On Better Judo Moti Nativ – 2017 Better Judo Is a Series of 5 Articles, Published from January 1948 Until January 1949, Which Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mikonosuke Kawaishi - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 1

Mikonosuke Kawaishi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 1 Mikonosuke Kawaishi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Mikonosuke (Mikinosuke) Kawaishi ( Kawaishi Mikonosuke, born 1899 - 1969) was a master of Japanese Judo and Jujutsu, reaching for the life of the 7th Dan, who led the development of Judo in France and much of Europe. The application of belt colors associated with different degrees of learning resulted in a very effective teaching approach for the development of martial arts that was later used in most of the world and other martial arts and sports. By the Fédération Française posthumous judo and jiu-jitsu gives him the 10th Dan. Biography Kawaishi born in Kyoto in 1899 and having studied Judo and Jujutsu at the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (Greater Japan Association of Martial Virtue). He left Japan in the mid-1920s to travel and see the world and began by touring the United States of America, teaching jujitsu particularly in New York and San Diego. By 1928 he had arrived in the United Kingdom and soon established a school in Liverpool and with his close friend Gunji Koizumi (nearly 10 years his senior) was now well established in the UK having formed the London Budokwai Club and a school at the famous Oxford University. In 1931, he moved to London where he founded the Anglo-Japanese Judo Club and also began teaching Judo at Oxford University with Kouzumi. With the Asian martial arts still relatively new to England, he was forced to supplement his meagre earnings as a teacher by becoming a professional wrestler. -

Dan – Prüfungsordnung Mai 2011

Begleitmaterial zum Dan-Prüfungsprogramm Ein Nachschlagewerk zu verschiedenen Themen der Dan-Prüfungsordnung im Deutschen Judo Bund e.V. Dan – Prüfungsordnung Mai 2011 Impressum: 4. überarbeitete Auflage Autoren: Hannes Daxbacher, Klaus Hanelt, Roman Jäger, Klaus Keßler, Ulrich Klocke, Ralf Lippmann, Rudi Mieth, Dr. paed. habil. Hans Müller-Deck, Jan Schröder, Mario Staller, Dr. Hans-Jürgen Ulbricht, Franz Zeiser Redaktion: Ralf Lippmann, Roman Jäger, Dr. Robert Neumann, Boris Teofanovic im Auftrag des Deutschen Judo Bundes e.V. © Copyright 2011 2 Vorwort Liebe Judoka, nachdem wir 2004 das neue Kyu-Programm gemeinsam verabschiedet haben und dieses mittlerweile mit großer Anerkennung in allen Landesverbänden angenommen wurde, war die logische Konsequenz die Erstellung eines darauf aufbauenden passenden Dan-Programms. Dieses Programm liegt nun vor und ich möchte mich ausdrücklich bei allen Mitarbeitern, die sowohl haupt- als auch überwiegend ehrenamtlich an der Erstellung beteiligt waren, be- danken. Unser gesamtes Ausbildungs- und Prüfungssystem, vom Elementarbereich und dem Kyu- Programm, über die Rahmentrainingskonzeption bis hin zur Traineraus- und Fortbildung findet nicht nur im Deutschen Olympischen Sportbund, sondern auch über die Grenzen hinweg mittlerweile auch international große Anerkennung und hat im deutschsprachigen Raum eine gewisse Vorbildfunktion. Das neue Dan-Ausbildungs- und Prüfungsprogramm soll unser System vervollständigen und abrunden. Ich wünsche auch dieser „Dan-Prüfungsordnung“ eine hohe Akzeptanz im Sinne unser aller gemeinsamen Ziele, der Weiterentwicklung der Sportart Judo in Deutschland. Peter Frese Präsident des Deutschen Judo Bundes e.V. 3 Inhalt Seite 1. Einleitung 05 2. Grundlagen des Dan-Prüfungsprogramms 06 2.1 Orientierung und Zielsetzung 06 2.2 Leitideen 06 2.2.1 Ausbildungsstufen 07 2.3 Der schwarze Gürtel in der Öffentlichkeit 07 2.4 Technikauswahl / Nomenklatur 08 3. -

The History of Judo, Part 4

Jigoro Kano, The Founding, History & Evolution Of Judo By Phil Morris Part 4 Kodokan Judo’s Founding And International Growth Again the Kodokan moved premises from Kano’s 20 mat house, and formed at the residence of Yajiro Shinagawa, an ambassador of the new Meiji Period, in Fujimi- cho, Tokyo. Shinagawa was a very broad minded man and very generous, as well as being a student of Judo. This new dojo held an area of 40 mats. It was from this Dojo, that for the next 3 years Judo excelled over all other rival Jujutsu school in contests. 1887 saw the categorisation of Judo complete. The Kodokan had three broad aims: physical education, contest proficiency and mental training. Its structure as a martial art was such that it could be practiced as a competitive sport. Blows, kicks, certain joint locks, and other techniques too dangerous for competition, were taught only to the higher ranks. “Atemi” or striking techniques were not fully eliminated from Judo per se except in competition, but were retained in the practice of Kata, taught at the time only to higher graded students. These “Atemi” techniques are still to be found today in Judo’s Kata. To accommodate yet again the ever increasing numbers of Judo students, the Kodokan moved to the Hongo-ku in Masaga-cho, Tokyo which could hold 60 mats in 1890. By now Kano’s vision of Judo becoming a world sport had started and he took his first trip abroad to Europe and the US to give lectures and teach Judo in 1889. -

Livret Des Grades Et De Culture Judo-Jujitsu

Judo LIVRET DES GRADES ET DE CULTURE JUDO-JUJITSU VERSION 9.0 Jujitsu PRESENTATION Le Judo, la plus belle invention du Japon. Au Japon, une légende dit que les principes du Judo furent découverts par un moine, lors d'un terrible hiver en observant les branches d'arbres chargées de neige. Les plus grosses cassaient sous le poids, les plus souples pliaient et se débarrassaient de l'agresseur naturel. Ce qu'il avait découvert du comportement des branches pouvait peut-être servir aux hommes... C'est en observant les techniques de Jujitsu, que les samouraïs utilisaient dans leur lutte pour la survie, que Jigoro Kano, universitaire de haut rang, fin lettré et maître en arts martiaux, révélait en 1882 cet art un peu mystérieux : le Judo, littéralement "voie de la souplesse". Ce véritable art de vivre aux valeurs pédagogiques, mélange typique d'exercices physiques et spirituels, propose à l'individu un ensemble de règles de conduite propice à l'épanouissement. Loin des préceptes figés et des commandements rigides, le judoka apprend à contrôler son corps et à se maîtriser. Jigoro Kano supprime les coups frappés des anciennes techniques de combat pour ne retenir que projections et contrôles. Il impose la saisie du Judogi. Son objectif est alors de développer un système sportif et éducatif sans aucun danger pour les pratiquants. L'Histoire est désormais en marche et le Judo connaît un essor fantastique, bien au-delà de son Japon natal. Il est aujourd'hui en France le 3ème sport le plus pratiqué, avec plus d'un demi- million de licenciés à la Fédération Française de Judo. -

Book: Martial Arts After 40-Proper Form% Moves

BOOK: MARTIALH eAllo.R SiTgnS in oAr reFgiTsteEr R H4e0lp -&P CoRntOactPER FORM% MOVES EXERCISES FOR OLDER PEOPLE, KARATE Sell My eBay Shop by Advanced category Search for anything All Categories Search Back to home page | Listed in category: Books, Comics & Magazines > Non-Fiction This listing has ended. BOOK:MARTIAL ARTS AFTER 40-PROPER FORM%MOVES Shop with confidence EXERCISES FOR OLDER PEOPLE,KARATE eBay Money Back Guarantee Condition: Good Get the item you ordered or your money back. Learn more “Good Condition” US $9.99 Seller information Approximately EUR 8.45 telemosaic (3094 ) 100% Positive Feedback Save this seller See other items No additional import charges on delivery. Visit Shop This item will be sent through the Global Shipping Programme and includes Click to view larger image and other views international tracking. Learn more Postage: US $19.83 (approx. EUR 16.78) International Priority Shipping to Canada | See details Item location: Canton, Massachusetts, United States Posts to: United States and many other countries | See details Import US $0.00 (amount confirmed at checkout) Have one to sell? Sell it yourself charges: Delivery: Estimated within 8-14 working days Includes international tracking Payments: International postage and import charges paid to Pitney Bowes Inc. Learn More Returns: No returns accepted | See details Report item Description Postage and payments eBay item number: 233230621981 Seller assumes all responsibility for this listing. Last updated on 05 Feb, 2020 02:53:58 GMT View all revisions Item specifics Condition: Good : Seller notes: “Good Condition” Format: Paperback Topic: Martial Arts Publication Year: 1999 Author: Sang H. -

On Better Judo

21 On Better Judo Moti Nativ Better Judo is a series of five articles Dr. Feldenkrais wrote for the Quarterly Bulletin of the Judo Budokwai Club in London between January 1948 and January 1949. 1 Adin Steinsaltz, The Thirteen Petalled Rose: A “A true secret is still a secret even when it is revealed to all.”1 Discourse on the Essence of Jewish Existence (New York: Basic Books, 2006), Judo concepts and techniques had a significant impact on trans. from the Hebrew Dr. Feldenkrais’ development of the Feldenkrais Method® of somatic edition. education. We can see the results in many Awareness Through 2 Moshe Feldenkrais, Movement® (ATM®) lessons, although the judo component may not A.B.C. du JUDO (Paris: E. Chiron, 1938), Higher Judo: always be obvious to those without the proper background. In my Groundwork (Berkeley, CA: research on Moshe during the years 1920–1950, I did a detailed study Blue Snake Books, 2010), 2, 3 JUDO–the Art of Defense of his judo and self-defense books. As a martial artist, my study was and Attack (London & New not just theoretical. It involved experiencing the techniques myself and York: Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd., 1953). teaching them to others. Through this study of Moshe’s work, I came to better understand his way of thinking about self-preservation and how 3 Moshe Feldenkrais, this relates to the Feldenkrais Method in general. Jiu-Jitsu and Self-Defense (1930), Practical Unarmed Recently, with the help of Dr. Mike Callan, I managed to obtain a Combat (London & New series of five articles, entitled Better Judo, which Feldenkrais wrote for York: Frederick Warne & Co. -

Kōdōkan Jūdō's Three Orphaned Forms of Counter Techniques

REVIEW ARTICLE Kōdōkan Jūdō’s Three Orphaned Forms of Counter Techniques – Part 1: The Gonosen-no-kata – “Forms of Post-Attack Initiative Counter Throws” Carl De CréeABDE Authors’ Contribution: Department of Languages and Cultures, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, Ghent University, Belgium A Study Design B Data Collection Source of support: private resources C Statistical Analysis D Manuscript Preparation E Funds Collection Received: 30 October 2014; Accepted: 26 March 2015; Published online: 23 April 2015 ICID: 1151330 Abstract Background & Study Aim. The purpose of the present paper is to provide a comprehensive study ofgonosen-no-kata [“Forms of Post- Attack Initiative Counter Throws”], a non-officially accepted kata of Kōdōkan jūdō made popular in Western Europe by Kawaishi Mikinosuke (1899-1969). Material & Methods. To achieve this we apply historical methods and source criticism to offer a careful critical analysis of the ori- gin, history and background of this kata. Results. The first verifiable appearance of gonosen-no-kata is in 1926 at the occasion of the London Budōkwai’s 9th Annual Display, where it was publicly demonstrated by Ishiguro Keishichi (1897-1974), previously at Waseda University and since 1924 living in Paris. Thekata builds on intellectual material conceived by Takahashi Kazuyoshi. A 1932 program brochure of an Oxford University Judo Club event is the oldest known source to link Kawaishi and gonosen-no-kata. Kawaishi considered gonosen-no-kata as the third randori-no-kata. Kawaishi’s major role in spreading jūdō in France and continental Europe between 1935 and 1965, and the publication of his seminal jūdō kata book in 1956, connected his name to this kata forever. -

The 10Th Lecture Kosei Inoue

The 10th Lecture Solidarity of International Judo Education The 10th Lecture Subsequently, with the cooperation of many people, we invited junior high school students from Israel Kosei Inoue and Palestine to Japan, where we held an exchange program through judo for about two weeks. In this “Reports on His Two-year Training lecture, first I would like to talk about the details of in the United Kingdom” the program. Next, Mr. Toshiaki Hashimoto, our Assistant Executive Director, will report on the Sunday, June 5, 2011 workshop and lecture held at the second Lecture Hall, Annex, International House of Japan Japan-China Judo Friendship Center opened on March 1 last year in Nanjing, China. Finally, Mr. Opening Address and Report on the Judo Inoue will deliver his lecture. Exchange Program with Palestinian Children To begin with, let me show you some footage Yasuhiro Yamashita broadcast by NHK showing the Israeli and Palestinian children we invited in December last In my capacity as Executive Director of the NPO year. Please also refer to the hand-out article Solidarity of International Judo Education, I would regarding our exchange programs with Israel and like to thank you all very much for coming to our Palestine, if you have time. (Video shown.) 10th Lecture Meeting, despite your busy schedules. Here, I should make a correction. It was our NPO, This lecture meeting will feature a report from Mr. Solidarity of International Judo Education, not Kosei Inoue, the former Olympic Champion and my myself, that invited these children. Please excuse pupil, who has returned to Japan after completing a me for failing to provide this most important two-year training course in Europe. -

Culture Judo Et Conférences

Le Judo s’exporte vers l’occident Kano entreprit ses premiers voyages autour du monde et fit pénétrer le Judo en Europe et en Amérique par des démonstrations Culture Judo et conférences. Il confia à ses meilleurs élèves la direction du kodokan. Le maître Kano présenta, en 1889, une première Petit Samouraï raconte, démonstration de judo à Marseille. Brigitte MANIBAL-PAGES A son retour au Japon, il accepta comme élève personnel un certain Yakumo Koizumi, de son véritable nom Lafcadio Hearn (1850- 1904) écrivain Américain d’origine Irlandaise et Grecque qui, en 1895, publia à Boston le premier livre occidental sur le Judo. LLee JJuuddoo eenn EEuurrooppee Hearn était l’ami du président Théodore Roosevelt et put le . convaincre de la valeur exceptionnelle du Judo. En 1902, le Président invita aux Etats-Unis Yoshiaki Yamashita, l’un des principaux experts du Kodokan. L’intérêt du Président pour le Judo en fit assez rapidement une pratique à la mode dans les meilleurs milieux… D’autres judokas y firent des séjours : notamment Nagaoka, Itsuka, Makino, Kotani, Kuashima, Yoshida, Yamanuchi. Après la seconde guerre mondiale, de nombreux soldats yankees, ayant suivi les cours du Kodokan revinrent enthousiasmés aux Etats- Unis. Maître Kano présenta, en 1889, une première démonstration à Marseille. Kawaishi donna son véritable essor au Judo français. En Grande Bretagne, le judo fut introduit par le maitre Koizimi. Mais, Mikinosuke KAWASHI . jusqu’à la fin de la seconde guerre mondiale, il était l’apanage exclusif d’un petit groupe. A plusieurs reprises, les judokas anglais Le 1 octobre 1935, un Japonais répondant au nom de Mikinosuke reçurent la visite de maîtres japonais, dont Miyaki, YukoTani et Kawaishi arrive en France. -

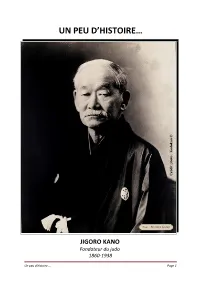

Un Peu D'histoire…

UN PEU D’HISTOIRE… JIGORO KANO Fondateur du judo 1860-1938 Un peu d’histoire … Page 1 Jigoro KANO Né en 1860, décédé en 1938, il a "créé" le Judo en puisant dans le Ju-Jitsu, technique de combat ancestrale, les projections, les immobilisations, les clés de bras, les étranglements et autres techniques utilisées dans notre discipline. Les Dates Importantes : 18/10/1860 : naissance à Mikage (Kobe), de Jigoro, 3ème fils de Jirosaku Mareshiba KANO, intendant naval du Shogunat Tokugawa. 1871 : La famille KANO se fixe à TOKYO. 1877 : Jigoro KANO rentre à l'université impériale de TOKYO. 1878 : Il fonde le Kasei Base Ball Club (le 1er du Japon) Il entre au Tenshin'yo Ryu 1879 : Etudie le Jiu-Jitsu chez le Maître Iso 1881 : Licencié es-lettres - Il entre au Kito Ryu. 1882 : Diplômé en sciences Esthétiques et Morales. Il fonde sa propre école Jiu-Jitsu, le Kodokan, en février. 1884 : Attaché à la Maison Impériale. 1885 : Reçoit le 7ème Rang Impérial. 1886 : Reçoit le 6ème Rang Impérial Il est promu Vice Président au Collège des Nobles. 1888 : Recteur au Collège des Nobles. 1889 - 1891 : En mission en Europe pour le compte de la Maison Impériale. 1891 : Promu conseiller du Ministre de l'Education. 1893 : Directeur de l'Ecole Normale Supérieure puis Secrétaire du Ministre de l'Education. 1895 : Reçoit le 5ème Rang Impérial. 1897 : Crée la société Zoshi-Kai et fonde l’institut Zenyo Seiki, Zenichi, etc. pour la culture des jeunes Il édite la revue « Kokusiai » 1899 : Nommé président du BUTOKUKAI (Centre d'Etude des Arts Martiaux). -

Dr Colin Draycott – a Stalwart of British Judo Interviewed for “Budo” Magazine in 1993 by Yoshiaki Kano, with Japanese- April 2021 To-English Translation by Brian N

Issue No. 48 Dr Colin Draycott – A Stalwart of British Judo Interviewed for “Budo” magazine in 1993 by Yoshiaki Kano, with Japanese- April 2021 to-English translation by Brian N. Watson. Edited by Llŷr Jones Contents Introduction • Dr Colin Draycott – A Stalwart of Thanks to a post on social media by 1984 Olympic Extra-lightweight bronze medal- British Judo – by Yoshiaki Kano (in- list Neil Eckersley, the Kano Society became aware of an interesting article on a terviewer), Brian Watson (translator) stalwart supporter of British judo, Dr Colin Charles Draycott IJF 8th dan. The inter- ̂ and Llyr Jones (editor) view highlights Dr Draycott’s deep technical knowledge of judo as well as his keen • Obituary: Hana Sekine – by John perception of Jigoro Kano-shihan’s psychological theories on the system. The Goodbody reader’s attention is particularly drawn to Colin’s most discerning observations which, for convenience, are highlighted in bold and underlined text. • Hana Sekine: Judo’s Centenarian Passes Away – by Jo Crowley • In Memoriam – Henri Courtine – compiled by Llyr̂ Jones • Points to Ponder – compiled by Brian Watson & Llyr̂ Jones • Judo Collections at the University of Bath. Publisher’s Comments The Kano Society mourn the passing, very late on Friday 8 January 2021, of Hana Sekine (née Koizumi, aged 100). Hana had an incredible heritage and lived a very full and vibrant life, though she had recently fractured her hip. Everyone who came in contact with Hana held her in the greatest regard, and with her passing the last connection to the founding of The Bu- dokwai has been severed. -

Kōdōkan Jūdō's Inauspicious Ninth Kata: the Joshi Goshinhō

REVIEW PAPER Kōdōkan Jūdō’s Inauspicious Ninth Kata: The Joshi goshinhō – “Self-Defense Methods for Women” – Part 3 Authors’ Contribution: Carl De CréeABDE, Llyr C. JonesBD A Study Design B Data Collection International Association of Judo Researchers, United Kingdom C Statistical Analysis D Manuscript Preparation E Funds Collection Source of support: Self-financing Received: 19 April 2011; Accepted: 13 June 2011; Published online: 18 July 2011 Abstract Background The purpose of the present paper is to provide a comprehensive review of Joshi goshinhō [“Self-defense methods for and Study Aim: Women”], the now reclusive ‘ninth’ kata of Kōdōkan jūdō, once part of the standard women’s jūdō curriculum in Japan. Material/Methods: To achieve this, we offer a careful critical analysis of the available literature and rare source material on this kata. Results: Historically, women practiced a less physical jūdō than men, their instruction being chiefly driven by health promo- tion-oriented calisthenics. Joshi goshinhō was created in 1943, following an order by Nangō Jirō, a retired Japanese Navy rear admiral in charge of the Kōdōkan. Joshi goshinhō would meet the increasing demands for more self-defense- oriented jūdō for women. However, jūdō, and joshi goshinhō in particular, also matched popular fascist views of body image in war-time Japan. Joshi goshinhō’s current state of decline is caused by: unavailability of competent teachers, a misconstrued perception that links it to gender discrimination, the sportification of jūdō, concerns about the ef- fectiveness of its techniques, and reminiscences to the jingoist ideologies of Nangō Jirō. Therefore it has become victim to the long-established self-critiqueless and historic revisionist practices of the Kōdōkan leading to a silent exit.