I'm Going to Go Back There Someday: Reading, Writing, and Directing Hauntings in Four American Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number. -

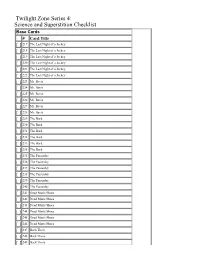

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

The Lonely Page

The Lonely Page Edited by Emily DeDakis © eSharp 2011 eSharp University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ http://www.gla.ac.uk/esharp © eSharp 2011 No reproduction of any part of this publication is permitted without the written permission of eSharp eSharp The Lonely Page Contents Introduction 5 Emily DeDakis, editor (Queen’s University Belfast) Suicide, solitude and the persistent scraping 10 Shauna Busto Gilligan (NUI Maynooth/ University of Glamorgan) Game: A media for modern writers to learn from? 20 Richard Simpson (Liverpool John Moores University) Imaginary ledgers of spectral selves: A blueprint of 29 existence Christiana Lambrinidis (Centre for Creative Writing & Theatre for Conflict Resolution, Greece) ‘The writing is the thing’: Reflections on teaching 36 creative writing Micaela Maftei (University of Glasgow) The solitude room 47 Cherry Smyth (University of Greenwich) How critical reflection affects the work of the writer 55 Ellie Evans (Bath Spa University) Beyond solitude: A poet’s and painter’s collaboration 66 Stephanie Norgate (University of Chichester) & Jayne Sandys-Renton (University of Sussex) Making the Statue Move: Balancing research within 81 creative writing Anne Lauppe-Dunbar (Swansea University, Wales) 3 eSharp The Lonely Page Two inches of ivory: Short-short prose and gender 92 Laura Tansley (University of Glasgow) The beginnings of solitude 102 David Manderson (University of West Scotland) An extract from the novel The Bridge 110 Karen Stevens (University of Chichester) Poems from the sequence Distance 116 Cath Nichols (Lancaster University) An extract from the novel Lost Bodies 120 David Manderson (University of West Scotland) From the poem Now you're a woman 126 Cherry Smyth (University of Greenwich) Parts One, Two and Three 127 Laura Tansley (University of Glasgow) Marthé 134 Barbara A. -

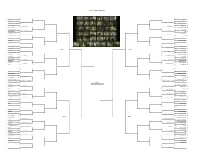

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

HERE PDF Download

iv Beverly Cleary ILLUSTRATED BY Tracy DOckray v iv COntents 1. The New Guests 1 2. The MOtOrcycle 11 3. Trapped! 22 4. Kei th 30 5. Adventure in the Ni ght 46 6. A Peanut Butter Sandwich 64 7. The Vacuum Cleaner 78 8. A Family ReuniOn 94 9. Ralph Takes COmmand 105 10. An AnxiOus Night 119 11. The Search 136 12. An Errand Of Mercy 151 13. A Subject fOr a COmpOsitiOn 164 vii AbOut the AuthOr Other bOOks by Beverly cleary Credits COver COpyright AbOut the Publisher viii 1 The New Guests eith, the boy in the rumpled shorts and K shirt, did not know he was being watched as he entered Room 215 of the Mountain View Inn. Neither did his mother and father, who both looked hot and tired. They had come from Ohio and for five days had driven across plains and deserts and over mountains to the old hotel in the California foothills twenty-five miles from Highway 40. 1 The fourth person entering Room 215 may have known he was being watched, but he did not care. He was Matt, sixty if he was a day, who at the moment was the bellboy. Matt also replaced worn-out lightbulbs, renewed washers in leaky faucets, carried trays for people who telephoned room ser- vice to order food sent to their rooms, and sometimes prevented children from hitting 2 one another with croquet mallets on the lawn behind the hotel. Now Matt’s right shoulder sagged with the weight of one of the bags he was carry- ing.“Here you are, Mr. -

New to Hoopla

New to Hoopla - January 2014 A hundred yards over the rim Audiobook Rod Serling 00:37:00 2013 A most unusual camera Audiobook Rod Serling 00:38:00 2013 A murder in passing Audiobook Mark DeCastrique 08:35:00 2013 A sea of troubles Audiobook P. G. Wodehouse 00:30:00 2013 A short drink from a certain fountain Audiobook Rod Serling 00:39:00 2013 A small furry prayer Audiobook Steven Kotler 09:30:00 2010 A summer life Audiobook Gary Soto 03:51:00 2013 Accelerated Audiobook Bronwen Hruska 10:36:00 2013 American freak show Audiobook Willie Geist 05:00:00 2010 An amish miracle Audiobook Beth Wiseman 10:13:22 2013 An occurrence at owl creek bridge Audiobook Ambrose Bierce 00:28:00 2013 Andrew jackson's america: 1824-1850 Audiobook Christopher Collier 02:03:00 2013 Angel guided meditations for children Audiobook Michelle Roberton-Jones 00:39:00 2013 Animal healing workshop Audiobook Holly Davis 01:01:00 2013 Antidote man Audiobook Jamie Sutliff 08:23:00 2013 Ashes of midnight Audiobook Lara Adrian 10:00:00 2010 At the mountains of madness Audiobook H. P. Lovecraft 04:48:00 2013 Attica Audiobook Garry Kilworth 09:46:00 2013 Back there Audiobook Rod Serling 00:35:00 2013 Below Audiobook Ryan Lockwood 09:52:00 2013 Beyond lies the wub Audiobook Philip K. Dick 00:22:00 2013 Bittersweet love Audiobook Rochelle Alers 06:21:00 2013 Bottom line Audiobook Marc Davis 07:31:00 2013 Capacity for murder Audiobook Bernadette Pajer 07:52:00 2013 Cat in the dark Audiobook Shirley Rousseau Murphy 09:14:00 2013 Cat raise the dead Audiobook Shirley Rousseau Murphy -

The Poetic Theory and Practice of Langston Hughes

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 The Poetic Theory and Practice of Langston Hughes Philip M. Royster Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Royster, Philip M., "The Poetic Theory and Practice of Langston Hughes" (1974). Dissertations. 1439. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1439 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Philip M. Royster THE POETIC THEORY AND PRACTICE OF LANGSTON HUGHES by Philip M. Royster A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 1974 -- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE ii LIFE .. iii Chapter I. THE POETIC THEORY OF LANGSTON HUGHES 1 A. Approach and Capture . 1 B. The Emotion and Rhythm of Experience . 5 c. The Function of Poetry . 18 D. The Nature of the Artist . 39 E. The Intention of the Artist. 48 F. Materials for the Artist . 67 Chapter .II. THE TECHNIQUES OF LANGSTON HUGHES' POETRY • • . 73 A •• The Weary Blues • . • • • • • • • • • 74 B. • Fine Clothes to the Jew • . • • • • • . 120 c. Dear Lovely Death. • • • • • . • • 170 D. The Negro Mother . • • 178 E. The Dream Keeper . -

Season4article.Pdf

N.B.: IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE TWO-PAGE VIEW IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. VIEW/PAGE DISPLAY/TWO-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT) and ENABLE SCROLLING “EVENING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” (minus ‘The’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019 The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Author permissions are required to reprint all or part of this work. www.twilightzonemuseum.com * www.facebook.com/twilightzonemuseum Preface At this late date, little has not been said about The Twilight Zone. It’s often imitated, appropriated, used – but never remotely matched. From its quiet and decisively non-ostentatious beginnings, it steadily grew into its status as an icon and televisional gemstone…and not only changed the way we looked at the world but became an integral part of it. But this isn’t to say that the talk of it has been evenly distributed. Certain elements, and full episodes, of the Rod Serling TV show get much more attention than others. Various characters, plot elements, even plot devices are well-known to many. But I dare say that there’s a good amount of the series that remains unknown to the masses. In particular, there has been very much less talk, and even lesser scholarly treatment, of the second half of the series. This “study” is two decades in the making. It started from a simple episode guide, which still exists. Out of it came this work. The timing is right. In 2019, the series turns sixty years old. -

THE TRIAL of the CHICAGO 7 Written by Aaron Sorkin

THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7 Written by Aaron Sorkin FADE IN: 1 LYNDON JOHNSON addresses a television camera (FILE FOOTAGE) 1 LYNDON JOHNSON I have today ordered to Vietnam the Air Mobile Division and certain other forces which will raise our fighting strength from 75,000 to 125,000 almost immediately. This will make it necessary to increase our active fighting forces by raising the monthly draft from 17,000 to 35,000 per month. MUSIC crashes in that will take us through the prologue--a nation coming off the rails. 2 INT. LOTTERY DRAWING - DAY (FILE FOOTAGE) 2 A few well-scrubbed young men from the Youth Draft Advisory Committee stand over a goldfish bowl containing capsules. One of the young men pulls a capsule and reads it as if someone’s won something-- YOUNG MAN June 3rd. All those whose birthday falls on June 3rd-- 3 INT./EXT MAILBOXES - DAY/NIGHT 3 We see a SERIES OF TIGHT SHOTS of different kinds of mailboxes being opened--rural, suburban, apartment building, etc., all of it under-- REPORTER #1 (V.O.) President Johnson announced new monthly draft totals increasing to 35,000 per month-- REPORTER #2 (V.O.) 43,000 per month-- REPORTER #3 (V.O.) 51,000 per month-- REPORTER #4 (V.O.) 382,386 men between the ages of 18 and 24 have now been called to duty. 2. 4 EXT. RURAL MAILBOX TREE - DAY 4 A line of mailboxes sit on the side of a rural road. One of them is open. We move down and see mail scattered at the feet of a young black man, 18, slumped down on the ground, his induction notice shaking in his hands.