When We Say US TM , We Mean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Media Business Models: Lessons from the Video Game Sector

Komorowski, M and Delaere, S. (2016). Online Media Business Models: Lessons from the Video Game Sector. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 11(1), 103–123, DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.16997/wpcc.220 RESEARCH ARTICLE Online Media Business Models: Lessons from the Video Game Sector Marlen Komorowski and Simon Delaere imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit, Brussels, BE Corresponding author: Marlen Komorowski ([email protected]) Today’s media industry is characterized by disruptive changes and business models have been acknowledged as a driving force for success. Current business model research manages only to grasp static descriptions while in reality media managers are struggling with the dynamics of the industry. This article aims to close this gap by investigating a new paradigm of online media business models. Based on three video game case studies of the massively multiplayer online role-playing game genre, this article explores a novel theoretical approach to explain the changes that can be made within business models. The article highlights the importance of changing processes within online media business models and emphasises that the video game sector is at the forefront of business innovation. Finally, it demonstrates that online media business model change is in a trade-off paradigm between capturing or offering potentially higher value per player vs. accessing a potentially larger player-base. Key words: Media industry; business model; process; disruption; video game sector Introduction Today’s media industry is characterized by disruptive transformations shaped by digitization. Digitization is not only generating new business opportunities but threatens traditional commercialization strategies and is proving highly unpredictable with regards to future market development. -

Section One: Getting Started

Section One: Getting Started As you get started on your journey, you will be faced with a few decisions. Some of these will have minimal impact on your long term play, while others will play an important part in how you experience the game. This section will cover the first of those decisions – server (known as ‘shards’ in UO) selection, character creation, and an explanation of the different clients used to play the game (Classic and Enhanced). In this section we will also cover some of the most basic elements of the game that will be a foundation for understanding your new world. This will include basic movement controls, as well as how to use the overhead radar feature. Choose Your Client – Classic vs. Enhanced We will begin with an explanation of the two clients available for use with Ultima Online – the Classic Client and the Enhanced Client. Your choice of client will greatly affect how you view, and play, the game. The best part about having two different clients is that you are not bound to one or another – you are free to switch back and forth so long as you have both installed on your system. Following is a brief explanation of the differences between the two clients. Later in this section will be pictures illustrating some of the differences between the two clients. Classic Client The Classic Client is the original client used to play Ultima Online. It does not have as many features as the Enhanced Client, but is still preferred by many longtime players who favor its simpler nature and the nostalgia that comes with experiencing the game as it was originally intended. -

Gaming Habits and Self-Determination: Conscious and Non-Conscious Paths to Behavior Continuance

GAMING HABITS AND SELF-DETERMINATION: CONSCIOUS AND NON-CONSCIOUS PATHS TO BEHAVIOR CONTINUANCE By Donghee Yvette Wohn A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Media and Information Studies – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT GAMING HABITS AND SELF-DETERMINATION: CONSCIOUS AND NON-CONSCIOUS PATHS TO BEHAVIOR CONTINUANCE By Donghee Yvette Wohn This dissertation examines how non-conscious habits and conscious motivations contribute to an individual’s intention to continue playing online multiplayer games. It empirically examines distinct predictions of behavioral intention based on different theories in two gaming contexts—casual social network games (SNGs) and massively multiplayer online games (MMOs). Addressing inconsistencies in prior studies, habit is conceptualized as the mental construct of automaticity, thus distinguishing habit from frequency of past behavior and self-identity. Results indicate that strong habits positively predict behavior continuation intention and moderate the effect of motivation for SNGs but not MMOs. Self-identity was a positive predictor for both genres. Gender differences in self-determined motivation were present in social network games but not massively multiplayer online games. The residual effect of past behavior was stronger than any conscious or non-conscious processes; once perceived frequency of past behavior was taken into consideration, it was the strongest indicator of behavioral continuation intentions. Copyright by DONGHEE YVETTE WOHN 2013 Dedicated to my progressive grandparents, who believed that higher education was the most important indicator of success for a woman. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my dear advisor, Robert LaRose, whose sharp critiques have prepared me for the most ferocious of peer reviewers; whose brilliant insights bore holes in dams of existing scholarship, making way for innovative paradigms; and whose sincere love for students represents the pinnacle of the true spirit of higher education. -

Player, Pirate Or Conducer? a Consideration of the Rights of Online Gamers

ARTICLE PLAYER,PIRATE OR CONDUCER? A CONSIDERATION OF THE RIGHTS OF ONLINE GAMERS MIA GARLICK I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................. 423 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................. 426 A. KEY FEATURES OF ONLINE GAMES ............................ 427 B. AGAMER’S RIGHT OF OUT-OF-GAME TRADING?......... 428 C. AGAMER’S RIGHT OF IN-GAME TECHNICAL ADVANCEMENT?......................................................... 431 D. A GAMER’S RIGHTS OF CREATIVE GAME-RELATED EXPRESSION? ............................................................ 434 III. AN INITIAL REVIEW OF LIKELY LEGAL RIGHTS IN ONLINE GAMES............................................................................ 435 A. WHO OWNS THE GAME? .............................................. 436 B. DO GAMERS HAVE RIGHTS TO IN-GAME ELEMENTS? .... 442 C. DO GAMERS CREATE DERIVATIVE WORKS?................ 444 1. SALE OF IN-GAME ITEMS - TOO COMMERCIAL? ...... 449 2. USE OF ‘CHEATS’MAY NOT INFRINGE. .................. 450 3. CREATIVE FAN EXPRESSION –ASPECTRUM OF INFRINGEMENT LIKELIHOOD?.............................. 452 IV. THE CHALLENGES GAMER RIGHTS POSE. ....................... 454 A. THE PROBLEM OF THE ORIGINAL AUTHOR. ................ 455 B. THE DERIVATIVE WORKS PARADOX............................ 458 C. THE PROBLEM OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICATION OF COPYRIGHTED MATERIALS. ....................................... 461 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................. 462 © 2005 YALE -

![[Thesis Title Goes Here]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7295/thesis-title-goes-here-747295.webp)

[Thesis Title Goes Here]

REAL ECONOMICS IN VIRTUAL WORLDS: A MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME CASE STUDY, RUNESCAPE A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Tanla E. Bilir In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Digital Media in the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Georgia Institute of Technology December 2009 COPYRIGHT BY TANLA E. BILIR REAL ECONOMICS IN VIRTUAL WORLDS: A MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME CASE STUDY, RUNESCAPE Approved by: Dr. Celia Pearce, Advisor Dr. Kenneth Knoespel School of Literature, Communication, and School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Culture Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Rebecca Burnett Dr. Ellen Yi-Luen Do School of Literature, Communication, and College of Architecture & College of Culture Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: July 14, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been a wonderful journey. I consider myself lucky finding an opportunity to combine my background in economics with my passion for gaming. This work would not have been possible without the following individuals. First of all, I would like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Celia Pearce, Dr. Rebecca Burnett, Dr. Kenneth Knoespel, and Dr. Ellen Yi-Luen Do for their supervision and invaluable comments. Dr. Pearce has been an inspiration to me with her successful work in virtual worlds and multiplayer games. During my thesis progress, she always helped me with prompt feedbacks and practical solutions. I am also proud of being a member of her Mermaids research team for two years. I am deeply grateful to Dr. Knoespel for supporting me through my entire program of study. -

Module 2 Roleplaying Games

Module 3 Media Perspectives through Computer Games Staffan Björk Module 3 Learning Objectives ■ Describe digital and electronic games using academic game terms ■ Analyze how games are defined by technological affordances and constraints ■ Make use of and combine theoretical concepts of time, space, genre, aesthetics, fiction and gender Focuses for Module 3 ■ Computer Games ■ Affect on gameplay and experience due to the medium used to mediate the game ■ Noticeable things not focused upon ■ Boundaries of games ■ Other uses of games and gameplay ■ Experimental game genres First: schedule change ■ Lecture moved from Monday to Friday ■ Since literature is presented in it Literature ■ Arsenault, Dominic and Audrey Larochelle. From Euclidian Space to Albertian Gaze: Traditions of Visual Representation in Games Beyond the Surface. Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies. 2014. http://www.digra.org/digital- library/publications/from-euclidean-space-to-albertian-gaze-traditions-of-visual- representation-in-games-beyond-the-surface/ ■ Gazzard, Alison. Unlocking the Gameworld: The Rewards of Space and Time in Videogames. Game Studies, Volume 11 Issue 1 2011. http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/gazzard_alison ■ Linderoth, J. (2012). The Effort of Being in a Fictional World: Upkeyings and Laminated Frames in MMORPGs. Symbolic Interaction, 35(4), 474-492. ■ MacCallum-Stewart, Esther. “Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives. Game Studies, Volume 14 Issue 2 2014. http://gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart ■ Nitsche, M. (2008). Combining Interaction and Narrative, chapter 5 in Video Game Spaces : Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds, MIT Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://chalmers.instructure.com/files/738674 ■ Vella, Daniel. Modelling the Semiotic Structure of Game Characters. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Game Developer Magazine

>> INSIDE: 2007 AUSTIN GDC SHOW PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 2007 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SAVE EARLY, SAVE OFTEN >>THE WILL TO FIGHT >>EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW MAKING SAVE SYSTEMS FOR CHANGING GAME STATES HARVEY SMITH ON PLAYERS, NOT DESIGNERS IN PANDEMIC’S SABOTEUR POLITICS IN GAMES POSTMORTEM: PUZZLEINFINITE INTERACTIVE’S QUEST DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 11, 2007 Using Autodeskodesk® HumanIK® middle-middle- Autodesk® ware, Ubisoftoft MotionBuilder™ grounded ththee software enabled assassin inn his In Assassin’s Creed, th the assassin to 12 centuryy boots Ubisoft used and his run-time-time ® ® fl uidly jump Autodesk 3ds Max environment.nt. software to create from rooftops to a hero character so cobblestone real you can almost streets with ease. feel the coarseness of his tunic. HOW UBISOFT GAVE AN ASSASSIN HIS SOUL. autodesk.com/Games IImmagge cocouru tteesyy of Ubiisofft Autodesk, MotionBuilder, HumanIK and 3ds Max are registered trademarks of Autodesk, Inc., in the USA and/or other countries. All other brand names, product names, or trademarks belong to their respective holders. © 2007 Autodesk, Inc. All rights reserved. []CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2007 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 FEATURES 7 SAVING THE DAY: SAVE SYSTEMS IN GAMES Games are designed by designers, naturally, but they’re not designed for designers. Save systems that intentionally limit the pick up and drop enjoyment of a game unnecessarily mar the player’s experience. This case study of save systems sheds some light on what could be done better. By David Sirlin 13 SABOTEUR: THE WILL TO FIGHT 7 Pandemic’s upcoming title SABOTEUR uses dynamic color changes—from vibrant and full, to black and white film noir—to indicate the state of allied resistance in-game. -

EA Games Frank Gibeau, President

EA Games Frank Gibeau, President 1 Safe Harbor Statement Some statements set forth in this presentation, including estimates and targets relating to future financial results (e.g., revenue, profitability, margins), operating plans, business strategies, objectives for future operations, and industry growth rates contain forward-looking statements that are subject to change. Statements including words such as "anticipate", "believe", “estimate”, "expect" or “target” and statements in the future tense are forward- looking statements. These forward-looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties that could cause actual events or actual future results to differ materially from the expectations set forth in the forward-looking statements. Some of the factors which could cause the Company’s results to differ materially from its expectations include the following: timely development and release of Electronic Arts’ products; competition in the interactive entertainment industry; the Company’s ability to successfully implement its Label structure and related reorganization plans; the consumer demand for, and the availability of an adequate supply of console hardware units (including the Xbox 360, the PLAYSTATION3, and the Wii); consumer demand for software for legacy consoles, particularly the PlayStation 2; the Company’s ability to predict consumer preferences among competing hardware platforms; the Company’s ability to realize the anticipated benefits of its acquisition of VG Holding Corp. and other acquisitions and strategic transactions -

Lo Spazio Ionico E La Comunità Della Grecia Occidentale: Territorio

Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichità e del Vicino Oriente PRIN 2007 La ‘terza’ Grecia e l’Occidente Convegno Lo spazio ionico e le comunità della Grecia nord-occidentale Territorio, società, istituzioni a cura di Claudia Antonetti Venezia, 7-9 gennaio 2010 Si ringrazia Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini di Venezia Sede del convegno Venezia, Università Caʹ Foscari Palazzo Marcorà Malcanton, Sala Conferenze Dorsoduro 3484/D 30123 Venezia Segreteria dott. Damiana Baldassarra, dott. Edoardo Cavalli Laboratorio di Epigrafia greca Dipartimento di Scienze dellʹAntichità e del Vicino Oriente Palazzo Marcorà Malcanton ‐Dorsoduro 3484/D ‐30123 Venezia tel. +39 041 234 6361 fax +39 041 234 6370 e‐mail: [email protected] 2 PRESENTAZIONE Con questo convegno si desidera instaurare un dialogo tra storici ed archeologi che studiano la Grecia nord‐occidentale per favorire la discussione e la comunicazione di informazioni scientifiche. Le linee guida che strutturano l’incontro sono l’interconnessione fra la Grecia nord‐occidentale e le Isole ioniche, le analogie e i contatti con l’Occidente, la possibile esistenza di una koinè interregionale nell’ambito della storia materiale, sociale, istituzionale che esiga la costituzione di un autonomo campo di ricerca e ne motivi la funzionalità. Il convegno si situa all’interno delle attività del Progetto di rilevante interesse nazionale (PRIN) 2007 La ‘terza’ Grecia e l’Occidente (http://www.storia.unina.it/grecia/) ed è organizzato da Claudia Antonetti, responsabile scientifico dell’Unità di ricerca di Ca’ Foscari, con l’aiuto dei suoi colleghi e collaboratori: Stefania De Vido, Damiana Baldassarra, Edoardo Cavalli, Francesca Crema, Silvia Palazzo, Ivan Matijašić, Anna Ruggeri. -

Massive Multi-Player Online Games and the Developing Political Economy of Cyberspace

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 4 • Issue 1 • 2008 doi:10.32855/fcapital.200801.010 Massive Multi-player Online Games and the Developing Political Economy of Cyberspace Mike Kent This article explores economics, production and wealth in massive multi-player online games. It examines how the unique text of each of these virtual worlds is the product of collaboration between the designers of the worlds and the players who participate in them. It then turns its focus to how this collaborative construction creates tension when the ownership of virtual property is contested, as these seemingly contained virtual economies interface with the global economy. While these debates occur at the core of this virtual economy, at the periphery cheap labor from less-developed economies in the analogue world are being employed to ‘play’ these games in order to ‘mine’ virtual goods for resale to players from more wealthy countries. The efforts of the owners of these games, to curtail this extra-world trading, may have inadvertently driven the further development of this industry towards larger organizations rather than small traders, further cementing this new division of labor. Background In the late 1980s, multi-user dungeons (MUDs) such as LambdaMOO were text-based environments. These computer-mediated online spaces drew considerable academic interest.[1] The more recent online interactive worlds are considerably more complex, thanks to advances in computing power and bandwidth. Encompassing larger and more detailed worlds, they also enclose a much larger population of players. The first game in the new category of Massively Multi-player Online Role-playing Games (known initially by the acronym MMORPG and more recently as MMOG) was Ultima Online http://www.uo.com, which was launched over a decade ago in September 1997. -

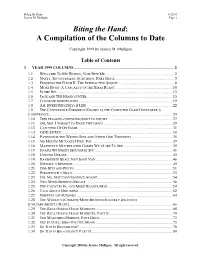

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29