The Southern Hebron Hills: Susiya, Eshtemoa, Maʻon (In Judea), and Ḥ. ʻanim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Springs of Gush Etzion Nature Reserve Nachal

What are Aqueducts? by the Dagan Hill through a shaft tunnel some 400 meters long. In addition to the two can see parts of the “Arub Aqueduct”, the ancient monastery of Dir al Banat (Daughters’ settlement was destroyed during the Bar Kochba revolt. The large winepress tells of around. The spring was renovated in memory of Yitzhak Weinstock, a resident of WATER OF GUSH ETZION From the very beginning, Jerusalem’s existence hinged on its ability to provide water aqueducts coming from the south, Solomon’s pools received rainwater that had been Monastery) located near the altered streambed, and reach the ancient dam at the foot THE SPRINGS OF GUSH ETZION settlement here during Byzantine times. After visiting Hirbat Hillel, continue on the path Alon Shvut, murdered on the eve of his induction into the IDF in 1993. After visiting from which you \turned right, and a few meters later turn right again, leading to the Ein Sejma, descend to the path below and turn left until reaching Dubak’s pool. Built A hike along the aqueducts in the "Pirim" (Shafts) for its residents. Indeed, during the Middle Canaanite period (17th century BCE), when gathered in the nearby valley as well as the water from four springs running at the sides of the British dam. On top of the British dam is a road climbing from the valley eastwards Start: Bat Ayin Israel Trail maps: Map #9 perimeter road around the community of Bat Ayin. Some 200 meters ahead is the Ein in memory of Dov (Dubak) Weinstock (Yitzhak’s father) Dubak was one of the first Jerusalem first became a city, its rulers had to contend with this problem. -

Imagining the Border

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1. -

Ngo Documents 2013-11-01 00:00:00 Financing the Israeli Occupation the Current Involvement Of

Financing the Israeli Occupation The Current Involvement of Israeli Banks in Israeli Settlement Activity Flash Report November 2013 In October 2010, Who Profits published a report about the Israeli banks' involvement in the Israeli occupation. The Israeli banks provide the financial infrastructure for activities of companies, governmental agencies and individuals in the occupied Palestinian territories and the Syrian Golan Heights. Who Profits' research identified six categories in which Israeli banks are involved in the occupation: providing mortgage loans for homebuyers in settlements; providing financial services to settlements' local authorities; providing special loans for construction projects in settlements; operating branches in Israeli settlements; providing financial services to businesses in settlements; and benefiting from access to the Palestinian monetary market as a captured market. Additionally, as Who Profits' report shows, it is evident that the banks are well aware of the types and whereabouts of the activity that is being carried out with their financial assistance. Our new flash report reveals that all the Israeli banks are still heavily involved in financing Israeli settlements, providing services to settlements and financially supporting construction project on occupied land. Contents: Dexia Israel .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Hapoalim Bank ................................................................................................................................... -

Judea and Samaria

4 Cities, 6 Regional councils, 13 Local Councils, 150 Communities populated by 360,000 Israelis living in Judea & Samaria, spread out on 21% of all territories west of the Jordan River The communities use 3% of Judea & Samaria’s land in the mountains and the valleys, with 48,000 dunams (12,000 acres) used for Jewish IT'S REALISTIC IT'S agriculture, including vineyards, olive groves, fields for | organic vegetables and rare flowers The mountains of Judea & Samaria reach an altitude of 3,060 feet above sea level and under them lies the largest reservoir of fresh water in Israel – the Mountain Aquifer, which is divided into three basins that supply the State of Israel IT'S VITAL with 50% of its water needs In Judea & Samaria, | there are 20 national parks and nature reserves which draw 1,000,000 visitors per year 80% of the historic events of the Bible occurred in Judea & Samaria, which today has 45 holy sites and tombs of the righteous 17,000 workers are employed by the industries and agriculture of the area, including 11,000 Arabs There are over 800 workplaces spread throughout 14 IT'S JEWISH industrial and agricultural centers in Judea & Samaria. Judea & Samaria It's Time to Get Acquainted www. efshari. co. il ½Ä´ ´·Ä °¬¼´´¿¬½ Ä´ÅÁ½°¹ ´·Ä½Ä´ מועצת COUNCIL יש"עÄ´ÅÁ½°¹ THE YESHA °¬¼´´¿¬½ JUDEA AND SAMARIA AND JUDEA JUDEA AND SAMARIA IT'S JEWISH | IT'S VITAL | IT'S REALISTIC The YESHA Council - The Jewish Communities of Judea Samaria and Gush Katif 55 Ramat Hagolan St., Jerusalem, Israel • Tel. -

Sara Yael Hirschhorn – Excerpt from Dissertation Chapter Three: Efrat – Copyright 2011 – Do Not Circulate

Sara Yael Hirschhorn – Excerpt From Dissertation Chapter Three: Efrat – Copyright 2011 – Do Not Circulate Raishit Geula: Rabbi Shlomo Riskin’s Jewish-American Garin and the Makings of Efrat, 1973-1987 Efrat, named for the biblical locale mentioned in the Book of Chronicles, is located in the Gush Etzion region of the West Bank between Bethlehem and Hebron. With a population of over seven thousand residents, of which approximately half are American-Israelis, the city is the most highly recognizable Jewish-American colony in the occupied territories and has emerged as the cornerstone of the Etzion bloc.1 Yet, how did Efrat rise from the rubble of the post-1973 war to become the incipient American-style ―capital of the Gush‖2 in less than a decade? The story of Efrat is one of a strategic partnership between Israeli settlers and Jewish- American immigrants after the Yom Kippur War. It is framed by the personal friendship and professional partnership between Moshe Moshkowitz, a son of the pre-1948 Gush Etzion settlements and the New York –based modern Orthodox rabbi Steven (Shlomo) Riskin, which combined the insider knowledge and connections of a native activist with the capital and manpower galvanized by a dynamic spiritual leader. Efrat also produced a new model for American-Israeli settlement in the West Bank that combined the efforts an Israeli non- governmental organization, the Judean Hills Development Co., alongside Garin Raishit Geula [lit. The Origins of Redemption] in the United States. This cooperative venture and division of labor allowed Efrat to deftly navigate the politics and pitfalls of local coordination with the Israeli government while still retaining the distinctly American character of its new township. -

Alon Shvut Process of Building) and Continue to Claim That Attesting to the Healthy and Strong Jewish Spirit That 30,000 of Whom Were Jews

SOVEREIGNTY A Political Journal / Issue no. 2 / Shevat 5774 / January 2014 Published by Women in Green and the Forum for Sovereignty The Zionist We must not allow international pressure to cause us to neglect the best, most realistic Alternative and Zionist political plan for Israel The Jordan Valley Deputy Minister Coalition Head Caroline Glick: Mayor Gershon Mesika: Yoram Ettinger: Tzipi Hotovely: MK Yariv Levin: The Israeli solution– The application of The Jewish fertility rate The goal - Judea Prepare the legal a One-State plan sovereignty is a is rising impressively, and Samaria under ground for application for peace in fundamental especially among Israeli sovereignty of sovereignty the Middle East ideological goal secular people 4 7 8 6 12 2 / SOVEREIGNTY / Political Journal Political Journal / SOVEREIGNTY / 3 Content Letters to the Editor Coalition Chairman Yariv Levin Deputy Minister Tzipi Hotovely Mayor Gershon Mesika Prepare the constitutional ground The gradual plan – Blasts of 7 for the application of sovereignty ‘Annexation-Naturalization' consciousness Caroline Glick 4 6 Explaining the Right’s 8 alternative to the world A Word from the Editors We are Jews – from our Office of Foreign of Affairs that a complaint that there are Conventions of 1864, 1906, 1926 and because we came from Judea was ever registered to Israel regarding this miserable 1949. It is the Convention of 1949 which applies. In affair. If any piece of shrapnel hits an Arab youth on this Convention, there are four major components. Ambassador (ret.) Yoram Ettinger To the editor: his great toe, there would be a huge uproar and there The applicable component is Part IV, "Protection of Demography works The second issue of “Sovereignty” was prepared nevertheless, this is not enough. -

Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia Couples' Mission to Israel

Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia Couples’ Mission to Israel October 26-November 2, 2019 SUBJECT TO CHANGE Saturday, October 26th-Welcome to Israel • Mid-afternoon arrival TBA at Israel’s Ben Gurion international airport. You will be met by your guide and escorted as VIPs to awaiting transportation. • Transfer to Jerusalem. • Participate in Havdallah ceremonies overlooking the Old City. • Dinner at the hotel. Overnight: David Citadel Hotel, Jerusalem Sunday, October 27th-Visions of Jerusalem • Over breakfast, meet with Arielle Di Porto, the Director of Aliyah Services for an in-depth, VIP briefing of the Jewish Agency’s work in the Middle East (subject to availability). • Embark on a tour of the City of David accompanied by an archaeologist. See ongoing archaeological excavations with special access to normally restricted areas. • Go for a short walking tour of the Old City, including some free time for shopping. • Lunch on own in the Jewish Quarter. • Visit the command center of Mabat 2000 and meet with the officers of the Israel Police, who maintain and operate one of Israel's most sophisticated network of urban surveillance cameras (subject to availability). • Visit the JAFI Ketzev-supported Mashu Mashu Theater Company for Social Change, located in Jerusalem’s peripheral Kiryat Yovel neighborhood. Enjoy fun and thought-provoking theater exercises in the ‘Theater and Social Change workshop’ OR take a tour of the neighborhood to see Mashu Mashu’s art initiatives: An amphitheater in a formerly abandoned park, a bomb shelter converted into an art studio and an outdoor gallery. • In the evening, have dinner at Anna, joined by Alon Ben David (subject to availability). -

Prominent Israeli Violations in the Palestinian Territories Till the First Half of 2017

Prominent Israeli Violations in The Palestinian Territories till The First Half of 2017 July 7102 1 Executive summary In the first half of 2017 The Israeli occupying power has continued and escalated the polices of investing in and encouraging colonial settlement in the State of Palestine on the one hand, while discouraging sustainability and development for Palestinian communities on the other. The report also details Government Provided Economic Incenitives for Colonial Settlers describing the effects of these policy in increasing “Judiazation” of certain areas and the forced displacement of their Palestinian residents. This report covers actions taken by the occupying power for this purpose using various methods such as: Government decisions, laws, bills, the provision of economic incentives for colonial settlers as well as fragmentation, demolitions and confiscation of Palestinian land and property. The report describes the following actions taken from the 1st of January to the 30th of June 2017; Thirteen government decisions taken by The 34th Israeli government led by Binyamin Netanyahu expanding and cementing the annexation of Occupied East Jerusalem and the de-facto annexation of Area C. Three Laws passed by the Israeli parliament and nine bills directly aimed at cementing the colonial project in the Occupied State of Palestine, six of these Bills propose to officially annex more of the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Over 121 master plans authorizing the construction of over 11,311 residential units plans were processed for approval in planning committees of the civil administration and the Jerusalem regional and municipal committees. This number exceeds the number of residential units processed for approval in all of 2016. -

Israeli Annexation

BADIL ISRAELI ANNEXATION: ISRAELI ANNEXATION: The Case of ETZION COLONIAL BLOC Israeli Annexation Israeli : The Case of : The Case of BADIL بـديـــــل Resource Center المركز الفلسطيني for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights BLOC لمصـادر OLONIALحقـوق المواطنـة C والـالجئيـنIn conclusion, the manageable realization of de jure annexation is inextricably ETZION Etzion Colonial Bloc Colonial Etzion tied to the establishment of an apartheid state that can dominate and isolate the BADIL has consultative status with UN ECOSOC Palestinian population. In other words, under the guise of occupation, Israel has clearly achieved de facto annexation of large areas, and is evolving its strategy into creeping de jure annexation, underpinned by apartheid. With Israel’s effective control over the occupied territory, the urgency for third party states to act and fulfil their obligations has never been more demanding. The question BADIL بـديـــــل thus remains of how long and intensely Israel will continue its annexation Resource Center املركز الفلسطيني attempts and apartheid rule of a steadfast and perseverant Palestinian people for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights ملصـادر حقـــوق املواطنـة والـالجئيـن before duty bearers intervene to fulfill their obligations to uphold the rights of BADIL has consultative status with UN ECOSOC the Palestinian people in accordance with international law. July 2019 July 2019 Lead Researcher: Melissa Yvonne Editor: Lubnah Shomali Desk Researchers: Amaya al-Orzza, Alice Osbourne, Martina Ramacciotti, Shaina Rose -

Parashat Parah As We Welcome Oded Revivi, Phyllis Newsome, Bookkeeper: Mayor of Efrat

Hebrew Institute of Riverdale Bayit BULLETIN March 29 - April 5, 2019 22 Adar II - 29 Adar II, 5779 3700 Henry Hudson Parkway, Bronx, NY 10463 718-796-4730 www.thebayit.org Steven Exler, Senior Rabbi: Mazal Tov to: [email protected]/ x108 Anat Sharbat, Ph.D., Associate Rabba: Aimee & Jonathan Baron on the bar mitzvah of their son, Doniel. To siblings Leah, Yael, [email protected]/ x106 Avital and Netanel, honored grandparents Elliott & Sabina Friedman and Joan & Reuben Ezra Seligsohn, Associate Rabbi: Baron. [email protected]/ x219 Sara Hurwitz, Rabba: Alisa & Michael Brown on the birth of a grandchild. [email protected]/ x107 Michellle Biller-Levy & Orrie Levy on the birth of a boy. To siblings Noam & Amalia as well. Avi Weiss, Rabbi in Residence: [email protected]/ x102 Steven Katchen and Shira Zeif on their engagement. To Shira’s parents Susan & Bob Zeif and Richard Langer, Executive Director: Steven’s parents Alice & Hazzan David Katchen and Steven’s children Rafi and Micah.. [email protected]/ x104 Eitan Cooper, Co-Youth Director: Welcome to new members: Beth & Yashi Kraus [email protected]/ x240 Emily Hausman, Co-Youth Director: THIS SHABBAT @ THE BAYIT [email protected]/ x120 Bryan Cordova, Facilities Manager: SPECIAL GUEST: ODED REVIVI - SHABBAT, MARCH 30TH [email protected]/ x121 Please join us on Shabbat Parashat Parah as we welcome Oded Revivi, Phyllis Newsome, Bookkeeper: Mayor of Efrat. [email protected]/ x103 Yael Oshinsky, Program Associate: Oded Revivi, Mayor of Efrat and Chief Foreign Envoy – YESHA Council [email protected]/ x116 (Council of Jewish Settlements in Judea and Samaria), is a statesman, orator, lawyer, mayor Shuli Boxer Rieser, Assistant to R’ Weiss: and prominent advocate for the Israeli communities in Judea and Samaria. -

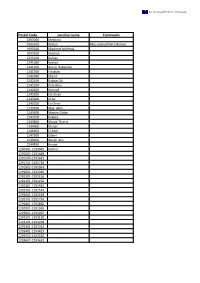

Postal Code Locality Name Comments

Postal Code Locality name Comments 1093000 Mechola 1093100 Rotem Also named Nahal Rotem 1093200 Shadmot Mechola 1093500 Maskiot 1225100 Banias 1241000 Keshet 1241200 Alonei Habashan 1241500 Yonatan 1242000 Sha'al 1242100 Kidmat Zvi 1242200 Kela Alon 1242400 Nimrod 1242600 Ein-Zivan 1243000 Ortal 1243200 Ein Kinia 1243500 Mas' adeh 1243600 Merom Golan 1243700 Bukata 1243800 Majdal Shams 1244000 Ghajar 1246600 El-Rom 1247300 Odem 1249300 Neveh Ativ 1249500 Aniam 1290101-1290945 Katzrin 1291001-1291448 1291504-1291642 1291701-1291739 1291802-1291954 1292001-1292040 1292101-1292156 1292201-1292256 1292301-1292462 1292501-1292542 1292601-1292638 1292701-1292730 1292801-1292860 1292901-1292926 1293001-1293065 1293101-1293130 1293201-1293208 1293301-1293352 1293401-1293423 1293502-1293550 1293601-1293632 1293701-1293767 1293802-1293920 1294001-1294156 1294201-1294342 1294402-1294575 1294601-1294728 1294801-1294835 1291500 Natur 1291700 Ramat Magshimim 1292000 Hispin 1292100 Nov 1292500 Avnei Eitan 1292700 Eli'ad 1293000 Kanaf 1293200 Kfar Haruv 1293400 Mevo Hama 1293600 Metzar 1293800 Afik 1294000 Ne'ot Golan 1294200 Gshur 1294400 Bnei Yehuda 1294600 Givat Yoav 1294800 Ramot 1294900 Ma'aleh Gamla 1295000 Had-Nes 1290503 Ta'asiot Golan A factory 3786200 Shaked 3786700 Hinanit 3787000 Rehan 4070202-4079316 Ariel 4481000 Sha'arei Tikva 4481300 Oranit 4481400 Elkana 4481500 Kiryat Netafim 4481600 Etz Efraim 4482000 Barkan 4482100 Barkan I.Z. 4482500 Ma'aleh Levonah 4482700 Rehelim 4482800 Eli 4482900 Kfar Tapuach 4483000 Shilo 4483100 Yitzhar 4483200 Shvut Rachel 4483300 Elon Moreh 4483400 Itamar 4483500 Bracha 4483900 Revava 4484100 Nofim 4484300 Yakir 4484500 Emanu'el 4485100 Alfei Menasheh 4485200 Ma'aleh Shomron 4485500 Karnei Shomron 4485600 Kdumim 4485700 Enav 4485800 Shavei Shomron 4486100 Avnei Hefetz 4486500 Zufim 4489000 Mevo Dotan 4489500 Hermesh 4584800 Nitzanei Shalom I.Z. -

Of 19 a List of Companies Targeted for Divestment by Institutional Investors Around the World Due to Their Complicity In

A list of companies targeted for divestment by institutional investors around the world due to their complicity in severe violations of human rights and international law in the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands and in the attacks on Gaza. Companies traded in the United States: THE BOEING COMPANY The Boeing Company is a multinational arms manufacturer headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. In 2012, it was listed as the second largest arms supplier in the world. The company has provided Israel with AH-64 Apache helicopters, F-15 Eagle fighter jets, Hellfire missiles (produced with Lockheed Martin), as well as MK84 2000-lb bombs, Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM) kits that turn bombs into “smart,” guided bombs, and the Harpoon sea- to-sea missile system. The Israeli Air Force uses various other Boeing aircraft for transport and refueling, and is anticipating the delivery of Bell Boeing V-22 aircraft. Boeing has long-term cooperation agreements with the Israeli weapons industry that include the development of the Arrow anti-ballistic missile system (with Israel Aerospace Industries) and the marketing in the US of the Israeli UAV military drones Hermes 450 and 900. Apache helicopters and Hellfire missile-equipped drones are the primary tools used by Israel for attacks on urban Palestinian areas and “targeted assassinations.” Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and United Nations commissions have reported the repeated and regular use of weapons in human rights violations and war crimes committed by the Israeli military in Lebanon, the West Bank, and Gaza. According to the UN’s Fact-Finding Mission to the Gaza Conflict, missiles fired from Apache helicopters targeted civilians during Operation Cast Lead in Gaza in 2008-9.