Faculty Experiences with Bullying in Higher Education Causes, Consequences, and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Mobbing in the Workplace and an Overview of Adult Bullying

1: Introduction to Mobbing in the Workplace and an Overview of Adult Bullying Workplace Bullying Clinical and Organizational Perspectives In the early 1980s, German industrial psychologist Heinz Leymann began work in Sweden, conducting studies of workers who had experienced violence on the job. Leymann’s research originally consisted of longitudinal studies of subway drivers who had accidentally run over people with their trains and of banking employees who had been robbed on the job. In the course of his research, Leymann discovered a surprising syndrome in a group that had the most severe symptoms of acute stress disorder (ASD), workers whose colleagues had ganged up on them in the workplace (Gravois, 2006). Investigating this further, Leymann studied workers in one of the major Swedish iron and steel plants. From this early work, Leymann used the term “mobbing” to refer to emotional abuse at work by one or more others. Earlier theorists such as Austrian ethnologist Konrad Lorenz and Swedish physician Peter-Paul Heinemann used the term before Leymann, but Leymann received the most recognition for it. Lorenz used “mobbing” to describe animal group behavior, such as attacks by a group of smaller animals on a single larger animal (Lorenz, 1991, in Zapf & Leymann, 1996). Heinemann borrowed this term and used it to describe the destructive behavior of children, often in a group, against a single child. This text uses the terms “mobbing” and “bullying” interchangeably; however, mobbing more often refers to bullying by more than one person and can be more subtle. Bullying more often focuses on the actions of a single person. -

El Tipo Penal De Mobbing En El Código Penal

EL TIPO PENAL DE MOBBING EN EL CÓDIGO PENAL CARMEN SOTO SUAREZ Licenciada en Derecho. Licenciada en Criminología. Técnico Superior en PRL de las Tres Especialidades RESUMEN La integridad moral es el derecho de toda persona, por el hecho de serlo, a desarrollarse como tal, libremente y en sociedad, derecho que debe ser protegido frente a comportamientos que la humillen, degraden y estigmaticen, entre otros ámbitos, en el laboral. Mediante la LO 5/2012, de 22 de junio, por la que se modifica la LO 10/1995, de 23 de noviembre, del Código Penal, se creó el nuevo delito de Acoso Laboral del artículo 173 CP, sin embargo, este tipo penal es insuficiente ante la variedad de conductas constitutivas de mobbing. Las formas de acoso laboral, solo dependen de la imaginación del acosador, y de su interés en causar sufrimiento. PALABRAS CLAVE Acoso. Intimidación. Mobbing. Violencia psicológica. Violencia física. Acoso sexual. Mobbing inmobiliario. 1 SUMARIO I. INTRODUCCIÓN. LA JURISPRUDENCIA. II. EL TIPO PENAL DE ACOSO LABORAL. III.SUJETO ACTIVO. IV. NECESIDAD DE TIPIFICACIÓN EXPRESA DEL ACOSO LABORAL EN EL ART. 173 DEL CÓDIGO PENAL. DOCTRINA Y JURISPRUDENCIA. V. COMISIÓN POR OMISIÓN. VI. FORMAS DE ACOSO LABORAL. 1- Bossing. 2- Mobbing horizontal. 3-Mobbing ascendente. 4-Mobbing maternal. 5-Violencia en el lugar de trabajo. 6-Síndrome del “chivo expiatorio”. 7-Acoso sexual. 8- Bullying. 9- Ciberbullyin. 10- Network mobbing. 11-Acoso Mediatico. 12-Stalking. 13- Peer Rejection. 14- Gaslighting. 15- Mobbing pasivo (agresión pasiva). 16-Cumplimiento malicioso. 17-Agresión Relacional/Agresión encubierta (Covert aggression). 18-Rankism. 19- Control Freak. 20- Shunting. -

Workplace Bullying and Harassment

Law and Policy Remedies for Workplace Bullying in Higher Education: An Update and Further Developments in the Law and Policy John Dayton, J.D., Ed. D.* A dark and not so well kept secret lurks the halls of higher education institutions. Even among people who should certainly know better than to tolerate such abuse, personnel misconduct in the form of workplace bullying remains a serious but largely neglected problem.1 A problem so serious it can devastate academic programs and the people in them. If allowed to maraud unchecked, workplace bullies can poison the office culture; shut down progress and productivity; drive off the most promising and productive people; and make the workplace increasingly toxic for everyone who remains in the bully dominated environment.2 A toxic workplace can even turn deadly when stress begins to take its all too predictable toll on victims’ mental and physical health, or interpersonal stress leads to acts of violence.3 Higher education institutions are especially vulnerable to some of the most toxic forms of workplace bullying. When workplace bullies are tenured professors they can become like bullying zombies seemingly invulnerable to efforts to stop them while faculty, staff, students, and even university administrators run for cover apparently unable or unwilling to do anything about the loose-cannons that threaten to sink them all. This article examines the problem of workplace bullying in higher education; reviews possible remedies; and makes suggestions for law and policy reforms to more effectively address this very serious but too often tolerated problem in higher education. * This article is dedicated to the memory of Anne Proffitt Dupre, Co-Director of the Education Law Consortium, Professor of Law, Law Clerk for the U.S. -

Teachers the New Targets of Schoolyard Bullies (2004)

Teachers - the new targets of schoolyard bullies? Jane Benefield Post Primary Teachers Association New Zealand 1. Introduction While murder and mayhem with students running amok with knives and guns may be less prevalent here than in the US or UK, serious assaults against teachers are definitely on the rise1 and violence against teachers is a workplace hazard of increasing concern to PPTA members. There is a great deal of anecdotal evidence available from teachers, and a plethora of stories and articles in the media, particularly high profile stories of physical assaults against teachers from students. This year media coverage of the issue has been dominated by teachers’ reports of workplace bullying at Cambridge High. At meetings held with PPTA members over the last 15 months, teachers report increasing incidents of violence from students. Nor is this a situation where teachers receive either sympathy or support. All too often they report an environment where they are increasingly blamed both for aggressive and disruptive student behaviour and for their efforts to minimise and control it. That blame originates both from within the school community - from management and parents - and also from the very agencies teachers turn to for support, i.e. the Ministry of Education, ERO or the Teachers Council. Despite a wealth of anecdotal evidence, there is currently very little research data available on the prevalence or impact of the various forms of physical and emotional violence directed against staff in schools. Accordingly, in July this year, PPTA undertook a systematic survey of its members in order to find out what kinds of bullying and harassment teachers are facing in schools and from whom. -

Ten Steps to Eliminating Workplace Bullying & Replacing It with A

Creating a Positive Workplace Master Class Catherine Mattice Zundel, MA, SPHR, SHRM-SCP [email protected] 619-454-4489 How to increase your learning: • Turn off everything operating in the background • Turn off your phone, close your door • Interact – ask questions, comment, share, give examples, participate • Introductions • Define bad behaviors • Discuss social phenomenon of negativity • Review myths • Review 10 steps to change • Homework HELLO! • Your Name, Position • Your Company • Your Challenges (i.e., why you’re here) • What is one thing you are looking to get out of this course • A fun fact about yourself Staying Connected • Members Only at CivilityPartners.com • Facebook group • Schedule appointment with me - meetme.so/CatherineMattice How do you know bad behaviors from good? Who decides what’s bad and good? Defining Bad Behaviors Incivility and Bullying Violence Unprofessionalism 1) condition of employment 1) act or threat of 2) severe or pervasive enough physical violence, harassment, that a reasonable person intimidation, or other would consider it threatening disruptive behavior intimidating, hostile, or 2) ranges from threats and verbal abusive abuse to physical assaults and even homicide Discrimination Harassment Mobbing Hazing Bullying • Repeated • Creates psychological power imbalance • Causes harm to targets and witnesses • Costly The Social Phenomenon of Bad Behaviors © Civility Partners/Catherine Mattice • Desire to be seen as uber-competent • Feeling threatened • Stress Low Perceived Costs No polices against behavior No one speaks up against behavior, including peers, management or HR Salin, 2003 Bully Support Support Damage Damage Organizational Organizational Members: Norms, Stressors Power Imbalance Peers, & Culture Management & HR (Reinforcers) Damage Damage Target Three Paradoxes • While virtually all academic researchers and consultants claim that bullying and harassment are organizational problems, advice seems to mostly focus on individual solutions. -

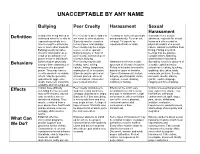

Unacceptable by Any Name

UNACCEPTABLE BY ANY NAME Bullying Peer Cruelty Harassment Sexual Harassment A student is being bullied or Peer Cruelty is when students To annoy or torment repeatedly Any unwelcome sexual Definition victimized when he or she is are mean to other students. and persistently. To wear out: advances, requests for sexual exposed repeatedly over Students may be equals in exhaust. To impede by favors and other verbal or time to negative actions by terms of peer relationships. repeated attacks or raids. physical conduct of a sexual one or more other students. Peer cruelty may be a single nature. Harassment differs from Bullying usually includes severe event or episodic. flirting. Flirting may illicit threat or intimidation as a Bullying may be a form of feelings that are positive, result of an imbalance of peer cruelty, but not all peer complimentary, flattering, power between individuals. cruelty is bullying. wanted and reciprocated. Bullies may be physically Peer cruelty may include Harassment refers to a wide Spreading rumors or pictures of Behaviors stronger than classmates or teasing, name calling, spectrum of offensive behavior. sexually explicit behavior, may perceive personal ridicule, hitting, laughing at, Refers to behavior intended to sexual name calling, touching, power. They may have a making fun of, or exclusion. disturb or upset or threaten. grabbing, dirty jokes, body need to dominate or subdue Students may be picked on, Types of harassment include comments, pictures, threats, others. May be generally shoved, pushed, alone at bullying, psychological ,racial, demands, insults, staring, oppositional, aggressive, recess and not included in religious, sexual, stalking, graffiti, explicit language, tough, hardened, show little peer related activities. -

The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Education Doctoral Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. School of Education 8-2018 The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education Laura Persky St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd Part of the Education Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Persky, Laura, "The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education" (2018). Education Doctoral. Paper 357. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd/357 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Perceived Effects of Organizational Culture on Workplace Bullying in Higher Education Abstract Current research indicates that workplace bullying exists among a variety of industries in the United States. Further, the reported frequency of workplace bullying appears to be above average in some industries including higher education. Workplace bullying can cause long term harmful effects for the bullied target. Additionally, workplace bullying can create a negative work environment leading to decreased productivity and employee turnover. The purpose of this study was to learn from higher education faculty, administrators, and human resource personnel about their experiences with workplace bullying. This study examined the problem of workplace bullying through different roles and perspectives to better understand how and why it occurs. -

The Victim's Experience As Described in Civil Court Judgments for Mobbing

Original Article KOME − An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry The Victim’s Experience as Volume 7 Issue 2, p. 57-73. © The Author(s) 2019 Described in Civil Court Reprints and Permission: [email protected] Judgments for Mobbing: A Published by the Hungarian Communication Studies Association Gender Difference DOI: 10.17646/KOME.75672.39 Daniela Acquadro Maran1, Antonella Varetto2, Matti Ullah Butt3 and Cristina Civilotti1 1 Department of Psychology, University of Turin, ITALY 2 City of Health and Science University Hospital, Turin, ITALY 3 Department of Business Administration, National College of Business Administration and Economics, PAKISTAN Abstract: The aim of this work is to provide a descriptive analysis of the mobbing phenomenon found in a sampling of Italian civil court judgments in the last fifteen years. The analysis was conducted according to the behaviors that characterize the mobbing, the type of workplace, the power differential between perpetrator and victim, the victim’s and the perpetrator’s typologies, the motives, and the consequences for the victim. Data were gathered from two free websites on civil judgments involving mobbing. An analysis of the 73 civil judgments showed 34 male victims (46.6%) and 39 female victims (53.4%) of mobbing. In 68 (93.2%) cases, the behavior that characterized the mobbing campaign was an attack on personal and professional life. Female victims of mobbing in particular indicated isolation and attack on reputation. About half of the sample worked in a private company, 16 (21.9%) in public administration, 11 (15.1%) in the educational sector, and nine (12.3%) in the health sector. -

A Scale of Mobbing Impacts

Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice - 12(1) • Winter • 237-240 ©2012 Educational Consultancy and Research Center www.edam.com.tr/estp A Scale of Mobbing Impacts Erkan YAMANa Sakarya University Abstract The aim of this research was to develop the Mobbing Impacts Scale and to examine its validity and reliability analyses. The sample of study consisted of 509 teachers from Sakarya. In this study construct validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliabilities and item analysis of the scale were examined. As a result of factor analysis for construct validity three factors emerged which named organizational behavior, individual effect, and learned resourcefulness consisting of 29 items which accounted for the 57 % of the total variance. The internal consist- ency reliability coefficients were .92 for organizational behavior, .83 for individual effect, and .63 for learned resourcefulness. The findings also demonstrated that item-total correlations ranged from .32 to .92. Test-retest reliability coefficients were .53 and .89 for three subscales, respectively. According to these findings the Mob- bing Impact Scale can be named as a valid and reliable instrument that could be used in the field of organization. Key Words Mobbing’s Effects, Validity, Reliability. The concept of mobbing was used to define the Victims are exposed to systematic humiliation and behaviors of animals frightening away a thread or their personal rights are held during the mobbing a hunting enemy in 1960s (Lorenz, 2008). For in- process. There are some immoral and hostile behav- stance, Lorenz observed that a goose cannot attack iors towards the victim and it is expected mobbing a fox on its own, but in case a lot of geese come to- occur quite often (at least once a week) or in long gether to join their forces, they can frighten away term (at least six months) (Leymann & Gustafsson, and even injure a fox (Dökmen, 2008) . -

Bullying at Work

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR RESEARCH WORKING PAPER BULLYING AT WORK Social Affairs Series SOCI 108 EN This document is available in the following languages: EN (original) DE, FR The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy. At the end of this document please find a full list of the other publications in the Social Affairs Series Publisher: European Parliament L-2929 Luxembourg Authors: Frank LORHO Ulrich HILP Editor: Lothar BAUER Division for Social and Legal Affairs Directorate-General for Research Tel. 00352 4300 22575 Fax: 00352 4300 27720 E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript completed in August 2001. EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR RESEARCH WORKING PAPER BULLYING AT WORK Social Affairs Series SOCI 108 EN 8 - 2001 Bullying at Work CONTENTS Page Part I: Introduction......................................................................................................... 5 1. Aim and contents of the study........................................................................................ 5 2. Definition of workplace bullying ................................................................................... 5 2.1. Terminology......................................................................................................... -

Mobbing in the Workplace and Individualism: Antibullying Legislation in the United States, Europe and Canada

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Economics Faculty Publications Economics 8-2008 Mobbing in the Workplace and Individualism: Antibullying Legislation in the United States, Europe and Canada M. Neil Browne Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Mary Allison Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/econ_pub Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Browne, M. Neil and Smith, Mary Allison, "Mobbing in the Workplace and Individualism: Antibullying Legislation in the United States, Europe and Canada" (2008). Economics Faculty Publications. 5. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/econ_pub/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. NEIL BROWNE 8/8/2008 12:54:42 PM MOBBING IN THE WORKPLACE: THE LATEST ILLUSTRATION OF PERVASIVE INDIVIDUALISM IN AMERICAN LAW BY ∗ ∗∗ M. NEIL BROWNE AND MARY ALLISON SMITH I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................131 II. WHAT IS MOBBING? ....................................................................131 III. LEGISLATIVE RESPONSES TO MOBBING OUTSIDE THE U.S..................................................................................................134 IV. U.S. APPROACHES TO BULLYING..............................................145 Table 1..............................................................................148 V. CONCLUSION.................................................................................156 -

Redalyc.FORMS of DESTRUCTIVE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE

Independent Journal of Management & Production E-ISSN: 2236-269X [email protected] Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo Brasil Vveinhardt, Jolita; Kuklyte, Jurate FORMS OF DESTRUCTIVE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE EMPLOYEES: HOW MANY ARE THERE AND WHAT IS THE EXTENT OF THE SPREAD? Independent Journal of Management & Production, vol. 8, núm. 1, enero-marzo, 2017, pp. 205-231 Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo Avaré, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=449549996015 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT & PRODUCTION (IJM&P) http://www.ijmp.jor.br v. 8, n. 1, January - March 2017 ISSN: 2236-269X DOI: 10.14807/ijmp.v8i1.532 FORMS OF DESTRUCTIVE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE EMPLOYEES: HOW MANY ARE THERE AND WHAT IS THE EXTENT OF THE SPREAD? Jolita Vveinhardt Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania E-mail: [email protected] Jūratė Kuklytė Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania E-mail: [email protected] Submission: 31/08/2016 Accept: 01/09/2016 ABSTRACT The article presents various forms of destructive behaviour of employees, briefly introducing their key features. The main idea of this article is to carry out a comparative analysis of studies after discussing the forms of destructive behaviour of employees. Results of quantitative and qualitative research published in 2006-2016 have been compared. Results of studies of destructive relationships between employees in the work environment of organizations providing public services have been reviewed.