Cascading Style Sheets, Level 2 W3C Proposed Recommendation 24-Mar-1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advancements in Web Typography (Webfonts and WOFF)

Advancements in Web Typography (WebFonts and WOFF) Aaron A. Aliño Graphic Communication Department California Polytechnic State University 2010 Advancements in Web Typography (WebFonts and WOFF) Aaron A. Aliño Graphic Communication Department California Polytechnic State University 2010 Table of Contents Chapter I: Introduction………………………………………………………….…………..2 Chapter II: Literature Review……………………………………………………….………5 Chapter III: Research Methods………………………………………………….…..…....18 Chapter IV: Results………………………………………………………………….……..24 Chapter V: Conclusions……………………………………………………………….…..38 References……………………………………………………………………………...…..41 1 Chapter I: Introduction When it comes to the control one has in designing and creating content for the World Wide Web, typography should be no different. Print designers have had the advantage for a long time over their ability to choose exactly how type is printed, limited only by their imagination and the mechanical limits of setting and printing type. Web designers, on the other hand, have been held back by the inherent hardware and software limitations associated with web design and font selection. What this means is that web designers have not been able to control type exactly the way they want. Web designers have been limited to fonts that can safely be displayed on most computers and web browsers. If web designers wanted to display type with a special font, they had to resort to a workaround that was not always effective. Web designers should have the same absolute control over typography as print designers. Control of web typography has gotten much better compared to the early days of web design, but 2 considering how powerful and robust computers and web browsers are now, it seems unfortunate that control over web typography is so primitive That has changed now. -

Finding, Testing, and Using Web Fonts Laura Franz, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth 1

Finding, Testing, and Using Web Fonts Laura Franz, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth 1 Finding, Testing, and Using Web Fonts Laura Franz, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Where should I get my fonts? There is no wrong or right answer. It depends on your needs. • Ease of use (how much CSS do you need/want to know/use? How easy is the interface?) • Control/ownership (do you or your client want to own the font license?) • Cost • Quality • Availability of specific fonts (do you or your client need a specific font?) • Availability of desktop fonts for mock-ups • Screenshots of how fonts work cross browser Web font providers in alphabetical order (leaving out those with confusing interfaces and pricing plans): Self Host? Host on Desktop fonts Screenshots Pricing Fee Free Trial their for mock-ups of fonts cross Schedule available? server? provided? browser? Fontdeck No Yes No No Pay per font. Example: Din Text Pro Annual Yes (each weight/style charged separate- ly) $12.50/year. (1m page views) Fonts.com Yes, with Yes Yes, with Pro Yes Standard plan (500,000 monthly Monthly Yes Pro Plan Plan page views) is $20/mo. Pro plan is $100/mo. FontSpring Yes No Yes (otf) No Purchase font licenses. A full One Free fonts family (3–14 weights and styles) Time available costs $0–$300. Fee FontSquirrel Yes No Yes (otf) No Free None Free Google Web Fonts Yes Yes Yes No Free None Yes Justanotherfoundry No Yes No No Each family (all weights and styles, Annual Yes 2gb/Month traffic) €19/year myfonts.com Yes No Yes, with Yes Futura (6 weights and styles) 10,000 One Yes higher plan monthly views $133.68. -

Web Type: the Next Big Thing NYC Web Design Meetup July 19, 2010

Web Type: The Next Big Thing NYC Web Design Meetup July 19, 2010 Jaron J. Rubenstein Rubenstein Technology Group http://www.rubensteintech.com/ Overview Technology Licensing Foundries and Distributors Code Results Issues Conclusion References Copyright © 2010, Rubenstein Technology Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Evolution of Web Type Web Fonts – Arial, Times New Roman, etc. – Verdana, Georgia, Tahoma, Trebuchet MS, etc. Scalable Inman Flash Replacement (sIFR) – JavaScript/Flash text replacement – Requires Flash plugin – Limitations for animation, dynamic text, Cufón – Replaces text with VML (MSIE) or SVG (everything else) – Rather slow, complex, has some issues with text selection and screen rendering CSS and @font-face – Method of specifying and downloading fonts – Not “HTML5” , introduced in CSS2 in 1998, standardized in CSS3 – Works with MSIE4+, Firefox 3.5+, Safari 3.1+, Opera 10+ and Chrome 4.0+ – Specification: http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-fonts/#font-resources Copyright © 2010, Rubenstein Technology Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. @font-face Font Formats TrueType (TTF) – Firefox 3.5+ , Opera 10+, Safari 3.1+, Chrome 4.0.249.4+ Embedded OpenType (EOT) – Microsoft Internet Explorer 4+ Web Open Font Format (WOFF) – Firefox 3.6+, Internet Explorer 9+, Chrome 5+ Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) – iPad and iPhone Scalable Vector Graphics, gzipped (SVGZ) – Compressed SVG files (via gzip compression) – iPad only Copyright © 2010, Rubenstein Technology Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Format Browser Compatibility Browser TrueType WOFF EOT SVG SVGZ MSIE 4 - 8 Yes MSIE 9 Soon Yes Firefox 3.5+ Yes Firefox 3.6+ Yes Yes Safari 3.1+ Yes Yes Yes Chrome 4+ Yes Soon Yes Yes Opera 10+ Yes Soon Yes Yes iPhone Yes iPad Yes Yes Source: http://www.fontspring.com/fontface Copyright © 2010, Rubenstein Technology Group, Inc. -

Richard Rutter

Where Web Typography Goes to Next Richard Rutter Sunday, 13 March 2011 apple.com Sunday, 13 March 2011 ÿ Sunday, 13 March 2011 Ultra light Adelle Light Adelle Regular Adelle Bold Adelle Black Adelle Ultra black Adelle Sunday, 13 March 2011 Light Adelle Regular Adelle SemiBold Adelle Bold Adelle ExtraBold Adelle Heavy Adelle Sunday, 13 March 2011 h1 { font-family: “Adelle”, Cambria, Georgia, serif; font-weight: bold; } Sunday, 13 March 2011 h1 { font-family: “Adelle”, Cambria, Georgia, serif; font-weight: 200; } Sunday, 13 March 2011 Values for font-weight property 100 Ultra Light, Extra Light 200 Light, Thin 300 Book 400 Normal, Regular 500 Medium 600 Demi Bold, Semi Bold 700 Bold 800 Black, Extra Bold 900 Ultra Bold, Fat, Heavy Sunday, 13 March 2011 Opera 11 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Firefox 3.6 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Safari 5 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Adelle in FontExplorer X Sunday, 13 March 2011 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Extra condensed Clarendon Condensed Clarendon Regular Clarendon Expanded Clarendon Extra expanded Clarendon Sunday, 13 March 2011 h1 { font-family: “Clarendon”, Georgia, serif; font-stretch: condensed; } Sunday, 13 March 2011 Values for font-stretch property Ultra Condensed Extra Condensed Condensed Semi Condensed Normal Semi Expanded Expanded Extra Expanded Ultra Expanded Sunday, 13 March 2011 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Sunday, 13 March 2011 Font Linking Sunday, 13 March 2011 @font-face { font-family: "Clarendon"; src: url("clarendon-nar-eb.woff"); } Sunday, 13 March 2011 @font-face { font-family: -

VISUAL Quickstart GUIDE CSS3

VISUAL QUICKSTART GUIDE CSS3 SIXTH EDITION JASON CRANFORD TEAGUE Peachpit Press Visual QuickStart Guide CSS3 Sixth Edition Jason Cranford Teague Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com Find us on the Web at www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education Copyright © 2013 by Jason Cranford Teague Project Editor: Nancy Peterson Development Editor: Bob Lindstrom Copyeditors: Liz Merfeld and Darren Meiss Production Editor: Katerina Malone Compositor: David Van Ness Indexer: Jack Lewis Cover Design: RHDG / Riezebos Holzbaur Design Group, Peachpit Press Interior Design: Peachpit Press Logo Design: MINE™ www.minesf.com Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on obtaining permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in preparation of this book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Visual QuickStart Guide is a registered trademark of Peachpit Press, a division of Pearson Education. Other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. -

Richard Rutter

The Future of Web Typography Richard Rutter ÿ Ultra light Museo Slab Light Museo Slab Regular Museo Slab Bold Museo Slab Black Museo Slab Ultra black Museo Slab Ultra light Museo Slab Light Museo Slab Regular Museo Slab Bold Museo Slab Black Museo Slab Ultra black Museo Slab h1 { font-family: “Museo Slab”, Georgia, serif; font-weight: bold; } h1 { font-family: “Museo Slab”, Georgia, serif; font-weight: 200; } Values for font-weight property 100 Ultra Light, Extra Light 200 Light, Thin 300 Book 400 Normal, Regular 500 Medium 600 Demi Bold, Semi Bold 700 Bold 800 Heavy, Black, Extra Bold 900 Ultra Black, Extra Black, Fat, Poster Extra condensed Clarendon Condensed Clarendon Regular Clarendon Expanded Clarendon Extra expanded Clarendon h1 { font-family: “Clarendon”, Georgia, serif; font-stretch: condensed; } Values for font-stretch property Ultra Condensed Extra Condensed Condensed Semi Condensed Normal Semi Expanded Expanded Extra Expanded Ultra Expanded ffi ff fl ffl &i f&i fb fk fí ff fl ffl fi ffi fí http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css3-fonts/ h1 { font-family: Calluna, Georgia, serif; font-variant-ligatures: common-ligatures; } p { font-family: Calluna, Georgia, serif; font-variant-ligatures: no-common-ligatures; } st ip it ck gi fj ap qu OO h1 { font-family: Calluna, Georgia, serif; font-variant-ligatures: common-ligatures additional-ligatures; } !""#$%&&% &'(%)*#&%* Ollivette typewriter h1 { font-family: Ollivette, “American Typewriter”, monospace; font-variant-alternates: stylistic(1); } 0123456789 h1 { font-family: Calluna, Georgia, serif; font-variant-numeric: -

7 R Cweghkaj

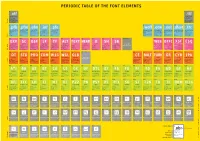

pEriodic taBlE oF the Font ElEmEnts 1 2 .otf .ttf OpenType Font File TrueType Font File PostScript = CFF TrueType (TTF) (TrueType = TTF) Glyphs: x³-Bézier splines Glyphs: x²-Bézier splines adobe (microsoft) microsoft, adobe Mac OS, Windows Flavour Mac OS, Windows 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 .pfb .pfm .afm .inf .pfa .woff .otw .eot .dfont .ttc PostScript Font Binary PostScript Font Metric Adobe Font Metric Information Printer Font ASCII Web Open Font Format OpenType Webfont Embedded OpenType Data Fork Suitcase Format TrueType Collection PostScript Type 1 PostScript Type 1 PostScript Type 1 PostScript Type 1 PostScript Type 1 TrueType, PostScript TrueType, PostScript TrueType, PostScript TrueType/QuickDraw GX TrueType Glyph data Font metric information Metric information (ascii) Font information (ascii) ascii version of PFB Webfont generic Webfont extension Webfont Multiple fonts container adobe adobe adobe adobe adobe van blokland/leming/kew ascender microsoft, ascender apple microsoft, adobe Windows Windows Mac OS, Linux Windows, DOS Linux Firefox Internet Explorer et al Internet Explorer Mac OS X Mac OS, Windows Files 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 – 59 60 61 62 63 Exp sc osF lF tF alt tExt head d sH sB web offc xsF Esq Expert (Set) Small Caps Old Style Figures Lining Figures Tabular Figures Alternates Text Headline Display Supertype Bodytype see OpenType Webfont Office Excellent Screen Font Exhanced Screen Font Typographic features PostScript Type 1 PostScript PostScript PostScript, TrueType PostScript, TrueType PostScript (TrueType) -

Copyrighted Material

Index alt property, 62 • Symbols and AngularJS (Google library) Numerics • Google CDN, accessing with, 177 jQuery, combining with, 179 , (commas), separating tags with, 24 online resources, 178–179 { } (curly braces) overview, 178–179 $ (dollar signs), 118 animate( ) method > (greater-than signs), separating overview, 145 tagswith, 24 properties supported, 146 # (hashtags) transformations, using with, 152 color attribute, using with, 15, 57 Animate.css library, 313–315 hexadecimal color values, using with, 253 animated class, 314 jQuery, using with, 277 Animated Gif tool styles, using with, 15 images, creating, 244 - (hyphens), using with attribute online resources, 243 selectors, 32 test page, creating, 245 + (plus signs), separating tags with, 24 animations “ (quotes), using with spaces, 16 adding with animate( ) method, ~ (tildes), separating tags with, 24 145–146 “30 CSS Best Practices for Beginners” advantages of, 243 (Stansberry), 344 browser support, 11–13 960 Grid System website, 339 colors, 145–146 creating with Animated Gif, 243–245 • A • images, creating, 244 lists, 330–331 Accordion widget, 126–127 online resources, 107, 243, 317–320 :active state selector, 38 overview, 244 AddClass( ) method, 147–148 Stylie generator, 323–325 addClass( ) method, 139 test page, creating, 245 add-ons, 190 transitions, 243–245 Adobe Flash. See Flash API (Application Programming Interface). :after pattern selector,COPYRIGHTED 34 See MATERIAL also Google API AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) browsers targeted, 176 Dojo support, 179 CDN, solving -

@Font-Face the Web Open Font Format (WOFF) Is Supported By

PAGE 1/3 ............................................................................................................................... @font-face BROWSER SUPPORT The Web Open Font Format (WOFF) is supported by Mozilla Firefox 3.6+, Google Chrome 5+, Opera Presto, by Mac OS X Lion's Safari from release 5.1 and is supported by Internet Explorer 9 (Version 4 and higher can use web fonts in Embedded OpenType (EOT) format). WOFF2 is supported on Safari 10 on OS X Sierra, and all actual versions of Chrome, Firefox and Opera. All OpenType features are supported according to this last browser versions, like Kerning (kern), Ligatures (liga/clig), Contextual Alternates (calt), Numerators (numr), Oldstyle Numerals (onum), Proportional Numbers (pnum), Tabular Numbers (tnum), Small Capitals (smcp), Case-Sensitive Forms (case) and finally Slashed Zero (zero). USING WEBFONTS WITH CASCADING STYLE SHEETS (CSS) Upload the font files to your web server. You need the files EOT, WOFF and WOFF2 for each font style you want to use in your site. Use the CSS code example below to address your webfonts. Replace the example font file URL with its appropriate path on your server. @font-face { font-family: 'FontName'; ............................................................................................................................... src: url('/fonts/fontname-webfont.eot'); src: local('‚ò∫'), url('/fonts/fontname-webfont.woff2') format('woff2'), url('/fonts/fontname-webfont.woff') format('woff'); font-weight: normal; font-style: normal; } You can then reference your font family by the name you gave it in CSS font stacks as you would any other font. CONTROLLING KERNING AND LIGATURES VIA CSS You can use the non-standard CSS property text-rendering to control the usage of kerning and ligatures in Firefox (version 3+). -

Richard Rutter

The Future of Web Typography Richard Rutter I’m cofounder of Clearleft, a user experience consultancy in Brighton. I’m an user experience designer by day and a web typography evangelist by night. In fact I’m also that by day now because I’m cofounder of Fontdeck, and webfonts service. ÿ Typography is important because most of the content on the web consists of words. And if those words are to be read, and for that reading experience to be good, then it’s the details that count. I’m going to go through some of the upcoming CSS3 features that provide more control over the details, and later on I’ll do a quick demo of Fontdeck. Ultra light Museo Slab Light Museo Slab Regular Museo Slab Bold Museo Slab Black Museo Slab Ultra black Museo Slab Let’s start with some CSS 1. Font-weight. Here’s regular and bold of Museo Slab Ultra light Museo Slab Light Museo Slab Regular Museo Slab Bold Museo Slab Black Museo Slab Ultra black Museo Slab Not just regular and bold, but also light, ultralight, bold, black, ultrablack. h1 { font-family: “Museo Slab”, Georgia, serif; font-weight: bold; } You’ll be familiar with this: using font-weight with the ‘bold’ keyword. h1 { font-family: “Museo Slab”, Georgia, serif; font-weight: 200; } But to set a weight lighter than regular, or indeed heavier than bold, we need to resort to a numerical scale. Values for font-weight property 100 Ultra Light, Extra Light 200 Light, Thin 300 Book 400 Normal, Regular 500 Medium 600 Demi Bold, Semi Bold 700 Bold 800 Heavy, Black, Extra Bold 900 Ultra Black, Extra Black, Fat, Poster Scale roughly matches to this. -

Unusual Fonts in Web Pages

Unusual Fonts in Web Pages After a lot of Research into, and Testing of, Webfonts, I have revised this substantially. (Thank you, Franklin Einspruch, of the Boston Comics Rountable, for all your feedback. You are like a Wise Tribal Elder.) And, at the risk of telling you stuff you already know, I have attempted to make this as maximally useful as possible. (There’s no point in telling somebody that “Hey, there’s this cool, new stuff you can do”, and then leaving them hanging with abstruse or incomplete instructions, just because “Well, everyone knows that!” A lot of the time, they don’t.) Next, if you are the type of person who likes to eat your dessert first, or rip open presents the second you see them, you can jump to the example page here: http://www.storyspace.org/Alt_Events_Test.asp . This is a tarted-up, alternative version of a Page from a Website that I maintain. It has a number of unusual Fonts on it. I found them online, and they all seemed like they might be really cool. You can judge for yourself whether or not that is true. Perhaps you may even decide that the results are not worth the bother, and stop reading here. When it comes to using fancy Fonts on the Internet, remember the immortal words of blind Master Po, “Choose wisely, Grasshopper.” Downloading A Font The great thing about Downloaded Fonts is that they are different from the usual fonts on your Computer. If you do not want to do all of your lettering by hand, and you’re tired of Arial, Courier, Garamond, Helvetica, etc., you can probably find a font Online that has the look and feel of what you are trying to convey in your Artwork/Comics. -

Get More Free Tips, Tools and Services at Our Web Site: Page 2 Technology Update How to Avoid Runaway IT Projects That Empty Your Wallet

August 2015 Microsoft Releases Emergency Patch for a Dangerous Vulnerability in Windows Inside This Issue… Security researchers from Google’s Project Zero and FireEye have Microsoft Releases Emergency Patch... Page 1 discovered a critical flaw in various versions of Windows, and Microsoft How To Avoid Runaway IT Projects Page 2 has released an emergency out-of-band patch to deal with the situation. Tek Tip Of The Month Page 2 Shinny New Gadget Of The Month Page 2 In a statement of advisory on Monday (July 20), Microsoft informed After Networks Plays The Blame Game Page 3 customers about the issue, warning that the vulnerability could “allow The Niagara Business Owners’ Guide remote code execution if a user opens a specially crafted document or To IT Support Services And Fees Page 4 visits an untrusted webpage that contains embedded OpenType fonts.” Do You Keep Your Server In A Closet? Page 4 They continued, “An attacker could then install programs; view, change, Client Spotlight: Lifetime Vision Centre Page 5 or delete data; or create new accounts with full user rights.” How Great Leaders Inspire Employees Page 5 The B4 Networks Family Page 6 Basically what this means is that if the vulnerability were exploited, you’d Trivia Challenge Page 6 be inadvertently handing operational control of your computer over to a How To Backup Your Smartphone? Page 6 cybercriminal, all by simply opening up an innocent looking document, or just visiting an infected website. The potential issues stemming from that are limitless, especially for businesses storing sensitive data on their machines.