Transforming the Trent Valley: Cultural Heritage Audit Summary Report SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Bonehill Mews Lichfield Street Fazeley Tamworth B78 3Qn

G.25533 TO LET A SELF CONTAINED OFFICE BUILDING WITH ADJACENT PARKING 4 BONEHILL MEWS LICHFIELD STREET FAZELEY TAMWORTH B78 3QN 2,796 SQ.FT. (260 SQ.M.) NET WITH DOUBLE GLAZING, HEATING AND CATEGORY II LIGHTING AIR CONDITIONING TO PART PRIVATE KITCHEN AND WC/WASH FACILITIES WELL SITUATED WITHIN APPROXIMATELY 3MILES OF M42 J10 AND 5 MILES OF M6 TOLL JT3 LOCATION Bonehill Mews is a modern development of four self contained buildings and is well situated off Lichfield Street, Fazeley within approximately 1.75 miles of the A5 trunk road, 3 miles of the M42 motorway Junction 10 and 5 miles from the M6 Toll Junction T3. DESCRIPTION A self contained two storey building providing modern open plan office accommodation completed with fitted carpets, electric heating, double glazing to external windows, category II lighting and air conditioning to part of the first floor as follows: GROUND FLOOR Entrance Lobby With male, female and disabled wc/wash facilities off. Open Plan Office 1,622 sq.ft. net Area (150.68 sq.m.) FIRST FLOOR Kitchen 76 sq.ft. With vinyl sheet floor covering, stainless steel sink unit (7.12 sq.m.) and fitted work top. Open Plan Office 1,098 sq.ft. net Area (102.02 sq.m.) Total Net Internal 2,796 sq.ft. Floor Area (260 sq.m.) TO THE EXTERIOR The property has the benefit of eleven private car parking spaces within the adjacent forecourt area. TENURE The property is available “TO LET” by way of a new full repairing and insuring Lease for a term of years by agreement. -

Fazeley Town Council

Fazeley Town Council Minutes of the Meeting of the Town Council held in the Main Hall, Fazeley Town Hall on Monday, 9th December 2019 at 7.30pm Councillors Present: B Hoult, N Claymore, J Dann, S Bree, M Hoult, J Atkins and A Farrell Also Present: PCSO Margaret Griffiths R Young, Clerk to the Council Apologies: D Dwyer, O Shepherd, J Sadler and B Gwilt Prior to the start of the meeting, PCSO Margaret Griffiths discussed Policing Issues with Councillors and the Town Mayor, B Hoult, distributed grants to local organisations. 109) Declarations of Interest No declarations were made. 110) Minutes It was proposed (A Farrell), seconded (S Bree) and agreed that the Minutes (93-103) of the Town Council Meeting held on the 11th November 2019 be approved as a true and correct record. Resolved: That the Minutes (93-103) of the Ordinary Meeting of the Town Council held on the 11th November 2019 be approved as a true and correct record. 111) Actions Brought Topic Description Updated Planned Councillor to Action Date Resolution Sponsor Council Date 2018 Neighbourhood Working group to produce Meeting with 2022 JS Plan N.P. Kershaws 2019 Additional Confirmed N.B. size of Ongoing Feb 2020 Noticeboard 105cm x 105cm to Sandhu Stores. 2019 Website O Shepherd to update. Ongoing 2020 OS/AF Minutes - 09.12.19 Page 1 Brought Topic Description Updated Planned Councillor to Action Date Resolution Sponsor Council Date 2019 Town Hall Completion of painting Ongoing – 2020 --- Painting Spring 2020. Front door needs attention. 2019 Land opposite Ongoing with SCC Legal Property 2020 JA/JS Evans Croft ownership problem. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

Surface Water Management Plan Phase 1

Southern Staffordshire Surface Water Management Plan Phase 1 Stafford Borough, Lichfield District, Tamworth Borough, South Staffordshire District and Cannock Chase District Councils July 2010 Final Report 9V5955 CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General Overview 1 1.2 Objectives of the SWMP 1 1.3 Scope of the SWMP 3 1.3.1 Phase 1 - Preparation 5 1.3.2 Phase 2 - Risk Assessment 5 2 ESTABLISHING A PARTNERSHIP 7 2.1 Identification of Partners 7 2.2 Roles and Responsibilities 9 2.3 Engagement Plan 10 2.4 Objectives 10 3 COLLATE AND MAP INFORMATION 11 3.1 Data Collection and Quality 11 3.1.1 Historic Flood Event Data 12 3.1.2 Future Flood Risk Data 15 3.2 Mapping and GIS 18 3.2.1 Surface Water Flooding 18 3.2.2 Flood Risk Assets 19 3.2.3 SUDS Map 19 3.2.4 Summary Sheets 20 4 STAFFORD BOROUGH 23 4.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 23 4.2 Surface Water Management 24 4.3 Recommendations 25 5 LICHFIELD DISTRICT 27 5.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 27 5.2 Surface Water Management 28 5.2.1 Canal Restoration 29 5.3 Recommendations 31 6 TAMWORTH BOROUGH 33 6.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 33 6.2 Surface Water Management 34 6.3 Recommendations 35 7 SOUTH STAFFORDSHIRE DISTRICT 37 7.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 37 7.2 Surface Water Management 38 7.2.1 Canal Restoration 39 7.3 Recommendations 41 Southern Staffordshire SWMP Phase 1 9V5955/R00003/303671/Soli Final Report -i- July 2010 8 CANNOCK CHASE DISTRICT 43 8.1 Surface Water Flood Risk 43 8.2 Surface Water Management 44 8.2.1 Canal Restoration 45 8.3 Recommendations 47 9 SELECTION OF AN APPROACH FOR FURTHER ANALYSIS -

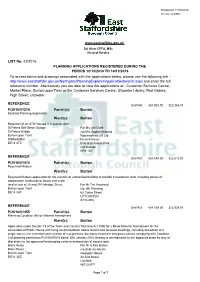

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications Below, Please Use the Following Link

Printed On 17/10/2016 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 42/2016 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 10/10/2016 TO 14/10/2016 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 424,802.00 : 322,266.00 P/2016/01214 Parish(s): Burton Detailed Planning Application Ward(s): Burton Retention of an ATM housed in a secure room St Peters Self Serve Garage For Ms Jan Clark St Peters Bridge c/o Mrs Sophie Wilbond Burton upon Trent Notemachine UK Ltd Staffordshire Russell House DE14 2TZ Elvicta Business Park Crickhowell NP8 1DF REFERENCE Grid Ref: 424,439.00 : 322,613.00 P/2016/01414 Parish(s): Burton Reserved Matters Ward(s): Burton Reserved Matters application for the erection of a detached building to provide 8 residential units including details of appearance, landscaping, layout and scale land to rear of 26 and 29 Uxbridge Street For Mr Tim Haywood Burton upon Trent c/o JMI Planning DE14 3JR 62 Carter Street UTTOXETER ST14 8EU REFERENCE Grid Ref: 424,169.00 : 322,926.00 P/2016/01455 Parish(s): Burton Planning Condition (Minor Material Amendment Ward(s): Burton Application under Section 73 of -

Lichfield District Local Plan Review Preferred Options

For Official Use Respondent No: Representation Number: Received: Lichfield District Local Plan Review Preferred Options Please return to Lichfield District Council by 5pm on 24th January 2020, by: Email: [email protected] Post: Spatial Policy and Delivery, Lichfield District Council, District Council House, Frog Lane, Lichfield, WS13 6YZ. This form can also be completed on line using our consultation portal: http://lichfielddc- consult.limehouse.co.uk/portal PLEASE NOTE: This form has two parts: Part A: Personal details. Part B: Your representation(s). Part A: Personal details 1.Personal details1 2 2. Agent’s details (if applicable) Title Mrs First name Anna Last Name Miller Job Title (where relevant) Assistant Director – Growth and Regeneration Organisation (where relevant) Tamworth Borough Council House No./Street Marmion House, Lichfield Street Town Tamworth Post Code B79 7BZ Telephone Number 01827 709709 Email address (where relevant) anna- [email protected] 1 If an agent is being used only the title, name and organisation boxes are necessary but please don’t forget to complete all the Agent’s details. 2 Please note that copies of all comments received will be made available for the public to view, including your address and therefore cannot be treated as confidential. Lichfield District Council will process your personal data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. Our Privacy Notice is at the end of this form. Part B: Your representation Where in the document does your comment relate: Part of document Various – please see below General comments: The Council notes that the proposed new local plan is intended to replace the current local plan strategy (2015) and local plan allocations document (2019). -

Part 1.7 Trent Valley Washlands

Part One: Landscape Character Descriptions 7. Trent Valley Washlands Landscape Character Types • Lowland Village Farmlands ..... 7.4 • Riverside Meadows ................... 7.13 • Wet Pasture Meadows ............ 7.9 Trent Valley Washlands Character Area 69 Part 1 - 7.1 Trent Valley Washlands CHARACTER AREA 69 An agricultural landscape set within broad, open river valleys with many urban features. Landscape Character Types • Lowland Village Farmlands • Wet Pasture Meadows • Riverside Meadows "We therefore continue our course along the arched causeway glancing on either side at the fertile meadows which receive old Trent's annual bounty, in the shape of fattening floods, and which amply return the favour by supporting herds of splendid cattle upon his water-worn banks..." p248 Hicklin; Wallis ‘Bemrose’s Guide to Derbyshire' Introduction and tightly trimmed and hedgerow Physical Influences trees are few. Woodlands are few The Trent Valley Washlands throughout the area although The area is defined by an constitute a distinct, broad, linear occasionally the full growth of underlying geology of Mercia band which follows the middle riparian trees and shrubs give the Mudstones overlain with a variety reaches of the slow flowing River impression of woodland cover. of fluvioglacial, periglacial and river Trent, forming a crescent from deposits of mostly sand and gravel, Burton on Trent in the west to Long Large power stations once to form terraces flanking the rivers. Eaton in the east. It also includes dominated the scene with their the lower reaches of the rivers Dove massive cooling towers. Most of The gravel terraces of the Lowland and Derwent. these have become Village Farmlands form coarse, decommissioned and will soon be sandy loam, whilst the Riverside To the north the valley rises up to demolished. -

Staffordshire. [Kelly:S

6i2 FAH. STAFFORDSHIRE. [KELLY:S .FAH:Mlm3-continued. 1 Bailey C. H. Dale ho. Cheddleton, Leek BarkerE.Heighley,Knowle End.Nwcstl .Askew Mrs. Charles, Barton-under- 1 Bailey Mrs. Elizabeth, Rolleswn, Brtn B;uker Mrs. E. 1\I.Hanchurch, Nwcstl Needwood, Burton Bailey Fras. Alan, Beech, Newcastle Barker Hy. 'Rough close, Blnrton,Stke ~skey \Vm. Holly wood, Sandon, Stone Bailey Geo. Middleton Green, Stoke Barker Henry K. Rough close, Stone Aspley Rchd. Muckley corner, Lichfield Bailey (}eorge, Standeford, \V'hampton Barker .Tames, Knight's fields, Wood- Astbury John Charles, Morfe hall, Bailey Henry, Alrewas, Burton lands, Uttoxeter Enville, Stourbridge Bailey J. Chatsworth, Norton, Leek Barker .Tesse, Knowle End, Newcastle Astbury Mrs. Martha, Oulton house, Bailey .Job, Moor top, Norton, Leek Barker .Tohn, Fanld, Bnrton Milwich, Stone Bailey John, Foie, Stoke Barker Samuel, Audley, Newcastle Astin Edwin, Ashley, Market Drayton Bailey John, Greenway bank, Norton- Barker SHml. Blare, Market Drayton Astle E. Holly bk. Armitage, Rugeley in-the-Moor~. Stoke Barker Thomas, Calton, A:shbourne Astle T. Holly bk. Annitage, Rugeley Bailey .J. Booths, Ipstones, Stoke BarkPr William, Brettell lane, Amble- Astley Edward, Mill bank, Longdon, Bailey J. Parkhouse, Leek .Frith, Stoke cote, Stourbridge Rugeley Bailey J. Wood end. Wetley Rocks,Stke Barker W. Town end, Wetton, .Ashbrn .Aston G. Wheaton .Aston, Stafford Bailey Luke, Great Ched, Stoke Barks George, Cotton lane, Cotton, Aston John, Pattingham, W'hampton Bailey .Xathan, Ditchway, Rushton Cheadle, Stoke Aston \Vm. Seisdon, Wolverhampton Spencer, 1\iacclesfield Barks .J. Broomyshaw,Cauldon,.Ashbrn .At b.crton J uhn, Golden Hill, Stoke Bailey N a than, Long Edge la.n~. -

Infrastructure Delivery Plan

East Staffordshire Borough Council Infrastructure Audit and Delivery Plan Infrastructure Delivery Plan Issue Final | 17 October 2013 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 231577-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd The Arup Campus Blythe Gate Blythe Valley Park Solihull B90 8AE United Kingdom www.arup.com Document Verification Job title Infrastructure Audit and Delivery Plan Job number 231577-00 Document title Infrastructure Delivery Plan File reference Document ref Issue Revision Date Filename East Staffordshire Infrastructure Delivery Plan.docx Draft 1 16 Sep Description First draft 2013 Prepared by Checked by Approved by Rebecca Ford, Anna Shafee, Andy Name Rebecca Ford Mark Smith Hardy, Hannah Smith Signature Final draft 10 Oct Filename East Staffordshire Infrastructure Delivery Plan.docx 2013 Description Final draft Prepared by Checked by Approved by Rebecca Ford, Anna Shafee, Andy Name Rebecca Ford Mark Smith Hardy, Hannah Smith Signature Final issue 1 7 Oct Filename East Staffordshire Infrastructure Delivery Plan Final Issue.docx 2013 Description Final Issue Prepared by Checked by Approved by Rebecca Ford, Anna Shafee, Andy Name Anna Shafee Rebecca Ford Hardy, Hannah Smith Signature Issue Document Verification with Document Issue | Final | 17 October 2013 East Staffordshire Borough Council Infrastructure Audit and Delivery Plan Infrastructure Delivery -

Practice Leaflet for Patients

ABOUT LAUREL HOUSE SURGERY PRACTICE MANAGER Laurel House was founded by Dr McFee around 1910 CRAIG DORRINGTON followed by Dr McColl. Dr Goodliffe and Dr Weston Smith PRACTICE FINANCE MANAGER LAUREL HOUSE SURGERY then ran the surgery which was where Dr Weston Smith DAVID HICKEN BA (Hons), FCIPD, MIHM lived for many years. Since then the surgery has progressed PRACTICE NURSES and today offers a wide variety of facilities, including RACHEL YOUNG RGN computer aided records which help our busy practice ANGELA DAWN RGN operate efficiently and expert staff who aim to deliver high HEALTH CARE ASSISTANTS PRACTICE quality patient care. CHARLOTTE BRIGHT & EMMA LARGE We have ten Doctors who employ a wide range of specially PRACTICE PHARMACIST LEAFLET trained staff. All members of staff are bound by the same Karen Crosby rules of confidentiality as your clinicians. They are likely to PRACTICE MIDWIFE ask you questions to help further your treatment and book Information for KATIE KINSELLA– LAUREL HOUSE you an appointment with the most appropriate clinician. Practice Nurses offer various clinics, deal with immunisations PRACTICE PHLEBOTOMIST Patients Appointments ONLY and will answer your queries on most health matters. The practice offers the following clinics: Antenatal, Diabetic, Coronary Heart Disease, Asthma, Minor The Freedom of Information Act gives you the right to request information held by a public sector organisation. Surgery and medicals CLINICAL COMMISSIONING GROUP (CCG) Unless there’s a good reason, the organisation must provide the We are proud of the service we offer to our patients. If you To obtain details of all primary medical services available, information within 30 working days. -

Peel's Wharf, Lichfield Street, Fazeley, Tamworth, B78 3QZ Tel: 0303 0404040

- From the North & Lichfield (A38) ´ Peel's Wharf, Lichfield Street, Fazeley, Tamworth, B78 3QZ Tel: 0303 0404040 A5 A495 Derby Tamworth A 5 A1 we A38 M6 st & t A42 oll Shrewsbury M54 Leicester A458 A5 A49 A6 A43 M1 Birmingham M6 M42 A45 M5 A45 Northampton A44 Worcester A46 See Inset Wilnecote By Train (Staffs) - The Canal & River Trust Fazeley office can be accessed by Wilnecote (1.1miles) and Tamworth (2.1miles) train stations. The office is a 20-25 J10 A 5 S minute walk from Wilnecote train station. ou & th M1 Exit Wilnecote Station, turn left onto the B5404 (Watling Street). Keep walking straight. Peel’s Wharf is on the right past the humpback bridge over Inset to ld the canal (Route will take approximately 20-25mins). th e u fi o ld S o 3 C 5 n Due to the distance and complicated route, it is not recommended to walk 4 o A tt u from Tamworth Station. Taxis are available from Tamworth Station. S By Car - From the south or north-east: take the M42 to junction 10 with the A5. Take the A5, then turn left onto the A453 (signposted Sutton Coldfield). Turn left at the traffic lights with the B5404 (Watling Street). The office is just over 1mile along the road on the left hand side. T3 - From the west: take the M6 onto the M42 and follow instructions as above. Alternatively, take the M6 toll and exit left onto the A5. Take the 3rd exit onto the A5 signposted ‘Tamworth’ and follow until the exit for the A453 (signposted Sutton Coldfield). -

Research Log

RESEARCH LOG ANCESTOR: Lorenzo/ Lorenza Brown (wife Mary Ann Macklin) BIRTH DATE: 4 Feb 1855, Dudley Worcestershire England SPOUSE: Mary Ann Macklin PARENTS: John Brown and Sarah Thornton OBJECTIVES: Find information about Lorenzo Brown to LOCATION: Born Dudley, Worcestershire prove relationships to his parents, his wife and to their Lived in Hammerwich and Fazeley, Staffordshire children Date Call Number Description Of Source Comments Document Number 12 January Online The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Nothing Nil 2006 Saints "Ancestral File," database. FamilySearch. (www.familysearch.org 12 January Online The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Extracted marriage record for Lorenzo and 2006 Saints "International Genealogical Index," Mary Ann: 17 May 1875 at Ogley Hay; database. FamilySearch. Source: 1040781; Batch M167301 (www.familysearch.org) 29 January FH Library at Ogley Hay Parish, (Staffordshire, Marriage record of Lorenzo Brown and DOC 2006 Salt Lake City England), Parish Registers, 1849-1900, Mary Ann Macklin L-1 British Film # Staffordshire County Record Office. 1040781 (4-5) Marriages 1854-1876 12 January Online "1881 England Census," Database. The Lorenzo and Mary Brown at Brook End in DOC 2006 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Fazeley with two daughters: Hannah and L-2 Saints. FamilySearch. Eliza. (www.familysearch.org) 12 January Online "1881 England Census," Ancestry.com; Image of 1881 census "Brook End" DOC 2006 Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com) Fazeley, Staffordshire [RG11/2770, ED 6, L-3 p. 19 household #80] 20 Apr Online Free BMD; The Trustees of FreeBMD Birth entry for Lorenzo Brown 2006 (Ben Laurie, Graham Hart, Camilla von March 1855 Quarter, Dudley Registration Massenbach and David Mayall); District; Vol 6c, p 147.