Stigma Toward Worker with Occupational Diseases: a Qualitative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Mobbing in the Workplace and an Overview of Adult Bullying

1: Introduction to Mobbing in the Workplace and an Overview of Adult Bullying Workplace Bullying Clinical and Organizational Perspectives In the early 1980s, German industrial psychologist Heinz Leymann began work in Sweden, conducting studies of workers who had experienced violence on the job. Leymann’s research originally consisted of longitudinal studies of subway drivers who had accidentally run over people with their trains and of banking employees who had been robbed on the job. In the course of his research, Leymann discovered a surprising syndrome in a group that had the most severe symptoms of acute stress disorder (ASD), workers whose colleagues had ganged up on them in the workplace (Gravois, 2006). Investigating this further, Leymann studied workers in one of the major Swedish iron and steel plants. From this early work, Leymann used the term “mobbing” to refer to emotional abuse at work by one or more others. Earlier theorists such as Austrian ethnologist Konrad Lorenz and Swedish physician Peter-Paul Heinemann used the term before Leymann, but Leymann received the most recognition for it. Lorenz used “mobbing” to describe animal group behavior, such as attacks by a group of smaller animals on a single larger animal (Lorenz, 1991, in Zapf & Leymann, 1996). Heinemann borrowed this term and used it to describe the destructive behavior of children, often in a group, against a single child. This text uses the terms “mobbing” and “bullying” interchangeably; however, mobbing more often refers to bullying by more than one person and can be more subtle. Bullying more often focuses on the actions of a single person. -

Overcoming Stigma to Thrive

L. Sookram PhD. Victoria Osler CPWS Mary Ahern CPWS Jen Hazuka CPWS Introductions –Presenters and Panel (8- 10min) Slides and comments (1-9) to Panel (15- 20min) Panel (T-M-J) (10-10-10 min) Summarizing and Strategies (15-20min) Wrap-up questions (10 Min) Participants will : ◦ Learn how to Identify the experiences that led to personal biases about themselves and others with Mental Health Challenges (MHC) ◦ Hear the real life experiences of self stigma and recovery from a peer panel and ◦ Learn about strategies to manage self stigma (archaic ): a scar left by a hot iron : brand : a mark of shame or discredit An identifying mark or characteristic; specifically : a specific diagnostic sign of a disease Examples of stigma in a sentence There's a social stigma attached to receiving welfare. the stigma of slavery remained long after it had been abolished What is mental health stigma?: Mental health stigma can be divided into two distinct types: social stigma is characterized by prejudicial attitudes and discriminating behaviour directed towards individuals with mental health problems as a result of the psychiatric label they have been given. In contrast, perceived stigma or self-stigma is the internalizing by the mental health sufferer of their perceptions of discrimination (Link, Cullen, Struening & Shrout, 1989), and perceived stigma can significantly affect feelings of shame and lead to poorer treatment outcomes (Perlick, Rosenheck, Clarkin, Sirey et al., CLD Graham Ph.D. (2013 post). Mental Health and Stigma. Bias (ˈbaɪəs) n1. mental tendency or inclination, especially an irrational preference or prejudice 2. (Knitting & Sewing) a diagonal line or cut across the weave of a fabric A conviction that a point of view or belief is right for one’s life’s circumstances. -

El Tipo Penal De Mobbing En El Código Penal

EL TIPO PENAL DE MOBBING EN EL CÓDIGO PENAL CARMEN SOTO SUAREZ Licenciada en Derecho. Licenciada en Criminología. Técnico Superior en PRL de las Tres Especialidades RESUMEN La integridad moral es el derecho de toda persona, por el hecho de serlo, a desarrollarse como tal, libremente y en sociedad, derecho que debe ser protegido frente a comportamientos que la humillen, degraden y estigmaticen, entre otros ámbitos, en el laboral. Mediante la LO 5/2012, de 22 de junio, por la que se modifica la LO 10/1995, de 23 de noviembre, del Código Penal, se creó el nuevo delito de Acoso Laboral del artículo 173 CP, sin embargo, este tipo penal es insuficiente ante la variedad de conductas constitutivas de mobbing. Las formas de acoso laboral, solo dependen de la imaginación del acosador, y de su interés en causar sufrimiento. PALABRAS CLAVE Acoso. Intimidación. Mobbing. Violencia psicológica. Violencia física. Acoso sexual. Mobbing inmobiliario. 1 SUMARIO I. INTRODUCCIÓN. LA JURISPRUDENCIA. II. EL TIPO PENAL DE ACOSO LABORAL. III.SUJETO ACTIVO. IV. NECESIDAD DE TIPIFICACIÓN EXPRESA DEL ACOSO LABORAL EN EL ART. 173 DEL CÓDIGO PENAL. DOCTRINA Y JURISPRUDENCIA. V. COMISIÓN POR OMISIÓN. VI. FORMAS DE ACOSO LABORAL. 1- Bossing. 2- Mobbing horizontal. 3-Mobbing ascendente. 4-Mobbing maternal. 5-Violencia en el lugar de trabajo. 6-Síndrome del “chivo expiatorio”. 7-Acoso sexual. 8- Bullying. 9- Ciberbullyin. 10- Network mobbing. 11-Acoso Mediatico. 12-Stalking. 13- Peer Rejection. 14- Gaslighting. 15- Mobbing pasivo (agresión pasiva). 16-Cumplimiento malicioso. 17-Agresión Relacional/Agresión encubierta (Covert aggression). 18-Rankism. 19- Control Freak. 20- Shunting. -

Toward Gender Equality: Progress and Bottlenecks

Chapter 8 Toward Gender Equality: Progress and Bottlenecks Paula England s the significance of gender declining in America? Are men's and women's lives and rewards becoming more similar? To answer this question, I examine trends in market work and unpaid household work, including child care. I consider whether men's and women's employment and hours in paid work are converging, and examine trends in occupational sex segregation and the sex gap in pay. I also consider trends in men's and women's hours of paid work and household work. The emergent picture is one Iof convergence within each of the two areas of paid and unpaid work. Yet progress is not continuous and has stalled recently. Sometimes it continues on one front and stops on another. Gender change is also asymmetric in two ways: things have changed in paid work more than in the household, and women have dramatically increased their participation in formerly "male" activities, but men's inroads into traditionally female occupations or household tasks is very limited by comparison. I consider what these trends portend for the future of gender inequality. Robert Max Jackson argues (see chapter 7, this volume) that continued progress toward gender inequality is inevitable. I agree with him that many forces push in the direction of treating similarly situated men and women equally in bureaucratic organizations. Nonetheless, I conclude that the two related asymmetries in gender change—the sluggish change in the household and in men taking on traditionally female activities in any sphere- create bottlenecks that can dampen if not reverse egalitarian trends. -

Workplace Bullying and Harassment

Law and Policy Remedies for Workplace Bullying in Higher Education: An Update and Further Developments in the Law and Policy John Dayton, J.D., Ed. D.* A dark and not so well kept secret lurks the halls of higher education institutions. Even among people who should certainly know better than to tolerate such abuse, personnel misconduct in the form of workplace bullying remains a serious but largely neglected problem.1 A problem so serious it can devastate academic programs and the people in them. If allowed to maraud unchecked, workplace bullies can poison the office culture; shut down progress and productivity; drive off the most promising and productive people; and make the workplace increasingly toxic for everyone who remains in the bully dominated environment.2 A toxic workplace can even turn deadly when stress begins to take its all too predictable toll on victims’ mental and physical health, or interpersonal stress leads to acts of violence.3 Higher education institutions are especially vulnerable to some of the most toxic forms of workplace bullying. When workplace bullies are tenured professors they can become like bullying zombies seemingly invulnerable to efforts to stop them while faculty, staff, students, and even university administrators run for cover apparently unable or unwilling to do anything about the loose-cannons that threaten to sink them all. This article examines the problem of workplace bullying in higher education; reviews possible remedies; and makes suggestions for law and policy reforms to more effectively address this very serious but too often tolerated problem in higher education. * This article is dedicated to the memory of Anne Proffitt Dupre, Co-Director of the Education Law Consortium, Professor of Law, Law Clerk for the U.S. -

Guide to Acknowledging the Impact of Discrimination, Stigma, and Implicit Bias on Provision of Services

aota.org AOTA’s Guide to Acknowledging the Impact of Discrimination, Stigma, and Implicit Bias on Provision of Services Introduction Protests against racial violence, systemic racism, and the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the longstanding impact of racial discrimination, inequality, and social determinants of health within the American population. Occupational therapy practitioners can address such issues to enhance access to care, improve treatment outcomes, and advocate for equity in service provision for the clients they serve. In addition, recognizing the intersectionality of age, gender identity, sexual orientation, nationality, socioeconomic status, religion, disability, and other forms of social identity is imperative. The following provides an overview of the implications of discrimination, stigma, and implicit bias on provision of occupational therapy services. What is Discrimination? As described by Healthy People 2020, discrimination presents in many forms: Unjust or unfair action Social behaviors that leverage protection of a group in power over those from less privileged groups Promotion of privilege of one group that negatively affects others Discrimination is an important aspect of the social and community context of social determinants of health (Healthy People 2020). With occupation being embedded within context, the various forms of discrimination negatively affect health and well-being. One may experience discrimination based on age, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, disability, and other forms of social identity. Occupational therapy practitioners must support, promote, and advocate for the health and well-being of everyone. See AOTA’s Official Document on Occupational Therapy in the Promotion of Health and Well-Being. Moreover, discrimination affects the occupational therapy process, including evaluation, intervention, and outcomes of occupational therapy service provision. -

Teachers the New Targets of Schoolyard Bullies (2004)

Teachers - the new targets of schoolyard bullies? Jane Benefield Post Primary Teachers Association New Zealand 1. Introduction While murder and mayhem with students running amok with knives and guns may be less prevalent here than in the US or UK, serious assaults against teachers are definitely on the rise1 and violence against teachers is a workplace hazard of increasing concern to PPTA members. There is a great deal of anecdotal evidence available from teachers, and a plethora of stories and articles in the media, particularly high profile stories of physical assaults against teachers from students. This year media coverage of the issue has been dominated by teachers’ reports of workplace bullying at Cambridge High. At meetings held with PPTA members over the last 15 months, teachers report increasing incidents of violence from students. Nor is this a situation where teachers receive either sympathy or support. All too often they report an environment where they are increasingly blamed both for aggressive and disruptive student behaviour and for their efforts to minimise and control it. That blame originates both from within the school community - from management and parents - and also from the very agencies teachers turn to for support, i.e. the Ministry of Education, ERO or the Teachers Council. Despite a wealth of anecdotal evidence, there is currently very little research data available on the prevalence or impact of the various forms of physical and emotional violence directed against staff in schools. Accordingly, in July this year, PPTA undertook a systematic survey of its members in order to find out what kinds of bullying and harassment teachers are facing in schools and from whom. -

Ten Steps to Eliminating Workplace Bullying & Replacing It with A

Creating a Positive Workplace Master Class Catherine Mattice Zundel, MA, SPHR, SHRM-SCP [email protected] 619-454-4489 How to increase your learning: • Turn off everything operating in the background • Turn off your phone, close your door • Interact – ask questions, comment, share, give examples, participate • Introductions • Define bad behaviors • Discuss social phenomenon of negativity • Review myths • Review 10 steps to change • Homework HELLO! • Your Name, Position • Your Company • Your Challenges (i.e., why you’re here) • What is one thing you are looking to get out of this course • A fun fact about yourself Staying Connected • Members Only at CivilityPartners.com • Facebook group • Schedule appointment with me - meetme.so/CatherineMattice How do you know bad behaviors from good? Who decides what’s bad and good? Defining Bad Behaviors Incivility and Bullying Violence Unprofessionalism 1) condition of employment 1) act or threat of 2) severe or pervasive enough physical violence, harassment, that a reasonable person intimidation, or other would consider it threatening disruptive behavior intimidating, hostile, or 2) ranges from threats and verbal abusive abuse to physical assaults and even homicide Discrimination Harassment Mobbing Hazing Bullying • Repeated • Creates psychological power imbalance • Causes harm to targets and witnesses • Costly The Social Phenomenon of Bad Behaviors © Civility Partners/Catherine Mattice • Desire to be seen as uber-competent • Feeling threatened • Stress Low Perceived Costs No polices against behavior No one speaks up against behavior, including peers, management or HR Salin, 2003 Bully Support Support Damage Damage Organizational Organizational Members: Norms, Stressors Power Imbalance Peers, & Culture Management & HR (Reinforcers) Damage Damage Target Three Paradoxes • While virtually all academic researchers and consultants claim that bullying and harassment are organizational problems, advice seems to mostly focus on individual solutions. -

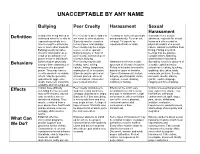

Unacceptable by Any Name

UNACCEPTABLE BY ANY NAME Bullying Peer Cruelty Harassment Sexual Harassment A student is being bullied or Peer Cruelty is when students To annoy or torment repeatedly Any unwelcome sexual Definition victimized when he or she is are mean to other students. and persistently. To wear out: advances, requests for sexual exposed repeatedly over Students may be equals in exhaust. To impede by favors and other verbal or time to negative actions by terms of peer relationships. repeated attacks or raids. physical conduct of a sexual one or more other students. Peer cruelty may be a single nature. Harassment differs from Bullying usually includes severe event or episodic. flirting. Flirting may illicit threat or intimidation as a Bullying may be a form of feelings that are positive, result of an imbalance of peer cruelty, but not all peer complimentary, flattering, power between individuals. cruelty is bullying. wanted and reciprocated. Bullies may be physically Peer cruelty may include Harassment refers to a wide Spreading rumors or pictures of Behaviors stronger than classmates or teasing, name calling, spectrum of offensive behavior. sexually explicit behavior, may perceive personal ridicule, hitting, laughing at, Refers to behavior intended to sexual name calling, touching, power. They may have a making fun of, or exclusion. disturb or upset or threaten. grabbing, dirty jokes, body need to dominate or subdue Students may be picked on, Types of harassment include comments, pictures, threats, others. May be generally shoved, pushed, alone at bullying, psychological ,racial, demands, insults, staring, oppositional, aggressive, recess and not included in religious, sexual, stalking, graffiti, explicit language, tough, hardened, show little peer related activities. -

The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Education Doctoral Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. School of Education 8-2018 The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education Laura Persky St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd Part of the Education Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Persky, Laura, "The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education" (2018). Education Doctoral. Paper 357. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd/357 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education Abstract Current research indicates that workplace bullying exists among a variety of industries in the United States. Further, the reported frequency of workplace bullying appears to be above average in some industries including higher education. Workplace bullying can cause long term harmful effects for the bullied target. Additionally, workplace bullying can create a negative work environment leading to decreased productivity and employee turnover. The purpose of this study was to learn from higher education faculty, administrators, and human resource personnel about their experiences with workplace bullying. This study examined the problem of workplace bullying through different roles and perspectives to better understand how and why it occurs. -

Preventing and Addressing Social Stigma Associated with COVID-19

Social Stigma associated with COVID-19 A guide to preventing and addressing 1 social stigma Target audience: Government, media and local organisations working on the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19). WHAT IS SOCIAL STIGMA? Social stigma in the context of health is the negative association between a person or group of people who share certain characteristics and a specific disease. In an outbreak, this may mean people are labelled, stereotyped, discriminated against, treated separately, and/or experience loss of status because of a perceived link with a disease. Such treatment can negatively affect those with the disease, as well as their caregivers, family, friends and communities. People who don’t have the disease but share other characteristics with this group may also suffer from stigma. The current COVID-19 outbreak has provoked social stigma and discriminatory behaviours against people of certain ethnic backgrounds as well as anyone perceived to have been in contact with the virus. WHY IS COVID-19 CAUSING SO MUCH STIGMA? The level of stigma associated with COVID-19 is based on three main factors: 1) it is a disease that’s new and for which there are still many unknowns; 2) we are often afraid of the unknown; and 3) it is easy to associate that fear with ‘others’. It is understandable that there is confusion, anxiety, and fear among the public. Unfortunately, these factors are also fueling harmful stereotypes. WHAT IS THE IMPACT? Stigma can undermine social cohesion and prompt possible social isolation of groups, which might contribute to a situation where the virus is more, not less, likely to spread. -

AIDS, Mental Illness, and Physical Disability Fatimah Jackson-Best1* and Nancy Edwards2

Jackson-Best and Edwards BMC Public Health (2018) 18:919 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5861-3 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Stigma and intersectionality: a systematic review of systematic reviews across HIV/ AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability Fatimah Jackson-Best1* and Nancy Edwards2 Abstract Background: Stigma across HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability can be co-occurring and may interact with other forms of stigma related to social identities like race, gender, and sexuality. Stigma is especially problematic for people living with these conditions because it can create barriers to accessing necessary social and structural supports, which can intensify their experiences with stigma. This review aims to contribute to the knowledge on stigma by advancing a cross-analysis of HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability stigma, and exploring whether and how intersectionality frameworks have been used in the systematic reviews of stigma. Methods: A search of the literature was conducted to identify systematic reviews which investigated stigma for HIV/ AIDS, mental illness and/or physical disability. The electronic databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, COCHRANE, and PsycINFO were searched for reviews published between 2005 and 2017. Data were extracted from eligible reviews on: type of systematic review and number of primary studies included in the review, study design study population(s), type(s) of stigma addressed, and destigmatizing interventions used. A keyword search was also done using the terms “intersectionality”, “intersectional”,and“intersection”; related definitions and descriptions were extracted. Matrices were used to compare the characteristics of reviews and their application of intersectional approaches across the three health conditions.