DRAFT LAND GRAB Israel's Settlement Policy in the West Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At the Supreme Court Sitting As the High Court of Justice

Disclaimer: The following is a non-binding translation of the original Hebrew document. It is provided by HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual for information purposes only. The original Hebrew prevails in any case of discrepancy. While every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy, HaMoked is not liable for the proper and complete translation nor does it accept any liability for the use of, reliance on, or for any errors or misunderstandings that may derive from the English translation. For queries about the translation please contact [email protected] At the Supreme Court HCJ 5839/15 Sitting as the High Court of Justice HCJ 5844/15 1. _________ Sidr 2. _________ Tamimi 3. _________ Al Atrash 4. _________ Tamimi 5. _________ A-Qanibi 6. _________ Taha 7. _________ Al Atrash 8. _________ Taha 9. HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte Salzberger - RA Represented by counsel, Adv. Andre Rosenthal 15 Salah a-Din St., Jerusalem Tel: 6250458, Fax: 6221148; cellular: 050-5910847 The Petitioners in HCJ 5839/15 1. Anonymous 2. Anonymous 3. Anonymous 4. HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte Salzberger – RA Represented by counsel, Adv. Michal Pomeranz et al. 10 Huberman St. Tel Aviv-Jaffa 6407509 Tel: 03-5619666; Fax: 03-6868594 The Petitioners in HCJ 5844/15 v. Military Commander of the West Bank Area Represented by the State Attorney's Office Ministry of Justice, Jerusalem Tel: 02-6466008; Fax: 02-6467011 The Respondent in HCJ 5839/15 1. Military Commander of the West Bank Area 2. -

The Good Samaritan Inn 55 NATIONAL PARKS and NATURE Mosaic Museum RESERVES

BUY AN ISRAEL NATURE AND PARKS AUTHORITY SUBSCRIPTION FOR UNLIMITED FREE ENTRY TO The Good Samaritan Inn 55 NATIONAL PARKS AND NATURE Mosaic Museum RESERVES. A lioness from the Gaza mosaic Rules of Conduct ■ Do not harm the antiquities: Do not carve on them, walk on them or pour water on them. ■ Do not collect “souvenirs” from remains scattered in the area. ■ Do not enter places that are off-limits for visitors. Nearby Sites: ■ Do not cross fences or roll stones. ■ Please keep the area clean. Qumran Location of the Good Samaritan Inn Mosaic Museum National Park about 25 minutes’ drive The museum is on the southern side of the Jerusalem–Jericho road (road 1) between kilometer markers 80 and 81. The interchange affords easy access from whichever direction you approach. To reserve a guided tour for a group, email: You Enot Tsukim are here Nature Reserve [email protected] about 25 minutes’ drive Hours: Daily from 8:00 to 17:00. En Prat During winter time, the site closes one hour earlier. Nature Reserve On Fridays and holiday eves, the site closes one hour earlier. about 20 minutes’ drive Entry is permitted up to one hour before closing. Text: Ya‘acov Shkolnik Translation: Miriam Feinberg Vamosh 6.18 Photos: Israel Nature and Parks Authority Archive; Ya‘acov Shkolnik; Tal Romano; Amir Aloni Production: Adi Greenbaum www.parks.org.il I *3639 I © Israel Nature and Parks Authority The Good Samaritan Inn, Tel: 02-6338230 established on the initiative of the archaeologist Dr. Yitzhak Welcome to the Magen, who served as the head of the Judea and Samaria Inn of the Good Samaritan Archaeology Unit. -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 28N FebruaryS – 6 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 28 February – 6 March 2007 Of note this week The IDF imposed a total closure on the West Bank during the Jewish holiday of Purim between 2 – 5 March. The closure prevented Palestinians, including workers, with valid permits, from accessing East Jerusalem and Israel during the four days. It is a year – the start of the 2006 Purim holiday – since Palestinian workers from the Gaza Strip have been prevented from accessing jobs in Israel. West Bank: − On 28 February, the IDF re-entered Nablus for one day to continue its largest scale operation for three years, codenamed ‘Hot Winter’. This second phase of the operation again saw a curfew imposed on the Old City, the occupation of schools and homes and house-to-house searches. The IDF also surrounded the three major hospitals in the area and checked all Palestinians entering and leaving. According to the Nablus Municipality 284 shops were damaged during the course of the operation. − Israeli Security Forces were on high alert in and around the Old city of Jerusalem in anticipation of further demonstrations and clashes following Friday Prayers at Al Aqsa mosque. Due to the Jewish holiday of Purim over the weekend, the Israeli authorities declared a blanket closure from Friday 2 March until the morning of Tuesday 6 March and all major roads leading to the Old City were blocked. -

The Changing Forms of Incitement to Terror and Violence

THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT TO TERROR AND VIOLENCE: TERROR AND TO THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT The most neglected yet critical component of international terror is the element of incitement. Incitement is the medium through which the ideology of terror actually materializes into the act of terror itself. But if indeed incitement is so obviously and clearly a central component of terrorism, the question remains: why does the international community in general, and international law in particular, not posit a crime of incitement to terror? Is there no clear dividing line between incitement to terror and the fundamental right to freedom of speech? With such questions in mind, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung held an international conference on incitement. This volume presents the insights of the experts who took part, along with a Draft International Convention to Combat Incitement to Terror and Violence that is intended for presentation to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The Need for a New International Response International a New for Need The THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT TO TERROR AND VIOLENCE: The Need for a New International Response Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT TO TERROR AND VIOLENCE: The Need for a New International Response Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( This volume is based on a conference on “Incitement to Terror and Violence: New Challenges, New Responses” under the auspices of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, held on November 8, 2011, at the David Citadel Hotel, Jerusalem. -

Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy

Order Code RL33530 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy Updated August 4, 2006 Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy Summary After the first Gulf war, in 1991, a new peace process involved bilateral negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. On September 13, 1993, Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) signed a Declaration of Principles (DOP), providing for Palestinian empowerment and some territorial control. On October 26, 1994, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and King Hussein of Jordan signed a peace treaty. Israel and the Palestinians signed an Interim Self-Rule in the West Bank or Oslo II accord on September 28, 1995, which led to the formation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) to govern the West Bank and Gaza. The Palestinians and Israelis signed additional incremental accords in 1997, 1998, and 1999. Israeli-Syrian negotiations were intermittent and difficult, and were postponed indefinitely in 2000. On May 24, 2000, Israel unilaterally withdrew from south Lebanon after unsuccessful negotiations. From July 11 to 24, 2000, President Clinton held a summit with Israeli and Palestinian leaders at Camp David on final status issues, but they did not produce an accord. A Palestinian uprising or intifadah began that September. On February 6, 2001, Ariel Sharon was elected Prime Minister of Israel, and rejected steps taken at Camp David and afterwards. The post 9/11 war on terrorism prompted renewed U.S. -

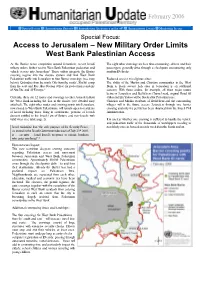

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

The Economic Base of Israel's Colonial Settlements in the West Bank

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Economic Base of Israel’s Colonial Settlements in the West Bank Nu’man Kanafani Ziad Ghaith 2012 The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Promoting knowledge-based policy formulation by conducting economic and social policy research in accordance with the expressed priorities and needs of decision-makers. Evaluating economic and social policies and their impact at different levels for correction and review of existing policies. Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Mohammad Mustafa, Nabeel Kassis, Radwan Shaban, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Samir Abdullah (Director General). Copyright © 2012 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. -

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

99.8% of State Lands Allocated in the West Bank Were Given to Israelis; Palestinians Were Given Almost Nothing

State Land Allocation in the West Bank—For Israelis Only, July 2018 99.8% of state lands allocated in the West Bank were given to Israelis; Palestinians were given almost nothing Following a request under the Freedom of Information Act submitted by Peace Now and the Movement for Freedom of Information (and after refusing to give the information and a two-and-a-half year delay), the Civil Administration's response was received: 99.76% (about 674,459 dunams) of state land allocated for any use in the Occupied West Bank was allocated for the needs of Israeli settlements. The Palestinians were allocated, at most, only 0.24% (about 1,625 dunams). Some 80% of the allocations to Palestinians (1,299 dunams) were for the purpose of establishing settlements (669 dunams) and for the forced transfer of Bedouin communities (630 dunams). Only 326 dunams at most were allocated without strings for the benefit of Palestinians, and at least 121 of those dunams are currently in Area B under Palestinian control. Most of the allocations to the Palestinians (about 53%) were made prior to the 1995 Interim Agreement (the Oslo II Agreement, in which the West Bank was divided into Areas A, B and C, and transferred control over 40% of the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority). The High Court of Justice is currently facing the issue of the evacuation of the Palestinian village of Al-Khan al- Ahmar, which the state wants to demolish and expel its residents to another area. The residents of the village are asking the High Court of Justice to stop the evacuation until the Civil Administration discusses the detailed construction plan they prepared for the village's approval, which the state has refused to consider. -

The Springs of Gush Etzion Nature Reserve Nachal

What are Aqueducts? by the Dagan Hill through a shaft tunnel some 400 meters long. In addition to the two can see parts of the “Arub Aqueduct”, the ancient monastery of Dir al Banat (Daughters’ settlement was destroyed during the Bar Kochba revolt. The large winepress tells of around. The spring was renovated in memory of Yitzhak Weinstock, a resident of WATER OF GUSH ETZION From the very beginning, Jerusalem’s existence hinged on its ability to provide water aqueducts coming from the south, Solomon’s pools received rainwater that had been Monastery) located near the altered streambed, and reach the ancient dam at the foot THE SPRINGS OF GUSH ETZION settlement here during Byzantine times. After visiting Hirbat Hillel, continue on the path Alon Shvut, murdered on the eve of his induction into the IDF in 1993. After visiting from which you \turned right, and a few meters later turn right again, leading to the Ein Sejma, descend to the path below and turn left until reaching Dubak’s pool. Built A hike along the aqueducts in the "Pirim" (Shafts) for its residents. Indeed, during the Middle Canaanite period (17th century BCE), when gathered in the nearby valley as well as the water from four springs running at the sides of the British dam. On top of the British dam is a road climbing from the valley eastwards Start: Bat Ayin Israel Trail maps: Map #9 perimeter road around the community of Bat Ayin. Some 200 meters ahead is the Ein in memory of Dov (Dubak) Weinstock (Yitzhak’s father) Dubak was one of the first Jerusalem first became a city, its rulers had to contend with this problem.