August 2010 PROTECTION of AUTHOR ' S C O P Y R I G H T This Copy Has Been Supplied by the Library of the University of Otago O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 1988

THE LONG BATTLE FOR EQUAL PAY-TRUMPS OR TRUCE? TENTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION OCTOBER 1988 Playwright Renee Talks for the first tii The Mervyn Thomi VIOTHERHOOi wo W om en’s Stories WAHIA PUBLI < Growing Future or M aori Artists t Writers LIBRARY AUCKLAND OLLEGE OF El REBEL OR REACTIONARY? t u r n % The Gluepot Hotel in Ponsonby will host two seasons of comedy cabaret Dare Swan during the Festival. Tickets $16 inc. Booking and GST. O C3 Tue 25th to Sat 29th October. 8pm nightly, Matinee 2pm Sat. The Auckland Comedy Festival will showcase a season by Sydney dance company Dare Swan at the Maidment Theatre in the last week of October. Dare Swan (pictured below) was founded in 1982 and comprises New Zealanders Chris Jannides and Kilda Northcott, founding members of Limbs Dance Cabaret — Week One. Company, Peta Rutter, formerly of Slick Stage, as Oct 26-29. Gluepot. well as Australian’s Kaye Freeman and Anastasi Siotasis. Red Mole join local Comedy- store star Chris Hegan, Sydney mime Ira Seidenstein, and the father of the Christchurch Fringe, River, for a three hour cabaret show, running Wednesday to Saturday in the first week of the Festival. Aucklanders will remember Red Mole from their work in the late seventies, and their appearance at the Sweetwaters Festival in 1980. The core of the group (pictured above), now based in Wellington after a decade of work in America and Europe, will return to Auckland for the Comedy Festival with newly created B O O K ^ a ^ S cabaret material. MmmoKmm Mmmmmm ■ m m H p e r iv n I 1 L f J U 1 T VJL i Presented by Expression Multi-media and the Aotea Centre in association with No Ordinary beer. -

Ddc Master Status

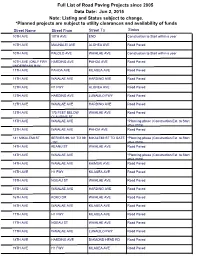

Full List of Road Paving Projects since 2005 Data Date: Jun 2, 2015 Note: Listing and Status subject to change. *Planned projects are subject to utility clearances and availability of funds Street Name Street From Street To Status 10TH AVE 10TH AVE END Construction to Start within a year 10TH AVE MAUNALEI AVE ALOHEA AVE Road Paved 10TH AVE PALOLO AVE WAIALAE AVE Construction to Start within a year 10TH AVE (ONLY FWY HARDING AVE PAHOA AVE Road Paved UNDERPASS R/W) 11TH AVE PAHOA AVE KILAUEA AVE Road Paved 11TH AVE WAIALAE AVE HARDING AVE Road Paved 12TH AVE H1 FWY ALOHEA AVE Road Paved 12TH AVE HARDING AVE LUNALILO FWY Road Paved 12TH AVE WAIALAE AVE HARDING AVE Road Paved 13TH AVE 175 FEET BELOW WAIALAE AVE Road Paved CLAUDINE ST 13TH AVE WAIALAE AVE *Planning phase (Construction Est. to Start after 2015) 13TH AVE WAIALAE AVE PAHOA AVE Road Paved 141 MIKALEMI ST SERVES 99-141 TO 99 MIKALEMI ST TO GATE *Planning phase (Construction Est. to Start -151 after 2015) 14TH AVE KEANU ST WAIALAE AVE Road Paved 14TH AVE WAIALAE AVE *Planning phase (Construction Est. to Start after 2015) 14TH AVE WAIALAE AVE KAIMUKI AVE Road Paved 15TH AVE H1 FWY KILAUEA AVE Road Paved 15TH AVE NOEAU ST WAIALAE AVE Road Paved 15TH AVE WAIALAE AVE HARDING AVE Road Paved 16TH AVE KOKO DR WAIALAE AVE Road Paved 16TH AVE WAIALAE AVE KILAUEA AVE Road Paved 17TH AVE H1 FWY KILAUEA AVE Road Paved 17TH AVE NOEAU ST WAIALAE AVE Road Paved 17TH AVE WAIALAE AVE LUNALILO FWY Road Paved 18TH AVE HARDING AVE DIAMOND HEAD RD Road Paved 19TH AVE H1 FWY KILAUEA AVE Road Paved Full List of Road Paving Projects since 2005 Data Date: Jun 2, 2015 Note: Listing and Status subject to change. -

Morphology of the Te Tumu Cut Under the Potential Re-Diversion of the Kaituna River

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Morphology of the Te Tumu Cut Under the Potential Re-diversion of the Kaituna River A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Earth and Ocean Sciences at The University of Waikato By Joshua Carl Mawer ________ The University of Waikato 2012 i Abstract Following the diversion of the Kaituna River from Maketū Estuary, out to sea at Te Tumu in 1956, the local community has continually voiced concerns over the estuary’s increased sedimentation rates and decreasing ecological health. These concerns led to the partial re-opening of Fords Cut in 1996. However, this has only resulted in a slight improvement in water quality, and no measurable reduction in sedimentation. The Bay of Plenty Regional Council is currently investigating a number of different re-diversion options to partially or fully restore the flow of the Kaituna River into Maketū Estuary, with the aim of restoring the estuary’s health. -

Māori Representation in a Shrunken Parliament

New Zealand Journal of History, 52, 2 (2018) Māori Representation in a Shrunken Parliament IN A REFERENDUM held in conjunction with New Zealand’s 2011 general election, Māori overwhelmingly supported the retention of the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) voting system introduced in 1996. Māori support for MMP was significantly less equivocal than that of the general population.1 The extent of support is understandable. MMP brought many benefits for Māori voters, most obviously a large increase in Māori representation in Parliament.2 The bulk of Māori votes were no longer tied up in just four electorates where they could often be safely ignored. With all votes being equal, political parties had a heightened motivation to pay heed to Māori aspirations and to put forward Māori candidates. The benefits of MMP for Māori were increased through the retention of seats reserved for voters of Māori descent, along with the innovation of linking the number of such seats directly with the numbers enrolled to vote in them. In 1996 the number of Māori seats increased to five under the new rules, and further increased to seven in 2002.3 Previously the number of reserved Māori seats was fixed at four, and had been since 1867.4 New Zealand adopted MMP following a binding referendum held in 1993. In 1990 Ranginui Walker summarized some of the faults with the electoral system then in place, pointing to both historical and ongoing discrimination. Whereas the secret ballot applied in European electorates from 1870, it did not apply in Māori electorates until 1937.5 There were no Māori electoral rolls until 1949 and compulsory voter registration was not introduced for Māori until 1956. -

Lake Wahakari MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS

Lake Wahakari MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS 1. PURPOSE .....................................................................3 2. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................3 3. LAKE LOCATION MAP ..................................................5 4. LAKE OVERVIEW ..........................................................6 5. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL DIMENSION ...........................7 6. PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS ......................................8 7. CHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS .....................................17 8. BIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS ..................................21 9. LAND USE ....................................................................25 10. MONITORING PLAN .....................................................26 11. WORK IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ...................................28 12. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................28 13. APPENDIX 1. GLOSSARY ..............................................29 2 LAKE WAHAKARI MANAGEMENT PLAN | Introduction 1. Purpose LAKE WAHAKARI MANAGEMENT PLAN The purpose of the Outstanding Northland Dune Lakes Management Plans is to implement the recommendations of the Northland Lakes Strategy Part II (NIWA 2014)1. PURPOSE by producing Lakes Management formedPlans, between starting stabilised with sand the dunes 12 along ‘Outstanding’ the west coast, represent a large proportion of warm, lowland valueThe purposelakes ,of and the Outstanding by facilitating Northland actionsDune with mana whenua iwi, landowners and other lakes in New -

Ination# 150150 I[T:I#:L9j:,T:I:-:" S-":,Lf

State of Alaska Nomination Form Department of Fish and Game Anadromous Waters Catalog Division of Sport Fish Region SWT COLD BAY A-2 AWC Number of Water Body 283-32-10100-0010 Name of Water body Old Mans Lagoon E usGS Name n Local Name addition I I oelaiqt n Correction n Backup Information ination# 150150 fur 'lsDate Revision Year: ZA/6 rlq Date "-rlzr Date \iIr{ Date OBSERVATION INFORMATION Species Date(s) Observed Rearing Present Anadromous Chum salmon X E D ! u ! |MPoRTANT:Providea||supportingdocumentationthatthiswaterbodyisimportantforth": numberoffishandlifestagesobserved; samplingmethods,samplingouraiionanoarea""rpLo; copieJoffierd-not"r; !t". ntt""n"-pyofamapshov'ing as \i\€rias other inrormation such ffiL"i4f;XtlXi$:5]fl,;if:r"*"Jt$rifihsnedes, as: specific stream reaches observeo as spawnins or rearins Gomments 283'32'10100listed in AK Peninsula M"""g"r""tArea Satmon sy"tilITlillF- nr""ent due to its simirarity to previousry i[T:i#:l9j:,T:i:-:"_s-":,lf-ly,g,:l"l_".:l_".lrrJ1listed AWC water bodies as either a ,'lake,'or,,polygon,; Name of Observer (please print): Signature: Agency: Address: Thiscertifiesthatinmybest.professiona|judgrnerrtandbe|iefthe"oou included in or deleted from the Anadromous foaters Catalog. Date:_ Revision 11/13 Name of Area Biologist (please print): cFp g& E '= i; e g .s3 H X.= e $i i g E s EHoi 5: P: s''B=: E 6 =3 EE .+:. ! s E.o '= E., o gP i E =O EE .E ! F A sJF'rp P F F i ! g€ * I E! ; ': FO O EP g= ;F:u E-E ig 2 +E P Es F *qi ie gE ; F ! € E gg E E E E € 7,1 s E n -e E:(ca B E =*= 'E E or-. -

Grantees List 2015/2016

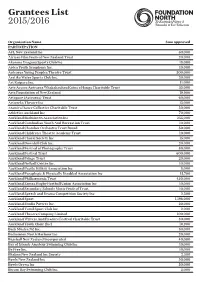

Grantees List 2015/2016 Organisation Name Sum approved PARTICIPATION AFL New Zealand Inc 60,000 African Film Festival New Zealand Trust 20,000 Akarana Dragons Sports Club Inc 18,000 Aotea Youth Symphony Inc. 10,000 Aotearoa Young Peoples Theatre Trust 300,000 Aratika Water Sports Club Inc. 20,000 Art Kaipara Inc. 11,000 Arts Access Aotearoa Whakahauhau Katoa o Hanga Charitable Trust 35,000 Arts Foundation of New Zealand 19,900 Artspace (Aotearoa) Trust 60,000 Artworks Theatre Inc 15,000 Atamira Dance Collective Charitable Trust 50,000 Athletics Auckland Inc 70,000 Auckland Badminton Association Inc 255,000 Auckland Cambodian Youth And Recreation Trust 10,000 Auckland Chamber Orchestra Trust Board 50,000 Auckland Children’s Theatre Academy Trust 10,000 Auckland Choral Society Inc 15,000 Auckland Downhill Club Inc. 20,000 Auckland Festival of Photography Trust 80,000 Auckland Festival Trust 600,000 Auckland Fringe Trust 20,000 Auckland Netball Centre Inc. 10,000 Auckland Pacific Kilikiti Association Inc 8,000 Auckland Paraplegic & Physically Disabled Association Inc 15,700 Auckland Philharmonia Trust 450,000 Auckland Samoa Rugby Football Union Association Inc 10,000 Auckland Secondary Schools Music Festival Trust 10,000 Auckland Speech and Drama Competition Society Inc 2,500 Auckland Sport 1,196,000 Auckland Studio Potters Inc. 20,000 Auckland Tamil Sport Club Inc 2,000 Auckland Theatre Company Limited 100,000 Auckland Writers And Readers Festival Charitable Trust 80,000 Auckland Youth Choir (Inc) 10,900 Bach Musica NZ Inc. 30,000 Badminton North Harbour Inc 20,000 Baseball New Zealand Incorporated 40,000 Bay of Islands Amateur Swimming Club Inc 10,000 Be Free Inc. -

Waitaki District Section Landscape Character Unit ONF to Be Assessed

Natural Features and Natural Landscapes - Waitaki District Section Landscape character unit ONF to be assessed WL1. Waitaki Delta WL1/F1. Waitaki River mouth WL2. Oamaru WL3. Cape Wanbrow WL3/F1. Cape Wanbrow Wave cut notch and fossil beach. WL4. Awamoa WL5. Kakanui WL6. Waianakarua WL6/F1. Bridge Point WL7. Hampden WL7/F1. Moeraki Boulders WL8. Moeraki WL8/F1. Kataki Point WL9. Kataki Beach WL10. Shag Point WL11. Shag River Estuary WL12. Goodwood WL12/F1. Bobbys Head WL13. Pleasant River Estuary 1 WL1. Waitaki Delta Character Description This unit extends from the Otago Region and Waitaki District boundary at the Waitaki River, approximately 20km along the coast to the northern end of Oamaru. This area is the southern part of the outwash fan of the Waitaki River, and the unit extends northwards from the river mouth into the Canterbury Region as well. The coast is erosional and is characterised by a gravel beach backed by a steep consolidated gravel cliff. Nearer the river mouth the delta land surface is lower and there is no coastal cliff. In places, where streams reach the coast, there are steep sided minor ravines that run back from the coast. The land behind is farmed to the clifftop and characterised by pasture, crops and lineal exotic shelter trees. Farm buildings are scattered about but not generally close to the coastal edge. There are a number of gravel extraction sites close to the coast. 2 In the absence of topographical features, the coastal environment has been identified approximately 100m back from the top of the cliff to recognise that coastal influences and qualities extend a small way inland. -

Wairarapa Coastal Habitats Mapping, Risk Assessment and Monitoring

Wriggle coastalmanagement Wairarapa Coastal Habitats Mapping, Risk Assessment and Monitoring Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council January 2007 Wairarapa Coastal Habitats Mapping, Risk Assessment and Monitoring Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: The Gap at Castlepoint, Wairarapa Coast Wriggle Ltd, 148 Hardy St, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph/Fax 03 548 0780, Mob 021 417 936, 021 417 935, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . vii Scope . vii Habitats . vii Issues . viii Monitoring . .viii SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Scope . 1 Structure . 1 SECTION 2 COASTAL HABITAT TYPES 3 Beaches. 3 Dunes and Gravel Berms . .4 Rocky Shores . 5 River Mouth Lagoons (Hapua) . 6 Coastal Lake Estuaries . 7 Tidal River Estuaries . .8 SECTION 3 OWAHANGA ESTUARY TO CASTLEPOINT 9 Beaches and Rocky Shores . 9 Castlepoint Beach . 10 MataikonaEstuary . 11 Okau Estuary . 12 WhakatakiEstuary . 13 SECTION 4 CASTLEPOINT TO WHAREAMA ESTUARY 14 Beaches and Rocky Shores . 14 Ngakauau, Humpies and Otahome River Mouth Lagoons 15 Whareama Estuary . 16 SECTION 5 WHAREAMA ESTUARY TO FLAT POINT 17 Beaches and Rocky Shores . 17 Motuwaireka Estuary . 18 Patanui Estuary (not visited) . 19 Kaiwhata Estuary (not visited) . 20 SECTION 6 FLAT POINT TO PAHAOA 21 Beaches and Rocky Shores . 21 Pahaoa Estuary . 22 SECTION 7 PAHAOA RIVER MOUTH TO CAPE PALLISER 23 Beaches and Rocky Shores . 23 Rerewhakaaitu Estuary . 24 Oterei Estuary . 25 Awhea Estuary (Tora) . 26 Opouawe Estuary (near White Rock) . 27 Wriggle coastalmanagement v SECTION 8 CAPE PALLISER TO WHATARANGI 28 Beaches and Rocky Shores . 28 SECTION 9 PALLISER BAY (WHANGAIMOANA TO OCEAN BEACH 19km) 29 Beaches and Rocky Shores . -

Chandeleur Islands, Louisiana, USA) Were Very Sensitive to the Cross-Island Slopes Imposed by Water-Level Boundary Conditions

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface RESEARCH ARTICLE Inundation of a barrier island (Chandeleur Islands, 10.1002/2013JF003069 Louisiana, USA) during a hurricane: Observed Key Points: water-level gradients and modeled seaward • Water-level measurements recorded across Chandeleur Islands during Isaac sand transport • Higher water levels on bay side caused seaward cross-barrier sand transport Christopher R. Sherwood1, Joseph W. Long2, Patrick J. Dickhudt1, P. Soupy Dalyander2, • Hard-to-observe seaward transport 2 2 deposits are absent in overwash records David M. Thompson , and Nathaniel G. Plant 1U.S. Geological Survey Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA, 2U.S. Geological Survey St. Petersburg Coastal and Marine Science Center, St. Petersburg, Florida, USA Correspondence to: C. R. Sherwood, [email protected] Abstract Large geomorphic changes to barrier islands may occur during inundation, when storm surge exceeds island elevation. Inundation occurs episodically and under energetic conditions that make fi Citation: quantitative observations dif cult. We measured water levels on both sides of a barrier island in the northern Sherwood,C.R.,J.W.Long,P.J.Dickhudt, Chandeleur Islands during inundation by Hurricane Isaac. Wind patterns caused the water levels to slope P. S. Dalyander, D. M. Thompson, and from the bay side to the ocean side for much of the storm. Modeled geomorphic changes during the storm N. G. Plant (2014), Inundation of a barrier island (Chandeleur Islands, Louisiana, USA) were very sensitive to the cross-island slopes imposed by water-level boundary conditions. Simulations during a hurricane: Observed water-level with equal or landward sloping water levels produced the characteristic barrier island storm response of gradients and modeled seaward sand overwash deposits or displaced berms with smoother final topography. -

Significant Coastal Lagoon Systems in the South Island, New Zealand

Significant coastal lagoon systems in the South Island, New Zealand Coastal processes and lagoon mouth closure SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 146 R.M. Kirk and G.A. Lauder Published by Department of Conservation P.O. Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Science for Conservation presents the results of investigations by DOC staff, and by contracted science providers outside the Department of Conservation. Publications in this series are internally and externally peer reviewed. Publication was approved by the Manager, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington. © April 2000, Department of Conservation ISSN 11732946 ISBN 0478219474 Cataloguing-in-Publication data Kirk, R. M. Significant coastal lagoon systems in the South Island, New Zealand : coastal processes and lagoon mouth closure / R.M. Kirk and G.A. Lauder. Wellington, N.Z. :Dept. of Conservation, 2000. 1 v. ; 30 cm. (Science for conservation, 1173-2946 ; 146.) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0478219474 1. LagoonsNew ZealandSouth Island. I. Lauder, G. A. II. Title. Series: Science for conservation (Wellington, N.Z.) ; 146. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. What is a lagoon? 8 2.1 Distinguishing coastal lagoons from estuaries 8 2.2 Definition of types of coastal lagoon 9 2.3 Distribution of coastal lagoons 10 3. Two types of coastal lagoon, South Island, New Zealand 11 3.1 River mouth lagoonshapua 11 3.2 Coastal lakesWaituna-type lagoons 15 3.2.1 Coastal geomorphic character and development 16 3.2.2 Wairau Lagoons 18 3.2.3 Waihora/Lake Ellesmere 18 3.2.4 Waituna Lagoon, Southland 24 3.3 Conclusions 27 4. -

Monitoring Hapua Outlet Dynamics

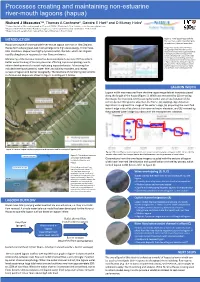

Processes creating and maintaining non-estuarine river-mouth lagoons (hapua) Richard J Measures1,2, Thomas A Cochrane2, Deirdre E Hart3 and D Murray Hicks1 1 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Christchurch, New Zealand. [email protected] 2 Department of Civil and Natural Resources Engineering, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. 3 Department of Geography, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. Figure 3: Time-lapse imagery of the INTRODUCTION Hurunui Hapua with time-linked plots of water level, flow and wave data. Hapua are a type of shore-parallel river-mouth lagoon common in New Zealand. Hapua form where gravel-bed rivers emerge onto high wave energy, micro/meso- Images were recorded every 15 minutes during daylight hours from two cameras tidal coastlines. Hapua have highly dynamic outlet channels, which can migrate located in the center of the lagoon backshore. In the figure, the left hand image is from rapidly alongshore in response to river flows and waves. camera 1 (looking north east), and the right hand image camera 2 (looking south west). Monitoring of the Hurunui Hapua has been conducted since July 2015 to inform Camera location and fields of view are shown better understanding of the key processes affecting hapua morphology and to in Figure 1. Below the animated images the plots show river inflow and lagoon outflow inform development of a model replicating hapua behaviour. Monitoring has (top left), lagoon level and sea level (right), included time-lapse cameras, water level and salinity recorders, and repeat and significant wave height (bottom left). surveys of lagoon and barrier topography.