George Bodington 1799-1882

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

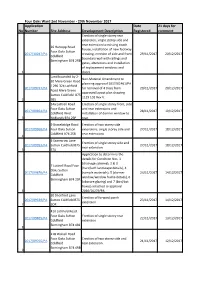

29Th November 2017 No Application Number Site Address Development

Four Oaks Ward 2nd November - 29th November 2017 Application Date 21 days for No Number Site Address Development Description Registered comment Erection of single storey rear extension, single storey side and rear extension to existing coach 26 Hartopp Road house, installation of new footway Four Oaks Sutton 2017/10047/PA crossing, erection of side and front 29/11/2017 20/12/2017 Coldfield boundary wall with railings and Birmingham B74 2RB gates, alterations and installation of replacement windows and 1 doors Land bounded by 2- Non-Material Amendment to 10 Mere Green Road planning approval 2017/02461/PA / 296-324 Lichfield 2017/09747/PA for removal of 4 trees from 29/11/2017 20/12/2017 Road Mere Green approved layout plan drawing Sutton Coldfield B75 1129 101 Rev V. 2 5BS 14a Luttrell Road Erection of single storey front, side Four Oaks Sutton and rear extensions and 2017/09854/PA 28/11/2017 19/12/2017 Coldfield West installation of dormer window to 3 Midlands B74 2SP rear. 9 Bracebridge Road Erection of two storey side 2017/09960/PA Four Oaks Sutton extensions, single storey side and 27/11/2017 18/12/2017 Coldfield B74 2SB rear extensions 4 6 Scarecrow Lane Erection of single storey side and 2017/09953/PA Sutton Coldfield B75 27/11/2017 18/12/2017 rear extension 5 5TU Application to determine the details for Condition Nos. 1 (drainage scheme), 2 & 3 7 Luttrell Road Four (hard/soft landscape details), 4 Oaks Sutton 2017/09876/PA (sample materials), 5 (dormer 23/11/2017 14/12/2017 Coldfield window/window frame details), 6 Birmingham B74 2SR (obscure glazing) and 7 (bird/bat boxes) attached to approval 6 2016/10279/PA 20 Sherifoot Lane Erection of forward porch 2017/09339/PA Sutton Coldfield B75 23/11/2017 14/12/2017 extension. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 15 February 2018

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 15 February 2018 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the South team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Approve - Conditions 8 2017/10544/PA 12 Westlands Road Moseley Birmingham B13 9RH Erection of two storey side and rear and single storey forward and rear extensions Approve - Conditions 9 2017/10199/PA Kings Norton Boys School Northfield Road Kings Norton Birmingham B30 1DY Demolition of existing gymnasium sports hall and erection of replacement sports hall together with changing rooms and storage Page 1 of 1 Corporate Director, Economy Committee Date: 15/02/2018 Application Number: 2017/10544/PA Accepted: 12/12/2017 Application Type: Householder Target Date: 06/02/2018 Ward: Moseley and Kings Heath 12 Westlands Road, Moseley, Birmingham, B13 9RH Erection of two storey side and rear and single storey forward and rear extensions Applicant: Mra Nasim Jan 12 Westlands Road, Moseley, Birmingham, B13 9RH Agent: Mr Hanif Ghumra 733 Walsall Road, Great Barr, Birmingham, B42 1EN Recommendation Approve Subject To Conditions 1. Proposal 1.1. Planning consent is sought for the proposed erection of a two storey side and rear extension and single storey forward and rear extensions. 1.2. The proposed development would provide an extended living room, kitchen/dining room and hallway at ground floor level. The existing garage would be converted to a study with a small extension to this room. At first floor level two new bedrooms and a bathroom would be provided. The existing bathroom would be incorporated into the landing area and the existing third bedroom would become a second bathroom. -

Measuring Points for Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools 2020

Establishment Name Measuring point (Read the note at the bottom of page 4). Adderley Primary School Main entrance on Arden Road Allens Croft Primary School Main entrance to the school building Anderton Park Primary School Main entrance to the school building Anglesey Primary School Main entrance to the school building Arden Primary School Main entrance to the school building Balaam Wood School Centre of the school building Banners Gate Primary School Centre point of the school building Barford Primary School Centre point of the school building Beeches Infant School Main gate of the Perry Beeches site Beeches Junior School Main gate of the Perry Beeches site Bellfield Infant School (NC) Main entrance to the school building Bellfield Junior School Main entrance to the school building Bells Farm Primary School Main entrance to the school building Benson Community School Main entrance to the school building Birches Green Infant School Main entrance to the infant school building Birches Green Junior School School gate off Birches Green Road Blakesley Hall Primary School Main entrance to the school building Boldmere Infant School and Nursery School gate on Cofield Road Boldmere Junior School School gate on Cofield Road Bordesley Green Girls' School & Sixth Form School gate on Bordesley Green Road Bordesley Green Primary School School gate on Drummond Road Broadmeadow Infant School Main entrance to the school building Broadmeadow Junior School Main entrance to the school building Calshot Primary School Main entrance to the school building Chad -

Age-Friendly Tyburn 5-10 Year Plan Final Report

1 Final Report Age-Friendly Tyburn 5-10 Year Plan MARCH 2021 Fig 1 Image Credit: Aging Better Image Library 2 Contents Page Editors Note: Contents and Editors Note 2 The Covid-19 pandemic occurred in the last 4 months of the project and had an impact on the delivery of longer term trials. In reaction to the pandemic, two Executive Summary 3 significant documents have been released: Project Location 4 • Statutory guidance and £250million announcement for temporary infrastructure Project Map 5 changes published by the Department for Transport Age-friendly City Recommendations 6 • Birmingham City Council’s Emergency Transport Plan Section 1 : Project Methodology 7 Both documents look at fast tracking several types of temporary infrastructure to support social distancing. These include: Section 2 : Key Recommendations for an Age-friendly City • Allocation of space for people to walk and cycle - Road Safety 8 • In areas where public transport use is being discouraged, limiting the increase - Placemaking 13 in private motor vehicle use. - Connectivity 17 Many of the measures recommended or suggested in the documents above are those that we have also recommended in this plan. In both cases, the documents - Maintenance 21 have pushed the timescales to deliver changes within a few weeks or months Section 3 : Update to wider planning/context 24 rather than over years. We believe that many of our recommendations will be met through these agendas. Section 4 : Volunteer Engagement 27 ADDITIONAL READING: Section 5 : Stakeholder Engagement 29 https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/emergencytransportplan Section 6 : Conclusion 30 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reallocating-road-space- Section 7 : Appendix 31 in-response-to-covid-19-statutory-guidance-for-local-authorities/traffic- management-act-2004-network-management-in-response-to-covid-19 ` Age-Friendly Tyburn Report March 2021 Fig 2. -

A B Row 7 Aberdeen Street Winson Green 9 Acorn Grove 5 Adams

A B Row 7 Aberdeen Street Winson Green 9 Acorn Grove 5 Adams Street Nechells 1 Adderley Street 1 Addison Road Kings Heath 6 Albert Street City Centre 13 Alcester Road Moseley 13 Aldridge Road Perry Barr 7 Allcock Street Nechells 2 Allison Street Nechells 7 Alston Street City Centre 1 Alum Rock Road 2 Alum Rock Road Saltley 3 Andover Street Nechells 1 Armoury Road Small Heath 1 Arthur Street Small Heath 1 Aston Lane Aston 1 Aston Road Aston 64 Aston Street Nechells 32 Augusta Road Acocks Green 1 Avondale Road Sparkhill 1 Bagot Street Aston 1 Baker Street Sparkhill 2 Bamville Road Ward End 3 Banbury Street Nechells 3 Bank Street Kings Heath 1 Barford Street 1 Barford Street Sparkbrook 2 Barnabas Road Erdington 6 Barr Street Hockley 1 Barwick Street City Centre 11 Bath Passage City Centre 13 Bath Row City Centre 9 Beak Street City Centre 2 Bedford Road Sutton Coldfield 3 Belgrave Middleway Edgbaston 1 Bennetts Hill City Centre 18 Berkley Street City Centre 28 Birchall Street 4 Birchfield Road Handsworth 3 Bishop Street Sparkbrook 5 Bishopsgate Street City Centre 1 Bissell Street Sparkbrook 3 Blucher Street City Centre 3 Bolton Street Nechells 1 Bordesley Street Nechells 1 Bow Street City Centre 21 Bradford Street Sparkbrook 23 Braithwaite Road Sparkbrook 2 Branston Street Hockley 38 Brewery Street Aston 1 Bridge Street City Centre 6 Brighton Road Balsall Heath 1 Brindley Drive City Centre 4 Bristol Road Selly Oak 8 Bristol Road South Longbridge 1 Bristol Road South, Northfield 4 Broad Street City Centre 1 Bromsgrove Street City Centre 2 Browning -

Flooding Survey June 1990 River Tame Catchment

Flooding Survey June 1990 River Tame Catchment NRA National Rivers Authority Severn-Trent Region A RIVER CATCHMENT AREAS En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE HEAD OFFICE Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury. Bristol BS32 4UD W EISH NRA Cardiff Bristol Severn-Trent Region Boundary Catchment Boundaries Adjacent NRA Regions 1. Upper Severn 2. Lower Severn 3. Avon 4. Soar 5. Lower Trent 6. Derwent 7. Upper Trent 8. Tame - National Rivers Authority Severn-Trent Region* FLOODING SURVEY JUNE 1990 SECTION 136(1) WATER ACT 1989 (Supersedes Section 2 4 (5 ) W a te r A c t 1973 Land Drainage Survey dated January 1986) RIVER TAME CATCHMENT AND WEST MIDLANDS Environment Agency FLOOD DEFENCE DEPARTMENT Information Centre NATONAL RIVERS AUTHORrTY SEVERN-TRENT REGION Head Office SAPPHIRE EAST Class N o 550 STREETSBROOK ROAD SOLIHULL cession No W MIDLANDS B91 1QT ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 0 9 9 8 0 6 CONTENTS Contents List of Tables List of Associated Reports List of Appendices References G1ossary of Terms Preface CHAPTER 1 SUMMARY 1.1 Introducti on 1.2 Coding System 1.3 Priority Categories 1.4 Summary of Problem Evaluations 1.5 Summary by Priority Category 1.6 Identification of Problems and their Evaluation CHAPTER 2 THE SURVEY Z.l Introduction 2.2 Purposes of Survey 2.3 Extent of Survey 2.4 Procedure 2.5 Hydrological Criteria 2.6 Hydraulic Criteria 2.7 Land Potential Category 2.8 Improvement Costs 2.9 Benefit Assessment 2.10 Test Discount Rate 2.11 Benefit/Cost Ratios 2.12 Priority Category 2.13 Inflation Factors -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 29 August 2019

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 29 August 2019 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the City Centre team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Determine 9 2018/03004/PA 16 Kent Street Southside Birmingham B5 6RD Demolition of existing buildings and residential-led redevelopment to provide 116 apartments and 2no. commercial units (Use Classes A1-A4, B1(a) and D1) in a 9-12 storey building Page 1 of 1 Director, Inclusive Growth Committee Date: 29/08/2019 Application Number: 2018/03004/PA Accepted: 14/06/2018 Application Type: Full Planning Target Date: 13/09/2018 Ward: Bordesley & Highgate 16 Kent Street, Southside, Birmingham, B5 6RD,, Demolition of existing buildings and residential-led redevelopment to provide 116 apartments and 2no. commercial units (Use Classes A1-A4, B1(a) and D1) in a 9-12 storey building Applicant: Prosperity Developments and the Trustees of the Gooch Estate c/o Agent Agent: PJ Planning Regent House, 156-7 Lower High Street, Stourbridge, DY8 1TS Recommendation Determine Report Back 1. This application formed the subject of a report to your Committee at the meeting on the 20th December 2018, when it was deferred for a site visit, further consideration of additional information submitted and the specialist character of the area. Members may recall that a late objection was received on behalf of Medusa Lodge, which together with a noise report were circulated in advance of the Planning Committee meeting. In addition further public participation letters have been received since the original report was circulated. 2. Subsequently discussions have taken place with the applicant to find a way to address the concerns raised. -

Chapter 11: Signs

Consultation Draft 11 Signs Introduction This Chapter provides summary information on mandatory and informatory signing of cycle facilities and of relevant surface markings. Signing should always be kept to the minimum to reduce street clutter and maintenance costs. Mandatory & Informatory Signing The respective diagram numbers refer to those specified in the Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions (TSRGD), 2002. A new edition of TSRGD will be publishhed in 2015. Careful positioning of signs associated with cycle facilities is required in order to comply with siting requirements, to maximise visibility and to minimise street clutter. Size and illumination requirements for Diags 955, 956 and 957 were relaxed in 2013 to reduce street clutter. Diag. No (TSRGD) Description Details Cycle tracks that are segregated from both Route for cycles only motorised traffic and pedestrians 955 Unsegregated shared Shared pedestrian/cycle route cycle/footways 956 Segregated shhared Shared pedestrian/cycle route cycle/footways 957 Start of with-flow cycle lane Mandatory cycle lane onlyl 958.1 For use with mandatory cycle With-flow cycle lane lane only. Diagram 967 may be used for an advisory lane,. 959.1 71 Consultation Draft Diag. No (TSRGD) Description Details On one-way street with Contra-flow cycle lane mandatory contra-flow cycle lane. 960.1 On one-way street where contra-flow cycling is permitted. It is now permitted Contra-flow cycling (advisory to use the No Entrry Sign 960.2 lane or no lane) Diagram 610 and ‘‘Except Cycles’ plate Diag 954.4 at the start of an unmarkked contraflow. Beneath Diagrams 958.1 and Time qualifying plate 959.1 as appropriate. -

Local Residents C Submissions to the Birmingham City Council Electoral Review

Local Residents C submissions to the Birmingham City Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents with surnames beginning with C. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: PHILIP CALCUTT E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: Dear Review Officer, I am writing support the proposed two-Councillor Moseley Ward and to thank you for taking account of all the representations from people who live in Moseley. It positively demonstrates that the views of local people can be used ti improve decisions. We support the Moseley Society’s proposed minor amendments to the new two councillor Moseley Ward. Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8408 1/1 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: stephen carter E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: I live at please keep as Acocks Green please don't change to Tyseley Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8454 1/1 6/21/2016 Local Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Birm ingham District P ersonal Details: Nam e: stephen carter E-m ail: P ostcode: Organisation Nam e: Comment text: Ninfield RD Acocks Green B277TS please keep as Acocks Green please don't change to Tyseley Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/8453 1/1 8r Hh x A ) Hhr Hvu xhiruhyss rvr Tr) %Er! % %)"# U) 8r Hh x Tiwrp) AX )@yrpviqh vr -----Original Message----- From: Jane Cassidy Sent: 05 June 2016 10:57 To: reviews <[email protected]> Subject: Election boundaries Dear Sir / Madam I live at I understand that the proposed boundary changes may mean that my property would become part of the Quinton ward. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the East team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Defer – Informal Approval 8 2016/08285/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Demolition of existing extension and stable block, repair and restoration works to Rookery House to convert to 15 no. one & two-bed apartments with cafe/community space. Residential development comprising 40 no. residential dwellinghouses on adjoining depot sites to include demolition of existing structures and any associated infrastructure works. Repair and refurbishment of Entrance Lodge building. Refer to DCLG 9 2016/08352/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Listed Building Consent for the demolition of existing single storey extension, chimney stack, stable block and repair and restoration works to include alterations to convert Rookery House to 15 no. self- contained residential apartments and community / cafe use - (Amended description) Approve - Conditions 10 2017/04018/PA 57 Stoney Lane Yardley Birmingham B25 8RE Change of use of the first floor of the public house and rear detached workshop building to 18 guest bedrooms with external alterations and parking Page 1 of 2 Corporate Director, Economy Approve - Conditions 11 2017/03915/PA 262 High Street Erdington Birmingham B23 6SN Change of use of ground floor retail unit (Use class A1) to hot food takeaway (Use Class A5) and installation of extraction flue to rear Approve - Conditions 12 2017/03810/PA 54 Kitsland Road Shard End Birmingham B34 7NA Change of use from A1 retail unit to A5 hot food takeaway and installation of extractor flue to side Approve - Conditions 13 2017/02934/PA Stechford Retail Park Flaxley Parkway Birmingham B33 9AN Reconfiguration of existing car parking layout, totem structures and landscaping. -

Solihull, Warks

656I uai JaqtunN Arjs OLD SILHILLIANS' ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1921 COMMITTE E , 1959 The Silhillian President: H. A. STEELE, 13, Marsh Lane, Solihull, Warks. SOL. 0815 THE MAGAZINE Past President: L. G. HIGHWAY, 113, Dovehouse Lane, Solihull, Warks. Aco. 3963. CEN. OF THE President Elect: C. W. D. COOPER, 8, Herbert Rd., Solihull, Warks. SoL. 2462 OLD SILHILLIANS' ASSOCIATION Hon. Secretary D H. BILLING, 21, Yew Tree Lane, Solihull, Warks. SOL. 4460. MID. 2931. Hon. Editor ARTHUR E. UPTON Asst. Hon. Secretary: P. J. HILL, 103, Buryfield Rd., Solihull, Warks. SOL. 4064 1312, Warwick Road, Copt Heath Hon. Treasurer : H. C. LISSIMAN, Mill Lane, Bentley Heath, Knowle, Warks. Asst. Hon. Treasurer: J. B. CURRALL, " Wayside," Kineton Green Road, Olton, Warks. Aco. 1647 MAY, 1959 No. 10 Finance Secretary: P. J. HILL, 103, Buryfreld Rci,, Solihull, Warks. SoL. 4064 Hon. Subs. Secretary: P. B. L. INSTONE, Langstone Works, Lode Lane, Solihull, Warks. Guild Secretary: R. M. JAMES, 923, Warwick Rd., Solihull, Warks. CEN. 6oio CONTENTS Entertainments Secretary : P. J. HANKS, 2, Cambridge Avenue, Solihull, Warks. SOL. 2470 Accounts and Balance Sheets 27-31 Cricket Secretary: W. M. HOBDAY, 50, Stanton Rd., Shirley, Warks. Sm. 5001 Advertisements 20-92 Golf Secretary : J. B. M. URRY, i, Thornby Ave., Solihull, Warks. SoL. 0102 Births 21 Hockey Secretary: N. I. CUTLER, "Ashtree Cottage", Wadleys Road, Solihull, Clubhouse Extension Warks. SOL. 3480 33-35 Rifle Secretary: J. P. WALLIS, 67, Broad Oaks Rd., Solihull, Warks. SOL. 3725 Commemoration 1958 7-8 Rugby Secretary: J. M. RAE, 112, Widney Lane, Solihull, Warks. SOL. 2313 Cricket Club Report 9-10 Squash Secretary: R. -

'VAR,Ylckshire. DEI 289

COTJBT DIBECTJBY.J 'VAR,YlCKSHIRE. DEI 289 Crocombe George 1Vhitefield, ~Iaiden- Daffern T. M. Spencer rd. Coventry]Davies Geo. Rt.33 Clemens st.Lmngtn head road, Stratford-on-.A.von Dain~Iaj.J.13Albany pl.Stratford-on-A Davies Henry Gilbert Hice, Ladbroke Croft Miss, Saunders hall, Bedworth, Dainton G. 5 Low.Hillmorton rd.Rgby road, Southam 8.0 Kuneaton Dainty Samuel, Holland st. Maney, Davies H.Station rd.,Yylcle Grn.B'ham Crofts Rev. Edmd. Jas. .Alcester Sutton Goldfield, Birmingham Davies Jas. 93 Raclford rd.Leamingtn Crofts Miss, 69 Tachbrook rd.Lmngtn Dainty W.E.Rose cot.Foleshill,Covntry Davies Miss Chaclnor villa, Park road, Crofts Mrs.Fern view, Wolvey,Hinckly Daker Mrs. 9 Beanchamp hl.Leamngtn Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham Crofts Mrs. I Portland st. Leamington Dakeyne Mrs.44 Clarendon sq.Lmngtn Davies Miss, Evesham rcl . .Alcstr.R.S.O Orok.er .M-rs. Hall's croft, Old town, Dalby David, 10 Church hi. Leamngtn Davies :Miss, 27 ·warwick row,Covntry Stratford-on-.Avon Dale Rev. John, .Alcester R.S.O Davies ~Iiss C. 22 Butts, Coventry Croker l\Irs. J. M. 2 Old Town, Strat- Dale J. "\Yoodbine cot. BoJehall,Tmwth Davies M. 12 Hillmorton rd. Rugby ford-on-Avon Dale William, 2 Lansdowne place,War- Davies l\Irs. Hamilton, The Limes, Crompton Thomas, Boswell road, Sut- wick road, Coventry Beauchamp square, Leamington ton Goldfield, Birmingham Dale W.H.13 Richmond rd.Olton,B'hm Davies Rt. 1\f.A.Warwick schl.Warwck Cronin Rev. Charles D.D. St. Peter's Dalglish E. Toft ho. Dunchrch.Rugby Davies T.