Literary Modes of Representation in Dino Buzzati's Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book

LOST WORLD: ENGLAND 1933-1936 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy Hartley,Lucy Worsley,Adrian Bailey | 272 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | PROSPECT BOOKS | 9781903018972 | English | Blackawton, United Kingdom Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book Brian Stableford makes a related point about Lost Worlds: "The motif has gradually fallen into disuse by virtue of increasing geographical knowledge; these days lost lands have to be very well hidden indeed or displaced beyond some kind of magical or dimensional boundary. Smoo Cave 7. Mat Johnson 's Pym describes giant white hominids living in ice caves. Contemporary American novelist Michael Crichton invokes this tradition in his novel Congo , which involves a quest for King Solomon's mines, fabled to be in a lost African city called Zinj. Much of the material first appeared in her weekly columns for the Daily Sketch from to and 65 of these, together with some of the author's evocative photos, have been collected in this book. Most popular. Rhubarbaria : Recipes for Rhubarb. EAN: Caspak in the Southern Ocean. Topics Paperbacks. Cancel Delete comment. Crusoe Warburton , by Victor Wallace Germains , describes an island in the far South Atlantic, with a lost, pre-gunpowder empire. New England Paperback Books. Here the protagonists encounter an unknown Inca kingdom in the Andes. New other. Updating cart She describes meeting an old woman in sand dunes by the sea, cutting marram grass, "gray as dreams and strong as a promise given". Create a commenting name to join the debate Submit. She was also a teacher herself and wrote much journalism, principally on country matters. -

Normality Fantasy Fantastic Storytelling, Rhymes, Songs; Exploring Italian Through Literature, Poetry and Music

Normality Fantasy Fantastic Storytelling, rhymes, songs; exploring Italian through literature, poetry and music. By Andrea Francesco Manno • Introduction to Dino Buzzati • Dino Buzzati is an Italian writer, painter, artist and journalist who lived in northern Italy during the 1900s. He is one of the most important Italian authors of the 20th century • His worldwide fame is mostly due to his novel ”The Tartar Step”, although he is also known for his collections of short stories. • His ”Sessanta racconti”, a short-story collection that won the Strega Prize in 1958, features elements of science fiction, fantasy and horror. • Buzzati’s words about normality, style and fantastic: • […] It seems to me that fantasy should be as close as possible to journalism.[…] • The effectiveness of a fantastic story will depend on its being told in the most simple and practical terms.[…] • Una goccia d’acqua sale per i gradini della scala. La senti? Disteso in letto nel buio , ascolto il suo arcano cammino” […]. Dino Buzzati. Una goccia. “ Sessanta Racconti”. • https://www.dariopalma.com/images/Buzzati_Le_S Story telling and torie_Dipinte_3.JPG?378 painting: • https://www.dariopalma.com/images/Buzzati_Le_S torie_Dipinte_4.JPG?378 “Le storie dipinte”. • https://www.exibart.com/repository/media/eventi /2005/05/dino-buzzati-8211-storie-disegnate-e- An art graphic dipinte.jpg novel in which ordinary life meets the fantastic. Introduction to Gianni Rodari. • Rodari is considered Italy's most important 20th- The grammar of century children's author and his books have been translated into many languages. His approach to fantasy in “ Il libro writing and story telling is playful and aims to stimulate the imagination and fantasy. -

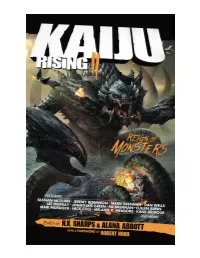

Kaiju-Rising-II-Reign-Of-Monsters Preview.Pdf

KAIJU RISING II: Reign of Monsters Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix “Te Ghost in the Machine” © 2018 Jonathan Green “Winter Moon and the Sun Bringer” © 2018 Kane Gilmour “Rancho Nido” © 2018 Guadalupe Garcia McCall “Te Dive” © 2018 Mari Murdock “What Everyone Knows” © 2018 Seanan McGuire “Te Kaiju Counters” © 2018 ML Brennan “Formula 287-f” © 2018 Dan Wells “Titans and Heroes” © 2018 Nick Cole “Te Hunt, Concluded” © 2018 Cullen Bunn “Te Devil in the Details” © 2018 Sabrina Vourvoulias “Morituri” © 2018 Melanie R. Meadors “Maui’s Hook” © 2018 Lee Murray “Soledad” © 2018 Steve Diamond “When a Kaiju Falls in Love” © 2018 Zin E. Rocklyn “ROGUE 57: Home Sweet Home” © 2018 Jeremy Robinson “Te Genius Prize” © 2018 Marie Brennan Te characters and events portrayed in this book are fctitious or fctitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specifed. Tis book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 Paperback: 978-1-947659-30-8 EPUB: 978-1-947659-31-5 MOBI: 978-1-947659-32-2 PDF-Merchant: 978-1-947659-33-9 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: N.X. Sharps & Alana Abbott Cover Illustration: Tan Ho Sim Interior Illustrations: Frankie B. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

Biografia Di Alberto Moravia

NonSoloBiografie - Tutte le biografie nel web... NonSoloBiografie: Alberto Moravia Alberto Moravia (per l'anagrafe Alberto Pincherle: il cognome Moravia è quello della nonna paterna) nasce il 28 novembre 1907 a Roma, in via Sgambati, da un'agiata famiglia borghese. Il padre, Carlo Pincherle Moravia, architetto e pittore, è di origine veneziana, mentre la madre, Gina de Marsanich, è di Ancona. Terzo di quattro figli (Adriana, Elena e Gastone, nato nel 1914), Alberto ha una «prima infanzia normale benché solitaria». All'età di nove anni si verifica «il fatto più importante della sua vita», quello che l'autore stesso riteneva avesse inciso «sulla sua sensibilità in maniera determinante»: la malattia da cui non guarirà del tutto che verso i diciassette anni, lasciandolo leggermente claudicante. All'età di nove anni, infatti, Alberto si ammala di tubercolosi ossea, malattia dagli atroci dolori che lo costringe a letto per cinque anni: i primi tre a casa, e gli ultimi due nel sanatorio Codivilla di Cortina d'Ampezzo. Durante questo periodo i suoi studi (interrotti alla licenza ginnasiale, suo unico titolo di studio) sono irregolari. Tuttavia, legge innumerevoli libri, soprattutto i classici e i massimi narratori dell'Ottocento e del primo Novecento (Dostoevskij, Joyce, Goldoni, Shakespeare, Molière, Mallarmé, Leopardi e molti altri); scrive versi in francese e in italiano, e studia tedesco. Dopo aver lasciato il sanatorio nell'autunno del 1925, durante la convalescenza a Bressanone, in provincia di Bolzano, dà inizio alla stesura de Gli indifferenti, che verrà pubblicato con gran successo nel 1929. La sua salute rimane fragile ed è costretto a vivere in alberghi di montagna passando da un luogo all'altro. -

The Case of Alberto Carocci (1926-1939)

Habitus and embeddedness in the Florentine literary field: the case of Alberto Carocci (1926-1939) Article Accepted Version La Penna, D. (2018) Habitus and embeddedness in the Florentine literary field: the case of Alberto Carocci (1926- 1939). Italian Studies, 73 (2). pp. 126-141. ISSN 1748-6181 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00751634.2018.1444536 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/75567/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00751634.2018.1444536 Publisher: Taylor and Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Habitus and Embeddedness in the Florentine Literary Field: The Case of Alberto Carocci (1926-1939) Daniela La Penna Department of Modern Languages and European Studies, University of Reading, Reading, UK [email protected] 1 Habitus and Embeddedness in the Florentine Literary Field: The Case of Alberto Carocci (1926-1939) This article intends to show how the notion of embeddedness, a concept derived from network theory, can improve our understanding of how a journal’s reliance on regional and national intellectual networks impacts the journal’s performance. The study takes as test case Alberto Carocci’s editorship of Solaria. -

Descrizione Centro Manoscritti

Il Fondo Ferrieri presso il Centro Manoscritti dell’Università di Pavia Nicoletta Trotta Il Fondo Ferrieri è stato acquisito dal Centro di ricerca sulla tradizione manoscrit- ta di autori moderni e contemporanei dell’Università di Pavia nel 1991 per volontà dei figli di Enzo Ferrieri: in una lettera del 12 settembre 1991Anna Ferrieri Castelli e Giuliano Ferrieri scrivevano al Magnifico Rettore dell’ateneo pavese per confer- mare la donazione di «tutto il materiale autografo inedito conservato da Enzo Fer- rieri, che testimonia l’intenso scambio di corrispondenza, di idee e di iniziative culturali» che il loro «padre ebbe con i protagonisti della vita intellettuale italiana ed europea durante il ventennio tra le due guerre» e promettevano di consegnare,a completamento del materiale già affidato, i numeri disponibili della rivista «Il Convegno». Qualche mese prima il Centro Manoscritti aveva dedicato a questa importante acquisizione una mostra documentaria dal titolo “Il Convegno”di Enzo Ferrieri e la cultura europea dal 1920 al 1940, tenutasi a Pavia, presso la Sala dell’Annunciata, dall’11 al 25 maggio.Il ricco catalogo,1 curatodaAngeloStella,siapreconlacorpo- sa sezione Le sale della letteratura italiana diAnna Modena,seguono i contributi di Guido Lopez, Eugenio Levi, la“coscienza inquieta” del“Convegno”, di Maria Fancel- li,2 Oltre Chiasso e diAndrea Mancini, I segni della regia: la voce,l’albero,la bottiglia rovesciata;chiude il volume lo spoglio della rivista, “Il Convegno”: indice degli auto- ri e delle opere recensite,perlecuredichiscrive. -

Mythopoeia, Colonialism and Redress in the Morobe Goldfields in Papua New Guinea

GOLD, TADPOLES AND JESUS IN THE MANGER: MYTHOPOEIA, COLONIALISM AND REDRESS IN THE MOROBE GOLDFIELDS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA DANIELE MORETTI In 1936 Beatrice Blackwood became the first ethnographer to work with the Anga people of Papua New Guinea (PNG).1 In her own words, her aim was to learn “what [she] could of the life of a modern Stone Age people..., for in this way an ethnologist can sometimes fill up some of the gaps in the archaeological record” (Blackwood 1939: 11). Of course, this attempt at anthropological time travel (Fabian 1983) was only made possible by the “pacification” of a small number of Upper Watut villages following the discovery of gold in the neighbouring Wau-Bulolo Valley and Mount Kaindi over the previous decade. For the Anga of the Bulolo District, the opening of the Morobe Goldfields in the 1920s marked the beginning of a new colonial epoch. Beyond that, the event encouraged prospectors and administration to push inland in search of similar strikes, thus promoting the spread of colonial power, not just to the core of Anga country but also to the wider Highlands region. Between the 1920s and PNG national independence in 1975 the Morobe Goldfields produced great mineral riches that transformed the townships of Wau and Bulolo into booming industrial enclaves and sustained colonial expansion throughout the Mandated Territory of New Guinea (a political unit subsequently united with Papua under colonial rule). Yet little of this wealth was spent for the benefit of the Upper Watut or of the Anga more generally. What is more, just as independence approached and growing numbers of Anga became involved in the Goldfields’ economy, the Bulolo District’s large-scale mining industry ground to a halt and local employment opportunities and services declined significantly. -

The Lost World Points for Understanding Answer

ELEMENTARY LEVEL ■ The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Points for Understanding 1 6 1 He was a reporter for a newspaper in London. The news- 1 Gomez and Miguel had pushed the tree into the abyss. paper is called the ‘Daily Gazette’. 2 Professor Challenger They had done it because Gomez hated Roxton. Roxton had said that he had found some wonderful animals in South killed Pedro Lopez. He was Gomez’ brother. 2 They asked America. Many people didn’t believe him. Malone went to see him to stay in the camp at the bottom of the rock. They Professor Challenger. He wanted to find out if Challenger was asked him to send one of the Indians to get some long ropes. telling the truth. 3 He had a very large head with a red face And they asked him to tell the Indian to send Malone’s report and grey eyes. He had a long black beard. His hands were big, to Mr McArdle in London. 3 A huge animal. Professor strong and covered with thick black hair. 4 Malone asked Challenger said that he thought a dinosaur had made them. Challenger some questions. But they were not very good 4 He was looking into a pit where hundreds of pterodactyls questions. Challenger soon knew that Malone was not a sci- were sitting. 5 Something had broken things in the camp. It ence student. Challenger guessed that he was a reporter. He had taken the food from some of their tins. tried to throw him out of the house. -

Dino Buzzati Published on Iitaly.Org (

Honoring a 20th Century Renaissance Man: Dino Buzzati Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Honoring a 20th Century Renaissance Man: Dino Buzzati Natasha Lardera (October 30, 2012) Kairos Italy Theater, Casa Italiana's theater company in residence, and a leading group in the making of bilingual theater in New York City, has undergone the mission to bring Dino Buzzati's work to the United States. It organized a successful evening of literature, theater and cinema @ Casa and introduced theater performances to be held at the Cherry Lane Theater next week (weather permitting). “Each one of us has a favorite Buzzati: the author of The Tartar Steppe, the artist and illustrator or the journalist of Il Corriere della Sera.” With these words Stefano Albertini, Director of NYU's Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò introduced an exciting evening of literature, theater and cinema to mark the 40th anniversary of the death of Dino Buzzati, a real Renaissance Man from the 20th century. The evening was designed by Kairos Italy Theater, Casa Italiana's theater company in residence, a leading group in the making of bilingual theater in New York City. Its founder and creative director, Laura Caparrotti, used Albertini's words to further explain the Renaissance man concept, explaining Page 1 of 3 Honoring a 20th Century Renaissance Man: Dino Buzzati Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) that Buzzati was a writer whose work was mandatory in high school so kids read his work unwillingly without really appreciating it. Those same kids discovered him later in life when no one was forcing them to read his stuff. -

Translating Buzzati

Translating Buzzati: Domesticating and Foreignising Strategies By Niall Harland Duncan A thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Literary Translation Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2011 Abstract Methodologies within Modern Translation Studies are often broadly defined by two seemingly polarised ideologies: foreignisation and domestication. Current theory tends to favour foreignising translations which has led to a marginalisation of domestication as a viable and valid approach. This thesis is an examination of domestication as a still-legitimate approach in the field of translation. The project consists of original translations of four short stories by noted Italian author Dino Buzzati, which together with commentaries provide a practical platform on which to analyse the characteristics and advantages of the approach. Additionally, building on these examples is a more general discussion of these two approaches, an examination of their respective strengths and weaknesses and an evaluation of domestication as a methodology that can still offer advantages in effective translation. 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to the Italian Programme of The Victoria University of Wellington which I have greatly enjoyed being part of for the past five years. Special thanks to Dr Claudia Bernardi for her assistance as supervisor for the beginning of this project; and to Dr Marco Sonzogni for his much appreciated guidance, support and friendship. Many thanks to Jimmy, my family and friends for their invaluable love, support and feedback. Finally, I would like to thank Dino Buzzati for writing the excellent stories that provided the basis of project: grazie mille.