Commentary the Poetic C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book

LOST WORLD: ENGLAND 1933-1936 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy Hartley,Lucy Worsley,Adrian Bailey | 272 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | PROSPECT BOOKS | 9781903018972 | English | Blackawton, United Kingdom Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book Brian Stableford makes a related point about Lost Worlds: "The motif has gradually fallen into disuse by virtue of increasing geographical knowledge; these days lost lands have to be very well hidden indeed or displaced beyond some kind of magical or dimensional boundary. Smoo Cave 7. Mat Johnson 's Pym describes giant white hominids living in ice caves. Contemporary American novelist Michael Crichton invokes this tradition in his novel Congo , which involves a quest for King Solomon's mines, fabled to be in a lost African city called Zinj. Much of the material first appeared in her weekly columns for the Daily Sketch from to and 65 of these, together with some of the author's evocative photos, have been collected in this book. Most popular. Rhubarbaria : Recipes for Rhubarb. EAN: Caspak in the Southern Ocean. Topics Paperbacks. Cancel Delete comment. Crusoe Warburton , by Victor Wallace Germains , describes an island in the far South Atlantic, with a lost, pre-gunpowder empire. New England Paperback Books. Here the protagonists encounter an unknown Inca kingdom in the Andes. New other. Updating cart She describes meeting an old woman in sand dunes by the sea, cutting marram grass, "gray as dreams and strong as a promise given". Create a commenting name to join the debate Submit. She was also a teacher herself and wrote much journalism, principally on country matters. -

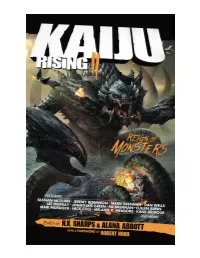

Kaiju-Rising-II-Reign-Of-Monsters Preview.Pdf

KAIJU RISING II: Reign of Monsters Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix “Te Ghost in the Machine” © 2018 Jonathan Green “Winter Moon and the Sun Bringer” © 2018 Kane Gilmour “Rancho Nido” © 2018 Guadalupe Garcia McCall “Te Dive” © 2018 Mari Murdock “What Everyone Knows” © 2018 Seanan McGuire “Te Kaiju Counters” © 2018 ML Brennan “Formula 287-f” © 2018 Dan Wells “Titans and Heroes” © 2018 Nick Cole “Te Hunt, Concluded” © 2018 Cullen Bunn “Te Devil in the Details” © 2018 Sabrina Vourvoulias “Morituri” © 2018 Melanie R. Meadors “Maui’s Hook” © 2018 Lee Murray “Soledad” © 2018 Steve Diamond “When a Kaiju Falls in Love” © 2018 Zin E. Rocklyn “ROGUE 57: Home Sweet Home” © 2018 Jeremy Robinson “Te Genius Prize” © 2018 Marie Brennan Te characters and events portrayed in this book are fctitious or fctitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specifed. Tis book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 Paperback: 978-1-947659-30-8 EPUB: 978-1-947659-31-5 MOBI: 978-1-947659-32-2 PDF-Merchant: 978-1-947659-33-9 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: N.X. Sharps & Alana Abbott Cover Illustration: Tan Ho Sim Interior Illustrations: Frankie B. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

SHADOWLANDS Introduction

SHADOWLANDS Introduction ‘Shadowlands’ tells of the extraordinary love between C. S. Lewis, the famous writer and Christian academic and Joy Gresham, an American poet who came to know him first through his writing. She was to die shortly after their marriage. ‘Shadowlands’ was first a television and then a stage play and is now a film starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. This guide is for use before and after a viewing of Richard Attenborough’s film. It seeks to expand for class work the themes of love and bereavement, the risks of emotional involvement and the challenge to all faiths of pain and tragedy as well as discussing the way film tackles these difficult subjects. JACK AND JOY Olive Staples Lewis - known always as Jack - was born in 1898 in Belfast three years after the Lewis’s first son, Warren or “Warnie”. The brothers were very close, and spent much of their adult bachelor life living together near Oxford in a ramshackle house, The Kilns, known to their friends as The Midden (Old English for dung heap). What impressions do we first receive of the brothers? How does the film express briefly a little of their life “before” Joy? What do we learn during the course of the film of C. S. Lewis’s world? Apart from Joy, what other women do we “meet” in ‘Shadowlands’? How are they represented? Find out a little about Britain in the 1950s. Who was Prime Minister? When did rationing end? Why was Princess Margaret known as the “heartbreak princess”? As well as picture and library research, ask those who were alive at the time. -

Mythopoeia, Colonialism and Redress in the Morobe Goldfields in Papua New Guinea

GOLD, TADPOLES AND JESUS IN THE MANGER: MYTHOPOEIA, COLONIALISM AND REDRESS IN THE MOROBE GOLDFIELDS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA DANIELE MORETTI In 1936 Beatrice Blackwood became the first ethnographer to work with the Anga people of Papua New Guinea (PNG).1 In her own words, her aim was to learn “what [she] could of the life of a modern Stone Age people..., for in this way an ethnologist can sometimes fill up some of the gaps in the archaeological record” (Blackwood 1939: 11). Of course, this attempt at anthropological time travel (Fabian 1983) was only made possible by the “pacification” of a small number of Upper Watut villages following the discovery of gold in the neighbouring Wau-Bulolo Valley and Mount Kaindi over the previous decade. For the Anga of the Bulolo District, the opening of the Morobe Goldfields in the 1920s marked the beginning of a new colonial epoch. Beyond that, the event encouraged prospectors and administration to push inland in search of similar strikes, thus promoting the spread of colonial power, not just to the core of Anga country but also to the wider Highlands region. Between the 1920s and PNG national independence in 1975 the Morobe Goldfields produced great mineral riches that transformed the townships of Wau and Bulolo into booming industrial enclaves and sustained colonial expansion throughout the Mandated Territory of New Guinea (a political unit subsequently united with Papua under colonial rule). Yet little of this wealth was spent for the benefit of the Upper Watut or of the Anga more generally. What is more, just as independence approached and growing numbers of Anga became involved in the Goldfields’ economy, the Bulolo District’s large-scale mining industry ground to a halt and local employment opportunities and services declined significantly. -

The Lost World Points for Understanding Answer

ELEMENTARY LEVEL ■ The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Points for Understanding 1 6 1 He was a reporter for a newspaper in London. The news- 1 Gomez and Miguel had pushed the tree into the abyss. paper is called the ‘Daily Gazette’. 2 Professor Challenger They had done it because Gomez hated Roxton. Roxton had said that he had found some wonderful animals in South killed Pedro Lopez. He was Gomez’ brother. 2 They asked America. Many people didn’t believe him. Malone went to see him to stay in the camp at the bottom of the rock. They Professor Challenger. He wanted to find out if Challenger was asked him to send one of the Indians to get some long ropes. telling the truth. 3 He had a very large head with a red face And they asked him to tell the Indian to send Malone’s report and grey eyes. He had a long black beard. His hands were big, to Mr McArdle in London. 3 A huge animal. Professor strong and covered with thick black hair. 4 Malone asked Challenger said that he thought a dinosaur had made them. Challenger some questions. But they were not very good 4 He was looking into a pit where hundreds of pterodactyls questions. Challenger soon knew that Malone was not a sci- were sitting. 5 Something had broken things in the camp. It ence student. Challenger guessed that he was a reporter. He had taken the food from some of their tins. tried to throw him out of the house. -

A CS Lewis Related Cumulative Index of <I>Mythlore</I>

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 10 1998 A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84 Glen GoodKnight Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation GoodKnight, Glen (1998) "A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Author and subject index to articles, reviews, and letters in Mythlore 1–84. Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Bibliography; Mythlore—Indexes This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 MYTHLORE I s s u e 8 4 Sum m er 1998 P a g e 5 9 A C.S. -

Willow Creek: the Fiction of C

C.S. Lewis and the Apologetics of Story Some have claimed that C.S. Lewis drifted towards fiction the last decade of his life because he was failed as an Apologist and no longer able to keep up with the complex philosophical questions of his day. In fact, fiction was always part of Lewis’s output. He wrote, “The imaginative man in me is older than the rational man and more continually operative.” Lewis used story as one of the tools in his rhetorical tool box because he knew that some people will not listen to a coherent and reasonable presentation of the Gospel. Their rejection of the things of God is buttressed with rationalization and self-justification. Reason stands before these people’s hearts like dragon sentries preventing even the best apologetic arguments from getting through. But, Lewis believed, sometimes story can get past watchful dragons. This Network will explore Lewis’s use of story as a rhetorical and apologetical tool for the Gospel. Jerry Root is Professor of Christian Education at Wheaton College and serves as the Director of the Evangelism Initiative. Jerry is a graduate of Whittier College and Talbot Graduate School of Theology at Biola University; he received his PhD from the Open University. Jerry is the author or co-author of numerous books on C.S. Lewis, including The Surprising Imagination of C.S. Lewis: An Introduction, with Mark Neal, C.S. Lewis and a Problem of Evil: An Investigation of a Pervasive Theme, and The Soul of C.S. Lewis: A Meditative Journey through Twenty-six of His Best Loved Writings. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

The Hansen Lectureship Series from Intervarsity Press

Splendour in the Dark C. S. Lewis’s Dymer in His Life and Work November 3, 2020 | $20, 256 pages, paperback | 978-0-8308-5375-5 Several years before he converted to Christianity, C. S. Lewis published a narrative poem, Dymer, which not only sheds light on the development of his literary skills but also offers a glimpse of his intellectual and spiritual growth. Including the complete annotated text of Lewis’s poem, this volume helps us understand both Lewis’s change of mind and our own journeys of faith. The Hansen Lectureship Series from InterVarsity Press The Hansen Lectureship Series features reflections related to the imaginative work and lasting influence of seven British authors, including C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, George MacDonald, and Dorothy L. Sayers. The books in the series are based on the Ken and Jean Hansen Lectureship, an annual lecture series hosted at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College, named in honor of former Wheaton College trustee Ken Hansen and his wife, Jean, and endowed in their memory by Walter and Darlene Hansen. Each book includes three lectures by a Wheaton College faculty member on one or more of the Wade Center authors with responses by fellow faculty members. Founded in 1965, the Marion E. Wade Center houses a major research collection of writings and related materials by and about seven British authors: Owen Barfield, G. K. Chesterton, C. S. Lewis, George MacDonald, Dorothy L. Sayers, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams. The Wade Center collects, preserves, and makes these resources available to researchers and visitors through its reading room, museum displays, educational programming, and publications. -

V the POSTHUMOUS NARRATIVE POEMS OF

'/v$A THE POSTHUMOUS NARRATIVE POEMS OF C. S. LEWIS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Caroline L. Geer, B. A. Denton, Texas December, 1976 Geer, Caroline Lilian, The Posthumous Narrative Poems of C. S. Lewis. Master of Arts (English), December, 1976, 73 pp., bibliography, 15 titles. The purpose of this study is to introduce the three posthumous narrative poems of C. S. Lewis. Chapter One is an introduction to Lewis's life and scholarship. The second chapter is concerned with "Launceloti" in which the central theme of the story explores the effect of the Quest for the Holy Grail on King Arthur's kingdom. Chapter Three studies "The Nameless Isle," in which Celtic and Greek mythic ele- ments strongly influence both characterization and plot. The fourth chapter is an analysis of The Queen of Drum and its triangular plot structure in which the motivating impetus of the characters is the result of dreams. Chapter Five recapitulates Lewis1s perspectives of life and reviews the impact of his Christianity on the poems. The study also shows how each poem illustrates a separate aspect of the cosmic quest. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION. 1 II. "LAUNCELOT . 13 III. "THE NAMELESS ISLE" . 32 IV. THE QUEEN OF DRUM: A STORY jflFIVECANTOS ......... 50 V. CONCLUSION . * . 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 72 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nothing about a literature can be more essential than the language it uses. A language has its own personality; implies an outlook, reveals a mental activity, and has a resonance, not quite the same as those of any other. -

Course Syllabus

The Life and Thought of C.S. LEWIS TH 2XL3 / MS 2XL3 McMaster Divinity College Summer School, 2015 Instructors: Bradley K. Broadhead, Ph.D. (Cand.) [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION C.S. Lewis is one the most influential Christian writers of the twentieth century. Just over fifty years after his death, his theological writings and works of fiction (which are often one and the same) remain widely read and appreciated. The story of his life demonstrates in a powerful way how his encounter with Jesus Christ definitively shaped both his worldview and his actions. Together we will walk through his life and his major writings, considering his relevance for the contemporary world. COURSE OBJECTIVES Knowing To become familiar with the life and major works of Lewis To identify the major themes that emerge from Lewis’ corpus To understand the arguments for the value of contemporary parables/myths Being To engage in theological reflection on the works of Lewis To be challenged by the example of Lewis in leading a Christian life Doing To critically engage with a selected portion of Lewis’ work To evaluate Lewis’ impact on Christian and secular cultures SPECIALIZATIONS Christian Thought and History Church and Culture Christian Worldview 2 1 CLASS SCHEDULE Week 1 Tuesday, May 26 Introduction to the Course Young Lewis Lewis the Academic Lewis at War Thursday, May 28 Lewis the Atheist Lewis’ Conversion Lewis and the Inklings Week 2 Tuesday, June 2 Lewis the Popular Christian Apologist Mere Christianity The Problem of Pain Miracles Thursday, June 4 Lewis the Writer The Space Trilogy The Screwtape Letters The Great Divorce Week 3 Tuesday, June 9 The Chronicles of Narnia Until We Have Faces Thursday, June 11 Lewis, Joy, and A Grief Observed Lewis and Evangelicalism Lewis and contemporary issues 1 Please note that the instructor reserves the right to make alterations to the content and its sequence.