Designing Silverlight® Business Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workspace Desktop Edition Developer's Guide

Workspace Desktop Edition Developer's Guide Best Practices for Views 10/3/2021 Contents • 1 Best Practices for Views • 1.1 Keyboard Navigation • 1.2 Branding • 1.3 Localization • 1.4 Parameterization • 1.5 Internationalization • 1.6 Screen Reader Compatibility • 1.7 Themes • 1.8 Loosely-coupled Application Library and Standard Controls • 1.9 Views Workspace Desktop Edition Developer's Guide 2 Best Practices for Views Best Practices for Views Purpose: To provide a set of recommendations that are required in order to implement a typical view within Workspace Desktop Edition. Workspace Desktop Edition Developer's Guide 3 Best Practices for Views Keyboard Navigation TAB Key--Every control in a window has the ability to have focus. Use the TAB key to move from one control to the next, or use SHIFT+TAB to move the previous control. The TAB order is determined by the order in which the controls are defined in the Extensible Application Markup Language (XAML) page. Access Keys--A labeled control can obtain focus by pressing the ALT key and then typing the control's associated letter (label). To add this functionality, include an underscore character (_) in the content of a control. See the following sample XAML file: [XAML] <Label Content="_AcctNumber" /> Focus can also be given to a specific GUI control by typing a single character. Use the WPF control AccessText (the counterpart of the TextBlock control) to modify your application for this functionality. For example, you can use the code in the following XAML sample to eliminate having to press the ALT key: [XAML] <AccessText Text="_AcctNumber" /> Shortcut Keys--Trigger a command by typing a key combination on the keyboard. -

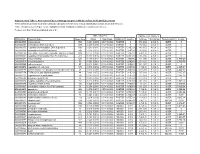

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

(RUNTIME) a Salud Total

Windows 7 Developer Guide Published October 2008 For more information, press only: Rapid Response Team Waggener Edstrom Worldwide (503) 443-7070 [email protected] Downloaded from www.WillyDev.NET The information contained in this document represents the current view of Microsoft Corp. on the issues discussed as of the date of publication. Because Microsoft must respond to changing market conditions, it should not be interpreted to be a commitment on the part of Microsoft, and Microsoft cannot guarantee the accuracy of any information presented after the date of publication. This guide is for informational purposes only. MICROSOFT MAKES NO WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IN THIS SUMMARY. Complying with all applicable copyright laws is the responsibility of the user. Without limiting the rights under copyright, no part of this document may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), or for any purpose, without the express written permission of Microsoft. Microsoft may have patents, patent applications, trademarks, copyrights or other intellectual property rights covering subject matter in this document. Except as expressly provided in any written license agreement from Microsoft, the furnishing of this document does not give you any license to these patents, trademarks, copyrights, or other intellectual property. Unless otherwise noted, the example companies, organizations, products, domain names, e-mail addresses, logos, people, places and events depicted herein are fictitious, and no association with any real company, organization, product, domain name, e-mail address, logo, person, place or event is intended or should be inferred. -

Automation Anywhere Version A2019.14 On-Premises Automation Anywhere - Contents

07/09/2020 Automation Anywhere Version A2019.14 On-Premises Automation Anywhere - Contents Contents Explore.......................................................................................................................................................................................7 Enterprise A2019 Release Notes...........................................................................................................................8 Enterprise A2019.14 Release Notes.........................................................................................................8 Enterprise A2019.13 Release Notes.......................................................................................................22 Enterprise A2019.12 Release Notes.......................................................................................................33 Enterprise A2019.11 Release Notes....................................................................................................... 45 Enterprise A2019.10 Release Notes.......................................................................................................55 Enterprise Version A2019 (Build 2094) Release Notes.................................................................... 62 Enterprise Version A2019 (Builds 1598 and 1610) Release Notes.................................................68 Enterprise Version A2019 (Builds 1082 and 1089) Release Notes................................................ 74 Enterprise A2019 (Build 550) Release Notes......................................................................................80 -

Silk Test 19.5

Silk Test 19.5 Silk4NET User Guide Micro Focus The Lawn 22-30 Old Bath Road Newbury, Berkshire RG14 1QN UK http://www.microfocus.com Copyright © Micro Focus 1992-2018. All rights reserved. MICRO FOCUS, the Micro Focus logo and Silk Test are trademarks or registered trademarks of Micro Focus IP Development Limited or its subsidiaries or affiliated companies in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. All other marks are the property of their respective owners. 2018-10-23 ii Contents Licensing Information ........................................................................................9 Silk4NET ............................................................................................................10 Do I Need Administrator Privileges to Run Silk4NET? ......................................................10 Automation Under Special Conditions (Missing Peripherals) ............................................10 Silk Test Product Suite ...................................................................................................... 12 Enabling or Disabling Usage Data Collection ....................................................................13 Contacting Micro Focus .................................................................................................... 14 Information Needed by Micro Focus SupportLine .................................................. 14 What's New in Silk4NET ...................................................................................15 UI Automation Support ......................................................................................................15 -

4. Empty Folders This Report Gives an Overview of All the Empty Folder and a List of Their Locations

File share analysis reports Introduction It is hard to find an organization that is not still using file shares. Nowadays, file shares are outdated, have high costs to maintain, create chaos due to the immense numbers of copies of files and insufficient ways of structuring them, and risk exposure is significant. Do you finally want to order this chaos and solve the problems it brings? Xillio file share analysis Xillio can perform extensive file share analysis, and generate reports in a very short time frame. You can run this process through your preferred systems integrator, or just let Xillio do the work. The analysis lets you understand which content on your file shares is redundant, obsolete and trivial. Or, gives insight in what content is located on your files shares in general. The Xillio file share analysis package includes a number of pre-built reports and analyses. This data is all captured using the delivered scripts and robots and stored in a database for easy access and reporting. This data may be further exported to Excel or integrated with another Business Intelligence tool of choice for further analysis. In this document Xillio explains the delivery of the file share analysis. Each report gives different insights, examples of which are also given in this document. These insights are not extensive, there are many other variations of these which can be produced to create your own new insights. To guide you through this process, for each report the most used insights that you can get out of it, is described. Report examples 1. -

Forcepoint DLP Supported File Formats and Size Limits

Forcepoint DLP Supported File Formats and Size Limits Supported File Formats and Size Limits | Forcepoint DLP | v8.8.1 This article provides a list of the file formats that can be analyzed by Forcepoint DLP, file formats from which content and meta data can be extracted, and the file size limits for network, endpoint, and discovery functions. See: ● Supported File Formats ● File Size Limits © 2021 Forcepoint LLC Supported File Formats Supported File Formats and Size Limits | Forcepoint DLP | v8.8.1 The following tables lists the file formats supported by Forcepoint DLP. File formats are in alphabetical order by format group. ● Archive For mats, page 3 ● Backup Formats, page 7 ● Business Intelligence (BI) and Analysis Formats, page 8 ● Computer-Aided Design Formats, page 9 ● Cryptography Formats, page 12 ● Database Formats, page 14 ● Desktop publishing formats, page 16 ● eBook/Audio book formats, page 17 ● Executable formats, page 18 ● Font formats, page 20 ● Graphics formats - general, page 21 ● Graphics formats - vector graphics, page 26 ● Library formats, page 29 ● Log formats, page 30 ● Mail formats, page 31 ● Multimedia formats, page 32 ● Object formats, page 37 ● Presentation formats, page 38 ● Project management formats, page 40 ● Spreadsheet formats, page 41 ● Text and markup formats, page 43 ● Word processing formats, page 45 ● Miscellaneous formats, page 53 Supported file formats are added and updated frequently. Key to support tables Symbol Description Y The format is supported N The format is not supported P Partial metadata -

IDOL Keyview Filter SDK 12.8 C Programming Guide

IDOL KeyView Software Version 12.8 Filter SDK C Programming Guide Document Release Date: February 2021 Software Release Date: February 2021 Filter SDK C Programming Guide Legal notices Copyright notice © Copyright 2016-2021 Micro Focus or one of its affiliates. The only warranties for products and services of Micro Focus and its affiliates and licensors (“Micro Focus”) are as may be set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. Micro Focus shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Documentation updates The title page of this document contains the following identifying information: l Software Version number, which indicates the software version. l Document Release Date, which changes each time the document is updated. l Software Release Date, which indicates the release date of this version of the software. To check for updated documentation, visit https://www.microfocus.com/support-and-services/documentation/. Support Visit the MySupport portal to access contact information and details about the products, services, and support that Micro Focus offers. This portal also provides customer self-solve capabilities. It gives you a fast and efficient way to access interactive technical support tools needed to manage your business. As a valued support customer, you can benefit by using the MySupport portal to: l Search for knowledge documents of interest l Access product documentation l View software vulnerability alerts l Enter into discussions with other software customers l Download software patches l Manage software licenses, downloads, and support contracts l Submit and track service requests l Contact customer support l View information about all services that Support offers Many areas of the portal require you to sign in. -

Videoscape Quickstart Solution Installation and Configuration Guide

Videoscape Quickstart Configuration Guide Overview Introduction This document provides configuration guidelines for Cisco® Videoscape Quickstart. Release Details This section lists component version numbers and other details verified for this release. Release Type: Official Release Release Version: Quickstart Videoscape Media Suite (VMS) Version: VMS 4.1 Cisco Transcode Manager (CTM) Version: CTM 4.1 Content Delivery System-Internet Streaming (CDS-IS) Version: CDS-IS 2.5.11 Videoscape Quickstart Soft Client Version: Quickstart (1.0) Core Functions Videoscape Quickstart establishes core functions for the On-the-Go subscriber experience for TV Everywhere: 1 Content Preparation—Create multiple representations of the same VOD asset to support Adaptive Bit Rate Streaming received from multiple locations 2 Subscriber Authentication—Authenticate or deny access of a user to the on-line video portal 3 Entitlement—Enforce entitlement policies defined by the operator 4 Content Protection—Deliver encrypted version of VOD assets being offered through the on-line portal 5 Content Distribution—Stream or download a VOD asset to a portable device [ Document Version This is the first formal release of this document. OL-26112-01 1 Terms and Acronyms Terms and Acronyms The following table lists terms and acronyms used throughout this document. Term or Acronym Description ABR Adaptive Bit Rate Armada Legacy name of the application suite, formerly developed by Inlet, Inc., on which the CTM 4.1 suite is built. CDN Content Delivery Network CDS-IS Content Delivery System for Internet Streaming CDSM Content Delivery System Manager CTM Cisco Transcode Manager DRM Digital Rights Management OpenCASE Legacy name of the application suite, formerly developed by Extend Media, Inc., on which the Videoscape Quickstart Soft Client is built. -

Firmware Analysis of Linksys E900 V. 1.0.09.002

Firmware Analysis of Linksys E900 v. 1.0.09.002 HID Linksys E900 v. 1.0.09.002 Device Name E900 Vendor Linksys Device Class Routers Version 1.0.09.002 Release Date 1970-01-01 Size 7.39 MiB (7,746,560 Byte) Unpacker (v. 0.7) Plugin generic carver Extracted 2 Output: DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION ——————————————————————————– 0 0x0 BIN-Header, board ID: E900, hardware version: 4702, firmware v ersion: 1.0.0, build date: 2018-08-08 32 0x20 TRX firmware header, little endian, image size: 7745536 bytes, CRC32: 0x756770AD, flags: 0x0, version: 1, header size: 28 bytes, loader offset: 0x1C, linux kernel offset: 0x14FDFC, rootfs offset: 0x0 60 0x3C gzip compressed data, maximum compression, has original file n ame: ”piggy”, from Unix, last modified: 2018-08-08 05:28:28 1375772 0x14FE1C Squashfs filesystem, little endian, non-standard signature, ve rsion 3.0, size: 6365444 bytes, 1718 inodes, blocksize: 65536 bytes, created: 2018-08-08 05:33:15 Entropy 0.89 1 File Type (v. 1.0) File Type data MIME application/octet-stream Containing Files application/CDFV2 (2) application/gzip (1) application/octet-stream (3) application/x-executable (67) application/x-object (27) application/x-sharedlib (116) filesystem/squashfs (1) image/gif (42) image/jpeg (8) image/png (17) image/x-icon (1) inode/symlink (7) text/plain (990) 2 Binwalk (v. 0.5.2) Signature Analysis: DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION ——————————————————————————– 0 0x0 BIN-Header, board ID: E900, hardware version: 4702, firmware version: 1.0.0, build date: 2018-08-08 32 0x20 TRX firmware header, little endian, -

ASHS Is Inviting/Encouraging Poster Presenters to Up- Posters: Load a PDF of Their Poster

vt- •• ��t E�. Gallo Winery � BalL American Funding Generations of Floral Progress Through Research Image Analysis for Plant Science Endowment and Scholarships 1 of 262 General Information Conference Facilities: Speaker Ready Room: All Conference activities will take place at the Tropicana Oral, Workshop, Special Sessions, and Keynote speakers Las Vegas. are requested to check in at the Speaker Ready Room located in Churchill. Please note, even if you have Registration hours: uploaded in advance, you are still asked to check in at the Speaker Ready room at least 24 hours in advance of Sunday, July 21. .3:00 PM – 6:00 PM your presentation to confirm that your media and Pow- erPoint presentations were successfully uploaded and Monday, July 22 .............7:30 AM – 6:00 PM running properly. Updates and modifications can only Tuesday, July 23. 7:30 AM – 6:00 PM be made up to 24 hours in advance of your presentation. Wednesday, July 24. .7:30 AM – 5:00 PM Thursday, July 25 ............7:30 AM – 2:00 PM Poster Presenters and E-Posters: ASHS is inviting/encouraging poster presenters to up- Posters: load a PDF of their poster. You may also upload mp4 video or audio files to go along with the poster. Posters are located in Cohiba 5-12. As part of enhancing the ASHS online conference proceedings, you have the option to make your poster Poster Set Up: into an interactive electronic version (E-Poster). If you would like to explore this option, a link will appear once Monday, July 22 .............2:00 PM – 5:00 PM you have uploaded your PDF file with instructions on how to create your E-Poster. -

REVERSE ENGINEERING BROWSER COMPONENTS DISSECTING and HACKING SILVERLIGHT, HTML 5 and FLEX Shreeraj Shah

REVERSE ENGINEERING BROWSER COMPONENTS DISSECTING AND HACKING SILVERLIGHT, HTML 5 AND FLEX Shreeraj Shah http://www.blueinfy.com http://shreeraj.blogspot.com [email protected] WHO AM I? http://www.blueinfy.com » Founder & Director • Blueinfy & SecurityExposure » Past experience • Net Square (Founder), Foundstone (R&D/Consulting), Chase(Middleware), IBM (Domino Dev) » Interest • Application Security, Web 2.0 and RIA, SOA etc. » Published research • Articles / Papers – Securityfocus, O’erilly, DevX, InformIT etc. • Tools – wsScanner, scanweb2.0, AppMap, AppCodeScan, AppPrint etc. • Advisories - .Net, Java servers etc. • Presented at Blackhat, RSA, InfoSecWorld, OSCON, OWASP, HITB, Syscan, DeepSec etc. » Books (Author) • Web 2.0 Security – Defending Ajax, RIA and SOA • Hacking Web Services • Web Hacking 2 AGENDA » Bird eye view of Application security landscape » Reverse engineering – Source, Object and runtime » Analyzing Ajax, HTML5 and DOM based applications » Silverlight application review and assessments » Flash/Flex driven application assessments » Mobile – Browser driven apps » Defending applications » Conclusion » As we go • Demos • Tools – DOMScan, DOMTracer, XAPScan, AppCodeTrace, ScanDroid etc. • Tricks – Scans, FlashJacking, Eval the eval etc…. BIRD EYE VIEW CASE STUDIES » Applications reviewed – Banking, Trading, Portals, Social Networking, Manufacturing etc. (almost 10-15 apps per week) • DOM based XSS, Hidden business logic, Information leakage, RIA based hacks and attacks, BSQL over streams etc… (Getting missed) » Problem