TITLE: Notes from Niger AUTHOR: Christopher D'amanda MD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrêt N° 01/10/CCT/ME Du 23 Novembre 2010

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du vingt trois novembre deux mil dix tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-031 du 27 mai 2010 portant code électoral et ses textes modificatifs subséquents ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2010-668/PCSRD du 1er octobre 2010 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le référendum sur la Constitution de la VIIème République ; Vu la requête en date du 8 novembre 2010 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) et les pièces jointes ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 003/PCCT du 8 novembre 2010 de Madame le Président du Conseil Constitutionnel portant désignation d’un Conseiller-Rapporteur ; Ensemble les pièces jointes ; Après audition du Conseiller – rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME Considérant que par lettre n° 190/P/CENI en date du 8 novembre 2010, le Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) a saisi le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition aux fins de valider -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR12228 Implementation Status & Results Niger Transport Sector Program Support Project (P101434) Operation Name: Transport Sector Program Support Project (P101434) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 11 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 26-Nov-2013 Country: Niger Approval FY: 2008 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Sector Investment and Maintenance Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 29-Apr-2008 Original Closing Date 15-Dec-2012 Planned Mid Term Review Date 14-Feb-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 24-Apr-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 10-Sep-2008 Revised Closing Date 15-Dec-2015 Actual Mid Term Review Date 28-Jan-2011 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The project development objectives are to (i) improve the physical access of rural population to markets and services on selected unpaved sections of the national road network, and (ii) strengthen the institutional framework, management and implementation of roadmaintenance in Niger. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost 1. Periodic maintenance and spot rehabilitation of unpaved roads; 24.89 2. Institutional support to main transport sector players 2. Institutional support to the main transport sector players 5.11 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Moderate Moderate Public Disclosure Authorized Implementation Status Overview As of October 31, 2013, the Grant amount for the original project has reached a disbursement rate of about 100 percent. -

Rapport Sur Les Indicateurs De L'eau Et De L'assainissement

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER ----------------------------------------- FRATERNITE – TRAVAIL - PROGRES ------------------------------------------- MINISTERE DE L’HYDRAULIQUE ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ---------------------------------------- COMITE TECHNIQUE PERMANENT DE VALIDATION DES INDICATEURS DE L’EAU ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT RAPPORT SUR LES INDICATEURS DE L’EAU ET L'ASSAINISSEMENT POUR L’ANNEE 2016 Mai 2017 Table des matières LISTE DES SIGLES ET ACRONYMES I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 II. DEFINITIONS ..................................................................................................................... 1 2.1. Définitions de quelques concepts et notions dans le domaine de l’hydraulique Rurale et Urbaine. ................................................................................................................ 1 2.2. Rappel des innovations adoptées en 2011 ................................................................... 2 2.3. Définitions des indicateurs de performance calculés dans le domaine de l’approvisionnement en eau potable ................................................................................... 3 2.4. Définitions des indicateurs de performance calculés dans le domaine de l’assainissement .................................................................................................................... 4 III. LES INDICATEURS DES SOUS – PROGRAMMES DU PROSEHA .......................... 4 IV. CONTRAINTES ET PROBLEMES -

Usaid Peace Through Development Ii

USAID PEACE THROUGH DEVELOPMENT II Quarterly Performance Report: Year 4, Quarter 4 // Reporting Period: July 1 – September 30, 2015 Annual Overview of Activities for Fiscal Year October 2014 – September 2015 October 2015: This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by International Relief and Development Inc. Winners of the contest for best CVE radio drama celebrate at the conclusion of the award ceremony in N’Djamèna, Chad PEACE THROUGH DEVELOPMENT II PEACE THROUGH DEVELOPMENT II (USAID/PDEV II) IS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE SUPPORT OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE THROUGH THE U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Cooperative Agreement Award Number AID-624-A-12-00001 Quarterly Performance Report – Year 4, Quarter 4 Reporting Period: July 1 – September 30, 2015 Submitted to: Noel Bauer, AOTR USAID/West Africa Submitted by: Ora Musu Clemens-Hope, COP November 13, 2015 DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government A festival in Gourcy, highlighting the rakiré tradition brought together different ethnic groups to promote interethnic understanding and peaceful co-existence. Table of Contents ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Suivi Conjoint De La Situation Alimentaire Et Nutritionnelle Dans Les Sites Sentinelles Vulnerables

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Cellule de Coordination du Programme Alimentaire Commission Programme des Nations Système d’Alerte Précoce Mondial Européenne Unies pour l’Enfance SUIVI CONJOINT DE LA SITUATION ALIMENTAIRE ET NUTRITIONNELLE DANS LES SITES SENTINELLES VULNERABLES (Résultats préliminaires 1er passage - Août 2008) CONTEXTE : Dans le cadre du renforcement techniques régionales des structures techniques du de la surveillance de la sécurité alimentaire et Comité National de Prévention et Gestion des crises nutritionnelle au Niger, le SAP (Système d’Alertes alimentaires au Niger (CNPGCA) en janvier Précoces) en collaboration avec les partenaires 2008. Des données sur la sécurité alimentaire des techniques et financiers a mis en place un système de ménages et la situation nutritionnelle des enfants de collecte de données auprès des ménages basé sur des moins de 5 ans seront collectées tous les deux mois sites sentinelles. Au total, 7.300 ménages sont à dans ces communes auprès des mêmes ménages et un enquêter dans 405 villages répartis dans 75 bulletin d’information sur la sécurité alimentaire et communes sélectionnées dans les 147 zones nutritionnelle sera produit. vulnérables identifiées à l’issue des rencontres SIMA SIMA 0 Introduction L’enquête a été conduite entre le 10 et le 30 août 2008. Au total, 7.300 ménages devraient faire l’objet d’un suivi régulier de leur situation alimentaire et nutritionnelle. Pour ce premier passage 6.156 ménages ont été effectivement enquêtés, soit un taux de réalisation de 84,32%. Ces ménages sont répartis -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

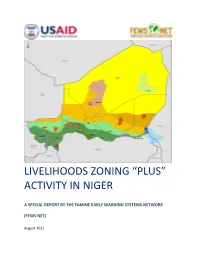

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOROFFMClAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized ReportNo. 7739 PROJECT COMPLETIONREPORT Public Disclosure Authorized NIGER FEEDER ROADS PROJECT (CREDIT886-NIR) APRIL 28, 1989 Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized InfrastructureDivision V This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in theperformance of their offcial duties. Its contents may nototherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. FOR OncALuSONLY THEWORLD BANK Washington.D.C. 20433 U.S.A. Olc d Of cm.gnttal Opweat EVbatuin April 28, 1989 MEMORANDUMTO THE EXECUTIVEDIRECTOPS AND THE PRESIDENT SUBJECT: Project Completion Report on Niger Feeder Roads Project (Credit 886-NIR) Attached, for information, is a copy of a report entitled "Project Completion Report on Niger Feeder Roads Project (Credit 886-NIR)" prepared by the Africa Regional Office. Under the modified system for project performance auditing, further evaluation of this project by the Operations Evaluation Department has not been made. Attachment Thisdocument has a restricteddistribution and may be usedby recipientsonly In the performance of their officialduties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank autborintion. FOR OFMCIL USE ONLY NIGER FEEDER ROADSPROJECT (CREDIT 886-NIR) PROJECT COMPLETIONREPORT Table of Contents Pare No. Preface,................................ Basic Data Sheet .... ..... ii EvaluationSummAnlry ........... .............................. v I. IN RDnTON... .................................1 -

Les Ressources Forestières Naturelles Et Les Plantations Forestières Au Niger

COMMISSION EUROPEENNE DIRECTION-GENERALE VIII DEVELOPPEMENT Collecte et analyse de données pour l’aménagement durable des forêts - joindre les efforts nationaux et internationaux Programme de partenariat CE-FAO (1998-2002) Ligne budgétaire forêt tropicale B7-6201/97-15/VIII/FOR PROJET GCP/INT/679/EC Les ressources forestières naturelles et les plantations forestières au Niger M. Laoualy Ada et Dr Ali Mahamane Août 1999 Ce rapport constitue un des résultats du Programme de partenariat CE-FAO (1998-2002) - GCP/INT/679/EC Collecte et analyse de données pour l’aménagement durable des forêts - joindre les efforts nationaux et internationaux. Les points de vue exprimés sont ceux des auteurs et ne peuvent être attribués ni à la CE, ni à la FAO. Le document est présenté dans une édition simple, pour un unique souci de style et de clarté. Table des matières : Liste des tableaux ..................................................................................................................... 4 Sigles et abréviations................................................................................................................ 6 Remerciements ......................................................................................................................... 7 Résumé ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. -

BROCHURE Dainformation SUR LA Décentralisation AU NIGER

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 Imprimerie ALBARKA - Niamey-NIGER Tél. +227 20 72 33 17/38 - 105 - REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 - 1 - - 2 - SOMMAIRE Liste des sigles .......................................................................................................... 4 Avant propos ............................................................................................................. 5 Première partie : Généralités sur la Décentralisation au Niger ......................................................... 7 Deuxième partie : Des élections municipales et régionales ............................................................. 21 Troisième partie : A la découverte de la Commune ......................................................................... 25 Quatrième partie : A la découverte de la Région .............................................................................. 53 Cinquième partie : Ressources et autonomie de gestion des collectivités ........................................ 65 Sixième partie : Stratégies et outils -

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique Au Niger»

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique au Niger» DIFEB, le 16 Août 2019 SOMMAIRE CEV Plan de déploiement Détails Zone 1 Détails Zone 2 Avantages/Limites CEV Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote CEV: Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote Notion apparue avec l’introduction de la Biométrie dans le système électoral nigérien. ▪ Avec l’utilisation de matériels sensible (fragile et lourd), difficile de faire de maison en maison pour un recensement, C’est l’emplacement physique où se rendront les populations pour leur inscription sur la Liste Electorale Biométrique (LEB) dans une localité donnée. Pour ne pas désorienter les gens, le CEV servira aussi de lieu de vote pour les élections à venir. Ainsi, le CEV contiendra un ou plusieurs bureaux de vote selon le nombre de personnes enrôlées dans le centre et conformément aux dispositions de création de bureaux de vote (Art 79 code électoral) COLLECTE DES INFORMATIONS SUR LES CEV Création d’une fiche d’identification de CEV; Formation des acteurs locaux (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil) pour le remplissage de la fiche; Remplissage des fiches dans les communes (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil et 3 personnes ressources); Centralisation et traitement des fiches par commune; Validation des CEV avec les acteurs locaux (Traitement des erreurs sur place) Liste définitive par commune NOMBRE DE CEV PAR REGION Région Nombre de CEV AGADEZ 765 TAHOUA 3372 DOSSO 2398 TILLABERY 3742 18 400 DIFFA 912 MARADI 3241 ZINDER 3788 NIAMEY 182 ETRANGER 247 TOTAL 18 647 Plan de Déploiement Plan de Déploiement couvrir tous les 18 647 CEV : Sur une superficie de 1 267 000 km2 Avec une population électorale attendue de 9 751 462 Et 3 500 kits (3000 kits fixes et 500 tablettes) ❖ KIT = Valise d’enrôlement constitués de plusieurs composants (PC ou Tablette, lecteur d’empreintes digitales, appareil photo, capteur de signature, scanner, etc…) Le pays est divisé en 2 zones d’intervention (4 régions chacune) et chaque région en 5 aires.