Managing Player Load in Professional Rugby Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diploma in Personal Training & Strength

Diploma in Personal Training & Strength & Conditioning Online learning with a world-renowned provider 1 Want to achieve your best? It helps to learn from the best. Welcome to Setanta College, an internationally renowned centre of excellence in all aspects of Strength and Conditioning. Founded in 2006, our passion is to help people to realise their full potential – not through a ‘one size fits all’ approach, but rather through bespoke solutions in which we deliver both the technical and interpersonal skills that enable our people to shine in their careers. We ensure that our students – over 40,000 of them in the past decade – are always at the cutting edge of technology and learn the most current methodologies from some of the most respected professional tutors in sport. contents Come join us – and see what we can achieve together. 2 Become a Personal Trainer 04 Why Setanta? 06 What makes a Setanta student? 07 Course Outline 08 Course Details 09 Fees and How to Apply 10 Our Tutors 11 & 12 Setanta: A Brief History 12 Advisory Board 13 Testimonials 14 contents 3 Become a Personal Trainer Rewarding for you. Empowering for your clients. With a Setanta qualification, you will become a sought-after Professional Becoming a Personal Trainer means that you are joining one of the fastest growing professions in the burgeoning fitness industry. Once qualified, you will be your own boss and be well rewarded for your work. It’s a role perfectly suited to those seeking a flexible lifestyle and a more positive work-life balance. More importantly, though, it’s a profession where you can play a pivotal role in improving the lives of others: educating individuals on the benefits of physical activity; helping them achieve their own fitness goals; and -em powering them to improve their physical health and well-being. -

View Customised Artwork

GROUP 1 IA PERIODICTABLEOFTHEELEMENTS 18 VIIIA 1 1.0079 http://www.periodni.com 2 4.0026 1 H RELATIVE ATOMICMASS(1) Metal Semimetal Nonmetal He PERIOD GROUP IUPAC GROUP CAS Alkalimetal Chalcogenselement HYDROGEN 2 IIA 13 IIIA 14 IVA 15VA 16 VIA 17 VIIA HELIUM 13 3 6.941 4 9.0122 Alkalineearthmetal Halogenselement 5 10.811 6 12.011 7 14.007 8 15.999 9 18.998 10 20.180 ATOMICNUMBER 5 10.811 2 Transitionmetals Noblegas Li Be SYMBOL Lanthanide B C N O F Ne B STANDARDSTATE (25 °C;101kPa) LITHIUM BERYLLIUM BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON BORON Actinide Ne -gas Fe -solid 11 22.990 12 24.305 Hg -liquid Tc -synthetic 13 26.982 14 28.086 15 30.974 16 32.065 17 35.453 18 39.948 3 ELEMENT NAME Na Mg VIIIB Al Si P S Cl Ar SODIUM MAGNESIUM 3 IIIB 4 IVB 5 VB 6 VIB 7 VIIB 8 9 10 11IB 12 IIB ALUMINIUM SILICON PHOSPHORUS SULPHUR CHLORINE ARGON 19 39.098 20 40.078 21 44.956 22 47.867 23 50.942 24 51.996 25 54.938 26 55.845 27 58.933 28 58.693 29 63.546 30 65.38 31 69.723 32 72.64 33 74.922 34 78.96 35 79.904 36 83.798 4 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr POTASSIUM CALCIUM SCANDIUM TITANIUM VANADIUM CHROMIUM MANGANESE IRON COBALT NICKEL COPPER ZINC GALLIUM GERMANIUM ARSENIC SELENIUM BROMINE KRYPTON 37 85.468 38 87.62 39 88.906 40 91.224 41 92.906 42 95.96 43 (98) 44 101.07 45 102.91 46 106.42 47 107.87 48 112.41 49 114.82 50 118.71 51 121.76 52 127.60 53 126.90 54 131.29 5 Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Cd In Sn Sb Te I Xe RUBIDIUM STRONTIUM YTTRIUM ZIRCONIUM NIOBIUM MOLYBDENUM TECHNETIUM RUTHENIUM RHODIUM PALLADIUM SILVER CADMIUM -

Leisure, Health, & Fitness Online Continuing Education

Leisure, Health, & Fitness Online Continuing Education Short courses in S&C, Nutrition, and more... Place yourself at the forefront of the industry 1 Continued learning for career enhancement. Welcome to Setanta College, an internationally renowned Institute of Excellence in all aspects of Fitness, Wellness, and Performance Science. Leading coach/trainer education since 1994, our passion is to help practitioners realise their full potential by delivering both the technical and interpersonal skills that enable them to deliver quality to their companies, clients, and athletes. We ensure that our students - over 55,000 of them in the past decade - are always at the cutting edge of the industry and learn the most current methodologies and training skills from some of the most respected professional lecturers in the industry. contents Defining the Programme and w Introducing the unique Setanta Certificate Setanta College has launched a suite of Setanta Certificate programmes to meet the growing industry demand for continued professional education, not only for performance coaches and rehab practitioners but for managers, skills coaches, athletes, and the general public too. These programmes are unique in that they are amongst the only short courses that carry university level credits along with professional validation by industry bodies. Exp Designed & Validated by Industry Experts & Organisations The Setanta Certificate is awarded by Setanta College as a professional education certificate, each carrying 10 ECTSby Iris credits. Further, each programme has been informed, reviewed, and approved by global sporting organisations and companies - all of whom recognise our unrivalled expertise. intro- duction The Performance Revolution Addressing Performance Gaps Enhance and future-proof your career. -

IEEE SENSORS 2020 Committee

IEEE SENSORS 2020 Committee General Co-Chairs Paddy French, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands Troy Nagle, NC State University, USA Technical Program Co-Chairs Gijs Krijnen, University of Twente, The Netherlands Rolland Vida, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Hungary Treasurer Zeynip Celik-Butler, University of Texas at Arlington, USA Tutorials Co-Chairs Frieder Lucklum, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark Menno Prins, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands Focused Sessions Co-Chairs R. Chris Roberts, University of Texas at El Paso, USA Ashwin Seshia, University of Cambridge, UK Awards Co-Chairs Ravinder Dahiya, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK Svetlana Tatic-Lucic, Lehigh University, USA Young Professionals Co-Chairs Sten Vollebregt, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands Saakshi Dhanekar, Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, India Women in Sensors Co-Chairs Sinéad O’Keeffe, University of Limerick, Ireland Alison Cleary, University of Strathclyde, Scotland, UK Publicity Chair Chris Schober, Honeywell, Inc., USA Industrial Liason Committee Fred Roozeboom, TNO-Holst Centre, The Netherlands Felix Mayer Yu-Cheng Lin Live Demonstration Co-Chairs Behraad Bahreyni, Simon Fraser University, Canada Tao Li, University of Cincinnati, USA SENSORS WTC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 2020October 25-28 2020 , 1 Sensors 2020 Program IEEE SENSORS 2020 Track Chairs Track 1: Sensor Phenomenology, Modeling and Evaluation Sampo Tuukkanen, Tampere University, Finland Mohammad Younis, KAUST, Saudi Arabia -

Anti-Doping Annual Review 2014

The Irish Sports Council ANTI-DOPING ANNUAL REVIEW 2014 www.irishsportscouncil.ie Anti-doping Annual Review 2014 1 STAFF Dr. Úna May Director of Ethics and Participation in Sport Ms. Siobhan Leonard Anti-Doping Manager Ms. Rachel Maguire Anti-Doping Education and Research Executive (January 2014 to present) Ms. Cólleen Devine Anti-Doping Executive Ms. Melissa Cumiskey Anti-Doping Executive Ms. Kathryn Gallagher Anti-Doping Executive (February 2014 to present) IRISH SPORTS COUNCIL Top Floor, Block A West End Office Park Blanchardstown Dublin 15 Ireland Phone +353-1-860 8800 Website www.irishsportscouncil.ie/antidoping Email [email protected] 2 Anti-doping Annual Review 2014 CONTENTS 02 INTRODUCTION 04 FOREWORD 05 BACKGROUND 09 TESTING 16 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH 20 ADMINISTRATION HIGHLIGHTS FOR 2014 23 INTERNATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS FOR 2014 24 THE YEAR AHEAD 25 APPENDIX Anti-doping Annual Review 2014 3 INTRODUCTION Doping threatens the integrity of Authority in preparation for the Sport is an integral part sport and is an ongoing threat Giro d’Italia in June 2014. The to sport and athletes. The Irish Council will continue to collaborate of the culture of Irish Sports Council’s role is to work with our international colleagues people. Sport can raise to promote our vision of clean and intelligence agencies on sport in Ireland. Our aim is to doping activities and trends the hopes and dreams drive and support compliance so that we can ensure that our of a Nation and inspire with the Irish Anti-Doping Rules Programme continues to be one of and prevent doping in sport by the best anti-doping programmes future generations to education, testing, intelligence and in the world. -

Student Catalog Volume I 2019-2020 2019 - 2020 Setanta College Catalog Page | 2

Student Catalog Volume I 2019-2020 2019 - 2020 Setanta College Catalog Page | 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Setanta College Overview.................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Mission Statement ................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Vision Statement ...................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Non-discrimination Statement ............................................................................................... 6 1.4 The Facility .............................................................................................................................. 7 1.5 Learning Management System- Moodle ............................................................................... 7 1.6 Library Resources ................................................................................................................... 8 1.7 Licensure .................................................................................................................................. 8 2.0 Administration ...................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Board of Directors ................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 The Staff .................................................................................................................................. -

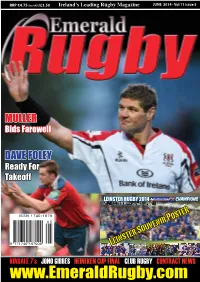

Kearney Injury Setback New Signing: Sean Mccarthy (From Jersey RFC)

RRP €4.75 (inc VAT)/£3.50 Irelandʼs Leading Rugby Magazine JUNE 2014 - Vol 11 issue 5 MULLER Bids Farewell DAVE FOLEY Ready For Takeoff LEINSTER RUGBY 2014 Champions ISSN 1740-1879 The protein you need to raise your game. 05 There are moments in a match when you need to dig deep. During this kind of hard exercise, breakdown happens deep inside your muscle fibres. Cyclone from MaxiNutrition provides creatine to give you the explosive power to go that extra yard, plus the protein your muscles need to recover and rebuild. 9 771740 187009 Leinster Souvenir Poster KINSALE 7’s JONO GIBBES HEINEKEN CUP FINAL CLUB RUGBY CONTRACT NEWS WWW.MAXINUTRITION.COM Protein supports healthy muscles. WWW.MAXINUTRITION.COM MAXINUTRITION, CYCLONE and theStar Device are registered trade marks of the GSK group of companies. www.EmeraldRugby.com Concussion Recognise & Remove Convulsive Unsteady Headache Confused Knocked out Dazed Nauseous Dizzy Any of these - get them off NOW irbplayerwelfare.com/concussion CONTENTS www.emeraldrugby.com JUNE 2014 P16 Dave Foley Set for takeoff P10 Johann Muller bids Ulster farewell LEINSTER RUGBY 2014 Champions P30 Leinster Souvenir Poster P20 Jono Gibbes A Lasting Leinster Legacy P24 Toulon Double Champions of Europe Awards 2014 P48 OTHER FEATURES P36 TEST RUGBY P40 RABODIRECT PRO12 P46 Club & School P28 REFLECTION It’s not always about picking What’s not to love? Notes... Solly talks about his return to the best players northern climes P44 IRELAND RWC BID P38 KINSALE SEVENS Why Ireland need to win the bid P32 BRISTOL REBORN We look back at the action to host the Rugby World Cup Sean Holley on the rebirth of from the 2014 Heineken and should pull out all the stops a great rugby club Kinsale 7’s JUNE 2014 EMERALD RUGBY 1 EDITORIAL: GENERAL NEWS Editors Note What a way for Leinster to finish the season with a fantastic CORRESPONDENCE 34-12 win over Glasgow in the final of the RaboDirect 32 The Slopes, Craigavon, County Armagh, N.Ireland PRO12. -

Draft Terms of Reference

Institutional Review of Setanta College – November 2012 Terms of Reference HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING AWARDS COUNCIL, IRELAND Comhairle na nDámhachtainí Ardoideachais agus Oiliúna, Éire Institutional Review of Providers of Higher Education and Training TERMS OF REFERENCE Setanta College SET www.hetac.ie Page 1 of 10 Institutional Review of Setanta College – November 2012 Terms of Reference Higher Education and Training Awards Council TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW OF Setanta College in November 2012 STATUS: SET Section 1. Purpose The purpose of this document is to specify the Terms of Reference for the Institutional Review of Setanta College in November 2012. The HETAC Institutional Review policy applies to all Colleges providing HETAC accredited programmes, or programmes accredited under Delegated Authority. These Terms of Reference are set within the overarching policy for Institutional Review as approved in December 2007 and should be read in conjunction with same. These Terms of Reference do not replace or supersede the agreed policy for Institutional Review. The Terms of Reference once set may not be amended and any significant revision required to the Terms of Reference will result in a new Terms of Reference to be set by HETAC following consultation with the College. These Terms of Reference should be read in conjunction with the supplementary guidelines for Institutional Review. The objectives of the Institutional Review process are 1. To enhance public confidence in the quality of education and training provided by the College and the standards of the awards made; 2. To contribute to coherent strategic planning and governance in the College; 3. To assess the effectiveness of the Quality Assurance arrangements operated by the College; 4. -

Nuachtlitirmárta 2016

MARCH 2016 NUACHTLITIR MÁRTA 2016 FOR NEWS, VIDEOS AND FIXTURES www.gaa.ie Football Hurling Club General GAA DEFIBRILLATOR SAVED MY LIFE by Cian Murphy t was a Thursday night kick around people suffering instances of cardiac with the lads just like any other. But arrest continue to cause shock among the events of October 11, 2010 would communities around Ireland. change Seaghan Kearney’s life forever. I It’s estimated that every year in Ireland He was playing indoor football in Dublin’s there are 80 such instances which happen St Oliver Plunkett’s Eoghan Ruadha with to people in the 14-35 year-old bracket. club mates when his life was suddenly Only last month Leitrim U21 footballer Alan and scarily turned upside down as this McTigue suffered a cardiac incident and apparently fit and healthy 30 year-old was thankfully survived. Sadly there have been floored by a massive heart attack. many more instances where the results have not been as positive. The quick thinking of his team mates was crucial but, ultimately, it was the presence Initially when Seaghan Kearney dropped of a GAA approved defibrillator on the to the ground his friends thought he had premises, and the availability of a trained slipped. But they soon realised something person who could use it, ensured that this more serious was at play. shocking event didn’t become much more tragic. What happened in the next few critical minutes was where fortune came to “On a Monday night a few of the lads Seaghan’s salvation. would meet and play five a side in the hall in Plunkett’s and that night was the same Working in the club that night as a as any other - only in the middle of the volunteer in the bar was Terry O’Brien – a game my heart stopped and I had a massive trained Paramedic. -

Lgbtireland Report: National Study of the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People in Ireland

GLEN BeLonG To TENI GLEN is a national policy and strategy BeLonG To is the national youth Transgender Equality Network Ireland focused NGO which aims to deliver service for lesbian, gay, bisexual and is a non-profit organisation supporting ambitious and positive change for transgender young people aged between the trans community in Ireland. TENI lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender 14 and 23. BeLonG To’s vision is for an seeks to improve the situation and people in Ireland, ensuring full equality, Ireland where Lesbian Gay bisexual advance the rights and equality of trans inclusion and protection from all forms and transgender (LGBT) young people people and their families. Our Vision of discrimination and harm. We have a are empowered to embrace their is an Ireland where trans people are range of work programmes including development and growth confidently understood, accepted and respected, mental health, education, workplace, and to participate as agents of positive and can participate fully in all aspects of sexual health, families and older people. social change. Irish society. T: +353 1 672 8650 T: +353 1 670 6223 T: +353 1 873 3575 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.glen.ie www.belongto.org www.teni.ie For information on LGBTI services visit www.lgbt.ie For LGBT support call 1890 929 539 LGBTIreland The LGBTIreland Report: national study of the mental health and wellbeing of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people in Ireland Cover_artwork.indd 1 18/03/2016 10:30 Copyright © Agnes Higgins, Louise Doyle, Carmel Downes, Rebecca Murphy, Danika Sharek, Jan DeVries, Thelma Begley, Edward McCann, Fintan Sheerin, Siobháin Smyth; 2016. -

Monitoring Ireland's Skills Supply 1 November 2016

Monitoring Ireland’s Skills Supply Trends in Education and Training Outputs Expert Group on Future Skills Needs c/o Skills and Labour Market Research Unit (SLMRU) SOLAS November 2016 Castleforbes House Castleforbes Road Dublin 1, Ireland Tel: +353 1 533 2464 Email: [email protected] www.skillsireland.ie EGFSN Cover - 152-164 pages cyan+Fas.indd 1 13/06/2014 17:01:04 Monitoring Ireland’s Skills Supply A report by the Skills and Labour Market Research Unit (SLMRU) in SOLAS for the Expert Group on Future Skills Needs 2016 Authors Nora Condon Joan McNaboe Monitoring Ireland's Skills Supply 1 November 2016 Monitoring Ireland's Skills Supply 2 November 2016 Table of contents Foreword 5 Key points 7 1. Introduction 10 2. Skills supply: profile of the population 14 3. Skills supply: education and training outputs 23 4. Science and computing 36 5. Engineering, manufacturing and construction 42 6. Social science, business and law (SSBL) 50 7. Health and welfare 56 8. Services 62 9. Arts and humanities 67 10. Education 73 11. Agriculture and vet 77 Appendix A: Other facts & figures 82 Appendix B: Non-HEA aided higher education providers 83 Monitoring Ireland's Skills Supply 3 November 2016 Monitoring Ireland's Skills Supply 4 November 2016 Foreword Monitoring Ireland’s Skills Supply 2016 is the eleventh in a series of annual publications produced by the Skills and Labour Market Research Unit in SOLAS on behalf of the Expert Group on Future Skills Needs. The Report aims to monitor the potential supply of skills emerging from the education and training system; it also aims to provide a profile of the current skills of the population by education level. -

Sports Strength and Conditioning Sports Strength and Conditioning

Bachelor of Science (Hons) Degree Sports Strength and Conditioning Sports Strength and Conditioning Bachelor of Science (Honours) Degree (Level 8) CAO Programme Code: TI422 NFQ Level: 8 Location: Thurles Number of available places: 50 Duration: 4 Years Application Procedure: Apply to CAO Entry Requirements: • Application will be through the Central Applications Office (CAO) for entry to year 1. • Application for entry to subsequent stages will be through LIT’s admissions office. • Applicants must satisfy a minimum year 1 entry requirement of Grade HC3 in two higher level papers, together with Grade OD3 in four other subjects in the Leaving Certificate Examination to include Mathematics and Irish or English. • Holders of a full FETAC Level 5 award, with a distinction grade in at least three modules or of a full FETAC level 6 award, are also eligible to apply. About the Programme Head of Department: Moya Breen Course Leader: Philip Hennessy Contact the Department of Business, The BSc in Sports Strength and Conditioning is a 4 year programme, built Education and Social Sciences at: around two pillars; Strength and Conditioning, Business and Technology. Email: [email protected] This combination places the course in a unique position within Sports Tel: 0504 28151 courses offered in Ireland. Practical sports strength and conditioning competencies are growing areas of interest and employment nationally and internationally. The Strength and Conditioning coach (S&C coach) is becoming a central and key figure in preparing and advancing the fitness and performance status of the individual athlete and team both in professional sport and also in amateur and recreational sport.