George Bodington 1799-1882

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measuring Points for Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools 2020

Establishment Name Measuring point (Read the note at the bottom of page 4). Adderley Primary School Main entrance on Arden Road Allens Croft Primary School Main entrance to the school building Anderton Park Primary School Main entrance to the school building Anglesey Primary School Main entrance to the school building Arden Primary School Main entrance to the school building Balaam Wood School Centre of the school building Banners Gate Primary School Centre point of the school building Barford Primary School Centre point of the school building Beeches Infant School Main gate of the Perry Beeches site Beeches Junior School Main gate of the Perry Beeches site Bellfield Infant School (NC) Main entrance to the school building Bellfield Junior School Main entrance to the school building Bells Farm Primary School Main entrance to the school building Benson Community School Main entrance to the school building Birches Green Infant School Main entrance to the infant school building Birches Green Junior School School gate off Birches Green Road Blakesley Hall Primary School Main entrance to the school building Boldmere Infant School and Nursery School gate on Cofield Road Boldmere Junior School School gate on Cofield Road Bordesley Green Girls' School & Sixth Form School gate on Bordesley Green Road Bordesley Green Primary School School gate on Drummond Road Broadmeadow Infant School Main entrance to the school building Broadmeadow Junior School Main entrance to the school building Calshot Primary School Main entrance to the school building Chad -

Age-Friendly Tyburn 5-10 Year Plan Final Report

1 Final Report Age-Friendly Tyburn 5-10 Year Plan MARCH 2021 Fig 1 Image Credit: Aging Better Image Library 2 Contents Page Editors Note: Contents and Editors Note 2 The Covid-19 pandemic occurred in the last 4 months of the project and had an impact on the delivery of longer term trials. In reaction to the pandemic, two Executive Summary 3 significant documents have been released: Project Location 4 • Statutory guidance and £250million announcement for temporary infrastructure Project Map 5 changes published by the Department for Transport Age-friendly City Recommendations 6 • Birmingham City Council’s Emergency Transport Plan Section 1 : Project Methodology 7 Both documents look at fast tracking several types of temporary infrastructure to support social distancing. These include: Section 2 : Key Recommendations for an Age-friendly City • Allocation of space for people to walk and cycle - Road Safety 8 • In areas where public transport use is being discouraged, limiting the increase - Placemaking 13 in private motor vehicle use. - Connectivity 17 Many of the measures recommended or suggested in the documents above are those that we have also recommended in this plan. In both cases, the documents - Maintenance 21 have pushed the timescales to deliver changes within a few weeks or months Section 3 : Update to wider planning/context 24 rather than over years. We believe that many of our recommendations will be met through these agendas. Section 4 : Volunteer Engagement 27 ADDITIONAL READING: Section 5 : Stakeholder Engagement 29 https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/emergencytransportplan Section 6 : Conclusion 30 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reallocating-road-space- Section 7 : Appendix 31 in-response-to-covid-19-statutory-guidance-for-local-authorities/traffic- management-act-2004-network-management-in-response-to-covid-19 ` Age-Friendly Tyburn Report March 2021 Fig 2. -

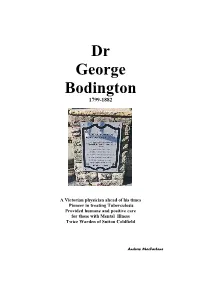

George Bodington 1799-1882

Dr George Bodington 1799-1882 A Victorian physician ahead of his times Pioneer in treating Tuberculosis Provided humane and positive care for those with Mental Illness Twice Warden of Sutton Coldfield Andrew MacFarlane Chapter One INTRODUCTION Overview TB is one of the worst of all diseases to have afflicted humanity. At least 20% of the English population died after contracting TB in the early Nineteenth Century. Very few sufferers expected anything but a hopeless decline. Although the disease was known from prehistoric times, the accepted medical treatments, developed over many hundreds of years, were harsh, unpleasant and rarely successful. They also weakened the bodily strength needed to resist its advances (1) In 1840, George Bodington, a relatively unknown general practitioner from Sutton Coldfield, startled the medical world by publishing an Essay claiming dramatic success in treating patients with TB. He described methods that differed sharply from conventional treatments. Today, Bodington’s Essay has a very special mention in the history of medicine. He was the first recorded physician to use the “fresh air” or “sanatorium method” to treat TB patients. At the time, most critics greeted Bodington’s Essay with scorn. He was so stunned by harsh and humiliating reviews that he eventually gave up treating patients with TB and also retreated from general medical practice. In later life, he did gain some satisfaction from knowing that his ideas and treatment strategies for combatting TB were being accepted and practised. By the 1860s, other pioneering physicians began to adopt the “sanatorium” method, which became the accepted means of treating patients with TB, until the discovery of antibiotics. -

Local Residents C Submissions to the Birmingham City Council Electoral Review

Local Residents C submissions to the Birmingham City Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents with surnames beginning with C. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: PHILIP CALCUTT E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: Dear Review Officer, I am writing support the proposed two-Councillor Moseley Ward and to thank you for taking account of all the representations from people who live in Moseley. It positively demonstrates that the views of local people can be used ti improve decisions. We support the Moseley Society’s proposed minor amendments to the new two councillor Moseley Ward. Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8408 1/1 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: stephen carter E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: I live at please keep as Acocks Green please don't change to Tyseley Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8454 1/1 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: stephen carter E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: Ninfield RD Acocks Green B277TS please keep as Acocks Green please don't change to Tyseley Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8453 1/1 8r Hh x A ) Hhr Hvu xhiruhyss rvr Tr) %Er! % %)"# U) 8r Hh x Tiwrp) AX )@yrpviqh vr -----Original Message----- From: Jane Cassidy Sent: 05 June 2016 10:57 To: reviews <[email protected]> Subject: Election boundaries Dear Sir / Madam I live at I understand that the proposed boundary changes may mean that my property would become part of the Quinton ward. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the East team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Defer – Informal Approval 8 2016/08285/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Demolition of existing extension and stable block, repair and restoration works to Rookery House to convert to 15 no. one & two-bed apartments with cafe/community space. Residential development comprising 40 no. residential dwellinghouses on adjoining depot sites to include demolition of existing structures and any associated infrastructure works. Repair and refurbishment of Entrance Lodge building. Refer to DCLG 9 2016/08352/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Listed Building Consent for the demolition of existing single storey extension, chimney stack, stable block and repair and restoration works to include alterations to convert Rookery House to 15 no. self- contained residential apartments and community / cafe use - (Amended description) Approve - Conditions 10 2017/04018/PA 57 Stoney Lane Yardley Birmingham B25 8RE Change of use of the first floor of the public house and rear detached workshop building to 18 guest bedrooms with external alterations and parking Page 1 of 2 Corporate Director, Economy Approve - Conditions 11 2017/03915/PA 262 High Street Erdington Birmingham B23 6SN Change of use of ground floor retail unit (Use class A1) to hot food takeaway (Use Class A5) and installation of extraction flue to rear Approve - Conditions 12 2017/03810/PA 54 Kitsland Road Shard End Birmingham B34 7NA Change of use from A1 retail unit to A5 hot food takeaway and installation of extractor flue to side Approve - Conditions 13 2017/02934/PA Stechford Retail Park Flaxley Parkway Birmingham B33 9AN Reconfiguration of existing car parking layout, totem structures and landscaping. -

Primary Schools

Appendix 2a Proposed Published Admission Numbers - September 2019 Birmingham City Council (the local authority) is the admissions authority for community and voluntary controlled schools in Birmingham. This document is a record of proposed Published Admission Numbers (PANs) for these schools. A PAN figure for a school does not include places reserved for pupils with a statement of Special Educational Needs (SEN) or an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP). Reserved places are admitted in addition to the PAN. Admission to these reserved places is coordinated through a referral process by the Birmingham City Council Special Educational Needs, Assessment and Review service (SENAR). For a full list of schools offering Resource Base provision please see: Schools with Resource Bases for SEN . Due to the continued changes in Birmingham’s school population as a result of fluctuating birth rates and increased levels of cohort growth, we continue to engage with a number of schools throughout the year to discuss proposed changes to PANs. Any proposed changes to admission numbers or creation of Resource Base places are consulted on as required in accordance with due guidance. Reception Intake - Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools Infant, Primary & All-through Schools DFE PAN PAN No. School Name Sep 2018 Sep 2019 Comments 2010 Adderley Primary School 90 90 2153 Allens Croft Primary School 60 60 2062 Anderton Park Primary School 90 90 2479 Anglesey Primary School 90 90 2300 Arden Primary School 90 90 2026 Banners Gate Primary School 60 60 2014 Barford Primary School 60 60 2017 Beeches Infant School 90 90 2239 Bellfield Infant School (NC) 60 60 2456 Bells Farm Junior and Infant 30 30 School 2435 Benson Community School 60 60 2025 Birches Green Infant School 60 60 2297 Birchfield Community School 90 90 2254 Blakesley Hall Primary School 90 90 2402 Boldmere Infant School & 90 90 Current consultation Nursery underway for a proposed Resource Base at the school. -

Freedom of Information Act 2000

Our ref: 2584033 17 September 2018 David Honey ??? Account reference:[email protected] Freedom of Information Act 2000 Dear Sir I can confirm that the information requested is held by Birmingham City Council. I have detailed below the information that is being released to you. Request I am writing to make a request for the school spend for all primary schools with a Birmingham postcode for academic year September 2017 - July 2018. Response The following figures represent the actual Gross expenditure for the period September 17 to August 18 as requested. It doesn’t reflect the actual published accounts of Birmingham City Council which run on a financial year ending this year in March 2018. The figures therefore do not take account of any accruals for that period of time as BCC do not report on an Academic year and are just the figures in the BCC ledger for the period requested. Information is only available for Birmingham LA schools only. We don’t have other Authority information who have Birmingham post codes such as Solihull. We don’t have any Academy/Free schools financial expenditure. Please contact individual organisations directly. Gross Expenditure Academic year Gross Expenditure Academic year Abbey The RC J & I 2,032,092 Broadmeadow Infant 1,173,387 Adderley J & I 3,056,609 Broadmeadow Junior 1,370,443 Al Furqan 3,177,756 Brookfields Junior & 2,791,680 Allens Croft 2,286,048 Calshot Junior 2,314,339 Anderton Park Junior 3,591,720 Chad Vale Junior & I 2,131,094 PSS Central Strategic Services Birmingham City -

Admissions Arrangments

DETERMINED ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS FOR COMMUNITY AND VOLUNTARY CONTROLLED SCHOOLS FOR 2022 / 2023 ACADEMIC YEAR FOR THE YEAR OF ENTRY AND IN-YEAR ADMISSIONS 1. Birmingham Local Authority (community and voluntary controlled infant, primary and secondary schools) over-subscription criteria 1.1. Any child with an Education, Health and Care Plan is required to be admitted to the school that is named in the plan. This gives such children overall priority for admission to the named school. This is not an oversubscription criterion. The local authority is the admission authority for community and voluntary controlled schools. Children are admitted to schools in accordance with parental preference as far as possible. However, where there are more applications than there are places available, places at community and voluntary controlled schools will be offered based on the following order of priority except those schools set out in paragraphs 2, 3, 4 and 5 below. 1.2. Looked after children or children who were previously looked after (including previously looked after children from outside of England). 1.3. Children with a brother or sister already at the school who will still be in attendance at the time the child enters the school, excluding those children attending nursery, in year 6 or attending a sixth form. 1.4. In the case of Voluntary Controlled Church of England primary schools, children whose parents have made applications on denominational grounds. This will be confirmed by a letter from the Vicar / Minister of the relevant Church. Details of schools that use denominational criteria can be viewed at section 6. -

APPENDIX 1 : WMCA Borrowing Cap Provisionally Agreed with HMT

APPENDIX 1 : WMCA Borrowing Cap Provisionally Agreed With HMT Planned external debt External debt at 31 March Body Function(s) Project Description 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 Existing WMCA External Debt (Including Deductions for Planned Loan Maturities with PWLB, Legacy WM WMCA Transport £172,078,145 £166,218,464 £160,289,728 £136,283,774 £130,199,122 £124,025,763 County Council Maturities and reductions in principal on annuity loans) WMCA Planned Prudential Borrowing from Table Below See Below £0 £0 £78,975,784 £350,296,825 £532,666,835 £743,309,568 Total planned external debt £172,078,145 £166,218,464 £239,265,512 £486,580,599 £662,865,957 £867,335,331 Planned prudential borrowing Prudential borrowing between 1 April and 31 March Project Function(s) Project Description Financing Description 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 Transport / Economic UK Central Interchange Package involves delivery of improvements and interchange capability at the HS2 Devo Deal Investment Programme : UKC Interchange £2,172,240 £18,207,390 £16,113,290 £12,303,330 Regeneration / Highways Interchange station hub. UK Central Infrastructure Package involves delivery local network improvements, public realm and town Transport / Economic centre enhancements, green infrastructure and digital connectivity. These measures will support Devo Deal Investment Programme : UKC Infrastructure £3,544,890 £10,686,250 £25,866,540 £56,719,160 Regeneration / Highways connectivity and access to the HS2 Interchange Station and support economic growth in the UK Central growth zones and corridors. Devo Deal Investment Programme : Metro Birmingham Eastside Extension Transport Extension of the Metro route to the HS2 site to include track and vehicles. -

Three Hundred Years

THREE HUNDRED YEARS OF A FAMILY LIVING, BEING A HISTORY OF THE RII.1ANDS OF SU1'TON Col,DFIELD. BY THE REV. W. K. RILAND BEDFORD, M.A. BIRMINGHAM: CORNISH BROTHERS. 1889. PREF ACE. "Brief let n1e be." It is only the necessity of stating plainly and candidly that the idea of placing family records before the public would never have occurred to the compiler of this book, had not the curiosity evinced by friends and neighbours led hi1n to conclude that a selection from the letters which lay before hi1n might have its use in gratifying the laudable interest now so generally felt in local history and tradition : it is this alone which makes a preface excusable. The greater part of these letters are comprised in the latter half of the last century and the comn1ence1nent of the present, but the predecessors and the successors of the re1narkable family group of the Rilands of Sutton are not unworthy of record for their own sakes, as well as in their relation to the Levitical race, four of whom, fron1 1688 to 1822, were rectors as well as patrons of the "family living." LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. MAP OF SUTTON RECTORY AND GLEBE, 1761 - facing title page. THE RILAND ARMS - page 1. " 16. PORTRAIT OF JOHN RILAND IN BOYHOOD " " PORTRAIT OF RICHARD BISSE RILAND 69. " " PORTRAIT OF JOHN RILAND " ,, I 21. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Purchase from the Crown of the Advowson of Sutton Coldfield.--Rectors under the Earls of Warwick and Tudor sovereigns.-Terrier of Glebe in 1612.-Dr. John Burges presented by Mr. -

Educational Outcome Dashboards Birmingham and Constituency Level

Educational Outcome Dashboards Birmingham and Constituency Level 2018 Examinations and Assessments (Revised) March 2019 Data and Intelligence Team Birmingham City Council [email protected] Primary Phase Covers Headline Measures for Early Years, Key stage 1 and Key stage 2 (revised) Constituency information relates to pupils living in the area at time of school census using their home postcode as reference. Postcodes matched to Ward and Constituency via: https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/geographicalproducts/postcodeproducts Coverage From May 2018 some wards cross constituency boundaries. For purely comparison purposes all wards have been matched to a single constituency based on the highest proportion of children. Ward coverage indicates the amount of children in the ward within the constituency. In the case of constituency, coverage indicates the proportion of it that is made up by the displayed wards. All figures represent all children living in indicated area. 2017 / 2018 Primary phase outcomes for children attending a state school in Birmingham EYFSP Key stage 1 Key stage 1 Key stage 1 Good Level of Development Reading at least expected Writing at least expected Maths at least expected National 72% 75% 70% 76% West Midlands 69% 74% 69% 75% Stat Neighbours 69% 75% 70% 76% Core Cities 68% 72% 66% 73% Birmingham 68% 73% 67% 73% Key stage 2 Key stage 2 Reading average progress Writing average progress Maths average progress Reading, Writing & Maths (EXS+) NationalNational National National 65% West MidlandsWest -

Polling Stations by Electoral Area

Polling Stations by Electoral Area Printed: 31 March 2011 Level: 1W - Ward Area: ACOCKS GREEN PD Stn No Premises Electorate CAA 1 / CAA Yarnfield Primary School, Yarnfield Road, B11 3PJ 1200 CAA 2 / CAA Yarnfield Primary School, Yarnfield Road, B11 3PJ 1381 CAB 3 / CAB Acocks Green Primary School, Warwick Road, B27 7UQ 1794 CAC 4 / CAC Common Room, Coppice House, Pemberley Road, B27 7TA 1221 CAD 5 / CAD Ninestiles Technology College, Hartfield Crescent, B27 7QG 1150 CAE 6 / CAE Lakey Lane Junior and Infant School, Lakey Lane, B28 8RY 1609 CAF 7 / CAF Severne Junior & Infant (NC) School, Severne Road, B27 7HR 1438 CAF 8 / CAF Severne Junior & Infant (NC) School, Severne Road, B27 7HR 1452 CAG 9 / CAG The Oaklands Primary School, Dolphin Lane, B27 7BT 1558 CAG 10 / CAG The Oaklands Primary School, Dolphin Lane, B27 7BT 1471 CAWW 11 / CAWW Cottesbrooke Infants School, (entrance Cottesbrooke Road or), Yardley Road, 1511 B27 6LG CAXX 12 / CAXX Holy Souls Catholic Primary School, Mallard Close, off Warwick Road, B27 6BN 971 CAYY 13 / CAYY Cottesbrooke Junior School, Yardley Road, B27 6JL 2087 CAZZ 14 / CAZZ St. Marys Church Meeting Room, Warwick Road, B27 6QX 940 Electorate / Number of Stations for Area ACOCKS GREEN: 19,783 14 Area: ASTON PD Stn No Premises Electorate CBA 15 / CBA Lozells Methodist Church Centre, 113 Lozells Street, Birmingham, B19 2AP 1180 CBB 16 / CBB St. Georges Infant & Junior School, St Georges Street, B19 3QY 1731 CBB 17 / CBB St. Georges Infant & Junior School, St Georges Street, B19 3QY 1702 CBC 18 / CBC Chilwell Croft