The Long Non-Coding RNA GHSROS Reprograms Prostate Cancer Cell Lines Toward a More Aggressive Phenotype

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deregulated Gene Expression Pathways in Myelodysplastic Syndrome Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Leukemia (2010) 24, 756–764 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/leu ORIGINAL ARTICLE Deregulated gene expression pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome hematopoietic stem cells A Pellagatti1, M Cazzola2, A Giagounidis3, J Perry1, L Malcovati2, MG Della Porta2,MJa¨dersten4, S Killick5, A Verma6, CJ Norbury7, E Hellstro¨m-Lindberg4, JS Wainscoat1 and J Boultwood1 1LRF Molecular Haematology Unit, NDCLS, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK; 2Department of Hematology Oncology, University of Pavia Medical School, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; 3Medizinische Klinik II, St Johannes Hospital, Duisburg, Germany; 4Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 5Department of Haematology, Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth, UK; 6Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA and 7Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK To gain insight into the molecular pathogenesis of the the World Health Organization.6,7 Patients with refractory myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), we performed global gene anemia (RA) with or without ringed sideroblasts, according to expression profiling and pathway analysis on the hemato- poietic stem cells (HSC) of 183 MDS patients as compared with the the French–American–British classification, were subdivided HSC of 17 healthy controls. The most significantly deregulated based on the presence or absence of multilineage dysplasia. In pathways in MDS include interferon signaling, thrombopoietin addition, patients with RA with excess blasts (RAEB) were signaling and the Wnt pathways. Among the most signifi- subdivided into two categories, RAEB1 and RAEB2, based on the cantly deregulated gene pathways in early MDS are immuno- percentage of bone marrow blasts. -

Iron Transport Proteins: Gateways of Cellular and Systemic Iron Homeostasis

Iron transport proteins: Gateways of cellular and systemic iron homeostasis Mitchell D. Knutson, PhD University of Florida Essential Vocabulary Fe Heme Membrane Transport DMT1 FLVCR Ferroportin HRG1 Mitoferrin Nramp1 ZIP14 Serum Transport Transferrin Transferrin receptor 1 Cytosolic Transport PCBP1, PCBP2 Timeline of identification in mammalian iron transport Year Protein Original Publications 1947 Transferrin Laurell and Ingelman, Acta Chem Scand 1959 Transferrin receptor 1 Jandl et al., J Clin Invest 1997 DMT1 Gunshin et al., Nature; Fleming et al. Nature Genet. 1999 Nramp1 Barton et al., J Leukocyt Biol 2000 Ferroportin Donovan et al., Nature; McKie et al., Cell; Abboud et al. J. Biol Chem 2004 FLVCR Quigley et al., Cell 2006 Mitoferrin Shaw et al., Nature 2006 ZIP14 Liuzzi et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008 PCBP1, PCBP2 Shi et al., Science 2013 HRG1 White et al., Cell Metab DMT1 (SLC11A2) • Divalent metal-ion transporter-1 • Former names: Nramp2, DCT1 Fleming et al. Nat Genet, 1997; Gunshin et al., Nature 1997 • Mediates uptake of Fe2+, Mn2+, Cd2+ • H+ coupled transporter (cotransporter, symporter) • Main roles: • intestinal iron absorption Illing et al. JBC, 2012 • iron assimilation by erythroid cells DMT1 (SLC11A2) Yanatori et al. BMC Cell Biology 2010 • 4 different isoforms: 557 – 590 a.a. (hDMT1) Hubert & Hentze, PNAS, 2002 • Function similarly in iron transport • Differ in tissue/subcellular distribution and regulation • Regulated by iron: transcriptionally (via HIF2α) post-transcriptionally (via IRE) IRE = Iron-Responsive Element Enterocyte Lumen DMT1 Fe2+ Fe2+ Portal blood Enterocyte Lumen DMT1 Fe2+ Fe2+ Fe2+ Fe2+ Ferroportin Portal blood Ferroportin (SLC40A1) • Only known mammalian iron exporter Donovan et al., Nature 2000; McKie et al., Cell 2000; Abboud et al. -

ZMYND10 Functions in a Chaperone Relay During Axonemal Dynein Assembly

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/233718; this version posted December 13, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 ZMYND10 functions in a chaperone relay during axonemal dynein assembly. 2 3 Girish R Mali1,9 , Patricia Yeyati1, Seiya Mizuno2, Margaret A Keighren1, Petra zur Lage3, Amaya 4 Garcia-Munoz4, Atsuko Shimada5, Hiroyuki Takeda5, Frank Edlich6, Satoru Takahashi2,7, Alex von 5 Kreigsheim4,8, Andrew Jarman3 and Pleasantine Mill1,*. 6 7 1. MRC Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of 8 Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, EH4 2XU 9 2. Laboratory Animal Resource Centre, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan, 305-8575 10 3. Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, EH8 9XD 11 4. Systems Biology Ireland, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland 12 5. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan, 113-0033 13 6. Institute for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 14 79104 15 7. Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, 16 Japan, 305-8575 17 8. Edinburgh Cancer Research UK Centre, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University 18 of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, EH4 2XU 19 9. Current address: MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK, CB2 0QH 20 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/233718; this version posted December 13, 2017. -

Ferroportin Mutation in Autosomal Dominant Hemochromatosis: Loss of Function, Gain in Understanding

Ferroportin mutation in autosomal dominant hemochromatosis: loss of function, gain in understanding Robert E. Fleming, William S. Sly J Clin Invest. 2001;108(4):521-522. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI13739. Commentary Normal iron homeostasis requires close matching of dietary iron absorption with body iron needs (1). Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), a common abnormality of iron metabolism, is characterized by excess absorption of dietary iron despite elevated stores, and secondary damage to the liver, pancreas, and other organs (2). Classic HH is caused by mutation of the HFE gene and is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. However, a substantial percentage of individuals with hemochromatosis, especially in non–Northern European populations, have no mutations in HFE (3). Many such cases differ from classic HH in the relative distribution of iron between the plasma, hepatocytes, and reticuloendothelial (RE) cells (4). Pietrangelo et al. recently reported a pedigree with atypical hemochromatosis inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (5). In this issue of the JCI, Montosi et al. report the surprising finding that the gene mutated in these patients (SLC11A3) encodes the iron export protein ferroportin1 (also known as IREG1, or MTP1) (6). They conclude that the identified mutation (A77D) probably results in loss of ferroportin1 function, suggesting that the affected individuals are haploinsufficient for this gene product. In a nearly simultaneous report, Njajou et al. (7) describe a similar pedigree with autosomal dominant hemochromatosis and a different missense mutation (N144H) in the same gene. Njajou et al., however, conclude that the iron overload phenotype was likely […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/13739/pdf Ferroportin mutation in autosomal Commentary dominant hemochromatosis: loss See related article, pages 619–623. -

Environmental Influences on Endothelial Gene Expression

ENDOTHELIAL CELL GENE EXPRESSION John Matthew Jeff Herbert Supervisors: Prof. Roy Bicknell and Dr. Victoria Heath PhD thesis University of Birmingham August 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Tumour angiogenesis is a vital process in the pathology of tumour development and metastasis. Targeting markers of tumour endothelium provide a means of targeted destruction of a tumours oxygen and nutrient supply via destruction of tumour vasculature, which in turn ultimately leads to beneficial consequences to patients. Although current anti -angiogenic and vascular targeting strategies help patients, more potently in combination with chemo therapy, there is still a need for more tumour endothelial marker discoveries as current treatments have cardiovascular and other side effects. For the first time, the analyses of in-vivo biotinylation of an embryonic system is performed to obtain putative vascular targets. Also for the first time, deep sequencing is applied to freshly isolated tumour and normal endothelial cells from lung, colon and bladder tissues for the identification of pan-vascular-targets. Integration of the proteomic, deep sequencing, public cDNA libraries and microarrays, delivers 5,892 putative vascular targets to the science community. -

Supporting Online Material

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Supplementary Information for 8 9 Fractalkine-induced microglial vasoregulation occurs within the retina and is altered early in diabetic 10 retinopathy 11 12 *Samuel A. Mills, *Andrew I. Jobling, *Michael A. Dixon, Bang V. Bui, Kirstan A. Vessey, Joanna A. Phipps, 13 Ursula Greferath, Gene Venables, Vickie H.Y. Wong, Connie H.Y. Wong, Zheng He, Flora Hui, James C. 14 Young, Josh Tonc, Elena Ivanova, Botir T. Sagdullaev, Erica L. Fletcher 15 * Joint first authors 16 17 Corresponding author: 18 Prof. Erica L. Fletcher. Department of Anatomy & Neuroscience. The University of Melbourne, Grattan St, 19 Parkville 3010, Victoria, Australia. 20 Email: [email protected] ; Tel: +61-3-8344-3218; Fax: +61-3-9347-5219 21 22 This PDF file includes: 23 24 Supplementary text 25 Figures S1 to S10 26 Tables S1 to S7 27 Legends for Movies S1 to S2 28 SI References 29 30 Other supplementary materials for this manuscript include the following: 31 32 Movies S1 to S2 33 34 35 36 1 1 Supplementary Information Text 2 Materials and Methods 3 Microglial process movement on retinal vessels 4 Dark agouti rats were anaesthetized, injected intraperitoneally with rhodamine B (Sigma-Aldrich) to label blood 5 vessels and retinal explants established as described in the main text. Retinal microglia were labelled with Iba-1 6 and imaging performed on an inverted confocal microscope (Leica SP5). Baseline images were taken for 10 7 minutes, followed by the addition of PBS (10 minutes) and then either fractalkine or fractalkine + candesartan 8 (10 minutes) using concentrations outlined in the main text. -

Supplementary Materials Functional Characterization of Rare RAB12

1 Supplementary materials Functional characterization of rare RAB12 variants and their role in musician’s and other dystonias Eva Hebert et al. Figure S1. Photograph of Individual L-10289 (mildly affected mother of the index patient from Family D) showing a 15-degree tilt of the trunk to the right as well as dystonic posturing of the right hand (involuntary flexion of the third to fifth finger and thumb and extension of the index finger). 2 Figure S2. TFRC colocalized with wildtype and mutant FLAG-RAB12. Immunofluorescent staining of fibroblasts expressing FLAG-RAB12 WT, p.Gly13Asp, or p.Ile196Val revealed predominant perinuclear localization of TFRC (red) which overlaps with the localization of FLAG-RAB12 (green) in all three cell lines (WT, p.Gly13Asp, p.Ile196Val). The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 20µm. 3 Figure S3. Lysosomal degradation of the physiological dimeric TFRC was not affected by the RAB12 mutations. Western Blot analysis revealed the degradation of TFRC in patient fibroblasts with endogenous expression of RAB12 (a, b) in fibroblasts ectopically expressing FLAG-RAB12 (c, d), and in SH-SY5Y cells ectopically expressing FLAG-RAB12 (e, f). Cells were treated with Bafilomycin A1 for 24h. ß-actin served as loading control and for normalization. Bars in B, D, and F indicate means of three independent experiments ± SEM. ctrl control, WT wildtype 4 Figure S4. Relative LC3-II protein levels are marginally increased in SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing RAB12 Gly13Asp protein and p62 levels remained constant. a) Western Blot of proteins extracted from stably transfected SH-SY5Y cells. Expression of FLAG-tagged RAB12 WT equals the expression of mutated RAB12 proteins (Gly13Asp, I196Val) (lane 3, 5, 7). -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Panoply™ Human NPR3 Over-Expressing Stable Cell Line

Panoply™ Human NPR3 Over-expressing Stable Cell Line HEK293-NPR3 Lot. No. (See product label) CELL LINE INFORMATION Cat.No. CSC-SC010567 Cell Line Description HEK293-NPR3 cell line is clonally derived from HEK293 cell line, which has been transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding: 1) full length human NPR3 under the CMV promoter, and 2) puromycin resistance gene under the control of PGK promoter. Overexpression of human NPR3 has been quantified by qPCR. Background NPR3 (natriuretic peptide receptor 3) is an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor that in humans is encoded by the NPR3 gene. This protein is one of three natriuretic peptide receptors. It is responsible for clearing circulating and extracellular natriuretic peptides through endocytosis of the receptor. Natriutetic peptides are small peptides which regulate blood volume and pressure, pulmonary hypertension, and cardiac function as well as some metabolic and growth processes. Host Cell HEK293 Gene Information Gene Name Natriuretic peptide receptor 3 Official Symbol NPR3 Species Homo sapiens (human) GeneID 4883 mRNA Reference NM_000908.3 Protein Reference NP_000899.1 Synonyms NPRC; ANP-C; ANPRC; NPR-C; ANPR-C; GUCY2B; C5orf23 SAFETY AND PACKAGING Mycoplasma Mycoplasma Status: Negative (MycoAlert Kit) Format One frozen vial Storage Liquid nitrogen Safety Considerations The following safety precautions should be observed. 1. Use pipette aids to prevent ingestion and keep aerosols down to a minimum. 2. No eating, drinking or smoking while handling the stable line. 3. Wash hands after handling the stable line and before leaving the lab. 4. Decontaminate work surface with disinfectant or 70% ethanol before and after working with stable cells. -

Gene Pval Qval Log2 Fold Change AAMP 0.895690332 0.952598834

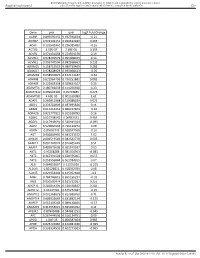

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut Gene pval qval Log2 Fold Change AAMP 0.895690332 0.952598834 -0.21 ABI3BP 0.002302151 0.020612283 0.465 ACHE 0.103542461 0.296385483 -0.16 ACTG2 2.99E-07 7.68E-05 3.195 ACVR1 0.071431098 0.224504378 0.19 ACVR1C 0.978209579 0.995008423 0.14 ACVRL1 0.006747504 0.042938663 0.235 ADAM15 0.158715519 0.380719469 0.285 ADAM17 0.978208929 0.995008423 -0.05 ADAM28 0.038932876 0.152174187 -0.62 ADAM8 0.622964796 0.790251882 0.085 ADAM9 0.122003358 0.329623107 0.25 ADAMTS1 0.180766659 0.414256926 0.23 ADAMTS12 0.009902195 0.05703885 0.425 ADAMTS8 4.60E-05 0.001169089 1.61 ADAP1 0.269811968 0.519388039 0.075 ADD1 0.233702809 0.487695826 0.11 ADM2 0.012213453 0.066227879 -0.36 ADRA2B 0.822777921 0.915518785 0.16 AEBP1 0.010738542 0.06035531 0.465 AGGF1 0.117946691 0.320915024 -0.095 AGR2 0.529860903 0.736120272 0.08 AGRN 0.85693743 0.928047568 -0.16 AGT 0.006849995 0.043233572 1.02 AHNAK 0.006519543 0.042542779 0.605 AKAP12 0.001747074 0.016405449 0.51 AKAP2 0.409929603 0.665919397 0.05 AKT1 0.95208288 0.985354963 -0.085 AKT2 0.367391504 0.620376005 0.055 AKT3 0.253556844 0.501934205 0.07 ALB 0.064833867 0.21195036 -0.315 ALDOA 0.83128831 0.918352939 0.08 ALOX5 0.029954404 0.125352668 -0.3 AMH 0.784746815 0.895196237 -0.03 ANG 0.050500474 0.181732067 0.255 ANGPT1 0.281853305 0.538528647 0.285 ANGPT2 0.43147281 0.675272487 -0.15 ANGPTL2 0.001368876 0.013688762 0.71 ANGPTL4 0.686032669 0.831882134 -0.175 ANPEP 0.019103243 0.089148466 -0.57 ANXA2P2 0.412553021 0.665966092 0.11 AP1M2 0.87843088 0.944681253 -0.045 APC 0.267444505 0.516134751 0.09 APOD 1.04E-05 0.000587404 0.985 APOE 0.023722987 0.104981036 -0.395 APOH 0.336334555 0.602273505 -0.065 Sundar R, et al. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Growth and Molecular Profile of Lung Cancer Cells Expressing Ectopic LKB1: Down-Regulation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Phosphate Kinase/PTEN Pathway1

[CANCER RESEARCH 63, 1382–1388, March 15, 2003] Growth and Molecular Profile of Lung Cancer Cells Expressing Ectopic LKB1: Down-Regulation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Phosphate Kinase/PTEN Pathway1 Ana I. Jimenez, Paloma Fernandez, Orlando Dominguez, Ana Dopazo, and Montserrat Sanchez-Cespedes2 Molecular Pathology Program [A. I. J., P. F., M. S-C.], Genomics Unit [O. D.], and Microarray Analysis Unit [A. D.], Spanish National Cancer Center, 28029 Madrid, Spain ABSTRACT the cell cycle in G1 (8, 9). However, the intrinsic mechanism by which LKB1 activity is regulated in cells and how it leads to the suppression Germ-line mutations in LKB1 gene cause the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome of cell growth is still unknown. It has been proposed that growth (PJS), a genetic disease with increased risk of malignancies. Recently, suppression by LKB1 is mediated through p21 in a p53-dependent LKB1-inactivating mutations have been identified in one-third of sporadic lung adenocarcinomas, indicating that LKB1 gene inactivation is critical in mechanism (7). In addition, it has been observed that LKB1 binds to tumors other than those of the PJS syndrome. However, the in vivo brahma-related gene 1 protein (BRG1) and this interaction is required substrates of LKB1 and its role in cancer development have not been for BRG1-induced growth arrest (10). Similar to what happens in the completely elucidated. Here we show that overexpression of wild-type PJS, Lkb1 heterozygous knockout mice show gastrointestinal hamar- LKB1 protein in A549 lung adenocarcinomas cells leads to cell-growth tomatous polyposis and frequent hepatocellular carcinomas (11, 12). suppression. To examine changes in gene expression profiles subsequent to Interestingly, the hamartomas, but not the malignant tumors, arising in exogenous wild-type LKB1 in A549 cells, we used cDNA microarrays.