The Lost World of the Administrative Procedure Act: a Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book

LOST WORLD: ENGLAND 1933-1936 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy Hartley,Lucy Worsley,Adrian Bailey | 272 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | PROSPECT BOOKS | 9781903018972 | English | Blackawton, United Kingdom Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book Brian Stableford makes a related point about Lost Worlds: "The motif has gradually fallen into disuse by virtue of increasing geographical knowledge; these days lost lands have to be very well hidden indeed or displaced beyond some kind of magical or dimensional boundary. Smoo Cave 7. Mat Johnson 's Pym describes giant white hominids living in ice caves. Contemporary American novelist Michael Crichton invokes this tradition in his novel Congo , which involves a quest for King Solomon's mines, fabled to be in a lost African city called Zinj. Much of the material first appeared in her weekly columns for the Daily Sketch from to and 65 of these, together with some of the author's evocative photos, have been collected in this book. Most popular. Rhubarbaria : Recipes for Rhubarb. EAN: Caspak in the Southern Ocean. Topics Paperbacks. Cancel Delete comment. Crusoe Warburton , by Victor Wallace Germains , describes an island in the far South Atlantic, with a lost, pre-gunpowder empire. New England Paperback Books. Here the protagonists encounter an unknown Inca kingdom in the Andes. New other. Updating cart She describes meeting an old woman in sand dunes by the sea, cutting marram grass, "gray as dreams and strong as a promise given". Create a commenting name to join the debate Submit. She was also a teacher herself and wrote much journalism, principally on country matters. -

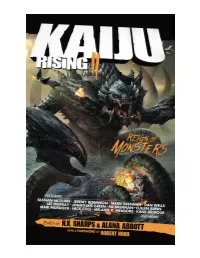

Kaiju-Rising-II-Reign-Of-Monsters Preview.Pdf

KAIJU RISING II: Reign of Monsters Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix “Te Ghost in the Machine” © 2018 Jonathan Green “Winter Moon and the Sun Bringer” © 2018 Kane Gilmour “Rancho Nido” © 2018 Guadalupe Garcia McCall “Te Dive” © 2018 Mari Murdock “What Everyone Knows” © 2018 Seanan McGuire “Te Kaiju Counters” © 2018 ML Brennan “Formula 287-f” © 2018 Dan Wells “Titans and Heroes” © 2018 Nick Cole “Te Hunt, Concluded” © 2018 Cullen Bunn “Te Devil in the Details” © 2018 Sabrina Vourvoulias “Morituri” © 2018 Melanie R. Meadors “Maui’s Hook” © 2018 Lee Murray “Soledad” © 2018 Steve Diamond “When a Kaiju Falls in Love” © 2018 Zin E. Rocklyn “ROGUE 57: Home Sweet Home” © 2018 Jeremy Robinson “Te Genius Prize” © 2018 Marie Brennan Te characters and events portrayed in this book are fctitious or fctitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specifed. Tis book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 Paperback: 978-1-947659-30-8 EPUB: 978-1-947659-31-5 MOBI: 978-1-947659-32-2 PDF-Merchant: 978-1-947659-33-9 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: N.X. Sharps & Alana Abbott Cover Illustration: Tan Ho Sim Interior Illustrations: Frankie B. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

Mythopoeia, Colonialism and Redress in the Morobe Goldfields in Papua New Guinea

GOLD, TADPOLES AND JESUS IN THE MANGER: MYTHOPOEIA, COLONIALISM AND REDRESS IN THE MOROBE GOLDFIELDS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA DANIELE MORETTI In 1936 Beatrice Blackwood became the first ethnographer to work with the Anga people of Papua New Guinea (PNG).1 In her own words, her aim was to learn “what [she] could of the life of a modern Stone Age people..., for in this way an ethnologist can sometimes fill up some of the gaps in the archaeological record” (Blackwood 1939: 11). Of course, this attempt at anthropological time travel (Fabian 1983) was only made possible by the “pacification” of a small number of Upper Watut villages following the discovery of gold in the neighbouring Wau-Bulolo Valley and Mount Kaindi over the previous decade. For the Anga of the Bulolo District, the opening of the Morobe Goldfields in the 1920s marked the beginning of a new colonial epoch. Beyond that, the event encouraged prospectors and administration to push inland in search of similar strikes, thus promoting the spread of colonial power, not just to the core of Anga country but also to the wider Highlands region. Between the 1920s and PNG national independence in 1975 the Morobe Goldfields produced great mineral riches that transformed the townships of Wau and Bulolo into booming industrial enclaves and sustained colonial expansion throughout the Mandated Territory of New Guinea (a political unit subsequently united with Papua under colonial rule). Yet little of this wealth was spent for the benefit of the Upper Watut or of the Anga more generally. What is more, just as independence approached and growing numbers of Anga became involved in the Goldfields’ economy, the Bulolo District’s large-scale mining industry ground to a halt and local employment opportunities and services declined significantly. -

The Lost World Points for Understanding Answer

ELEMENTARY LEVEL ■ The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Points for Understanding 1 6 1 He was a reporter for a newspaper in London. The news- 1 Gomez and Miguel had pushed the tree into the abyss. paper is called the ‘Daily Gazette’. 2 Professor Challenger They had done it because Gomez hated Roxton. Roxton had said that he had found some wonderful animals in South killed Pedro Lopez. He was Gomez’ brother. 2 They asked America. Many people didn’t believe him. Malone went to see him to stay in the camp at the bottom of the rock. They Professor Challenger. He wanted to find out if Challenger was asked him to send one of the Indians to get some long ropes. telling the truth. 3 He had a very large head with a red face And they asked him to tell the Indian to send Malone’s report and grey eyes. He had a long black beard. His hands were big, to Mr McArdle in London. 3 A huge animal. Professor strong and covered with thick black hair. 4 Malone asked Challenger said that he thought a dinosaur had made them. Challenger some questions. But they were not very good 4 He was looking into a pit where hundreds of pterodactyls questions. Challenger soon knew that Malone was not a sci- were sitting. 5 Something had broken things in the camp. It ence student. Challenger guessed that he was a reporter. He had taken the food from some of their tins. tried to throw him out of the house. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

This Character Is Portrayed As Unfeminine and “Married” to Their Work. They Can Be Transformed by a Love Interest, but Reinf

Andra Campbell This is Dr. Flicker! We’re going to use her paper “Between Hey everyone! My names Andra and I want Brains and Breasts-Women Scientists in Fiction Film: On the to tell you about the Marginalization and Sexualization of Scientific Competence” to ways that women in look at ways women in STEM in media have been portrayed by looking at the common-stereotypes throughout films . STEM have been represented in media! Hi everyone, I’m Dr. Flicker! Stereotype 1… This character is portrayed as unfeminine and “married” to their work. They can be transformed by a love interest, but reinforce the stereotype that feminine women can’t be intelligent. Check out Dr. Peterson from the movie Spellbound (1945), or Amy Fowler from the Big Bang Theory (2007) for an example! Stereotype 2… This portrays a woman who must be “one of the guys” in order to prove herself. She is sometimes inferior to her male counterparts. An example is Dr. Leavitt from The Andromeda Strain (1971) or Dr. Augustine from Avatar (2009). This portrayal reinforces the negative stereotype that science is for “The Andromeda Strain (1971).” IMDb, www.imdb.com/ men. Stereotype 3… Dr. Sarah Harding from The Lost World: Jurassic Park This character has little (1997) is an example of significance towards The Naive Expert you may the scientific theme of recognize! the movie, is feminine, and often a love interest. Her naïveté often gets her in trouble, with a man “The Lost World: Jurassic Park (Universal, 1997).” Heritage rescuing her. Auctions, 2 Sept. 2018, movieposters.ha.com/itm/ movie-posters/science-fiction/the-lost-world- jurassic-park-universal-1997-lenticular-one- sheet-27-x-41-science-fiction/a/161835-51233.s. -

Remixing Generalized Symbolic Media in the New Scientific Novel Søren Brier

Ficta: remixing generalized symbolic media in the new scientific novel Søren Brier To cite this version: Søren Brier. Ficta: remixing generalized symbolic media in the new scientific novel. Public Un- derstanding of Science, SAGE Publications, 2006, 15 (2), pp.153-174. 10.1177/0963662506059441. hal-00571086 HAL Id: hal-00571086 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00571086 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SAGE PUBLICATIONS (www.sagepublications.com) PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF SCIENCE Public Understand. Sci. 15 (2006) 153–174 Ficta: remixing generalized symbolic media in the new scientific novel1 Søren Brier This article analyzes the use of fictionalization in popular science commu- nication as an answer to changing demands for science communication in the mass media. It concludes that a new genre—Ficta—arose especially with the work of Michael Crichton. The Ficta novel is a fiction novel based on a real scientific problem, often one that can have or already does have serious consequences for our culture or civilization. The Ficta novel is a new way for the entertainment society to reflect on scientific theories, their consequences and meaning. -

History, in Celluloid Joanne Bernardi Introduces Students to the Delicate Art of Preserving Films—And to the Enduring Appeal of “Monster/Creature” Movies

In RevIew FIlm StudIeS History, in Celluloid Joanne Bernardi introduces students to the delicate art of preserving films—and to the enduring appeal of “monster/creature” movies. By Kathleen McGarvey There are many iconic images of the nuclear age, but among those spawned by pop culture, perhaps none is more famil- iar than a certain enormous lizard. Atomic Creatures: Godzilla, a film and media stud- ies course taught this fall by Joanne Bernar- di, an associate professor of Japanese and a MONSTER KING: Bernardi (with her own collection of monster movie memorabilia) teaches member of the film and media studies pro- a course on Japanese monster films, a genre that has established Godzilla (above) as a gram faculty, takes a look at the phenom- fixture in global popular culture since the postnuclear lizard’s debut in 1954. 12 ROCHESTER REVIEW November–December 2010 Getty ImaGes (GoDzIlla); aDam FeNster (BerNarDI) 3_RochRev_Nov10_Review.indd 12 10/29/10 11:16 AM In RevIew enon that generated and helped define the doctorate in Japanese and film studies at the diversity of national film industries, Japanese kaiju eiga, or monster film. Columbia before she ever encountered the and helps students become more aware of “I think it’s the most important course I original Gojira. It played at the Public The- the breadth of film and media studies as a teach—it’s a matter of life and death,” says ater’s Summer in Japan film series in New discipline. It also gives us an appreciation Bernardi, who says the films bring together York City in 1982. -

FIRESIDE BOOKS HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE 2019 a Selection of Recent Favorites Picked by Your Local Booksellers

FIRESIDE BOOKS HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE 2019 A selection of recent favorites picked by your local booksellers The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa The government systematically makes ordinary things “disappear,” perfume, calendars, roses, birds, photographs … and your associated memories. But some people remember. —Mary Ann Steller’s Orchid by Thomas McGuire A young botanist finds himself in over his head on a quest to the Shumagin Islands in 1924 following rumors of an orchid last seen by naturalist Georg Steller. A wonderfully atmospheric glimpse into an old Alaska of fish traps, wooden boats, and inscrutable smugglers on wild islands. —Ruth Wanderers by Chuck Wendig A plague of sleepwalkers: unresponsive, unstoppable, explosive when forcibly halted. Incredibly compelling, stay-up-way-past-bedtime, twisty and timely and scary! A deeply satisfying read. —Kate Refugium: Poems for the Pacific (edited by Yvonne Blomer) Ranging from playful to mournful, you can practically smell the saltwater when you read this stunning collection of poems about the Pacific. —Jessica Belzebubs by JP Ahonen A collection of short mockumentary comics about everyday family struggles–when the family happens to be a black metal band. —Justice Rotherweird by Andrew Caldecott No local history or anything before 1800 may be taught in this mysterious town. Join a delightful cast of strange but likeable characters to find out why! —Nathan Nothing to See Here by Kevin Wilson In this wonderfully bizarre novel, a woman is tasked with being the caretaker to two children who spontaneously combust into flames when agitated. Strange, funny, and profoundly affecting, Wilson writes with a breezy style which, despite its premise, always remains grounded and tells a uniquely human story of the complicated mess that is parenting. -

Rhetorics of the Fantastic: Re-Examining Fantasy As Action, Object, and Experience

Rhetorics of the Fantastic: Re-Examining Fantasy as Action, Object, and Experience Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Rick, David Wesley Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 15:03:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631281 RHETORICS OF THE FANTASTIC: RE-EXAMINING FANTASY AS ACTION, OBJECT, AND EXPERIENCE by David W. Rick __________________________ Copyright © David W. Rick 2019 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 Rick 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: David W. Rick Rick 4 Acknowledgments Since I began my program at the University of Arizona, I have been supported in innumerable ways by many dedicated people. Dr. Ken McAllister has been a mentor beyond all my expectations and has offered, in addition to advising, no end of encouragement and inspiration. -

Lost Races, Which in Turn Are Often Utopian Fictions

1 About Catalogue VIII We visited with George Locke recently, who’s doing well, and picked up six boxes of Lost Race novels. The following catalogue, our ninth, is the result. We’ve taken a little time out to read a chapter here and there of some of the stories herein. Some are pretty good, some are quite poor. Either way, they deserve to be remembered. Many of the titles herewith are genuinely rare. We’ve located copies of all of them somewhere, mostly in libraries. Many are in Blieler’s Checklist, nearly all are in Locke’s Spectrum, as they should be as George’s collection is where most of the copies have been plucked from. John Clute and John Grants’ Encyclopaedia has been essential too in the cataloguing, as has Lloyd Currey’s extensive stock. George collected these over several decades, and it would be an injustice to not commemorate that in some way. The very fact that each title has included a brief synopsis is testament to the import of George’s contribution to the genre. There are 28 items in this catalogue, all revolving around Lost Races, which in turn are often utopian fictions. Supplementary to these items are a few dozen books grouped into one lot primarily for ease of cataloguing and value. They would make an excellent starter for a collector with an interest in the area. The Lost Race subgenre has certainly tailed off over the last few decades. Greater exploration beyond and within earth’s bounds, satellite mapping and easier communication has meant that the notion of finding a lost race on or within earth is less plausible and stories therefore become more twee.