Jesús Colina Díez (Roma) es el camino de la Iglesia 21 SECreTARÍA DE REDACCIÓN: LA VIDA 22-23 Cati Roa Gómez DOCUmeNTACIÓN: 24-25 DESDE LA FE María Pazos Carretero Sínodo de la Iglesia en Asturias: Irene Galindo López INTerNET: Germain Grisez, Un momento de gracia y respuesta. -

Léonard De Vinci (1452-1519)

1/44 Data Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) Pays : Italie Langue : Italien Sexe : Masculin Naissance : Anchiano (près de Vinci) (Italie), 15-04-1452 Mort : Amboise (Indre-et-Loire), 02-05-1519 Note : Peintre, sculpteur, architecte. - Théoricien de l'art. - Chercheur scientifique Domaines : Sciences Art Autres formes du nom : Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) (italien) Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) Da Vinci (1452-1519) Da Vinchi (1452-1519) (japonais) 30 30 30 30 30 30 C0 FB F4 A3 F3 C1 (1452-1519) (japonais) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0001 2124 423X (Informations sur l'ISNI) A dirigé : École de Léonard de Vinci Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) : œuvres (281 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres textuelles (152) Trattato della pittura (1651) Voir plus de documents de ce genre data.bnf.fr 2/44 Data Œuvres iconographiques (63) La Joconde nue Portrait de Christ : peinture parfois attribué à Léonard (1514) de Vinci (1452-1519) (1511) The Burlington House cartoon L'homme vitruvien (1500) (1492) La Vierge aux rochers : National gallery, Londres La Vierge aux rochers : Musée du Louvre (1491) (1483) Il Redentore La Belle princesse : dessin "Tête de vieillard maigre, les lèvres serrées" Codice Corazza de Anne Claude Philippe de Caylus avec Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) comme Dessinateur du modèle "Tête d'homme aux longs cheveux bouclés, coiffé d'une Codex atlanticus calotte" de Anne Claude Philippe de Caylus avec Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) comme Dessinateur du modèle "Buste d'un vieux moine" "Combat de divers animaux" de Anne -

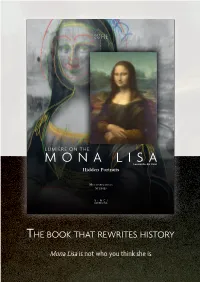

9782954825847.Pdf

Pascal c otte c Pascal otte he Mona Lisa is one of mankind’s great mysteries. With over 9.7 million admirers per year, it is the mostT mythical painting of all time. Thanks to an extraordinary sci- M l entific imagery technique (L.A.M.), this book takes us on a journey UMIÈR into the heart of the paint-layer of the world’s most famous pic- ture and reveals secrets that have remained hidden for 500 years. o e o Mona Lisa is not actually Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del N Giocondo, but a portrait that masks others. Leonardo da Vinci did N t not paint one, but four portraits, super-imposed on one another. H e More than 150 discoveries help us rediscover the painting’s gen- a esis, with Cotte reconstituting the true portrait of Lisa Gherardini – whose face, hairstyle and costume were radically different from those we now see in the Louvre. The book shatters the myth and l alters our vision of the work. It is a giant leap forward in art knowl- edge and art history. Pascal Cotte, who digitized the Mona Lisa at he book reveals that the Mona Lisa is not I the Louvre with his multispectral camera in October 2004, now Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, Leonardo da Vinci sa presents the fruit of ten years’ research. andT that her identity has been mistaken for 500 years. Using a new scientific imaging technique (L.A.M.), Cotte unveils over 150 dis- coveries found beneath all the repaintings. -

Text for the Leonardo Da Vinci Society

LA BELLA PRINCIPESSA and THE WARSAW SFORZIAD Circumstances of Rebinding and Excision of the Portrait Katarzyna Woźniak 10.05.2015 In the study titled La Bella Principessa and the Warsaw Sforziad, published in January 2011, Professor Kemp provided evidence that the portrait of Bianca Sforza was a part of an illuminated book printed on vellum - La Sforziada by Giovannni Simonetta, stored in the National Library in Warsaw1. The excision took place, most probably, during the process of rebinding. This was done meticulously, as his paper showed, although the knife slipped at near the bottom of the left edge2. At that moment, the portrait and the book were separated from each other and ceased to share the same fortune. 1. Images indicating that portrait of La Bella Principessa was part of a bound volume Author: Pascal Cotte My research initiated as a result of this discovery shows that the most probable date of rebinding of the Warsaw copy of La Sforziada was the turn of the 18th and 19th century3. The following text is an introduction to the first general analysis of the problems concerning 1 Martin Kemp and Pascal Cotte, La Bella Principessa and the Warsaw Sforziad (2010), The Leonardo da Vinci Society: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/hosted/leonardo/#MM 2 M. Kemp and P. Cotte, op. cit., p. 5 3 Extensive study of the history of the Zamoyski book collection as well as scrupulous analysis of alterations to the original volume – decoration of new leather cover, watermarks on inserted sheets, bookplates, existing and obliterated inscriptions - will be presented in the book published by the British publishing house Ashgate. -

Salvator Mundi Steven J. Frank ([email protected])

A Neural Network Looks at Leonardo’s(?) Salvator Mundi Steven J. Frank ([email protected]) and Andrea M. Frank ([email protected])1 Abstract: We use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to analyze authorship questions surrounding the works of Leonardo da Vinci in particular, Salvator Mundi, the world’s most expensive painting and among the most controversial. Trained on the works of an artist under study and visually comparable works of other artists, our system can identify likely forgeries and shed light on attribution controversies. Leonardo’s few extant paintings test the limits of our system and require corroborative techniques of testing and analysis. Introduction The paintings of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) represent a particularly challenging body of work for any attribution effort, human or computational. Exalted as the canonical Renaissance genius and polymath, Leonardo’s imagination and drafting skills brought extraordinary success to his many endeavors from painting, sculpture, and drawing to astronomy, botany, and engineering. His pursuit of perfection ensured the great quality, but also the small quantity, of his finished paintings. Experts have identified fewer than 20 attributable in whole or in large part to him. For the connoisseur or scholar, this narrow body of work severely restricts analysis based on signature stylistic expressions or working methods (Berenson, 1952). For automated analysis using data-hungry convolutional neural networks (CNNs), this paucity of images tests the limits of a “deep learning” methodology. Our approach to analysis is based on the concept of image entropy, which corresponds roughly to visual diversity. While simple geometric shapes have low image entropy, that of a typical painting is dramatically higher. -

Leonardo Da Vinci Art 485: Senior Seminar in Art History Wednesday Evenings 6:30-9:00

Prof. Victor Coonin Office Hours: M-F 10:45-11:30 412 Clough, x3824 and by appointment [email protected] Leonardo da Vinci Art 485: Senior Seminar in Art History Wednesday Evenings 6:30-9:00 Art 485 is a senior seminar designed for senior art history majors to examine the discipline of art history by concentrating on a focused topic. Emphasis is placed on critical reading and writing, analysis of art and critical methodology through class discussion, formal presentations, and a substantial research paper. Course Objectives and Description This course will introduce students to advanced critical methods of art history through an extensive examination of Leonardo da Vinci. Students will be introduced to the artist, and consider current debates, scholarly issues, and even the effect of the artist on popular culture. Students will fully engage with an extensive bibliography, intensive critical debates, and critical issues of iconography, connoisseurship, patronage, interpretation, and the contextualization of works of art. A crucial aspect of the course is to learn how art historians select objects and subjects for research, how they investigate works of art, and how they employ different methodologies in the course of critical analysis. Grading: Several Informal Presentations to be assigned weekly or bi-weekly (with brief summaries) Participation in discussions of readings and topics 1 Formal Presentation (20 minute PowerPoint presentation, followed by discussion with a critical audience) 1 research paper with full notes and bibliography based on the above Required Readings: Charles Nicholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Flights of the Mind, 2004 Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci, revised edition, 1989 Martin Kemp, Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man, revised, 2006 Martin Kemp, Leonardo, 2004 Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code, 2009 (Don’t confuse this with an academic reading) Other readings as assigned Schedule of Classes, Wednesdays: 6:30-9:00p.m. -

Salvator Mundi Salvator Mundi Book Review 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

July/Aug 19 galleys:November/Dec galley 18/6/19 10:29 Page 8 8 Book Review Salvator Mundi Salvator Mundi Book Review 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fig. 1: An etched copy of 1650 by Wenceslaus Hollar of a Salvator Mundi formerly (and erroneously) attributed to Leonardo in the collection SELLING A LEONARDO WITH ‘OOMPH’ of Charles I Fig. 2 : The photograph of the Salvator Mundi painting when in the Cook collection and judged to be a work of Bernardino Luini. Fig. 3 : the former Kuntz family and then Basil Clovis Hendry Sr. estate painting, as in the 2005 St. Charles Gallery catalogue. Fig. 4 : A screen share of the picture,’ Adelson says, ‘because I wanted to run with the grab of the Salvator Mundi as when taken, still sticky from a previous restoration in 2005 to Dianne Modestini’s New York studio. Fig. 5 : As The Last Leonardo – The secret lives of the ball and help them sell it.’ He negotiated a 33 per cent stake in the in 2007 in the newly released high-resolution photograph following cleaning and repairs to the panel but before any retouching, infilling or world’s most expensive painting painting in return for a $10 million advance payment. It was accepted. repainting. Will Modestini publish a photograph of the painting as presented to her in 2005? Fig. 6 : The Salvator Mundi as restored in 2008. As Robert Simon put it ‘there were a lot of expenses. The photography Fig. 7 : As in 2011 as exhibited as a Leonardo at the National Gallery, London, and after much repainting – some of which was distressed by Ben Lewis and the storage were expensive. -

Introduction Genius Pride Revenge Fame Crime Opportunism Money Power Conclusion

INTRODUCTION 10 THE WORLD WISHES TO BE DECEIVED … GENIUS 34 PRIDE 60 REVENGE 92 FAME 122 CRIME 148 OPPORTUNISM 166 MONEY 188 POWER 208 CONCLUSION 248 … SO LET IT BE DECEIVED NOTES 257 GLOSSARY OF SCIENTIFIC METHODS OF AUTHENTICATION 271 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 277 INDEX 285 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 291 01122014_Art of Forgery-AW.indd 4 02/12/2014 09:24 01122014_Art of Forgery-AW.indd 5 02/12/2014 09:24 THE WORLD WISHES TO BE DECEIVED… Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains! Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware! Know you not that I have a grant from the most glorious Emperor Maximilian that not one throughout the imperial dominion shall be allowed to print or sell fctitious imitations of these engravings? Listen! And bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger. – Albrecht Dürer This may well be the most belligerent property notice ever penned. It appeared in the colophon to an edition of an engraving series called Life of the Virgin¸ published in Nuremberg in 5. Its author and the creator of the engravings, the great painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer, had good reason to fear forgers. Dürer’s prints were wildly popular throughout Europe, highly collectible and a more affordable alternative to a painting. Dürer was perhaps the frst internationally self-promoting artist in history, more INTRODUCTION akin to Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst than the solitary, morose likes of contemporaries such as Giorgione or Pontormo. -

Leonardo 500 Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +44 (0) 1394 389950 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/uk Leonardo 500 Martin Kemp Fabio Scaletti ISBN 9788895847450 Publisher Scripta Maneant Editori Binding Hardback Size 335 mm x 250 mm Pages 304 Pages Illustrations 160 color, b&w Price £30.00 Published to coincide with the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci's death This volume represents an important tool for getting to know every aspect of Leonardo da Vinci's work: his pictorial technique, his scientific and technological investigation, his study on anatomy, his Codices, and every suggestion produced by his genius. All works and paintings are accompanied by descriptive and technical sheets, and ample space has been given to images and details, to the updated report on his most controversial works, to those of recent critical acceptance, and to the masterpieces that have animated the international debate such as The Encarnate Angel, the Salvator Mundi, and La Bella Principessa (Portrait of Bianca Sforza). The narrative captions reveal the most curious aspects of the history of each painting. Thanks to the direct contribution of collectors and museums the photographic reproductions of paintings and works reflect the last restorations. Text in English and French. Martin Kemp is Emeritus Professor of History of Art at the Oxford University and Member of the British Academy. He has curated several exhibitions dedicated to the work of Leonardo of whom he is one of the greatest international scholars. He has published several books and essays translated all over the world, and he has carried out the most extensive research on the painting La Bella Principessa by Leonardo. -

Leonardo Da Vinci Society Newsletter

Leonardo da Vinci Society Newsletter editor: Francis Ames-Lewis Issue 38, May 2012 Recent and forthcoming events talented lawyers Giasone del Maino and Franceschino Corte, masters of pageantry and The Annual General Meeting and Annual music Antonio Cornazzano, Josquin des Prez, and Lecture 2012 Gaspar van Weerbeke, poet/dramatists Gaspare Ambrogio Visconti and Galeotto del Carretto, not The AGM and Annual Lecture for 2012 were held to mention very close associates Donato as usual in the Kenneth Clark Lecture Theatre at Bramante, Bernardo Bellincioni, Francino the Courtauld Institute of Art, on Friday 27 April Gaffurio and Luca Pacioli. Though relatively little 2012. The Annual Lecture was given by Dr is known of Leonardo’s direct engagement with Matthew Landrus, whose title was ‘New Evidence most of these individuals, he regularly requested of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper as a advice and information on a broad range of Humanist Contribution’. projects. For two of the most celebrated aspects of Dr Matthew Landrus writes: Although one the Last Supper – the naturalistic ‘truth’ of the sees Leonardo’s approaches to humanist figural emotions and the fictive space – he scholarship throughout his notebooks, and referenced Latin scholarship, as well as the Latin especially in his notes for a comparison of the arts tradition in painting that extended from Giotto (his paragone), direct humanistic engagements in and Masaccio. Referring to the ‘strife’ discussed his paintings are relatively unconfirmed when one in Luke 22: 21-24, Leonardo presents contrasts in considers his modes of musical and dramaturgical movements of the mind similar to what one reads engagement.