Migration Patterns of Serbian and Bosnia and Herzegovina Migrants in Austria: Causes and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

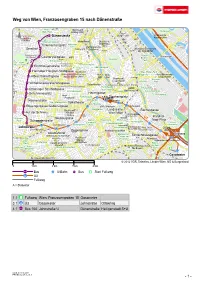

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897

THE GERMAN NATIONAL ATTACK ON THE CZECH MINORITY IN VIENNA, 1897-1914, AS REFLECTED IN THE SATIRICAL JOURNAL Kikeriki, AND ITS ROLE AS A CENTRIFUGAL FORCE IN THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. Jeffery W. Beglaw B.A. Simon Fraser University 1996 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History O Jeffery Beglaw Simon Fraser University March 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Jeffery Beglaw DEGREE: Master of Arts, History TITLE: 'The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897-1914, as Reflected in the Satirical Journal Kikeriki, and its Role as a Centrifugal Force in the Dissolution of Austria-Hungary.' EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Martin Kitchen Senior Supervisor Nadine Roth Supervisor Jerry Zaslove External Examiner Date Approved: . 11 Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author's written permission. -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

Migration Patterns of Serbian and Bosnia and Herzegovina Migrants in Austria: Causes and Consequences

August 2013 Research Reports | 389 | Isilda Mara, Hermine Vidovic and Michael Landesmann Migration Patterns of Serbian and Bosnia and Herze- govina Migrants in Austria: Causes and Consequences Isilda Mara and Hermine Vidovic are research economists at the Vienna Institute for Interna- Isilda Mara, Hermine Vidovic tional Economic Studies (wiiw). Michael Landes- and Michael Landesmann mann is wiiw Research Director and Professor of Economics at Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Migration Patterns of Austria. The survey analysed in this study was con- ducted by the Austrian Gallup Institute. Serbian and Bosnia and Herzegovina Migrants in Research for this paper was financed by the Jubilee Fund of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Project Austria: Causes and Con- No. 14117). sequences Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................................... i Executive summary ................................................................................................................. ii 1. Introduction and motivation of research .......................................................................... 1 2. Background information ................................................................................................... 3 3. Demographic and economic characteristics of Serbian migrants versus other groups of migrants in Austria .................................................................................. 6 4. New insights from the recent survey -

Grätzl-Rallye 17. Bezirk

Grätzl-Rallye 17. Bezirk LÖSUNGSHEFT Liebe Pädagogin! Lieber Pädagoge! Wir freuen uns, dass Sie gemeinsam mit Ihren Kindern an der Grätzl-Rallye durch Hernals teilnehmen und sich zu Fuß auf diese Entdeckungsreise begeben. Wir wünschen Ihnen dabei viel Spaß und Erfolg! Um einen gelungenen Ablauf der Grätzl-Rallye zu garantieren, möchten wir Ihnen hier einige Infos und Tipps mit auf den Weg geben: Beachten Sie bitte, dass es sich bei der Grätzl-Rallye um keine geführte Tour handelt, und dass Sie entsprechend viele Begleitpersonen einplanen (mind. eine Person pro Gruppe). Für die Kinder gibt es ein eigenes Rätselheft. In diesem finden sie Hinweise auf den richtigen Weg durch den Bezirk und kleine Rätsel, um das Lösungswort zu knacken. Verschiedene Symbole unterstützen die Kinder dabei (s. nächste Seite). Im vorliegenden Lösungsheft finden Sie zusätzlich zu den Hinweisen für die Kinder auch die richtigen Antworten sowie Hintergrundinformationen. So können Sie die Kinder bei Bedarf unterstützen. Die vollständige Route finden Sie auf untenstehender Karte. Wir wünschen Ihnen viel Spaß beim Stadt-Entdecken! Die weiß hinterlegten Felder beinhalten Weg- beschreibungen, die auch im Kinderheft angegeben sind. In den grün hinterlegten Feldern gibt es Hinter- grundinfos zum Erzählen. Wegbeschreibung Die Kinder suchen einen Hinweis in der Ferne, etwa an einer Start: Straßenbahnhaltestelle Hausfassade oder auf der gegenüberliegenden Straßenseite. „Palffygasse“ Die Kinder suchen einen Hinweis in ihrer Nähe, etwa auf einem Anfahrt: Straßenbahn 43 Schild oder an einer Hauswand. Ziel: Hier müssen die Kinder eine Aufgabe lösen oder eine kleine Spielplatz Lorenz-Bayer-Park 1 Abfahrt: Straßenbahn 2, 9, 44 Übung im Stadtraum machen. (Station „Johann-Nepomuk-Berger-Platz“) Die eingekreisten Buchstaben ergeben in der richtigen Reihen- Dauer der Grätzl-Rallye ca. -

First Vienna Residential Market Report | 2021 02

FIRST VIENNA RESIDENTIAL MARKET REPORT EDITION 2021 Illus fehlen hier noch EDITORIAL issues such as: What role does digitalisation play in the residential space? DEAR READER How can we best combine sustainability and affordability in residential de- velopment projects? How will future residential project planning respond We are pleased to present the First Vienna Residential Market Report, the to the increased trend of working from home in the light of the pandemic? ninth edition of our joint publication. We will be going into this last question on page 14. THIS HAS BEEN A TURBULENT YEAR with the pandemic leav- ing its mark on every aspect of the economy, resulting in long-term ef- fects for many. The real estate industry has not remained unscathed by the crisis, although the residential market is showing significantly more “The past year has brought even more focus on stability: The demand for residential accommodation remained high in the home, raising important questions concern- 2020 – probably due to the fact that residential property is a safe form of investment in general. ing the housing market.” THE HIGH DEMAND also resulted from constantly increasing numbers of one-person households and the continued rise in Vienna’s population, which is due to reach the two million mark in 2028. In contrast, property IN THE FIRST VIENNA RESIDENTIAL MARKET REPORT, we developers in 2021 will still have challenges to face as land available for will be sharing our experience and expertise for a more in-depth and com- development has become scarce in the capital and construction costs are prehensive insight into the market. -

EHL First Vienna Residential Market Report

FIRST VIENNA RESIDENTIAL MARKET REPORT EDITION 2019 EDITORIAL DEAR READER We are pleased to present the First Vienna Residential Market Report for lations. If this trend continues, it will have a significant impact on housing the seventh time. costs, and especially the possibility of financing entire projects. Vienna was not only selected as the city with the highest quality of life for We at the BUWOG Group and EHL Immobilien are familiar with the chal- the ninth year in a row as part of the Mercer Study last year; Austria’s capital lenges that the Vienna housing market is facing. We are dealing intensively outranked Melbourne, Australia, after seven years at the top according to with housing needs and requirements that need to be met now and in the the British Economist. future, for people of every generation. Changing values, digitalisation and sustainability are not just buzzwords for us. These concepts play a major Even so, the huge popularity of Vienna has also given rise to a number of role in the planning and construction of housing projects that will also need challenges for the city: the population has been rising steadily, and is pro- to reflect the demands of society in years to come. We are doing our best jected to reach around two million inhabitants by 2026. This development to ensure that our customers and the residents of Vienna enjoy adequate has led to years of demand outstripping supply on the Vienna housing state-of-the-art housing with correspondingly high quality of living both today market as well as land scarcity that housing developers in particular have and in the future. -

Direct Lines to Vienna City Centre

Vienna Nußdorf Vienna Floridsdorf U6 Readymix Heiligen- DIRECT LINES TO VAL 3 stadt U4 Pony- Kagran/ teiche VIENNA CITY CENTRE Donauzentrum Badeteich Oberdöbling Handelskai Hirschstetten Railjet: in just 15 minutes from Vienna Airport AUSTRIA CENTER VIENNA: MAIN CONFERENCE to Wien Hauptbahnhof (Central Station) LOCATION OF THE EU PRESIDENCY Krotten- Please note that the name of the public transport station is Every 30 minutes, the ÖBB Railjets Vienna International Centre (VIC). connect the two stations Vienna bachstr. Spittelau Hirsch- Airport and Wien Hauptbahnhof. stetten ÖBB Railjet trains are a rapid (about Traisengasse 15 minutes travel) and comfortable Gersthof Kaisermühlen VIC service between Vienna Airport and Erzherzog- Wien Hauptbahnhof (Vienna´s main train station) where you can change Karl-Str. to connecting lines (underground, Franz-Josef- © ÖBB/Harald Eisenberger long-distance and local services). Bahnhof Seestadt Railjet trains also offer attractive direct connections from VIE to other Austrian Hernals U2 cities like St. Pölten, Linz, Salzburg, Innsbruck and Graz. Schwedenplatz Praterstern Stadlau Vienna VAL 2 VAL 3 7 Suburban trains: a perfect way to connect Unteres Mühlwasser to Vienna‘s underground metro lines Vienna City Krieau Ottakring Centre With the ÖBB suburban train S7 U3 Rathaus Unteres you travel fast and safely from Vienna Mühlwasser Donaumarina Vienna Airport to Vienna. Stephans- Mitte The services connect the airport up to platz four times an hour with the Viennese VAL 2 underground network. This suburban Volkstheater Mühlwasser GROSS-ENZERSDORF fer Arm rail network offers connections to U2 Groß Enzendor a wide range of other underground Vienna Mühlwasser Vienna Hütteldorf Groß Enzendor stations in Vienna (e.g. -

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria Subsidizes Scientific And

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria subsidizes scientific and pedagogical projects which foster tolerance and mutual understanding on the basis of a close examination of the sufferings caused by the Nazi regime on the territory of present-day Austria. Keeping alive the memory of the victims as a reminder for future generations is one of our main targets, as well as human rights education and the strengthening of democratic values. Beyond, you will find a list containing the English titles or brief summaries of all projects approved by the Future Fund since its establishment in 2006. For further information in German about the content, duration and leading institutions or persons of each project, please refer to the database (menu: “Projektdatenbank”) on our homepage http://www.zukunftsfonds-austria.at If you have further questions, please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] Project-Code P06-0001 brief summary Soviet Forced Labour Workers and their Lives after Liberation Project-Code P06-0002 brief summary Life histories of forced labour workers under the Nazi regime Project-Code P06-0003 brief summary Unbroken Will - USA - Tour 2006 (book presentations and oral history debates with Holocaust survivor Leopold Engleitner) Project-Code P06-0004 brief summary Heinrich Steinitz - Lawyer, Poet and Resistance Activist Project-Code P06-0006 brief summary Robert Quintilla: A Gaul in Danubia. Memoirs of a former French forced labourer Project-Code P06-0007 brief summary Symposium of the Jewish Museum Vilnius on their educational campaign against anti-Semitism and Austria's contribution to those efforts Project-Code P06-0008 brief summary Effective Mechanisms of Totalitarian Developments. -

Laxenburg Karlsplatz

21. Floridsdorf 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 19. 13 14 15 16 25 42 22. 40 Döbling 38 Donaustadt 20. 17. Hernals 18. Brigittenau Währing 9. Alsergrund 23 30 32 24 16. 27 227 8. 39 18 14. Ottakring Josefstadt 2. 28 33 34 30 Schottenring 31 Leopoldstadt Penzing 7. 35 371.36 41 Neubau Innere Stadt Neutorgasse 19 17 15. 29 3. Kolingasse 21 20 Landstraße 32 Rudolfsheim- 6. Votivkirche Mariahilf 4. Schottenring International Fünfhaus Wieden 5. Schottentor 24 Margarethen 227 Taborstraße Universität Wien 39 13. 11. Freyung organisations 18 Hietzing 12. Simmering 34 Schwedenplatz Meidling Burgtheater 37 1. Innere Stadt Wiener St. Peter Minoritenkirche Universitätsring Kirche Bäckerstraße Herrengasse Stubenring and institutions Wollzeile St. Michael Volksgarten Kirche 10. Stubentor 23. Hofburg Wien Stephansplatz 33 Singerstraße Favoriten Schatzkammer Wien 31 based in Vienna Weihburggasse Liesing Heldenplatz Österreichische Himmelpfortgasse Naturhistorisches Nationalbibliothek Museum Burgring Volkstheater Parkring Albertina and surroundings Kunsthistorisches Museum Haus der Musik Stadtpark 28 Opernring 36 Stadtpark Museumsquartier Kärntner Ring 22 Schubertring 26 Laxenburg Karlsplatz ORGANISATIONS AND ENTITIES OTHER INTERNATIONAL OF THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANISATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS 01. UNOV 07. UNOIOS 12. UNPA 17. COE 24. ICMPD 31. OFID United Nations Office at Vienna (United Nations) Office of Internal United Nations Postal Administration Council of Europe Liaison Office International Centre for Migration OPEC Fund for International Development -

Die Dynamik Ethnischer Wohnviertel in Wien

JOSEF KOHLBACHER und URSULA REEGER DIE DYNAMIK ETHNISCHER WOHNVIERTEL IN WIEN Eine sozialräumliche Longitudinalanalyse 1981 und 2005 VERLAG DER ÖSTERREICHISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN WIEN 2006 1 Zusammenfassung Im Rahmen unseres Forschungsvorhabens wurde die Verteilung der Migranten- bevölkerung aus dem ehemaligen Jugoslawien im Wiener Stadtraum im Vergleich zwischen den Jahren 1981 und 2005 analysiert. Von der Erhebung des Jahres 1981 unter E. Lichtenberger waren 750 Hauserhebungsbögen im Archiv des Instituts für Stadt- und Regionalforschung vorhanden. Aus Gründen der Vergleichbarkeit erwies es sich 2005 als möglich, 696 Häuser in die Analysen einzubeziehen. Das Sample umfasste damals Wohnhäuser, in denen 1981 ein oder mehrere jugoslawische Gastarbeiterhaushalte ansässig waren, verteilt über sämtliche Wiener Gemeindebezirke. Die Stichprobenziehung der Ersterhebung erfolgte auf der Grundlage von Meldedaten der Fremdenpolizei. Der Wohndistribution der exjugoslawischen Gastarbeiterbevölkerung im Wiener Stadtraum entsprechend sind die Arbeiterbezirke deutlich überrepräsentiert gegenüber den Cottagevierteln. Ottakring nimmt mit einem Anteil von 10,6% (74 Häuser) den Spitzenplatz in unserer StichprobeDie Ergebnisse ein. sind ambivalent, obwohl – und dies ist die gute Nachricht – groß- räumige Zuwandererghettos in Wien nach wie vor nicht existieren. Die schlechte Botschaft ist, dass es den Gastarbeiterbezirken von 1981 offensichtlich nicht gelun- gen ist, im Verlauf der vergangenen zweieinhalb Jahrzehnte eine grundlegende Imageverbesserung -

Human Development Indices and Indicators

Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018 Statistical Update The cover reflects human development progress over 1990–2017 in terms of Human Development Index (HDI) values and the number of people in the four human development categories. In the figure each slice’s innermost band represents the population in that human development category, and the height of the slice reflects its HDI value. The cover reflects that even though the global population increased from 5 billion to 7.5 billion between 1990 and 2017, the number of people in low human development fell from 3 billion to 926 million—or from 60 percent of the global population to 12 percent—and that the number of people in high and very high human development more than tripled, from 1.2 billion to 3.8 billion—or from 24 percent of the global population to 51 percent. ent elopm Ve dev ry h an igh m hu hu Hum m w an D an o ev d L elo e pm ve 0.8 en lo 94 t I p nd m 0.504 e e x n v a t lu e 6 m 1.439 b 92 n pe o p l e M 2017 2 e . 7 d 3 i 3 HDI n u b m b n 9 7 h 0.645 .3 u 2 m a n d e t v n e e lo m p p m lo e 0.757 e n v t e d an um h gh Hi Copyright @ 2018 By the United Nations Development Programme 1 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017 USA All rights reserved.