English Medium for the Government Primary Schools of Sindh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Elite Culture by Pakistani Tv Channels ______

PROMOTING ELITE CULTURE BY PAKISTANI TV CHANNELS ___________________________________________________ _____ BY MUNHAM SHEHZAD REGISTRATION # 11020216227 PhD Centre for Media and Communication Studies University of Gujrat Session 2015-18 (Page 1 of 133) PROMOTING ELITE CULTURE BY PAKISTANI TV CHANNELS A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Degree of PhD In Mass Communications & Media By MUNHAM SHEHZAD REGISTRATION # 11020216227 Centre for Media & Communication Studies (Page 2 of 133) University of Gujrat Session 2015-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very thankful to Almighty Allah for giving me strength and the opportunity to complete this research despite my arduous office work, and continuous personal obligations. I am grateful to Dr. Zahid Yousaf, Associate Professor /Chairperson, Centre for Media & Communication Studies, University of Gujrat as my Supervisor for his advice, constructive comments and support. I am thankful to Dr Malik Adnan, Assistant Professor, Department of Media Studies, Islamia University Bahawalpur as my Ex-Supervisor. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Farish Ullah, Dean, Faculty of Arts, whose deep knowledge about Television dramas helped and guided me to complete my study. I profoundly thankful to Dr. Arshad Ali, Mehmood Ahmad, Shamas Suleman, and Ehtesham Ali for extending their help and always pushed me to complete my thesis. I am thankful to my colleagues for their guidance and support in completion of this study. I am very grateful to my beloved Sister, Brothers and In-Laws for -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

Impact of COVID-19 on Reproductive Health and Rights in Sindh

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN SINDH The Collective for Social Science Research was established in 2001 with a small core staff of researchers in the social sciences who have extensive experience conducting multidisciplinary research both in Pakistan and internationally. Areas of research interest include social policy, economics, poverty, gender studies, health, labor, migration, and conflict. The Collective's research, advisory, and consultancy partnerships include local and international academic institutes, government and non-governmental organizations, and international development agencies. Collective for Social Science Research 173-I, Block 2, P.E.C.H.S. Karachi, 75400 PAKISTAN For more than 25 years, the Center for Reproductive Rights has used the power of law to advance reproductive rights as fundamental human rights around the world. We envision a world where every person participates with dignity as an equal member of society, regardless of gender; where every woman is free to decide whether or when to have children and whether to get married; where access to quality reproductive health care is guaranteed; and where every woman can make these decisions free from coercion or discrimination. Center for Reproductive Rights 199 Water Street, 22nd Floor New York, NY 10038 U.S.A. For more information contact Ayesha Khan ([email protected]) or Sara Malkani ([email protected]). IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN SINDH TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 6 I. Legal and Policy Framework 7 II. Methodology 10 III. Findings 11 IV. Recommendations 18 Annex 1. List of Key Informant Interviews 20 Annex 2. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Aamir, A. (2015a, June 27). Interview with Syed Fazl-e-Haider: Fully operational Gwadar Port under Chinese control upsets key regional players. The Balochistan Point. Accessed February 7, 2019, from http://thebalochistanpoint.com/interview-fully-operational-gwadar-port-under- chinese-control-upsets-key-regional-players/ Aamir, A. (2015b, February 7). Pak-China Economic Corridor. Pakistan Today. Aamir, A. (2017, December 31). The Baloch’s concerns. The News International. Aamir, A. (2018a, August 17). ISIS threatens China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. China-US Focus. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https://www.chinausfocus.com/peace-security/isis-threatens- china-pakistan-economic-corridor Aamir, A. (2018b, July 25). Religious violence jeopardises China’s investment in Pakistan. Financial Times. Abbas, Z. (2000, November 17). Pakistan faces brain drain. BBC. Abbas, H. (2007, March 29). Transforming Pakistan’s frontier corps. Terrorism Monitor, 5(6). Abbas, H. (2011, February). Reforming Pakistan’s police and law enforcement infrastructure is it too flawed to fix? (USIP Special Report, No. 266). Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Abbas, N., & Rasmussen, S. E. (2017, November 27). Pakistani law minister quits after weeks of anti-blasphemy protests. The Guardian. Abbasi, N. M. (2009). The EU and Democracy building in Pakistan. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Accessed February 7, 2019, from https:// www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/the-role-of-the-european-union-in-democ racy-building/eu-democracy-building-discussion-paper-29.pdf Abbasi, A. (2017, April 13). CPEC sect without project director, key specialists. The News International. Abbasi, S. K. (2018, May 24). -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Jago Pakistan Wake Up, Pakistan

Members of The Century Foundation International Working Group on Pakistan Pakistan Jago Thomas R. Pickering Working Group Chair Jean-Marie Guéhenno President, Vice Chairman, Hills and Company; former U.S. International Crisis Group Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Nobuaki Tanaka Former Japanese Robert P. Finn Principal Investigator Ambassador to Turkey and Pakistan Non-Resident Fellow, Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination, Princeton University; Ann Wilkens Former Chair, Swedish Pakistan Up, Wake former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Committee for Afghanistan; former Swedish Ambassador to Pakistan and Afghanistan Michael Wahid Hanna Principal Investigator Senior Fellow, The Century Foundation Pakistan Mosharraf Zaidi Principal Investigator Tariq Banuri Professor in the Departments Campaign Director, Alif Ailaan of Economics and City and Metropolitan United States Planning at the University of Utah Steve Coll Dean, Columbia University Graduate Imtiaz Gul Executive Director, Center for School of Journalism Research and Security Studies Cameron Munter Professor of Practice in Ishrat Husain Dean and Director of the International Relations, Pomona College; Institute of Business Administration, Karachi former U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan Jago Asma Jahangir Advocate of the Supreme Barnett Rubin Senior Fellow and Associate Court of Pakistan; Chairperson, Human Director, Afghanistan Pakistan Regional Rights Commission of Pakistan Program, New York University Center on International Cooperation; former Senior Riaz Khohkar Former -

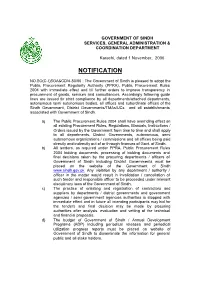

Notification

GOVERNMENT OF SINDH SERVICES, GENERAL ADMINISTRATION & COORDINATION DEPARTMENT Karachi, dated 1 November, 2006 NOTIFICATION NO.SO(C-I)SGA&CD/4-80/06 : The Government of Sindh is pleased to adopt the Public Procurement Regularity Authority (PPRA), Public Procurement Rules 2004 with immediate effect and till further orders to improve transparency in procurement of goods, services and consultancies. Accordingly following guide lines are issued for strict compliance by all departments/attached departments, autonomous semi autonomous bodies, all offices and subordinate offices of the Sindh Government, District Governments/TMAs/UCs and all establishments associated with Government of Sindh. a) The Public Procurement Rules 2004 shall have overriding effect on all existing Procurement Rules, Regulations, Manuals, Instructions / Orders issued by the Government from time to time and shall apply to all departments, District Governments, autonomous, semi autonomous organizations / commissions and all offices being paid directly and indirectly out of or through finances of Govt. of Sindh. b) All tenders, as required under PPRA, Public Procurement Rules 2004 bidding documents, processing of bidding documents and final decisions taken by the procuring departments / officers of Government of Sindh including District Governments must be placed on the website of the Government of Sindh www.sindh.gov.pk Any violation by any department / authority / officer in the matter would result in invalidation / cancellation of such tender and responsible officer to be proceeded under relevant disciplinary laws of the Government of Sindh. c) The practice of enlisting and registration of contractors and suppliers by departments / district governments and government agencies / semi government agencies authorities is stopped with immediate effect and in future all intending participants may bid for the tenders and final decision may be made by procuring authorities after analysis, evaluation and vetting of the technical and financial proposals. -

Paper Template

International Journal of Arts, Culture, Design & Language Kambohwell Publishers Enterprises Vol. 6, Issue 05, PP. 01-10, May 2019 wwww.kwpublisher.com Block Printing in Sindh, AJRAK and other Contemporaray Products Asra Jan, Bhai Khan Shar Abstract— The purpose of the study is to record the oldest printing firmly believe that the shawl draped on the figure of printing technique hand-block printing and preserve its the priest-king is Ajrak and trefoil motif is actually kakar3 1 evergreen product Ajrak which is the traditional textile of pattern but this theory is debatable as no printing evidence has Sindh. To find out the reasons of abandoning this traditional been discovered yet (Bilgrami 1990, p.19). craft and to witness the difference in block printing done before and now. Different towns of Sindh were visited and eleven artisans (Ajrak-maker/block-printer and block-maker) were interviewed and a questionnaire was filled. The results illustrate that they are suffering from many problems but one of the major problem is lack of clean water which is badly affecting their business. It was also observed that traditional Ajrak formats and patterns are disappearing as only one or two patterns are mostly used nowadays. Whereas the machine block printing has somehow also affected the traditional craft. Despite all the problems they are still so passionate about this craft that they are training their children as well but there are certain evidences that Ajrak-making may not remain a family business anymore as it may be transferred to outsiders in future. However, they have also invented different contemporary products using various types of fabrics and patterns in hand-block printing according to the demand of the Figure 1. -

Pakistan: Sindh Devolved Social Services Program

Completion Report Project Number: 34337 Loan Number: 2047/2048 December 2008 Pakistan: Sindh Devolved Social Services Program CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (Pre/PRs) At Appraisal At Program Completion 13 November 2003 19 September 2008 PRe1.00 = $0.0174 $0.0129 $1.00 = PRs57.42 PRs77.70 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADF – Asian Development Fund ASP – annual sector plan CBO – community-based organization DSP – Decentralization Support Program DSSP – Devolved Social Services Program EA – executing agency GRAP – gender reform action plan HMC – hospital management committee LGC – Local Government Commission LGO – local government ordinance LSU – local support unit MDG – Millennium Development Goal MOU – memorandum of understanding MTR – mid-term review NGO – nongovernment organization OCR – ordinary capital resources PCR – program completion report PFC – Provincial Finance Commission PHED – Public Health Engineering Department PLD – provincial line department PRSP – Poverty Reduction Strategy and Program PSU – program support unit SAC – structural adjustment credit SAP – Social Action Program SDR – Special Drawing Rights SDSSP – Sindh Devolved Social Services Program SMC – school management committee TA – Technical assistance TMA – Taluka/town municipal administration TPV – third-party validation USAID – United States Agency for International Development VDA – village development association WSS – water supply and sanitation NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government and its agencies ends on 30 June. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2005 ends on 30 June 2005. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice President X. Zhao, Operations Group 1 Director General J. Miranda, Central and West Asia Department (CWRD) Country Director R. -

Portrayal of Peace in Daily Jang and Daily Times of India (A Comparative Study of Editorials) Dr

Portrayal of Peace in daily Jang and daily Times of India (A Comparative Study Of Editorials) Dr. Sajjad Ahmad Paracha & Afeefa Paracha Abstract This study is based on the work of Fred Dallmayr, ‘Dialogue Among Civilizations; Some Exemplary Voices’ which accomplishes two main things. Firstly, it tells the ways to approach and understand cultures or civilizations. Secondly, it presents practical case studies which show the possibilities and richness of dialogue with different cultures. This study investigates the portrayal of peace by daily ‘Jang’ and ‘Times of India’. It is basically a comparative analysis of portrayal of peace by two Pakistani and Indian elite newspapers. It is a census study conducted by carrying out content analysis of 81 editorials of ‘Jang’ and 75 editorials of ‘Times of India. The findings depict that ‘Jang’ is more positive in portrayal of peace than ‘Times of India’. Keywords: Portrayal of Peace, Culture, Civilizations, Dialogue. 1 Journal of Mass Communication, Vol. 12, May, 2015 Introduction Media of a country is deeply attached with the external affairs and it favors the foreign policy of the country in which it operates during times of crisis and war. In addition to this, the researcher will study the Govt. policies of both countries by analyzing the statements of foreign offices of both countries. The researcher will then compare the interplay between the editorial and govt. policies. (Quail, 1987) According to Mathes, the media enter the conflicts as a third party, where the other two parties are the parties among which conflict exists. If analytically seen, conflict comprises of two parties, one is media which reports on the conflict and the second is the public whom the mass media inform.