Order No. 2306

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamic Content Delivery Infrastructure Deployment Using Network Cloud Resources

Technische Universität Berlin Fakultät für Elektrotechnik und Informatik Lehrstuhl für Intelligente Netze und Management Verteilter Systeme Dynamic Content Delivery Infrastructure Deployment using Network Cloud Resources vorgelegt von Benjamin Frank (M.Sc.) aus Oldenburg Fakultät IV – Elektrotechnik und Informatik der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften - Dr.-Ing. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Jean-Pierre Seifert, Technische Universität Berlin, Germany Gutachterin: Prof. Anja Feldmann, Ph. D., Technische Universität Berlin, Germany Gutachter: Prof. Bruce M. Maggs, Ph. D., Duke University, NC, USA Gutachter: Prof. Steve Uhlig, Ph. D., Queen Mary, University of London, UK Gutachter: Georgios Smaragdakis, Ph. D., Technische Universität Berlin, Germany Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 16. Dezember 2013 Berlin 2014 D 83 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich versichere an Eides statt, dass ich diese Dissertation selbständig verfasst und nur die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Datum Benjamin Frank (M.Sc.) 3 Abstract Millions of people value the Internet for the content and the applications it makes available. To cope with the increasing end-user demand for popular and often high volume content, e.g., high-definition video or online social networks, massively dis- tributed Content Delivery Infrastructures (CDIs) have been deployed. However, a highly competitive market requires CDIs to constantly investigate new ways to reduce operational costs and improve delivery performance. Today, CDIs mainly suffer from limited agility in server deployment and are largely unaware of network conditions and precise end-user locations, information that improves the efficiency and performance of content delivery. While newly emerging architectures try to address these challenges, none so far considered collaboration, although ISPs have the information readily at hand. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Printmgr File

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K Í ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2019 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 000-17948 ELECTRONIC ARTS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 94-2838567 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 209 Redwood Shores Parkway 94065 Redwood City, California (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (650) 628-1500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Which Registered Annual Report Common Stock, $0.01 par value EA NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes Í No ‘ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ‘ No Í Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Game Streaming Service Onlive Coming to Tablets 8 December 2011, by BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer

Game streaming service OnLive coming to tablets 8 December 2011, By BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer high-definition gaming consoles such as the Xbox 360 and the PlayStation 3. But when they are streamed, the games technically "play" on OnLive's remote servers and are piped onto players' phones, tablets or computers. OnLive users in the U.S. and the U.K. will be able This product image provided by OnLive Inc, shows to use the mobile and tablet service. Games tablets displaying a variety of games using the OnLive available include "L.A. Noire" from Take-Two game controller. OnLive Inc. said Thursday, Dec. 8, Interactive Software Inc. and "Batman: Arkham 2011, that it will now stream console-quality games on City." The games can be played either using the tablets and phones using a mobile application. (AP gadgets' touch screens or via OnLive's game Photo/OnLive Inc.) controller, which looks similar to what's used to play the Xbox or PlayStation. Though OnLive's service has gained traction (AP) -- OnLive, the startup whose technology among gamers, it has yet to reach a mass market streams high-end video games over an Internet audience. connection, is expanding its service to tablets and mobile devices. ©2011 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, OnLive Inc. said Thursday that it will now stream rewritten or redistributed. console-quality games on tablets and phones using a mobile application. Users could already stream such games using OnLive's "microconsole," a cassette-tape sized gadget attached to their TV sets, or on computers. -

Video Games Review DRAFT5-16

Video Games: History, Technology, Industry, and Research Agendas Table of Contents I. Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. Video Game History .................................................................................................. 7 III. Academic Approaches to Video Games ................................................................. 9 1) Game Studies ....................................................................................................................... 9 2) Video Game Taxonomy .................................................................................................... 11 IV. Current Status ........................................................................................................ 12 1) Arcade Games ................................................................................................................... 12 2) Console Games .................................................................................................................. 13 3) PC Standalone Games ...................................................................................................... 14 4) Online Games .................................................................................................................... 15 5) Mobile Games .................................................................................................................... 16 V. Recent Trends .......................................................................................................... -

You Wanted Columns? You Got 'Em>>

FOR FANS OF MUSIC & THOSE WHO MAKE IT Issue 10 • FREE • athensblur.com THESE UNITED STATES • MAD WHISKEY GRIN • BLITZEN TRAPPER • THE DELFIELDS • MEIKO • JANELLE MONAE • TRANCES ARC • DODD FERRELLE • CRACKER & MORE!!! ZERO 7 Acclaimed electronic duo gets haunted on album number four TORTOISE Inspiration be damned — Tortoise soldiers on WHEN You’rE HOT Bradley Cooper’s sizzling Hollywood ride HEART LIFE AT THE SPEED IN haND OF TWEET The latest social media After an eight-year absence, an outlet is changing the music industry, for energized Circulatory System better or for worse returns with a new album VENUE VENTURES Four clubs lead the way into a changing face of Athens music spots YOU WANTED COLUMNS? YOU GOt ‘eM>> SIGN UP AT www.gamey.com/print ENTER CODE: NEWS65 *New members only. Free trial valid in the 50 United States only, and cannot be combined with any other offer. Limit one per household. First-time customers only. Internet access and valid payment method required to redeem offer. GameFly will begin to bill your payment method for the plan selected at sign-up at the completion of the free trial unless you cancel prior to the end of the free trial. Plan prices subject to change. Please visit www.gamey.com/terms for complete Terms of Use. Free Trial Offer expires 12/31/2010. (44) After an eight-year absence, an energized Circulatory System returns with a new HEART album. by Ed Morales IN HAND photos by Jason Thrasher (40) (48) Acclaimed electronic duo Zero 7 gets “haunted” The latest social making album number media outlet is four. -

Postal Regulatory Commission Submitted 12/26/2013 8:00:00 AM Filing ID: 88648 Accepted 12/26/2013

Postal Regulatory Commission Submitted 12/26/2013 8:00:00 AM Filing ID: 88648 Accepted 12/26/2013 BEFORE THE POSTAL REGULATORY COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20268-0001 COMPETITIVE PRODUCT LIST ) Docket No. MC2013-57 ADDING ROUND-TRIP MAILER ) COMPETITIVE PRODUCT PRICES ) Docket No. CP2013-75 ROUND-TRIP MAILER (MC2013-57) ) SUPPLEMENTAL COMMENTS OF GAMEFLY, INC. ON USPS PROPOSAL TO RECLASSIFY DVD MAILERS AS COMPETITIVE PRODUCTS David M. Levy Matthew D. Field Robert P. Davis VENABLE LLP 575 7th Street, N.W. Washington DC 20004 (202) 344-4800 [email protected] Counsel for GameFly, Inc. September 12, 2013 (refiled December 26, 2013) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ..................................................................................1 ARGUMENT .....................................................................................................................5 I. THE POSTAL SERVICE HAS FAILED TO SHOW THAT COMPETITION FOR THE ENTERTAINMENT CONTENT OF RENTAL DVDS, EVEN IF EFFECTIVE TO CONSTRAIN THEIR DELIVERED PRICE, WOULD EFFECTIVELY CONSTRAIN THE PRICE OF THE MAIL INPUT SUPPLIED BY THE POSTAL SERVICE. ..............................................................5 II. THE POSTAL SERVICE’S OWN PRICE ELASTICITY DATA CONFIRM THE ABSENCE OF EFFECTIVE COMPETITION FOR THE MAIL INPUT SUPPLIED BY THE POSTAL SERVICE. ............................................................13 III. THE CORE GROUP OF CONSUMERS WHO STILL RENT DVDS BY MAIL DO NOT REGARD THE “DIGITIZED ENTERTAINMENT CONTENT” AVAILABLE FROM OTHER CHANNELS AS AN ACCEPTABLE -

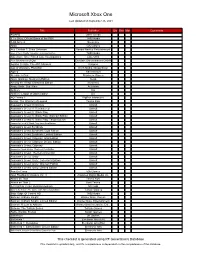

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Electronic Arts Reports Q4 and FY21 Financial Results

Electronic Arts Reports Q4 and FY21 Financial Results Results Above Expectations, Record Annual Operating Cash Flow Driven by Successful New Games, Live Services Engagement, and Network Growth REDWOOD CITY, CA – May 11, 2021 – Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: EA) today announced preliminary financial results for its fiscal fourth quarter and full year ended March 31, 2021. “Our teams have done incredible work over the last year to deliver amazing experiences during a very challenging time for everyone around the world,” said Andrew Wilson, CEO of Electronic Arts. “With tremendous engagement across our portfolio, we delivered a record year for Electronic Arts. We’re now accelerating in FY22, powered by expansion of our blockbuster franchises to more platforms and geographies, a deep pipeline of new content, and recent acquisitions that will be catalysts for further growth.” “EA delivered a strong quarter, driven by live services and Apex Legends’ extraordinary performance. Apex steadily grew through the last year, driven by the games team and the content they are delivering,” said COO and CFO Blake Jorgensen. “Looking forward, the momentum in our existing live services provides a solid foundation for FY22. Combined with a new Battlefield and our recent acquisitions, we expect net bookings growth in the high teens.” Selected Operating Highlights and Metrics • Net bookings1 for fiscal 2021 was $6.190 billion, up 15% year-over-year, and over $600 million above original expectations. • Delivered 13 new games and had more than 42 million new players join our network during the fiscal year. • FIFA 21, life to date, has more than 25 million console/PC players. -

Electronic Arts Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) June 8, 2021 ELECTRONIC ARTS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 0-17948 94-2838567 (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation) (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 209 Redwood Shores Parkway, Redwood City, California 94065-1175 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) (650) 628-1500 (Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. below): ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933(17 CFR §230.405) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (17 CFR §240.12b-2). Emerging growth company ☐ If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or ☐ revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. -

Titanfall 2 Xbox

WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox One™ system, and accessory manuals for important safety and health information. www.xbox.com/support. Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 MULTIPLAYER 5 CONTROLS 3 LIMITED 90-DAY WARRANTY 6 MAIN MENU 4 NEED HELP? 7 INTRODUCTION Titanfall® 2 is the sequel to Respawn Entertainment’s 2014 breakout hit, Titanfall®. In Titanfall 2 ’s Single Player campaign, you play as Jack Cooper—a Militia Rifleman who aspires to become a full-fledged Pilot. Explore the Frontier like never before, brave harsh environments, and forge a powerful bond with your Titan. -

ELECTRONIC ARTS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q þ QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Quarterly Period Ended September 30, 2018 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition Period from to Commission File No. 000-17948 ELECTRONIC ARTS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 94-2838567 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 209 Redwood Shores Parkway Redwood City, California 94065 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (650) 628-1500 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. YES þ NO ¨ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). YES þ NO ¨ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company.